Peaches and post-apocalypses

No. 154

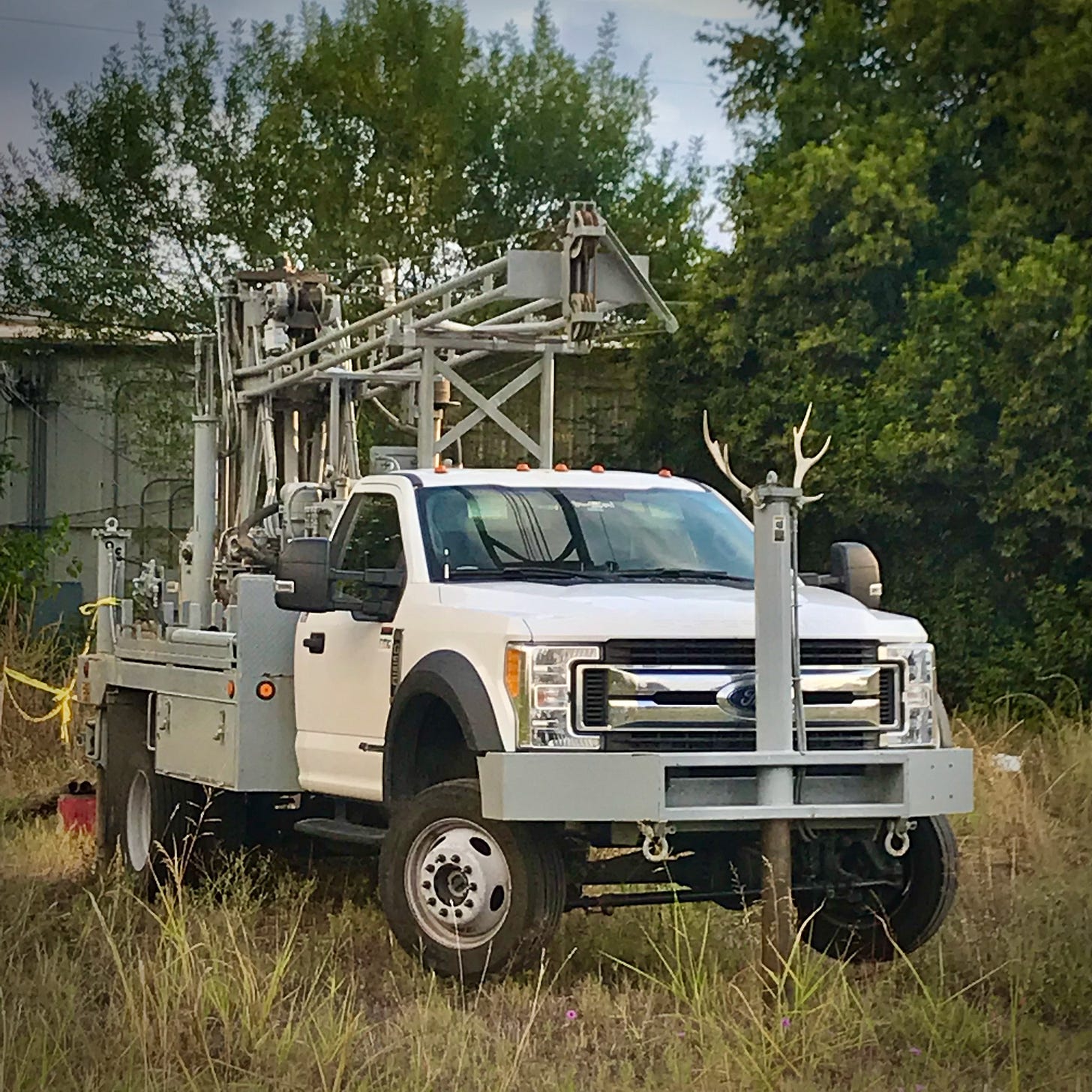

The day before we went to see the new Mad Max movie, I saw a road warrior truck on my morning run. I thought it was one I’d seen before, a few years ago, the way recurring encounters in the liminal city can be spread out across expanses of time. This one was a big white Ford pickup, a dualie, with soil boring machinery in the bed, built-in chocks to stabilize it on the ground it is drilling, and a massive longhorn skull wired to the grill. A 21st-century wagon adorned with the severed head of an animal whose meat could sustain a small band of humans through a lean season.

