Nest-building at the End of the World

No. 173

When I got back from Phoenix the Saturday after the Inauguration, I found my car on the top deck of the parking lot and got the idea to turn on the Merlin BirdID app and see if it could hear anything against the jet engine and car traffic noise of the terminal. I only recently started playing with the tool, one of those machine-based nature mediators of the natural world I am highly wary of. I was turned on to it by a friend and found it a useful way to train oneself for deeper listening—learning to hear the birds you would otherwise miss, like the lone bluebird I spotted the other day in a hackberry behind the County Housing Authority’s staging yard across the street, after seeing its call reported among the usual crowd of cardinals, warblers and wrens.

To my surprise, when I turned on the app there atop the airport garage, it blew up with several commonplace birds. I listened with my own ears, heard and placed some of the songs, and went to look. The spot was right over the edge of the deck, where a few landscaper trees get by in the narrow median between the garage and the terminal access road. The canopy of the trees was right at the level of the open rooftop on which I stood. At the top of the central tree was a lone mockingbird, who seemed to be mocking me. But I heard other birds nearby, and in each tree were a dozen or so nests—a density far greater than one normally sees. Each nest was made of a mix of natural and anthropogenic materials, including tangles of synthetic strings in bright yellows, oranges, and pinks, fragments of plastic wrap, and bits of plastic shopping bags. The cardinals around our home do the same thing, with packaging materials harvested from the light industrial sites along our street and the food wrappers and receipts the workers toss from their cars on break. But this was a more intense level of adaptation, to a more intensely industrial location.

There’s a lot of green space around the airport, especially at the outer edges. Onion Creek, an important tributary of the Colorado River, runs through the southeastern corner, and there’s an old cemetery right at the northwest corner. The Colorado River itself, which has largely managed to maintain its wild green character down in the channel despite a history of industrial activity around it, is right across the highway to the north. Given all the interstitial green space and pocket woodlands within a short flight, one wonders why so many songbirds would crowd themselves into the handful of trees at the terminal. Maybe it’s the absence of feral cats, tree-climbing snakes, and other predators.