I didn’t take a picture, thinking I already had one of the same truck, but when I went and found the old photo, it was a different one, the one pictured above with a pair of deer antlers crowning the lift instead of a skull on the grill. Teaching me that these tribal adornments of the advance scouts of the Anthropocene—the crews that drill down to find the bedrock beneath “empty” fields full of wild plants, so they can be bulldozed and covered with the concrete foundations of new buildings—are a common practice.

The antlered truck I saw during Covid was probing the ground of a deserted traffic island, one in which a pocket forest had grown around the abandoned basketball court of some long-forgotten institution. It was a place where I once saw a pair of red-shouldered hawks mating on a low hackberry branch, somehow finding a cocoon of privacy in the midst of the midday traffic. This spring it has finally been razed to make room for some hideous new office complex, the ancient pecans that grew there packed up like the potted plants of the gods and transplanted to some other place.

Last week’s truck was across the street from that spot, at the base of the berm where the onramp used to be, taking borings in a spot where I have seen the plans for the more horrifying bit of infrastructure that’s on the boards—a new front in the State of Texas’ 200-year war against nature. The truck and its crew were there (I presume) to map out the path of what’s coming: a giant drainage tunnel to carry all the effluent of Interstate 35 as it passes through downtown Austin and dump it in the Colorado River, with no treatment other than passage through a big mesh designed to catch large objects, right at what was once a low-water crossing of the Camino Real de los Tejas and is now where Highway 183 crosses the river. Basically right beneath the spot pictured here:

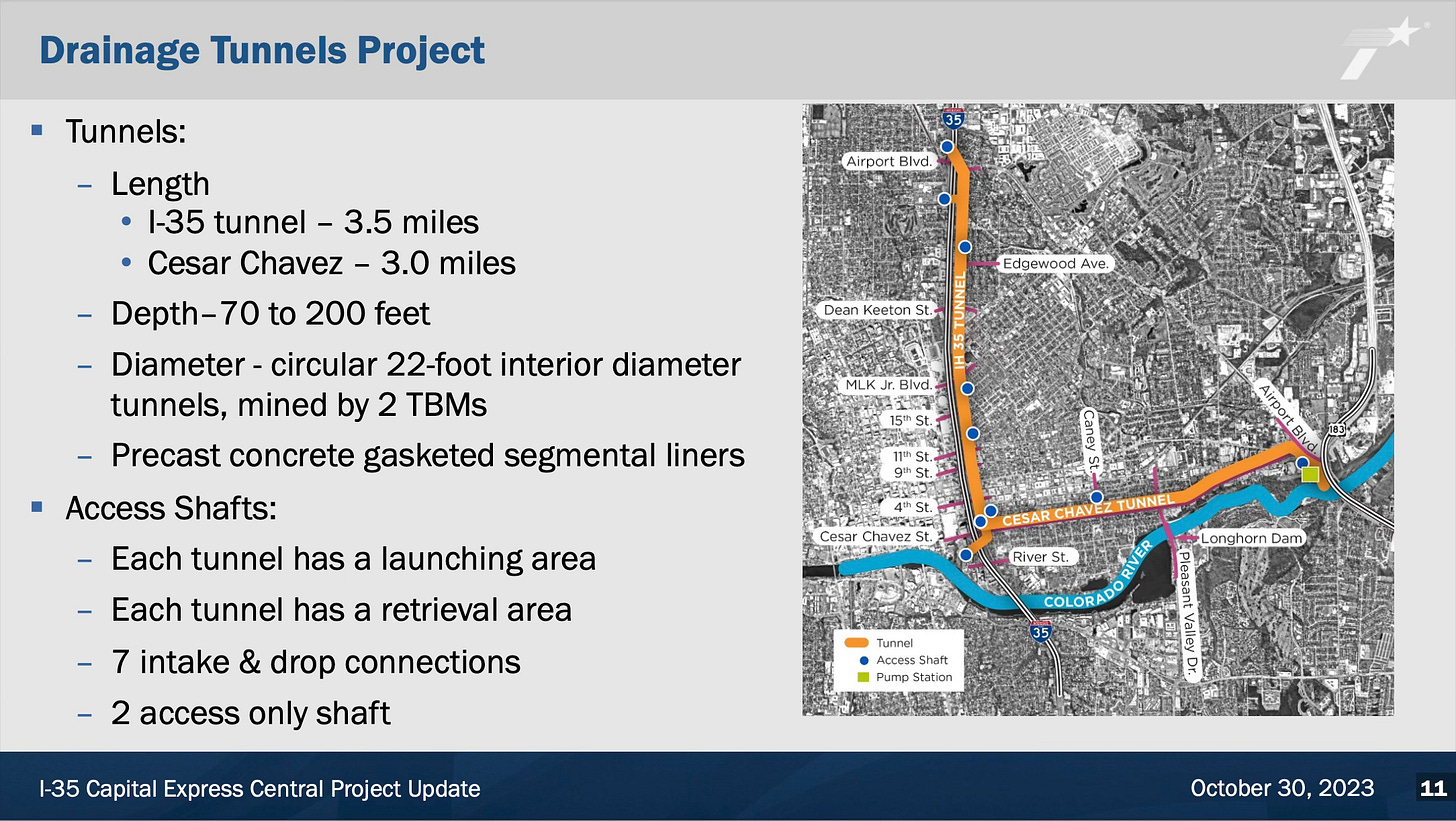

I attended a briefing on the plans last fall, and maybe it’s because I have been in such shock at the obliviousness of the plan to its ecological consequences that it’s taken me so long to write about it. We were busy over the winter with other, more immediate fights over riverfront developments with accelerated permitting calendars. We heard the pitch in October, at the offices of PODER, the East Austin environmental justice nonprofit I do some volunteer work with. The presenters were a huge group of staffers from the Texas Department of Transportation, which conceived the project, and some folks from the City of Austin Watershed Department, gathered at the request of our State Representative. TxDot had just finalized updated plans for the expansion of I-35 as it runs through Austin, from north of the university to the dammed up downtown section of the river (now named Lady Bird Lake) along the path of East Avenue, which was also the Jim Crow-era line of segregation under Austin’s 1928 zoning ordinance.

The proposal has some good things—most notably, tearing down the upper decks that reinforce that segregationist dividing line with a wall of concrete—but mostly, it focuses on making it bigger instead of better, passing on the idea of burying it completely and turning the ground level back into a park. The project will swallow up 54 acres of urban land and make $4.5 billion in “improvements” to increase the road’s carrying capacity. Which raises, for the engineers, the question of where all the water will go. The plan they settled on: collect all the water they can in and around the 45 blocks north of the river, channel it into a gigantic tunnel to be buried 100 feet under East Cesar Chavez Boulevard, and carry it two miles east to a new pumping station to be built on the berm that once carried cars up to the old Montopolis Bridge, run it through that mesh filter to catch large debris, and dump it otherwise untreated into the stretch of the Colorado that is the cleanest urban river in Texas.

The story is still playing out. The City has been working with TxDot on a collaborative plan to move the water to a separate containment where it can be treated to a point where it meets Austin’s water quality standards, perhaps in connection with one of the new riverfront projects we were negotiating with in parallel, but there are no guarantees that will happen. There is also pending litigation regarding the I-35 expansion plans generally, ongoing City efforts to cover it in parts through a “cap and stitch” program, and increasingly organized public opposition. But you could see the resignation on the face of the public servants, their ability to think creatively collared by bureaucratic parameters, limited budgets, and politics. The water has to go somewhere, and making room for more vehicular traffic is the state’s primary concern. Onward, as the old headshop mascot said, through the fog, and into an ever grimmer future.

In the movie we saw last weekend, Furiosa, there was almost no water to be found, but there were lots of men in trucks with savage adornments. A reminder, perhaps, that those go together. I had hoped this fifth Mad Max movie would provide a vision of the “Green Place of Many Mothers”—the more utopian future the last one promised but never delivered. And it did, but (spoiler alert) only a glimpse. The movie opens with the title character as a young girl, picking peaches with a friend from the edge of their secret solarpunk settlement, only to be kidnapped by marauding bikers, like some post-apocalyptic Persephone. The pit that goes with her in her pocket is the only redemptive thing in the two long hours that follow, and the filmmakers try to deploy that seed as the bullet in Chekhov’s gun at the end, only to misfire.

Back home on Sunday, we found our own peach tree had fully fruited. We got the tree as a wedding present from our dear friends Rob and Ren, and planted it next to the grotto we made from all the trash that had been dumped on this brownfield lot before we cleaned it up and made it our homesite. It bore fruit the first year, and every one of the eleven years since. This year we fertilized it with compost Agustina made that looks like some kind of dirty ambrosia, and that, together with the abundant spring rains and the maturity of the tree, resulted in the most prodigious crop ever. Maybe that was the real ending we were looking for.

Monday, Memorial Day, felt like a day of remembrance for lost nature instead of Civil War dead, perhaps due to the movie and the truck. Until, that afternoon, I found the peach tree covered in butterflies—question marks and hackberry emperors, all pigging out on the sweet fruit. You take the redemptive moments where you can get them. And sometimes they make you imagine a more likely version of what the future could really look like, if our society of road warriors and V8 interceptors really did collapse and let nature take back over.

Further reading

I’ve been shooting a lot of film this spring, including a lot of low-light tungsten film, often on an old macro lens, and the results are often pleasing—in part for the way they reveal the beauty of nature at a scale we rarely see, and for the way the analog process mirrors the world with more feeling than digital shots can ever manage. The tungsten lends the green foliage a strong blue back-hue, which amps up the effect. Here’s a favorite from the rolls that just came in, of a skipper on horsemint, one of our later-blooming spring natives:

For a deep dive on I-35, this piece by KUT transportation reporter Nathan Bernier is a great place to start.

For more on the social and political issues raised by such projects, the May issue of The Architect’s Newspaper has a great piece by Anjulie Rao on Megan Kimble’s new book City Limits: Infrastructure, Inequality, and the Future of America’s Highways. The article also has some amazing Ballardian photography by Leonid Furmansky.

For more on the economic consequences of our damage to the planetary environment, the NYT had a remarkable piece about how my home state of Iowa—long considered one of the most predictable climate regions in the U.S.—has developed such volatile weather that property and casualty insurers are rapidly withdrawing from the market.

And on the subject of George Miller’s Furiosa, CNN had a provocative and cogent op-ed by Noah Berlansky on how the movie hits the nail on the head by connecting climate crisis to patriarchy and socio-economic hierarchy.

Congratulations to my amazing son Hugo Nakashima-Brown, a RISD painting grad who just got a second diploma this weekend from Boston’s North Bennet Street School for his studies in furniture making and design. He’s now headed off for a year of fellowships, but we got to see him and some of his latest work before he goes:

Over the next couple of weeks, I’m hoping to put together the first print edition of this newsletter, which I’ll be mailing out to folks who preorder my forthcoming book based on same material, A Natural History of Empty Lots: Field Notes from Urban Edgelands, Back Alleys, and Other Wild Places. If you’re interested in getting that, please email me at chris@christopherbrown.com with your snail mail address and preorder confirmation.

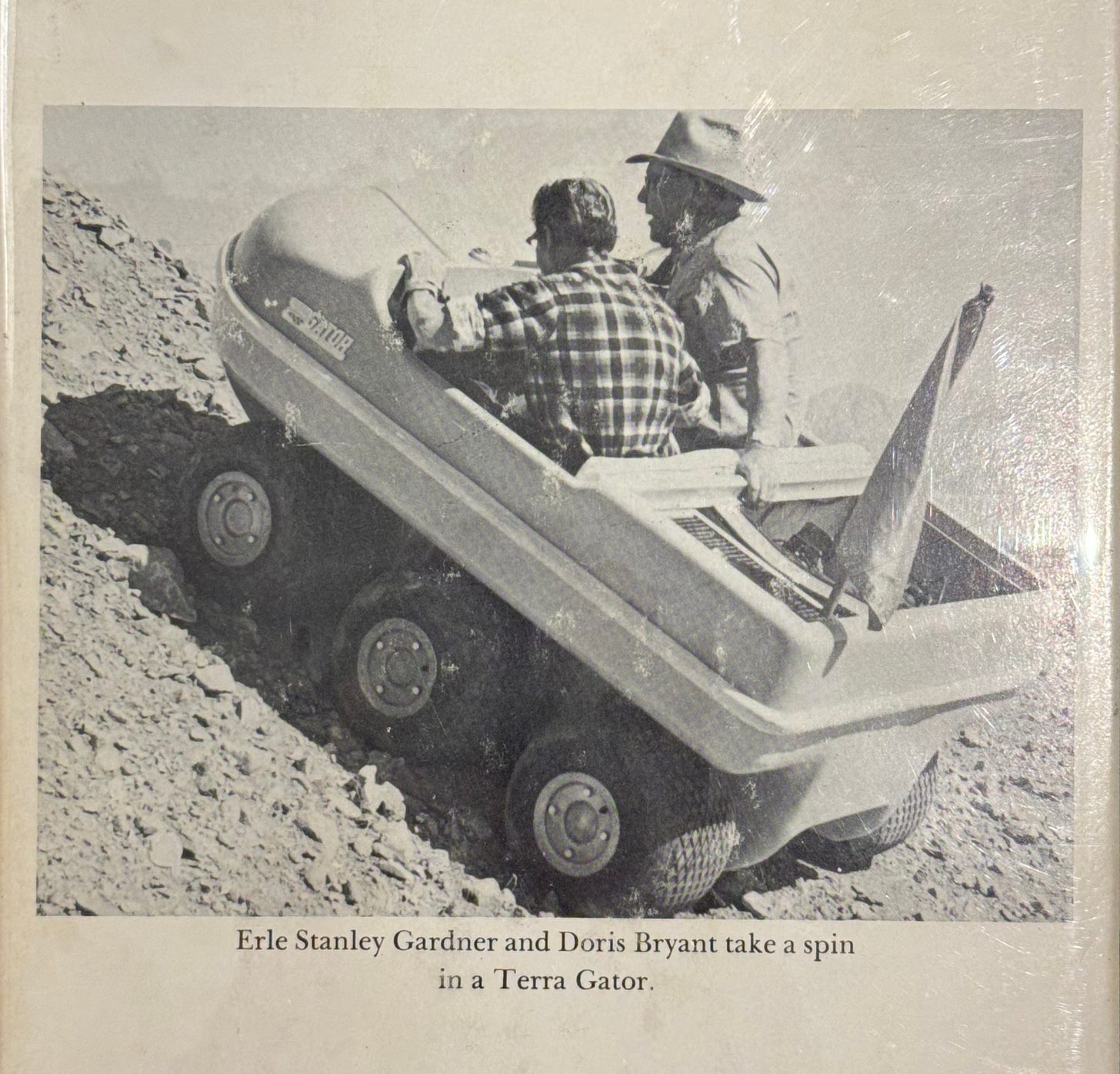

Lastly, while we were in Boston, Hugo and I did some used bookstore trawling, where I came upon one of the weirdest nature books ever: “The Desert is Yours,” a memoir by Perry Mason creator Erle Stanley Gardner about his adventures hunting for lost mines and rare gems, and tearing up the wastelands in his own version of a road warrior vehicle—as featured in this epic author jacket photo:

Welcome June, and have a beautiful week.

Your tungsten pix are indeed beautiful, Chris, and your essay on our future prospects is razor sharp as always. The blue effect in your photos makes me think of the pthalo blue paint I'm addicted to using. There's a property there that plays with light in ways that I don't understand but cannot get enough of. I have to force myself to use other blues.

I grew up in Fort Worth, but have lived on the west coast since my twenties. I have often thought what a fate it would have been to practice environmental law in my home state. I burned out doing so here in Oregon, which at least is blue-green on its face ... I imagine I would have imploded a decade ago dealing with my type of work, if done in Texas. Out west here, at least the public officials, and usually the governors, are somewhat responsive to green pressure. And the judges of the Ninth Circuit tend to enforce process against the agencies. All that to say, I know what you're up against, and thank you for sticking with it. This freeway and tunnel project looks like a complete boondoggle, with the added challenge that it's likely bringing in ... zillions? ... via highway funds.

Loved the horsemint and the cool film. I'm not familiar with it, but it looks a bit like bee balm -- related, I wonder?

Oh! And I finished Rule of Capture last weekend. What a rip-roaring tale! I stayed up late a few too many nights in a row reading it. Feels prescient. Hopefully it's totally off-base in the way I hope Mad Max is totally off-base. Did you see that meme last week: "Mad Max, but as the film progresses, you find out the world outside Australia has stayed pretty normal." Imagine the same for the Republic of Texas.