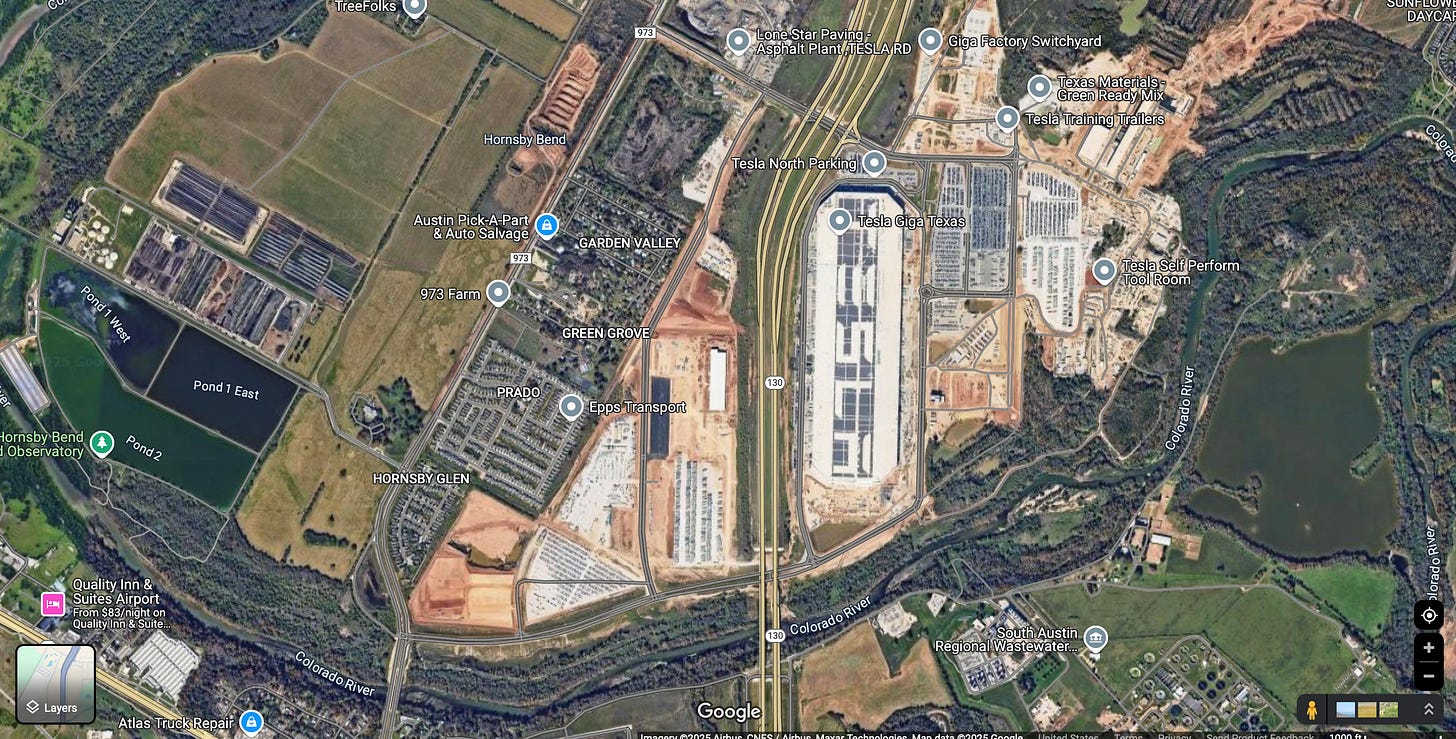

Looking at the online satellite map to identify the bits of habitat around the airfield, I also saw, in what is marked as a very current 2025 image, just how rapidly the Tesla factory on the north bank of the river catacorner from the airport has grown—and how the CEO’s public promise to turn the riparian portion of the site into an “ecological paradise” looks to have been largely forgotten in the urge to expand the use of the site, with the new cathode plant next to the car factory and a half-dozen parking lots bigger than the residential neighborhoods across the road. The project began in the summer of 2020, and the core 10-million square-foot factory building—the second biggest building by volume in the world, after the Boeing airplane factory in Everett, Washington—went up so fast that you couldn’t help but be astonished by the quantity of capital and the intensity of entrepreneurial will it evidenced. And by how compliant all of our local elected officials and bureaucrats were with the program, bought in to a simplistic Chamber of Commerce narrative. I led some early environmental negotiations with the company, heard some stories about what it was like to work there, and got a sense of how terrified many of the executives I interacted with were of their mercurial boss.

The factory is near one of the best birding spots in Texas, Hornsby Bend, which was made from the riparian woods around a municipal wastewater facility (shown on the left side of the above Google Maps image, with the Tesla factory on the right). That site also hosts the city’s Center for Environmental Research, run by the geographer and ecologist Kevin Anderson, a certified expert in urban nature and ecology who conducts an outstanding lecture series every season on the subject. And all of the fertile alluvial land around that bend in the river was farmed by the first family of Anglo settlers in this area, making its 21st century re-colonization by the richest man in the world—the one who wants to apply the same power to colonize Mars—more obviously fit into a deeper historical narrative.

The two contemporary uses of Hornsby’s Bend express two divergent variants of Anthropocene futures—one where the commons is used to clean the wastewater generated by the community and also provide habitat for other species; the other a hyper-libertarian Heinlein plot where the accumulation of almost unimaginable amounts of wealth in the hands of a single human works to accelerate our rampaging technological dominion by making it atmospherically cleaner and putatively sustainable. I wonder whether these dipoles might be reconciled, but then I think about which one draws more human attention and enthusiasm. Tree ducks versus Cybertrucks.

When I got home that Saturday afternoon to our place, a couple miles upriver as the egret flies, I found that a pair of great blue herons have made a nest in one of the tall cottonwoods along the river behind us. I noticed because I heard the skronk of one of them coming in, and looked to see it alighting with the gangly pterosaur anatomy characteristic of those big birds. When I noticed the motion in the nest a little later, walking across the patio from our bedroom to our living room, I saw one of the pair tending to its new brood. Pretty groovy.

There’s a big sycamore at the other end of our street, behind the ruins of the old warehouse that housed the underground club known as the Broken Neck (so called because they built a concrete skate ramp inside the club, the base of which is still there years after the building was demolished), that has six nests of great blues in it. I first noticed the rookery paddling the river in February of 2020, right before lockdown began. Back then it was better hidden, at least from the street. I wrote about it here a couple of times, and devoted a subchapter to it in the book. One of those remarkable examples of wild fauna resiliently making home from the marginal slices of habitat we leave them. Where the more you wonder why they picked that urbanized spot, on an island cluttered with the trash that accumulates below a dam, the more you get to thinking maybe that’s all we’ve left for them.

In the book, I note how the field guides say that in wilderness areas great blue heron rookeries can number as many as 500 nests. As I see our backyard neighbors grow their range into this slice of riparian woods behind the old industrial sites and homesteads of far East Austin, I wonder how many this little stretch of wild urban river could support.

The twentieth century factories above those woods are mostly graffiti-covered ruins now. The forces of so-called progress keep telegraphing their upcoming development as new urbanist wonderlands, but there’s some kind of entropic power at work that seems to slow if not prevent that. Giga Texas itself is on the site of an old Martin Marietta gravel pit that outlasted the economic viability of its former use, and it’s not hard to imagine the time when the shiny new complex there will have taken the same course—abruptly abandoned when fortunes turn, and rapidly rewilded by the other life that lives in and around its margins.

Some days it’s easier to imagine the other ending. But the final act, where nature restores the balance we fail to maintain, seems to have been written long ago. We dream it out loud in our end of the world movies, which pretend to be warnings but read more like yearnings. If we play the long game well, we might even be able to conjure a future where we get to live in an authentically green world, without having to give up the gifts of the gods that let us burn and build our way to this dangerous juncture.

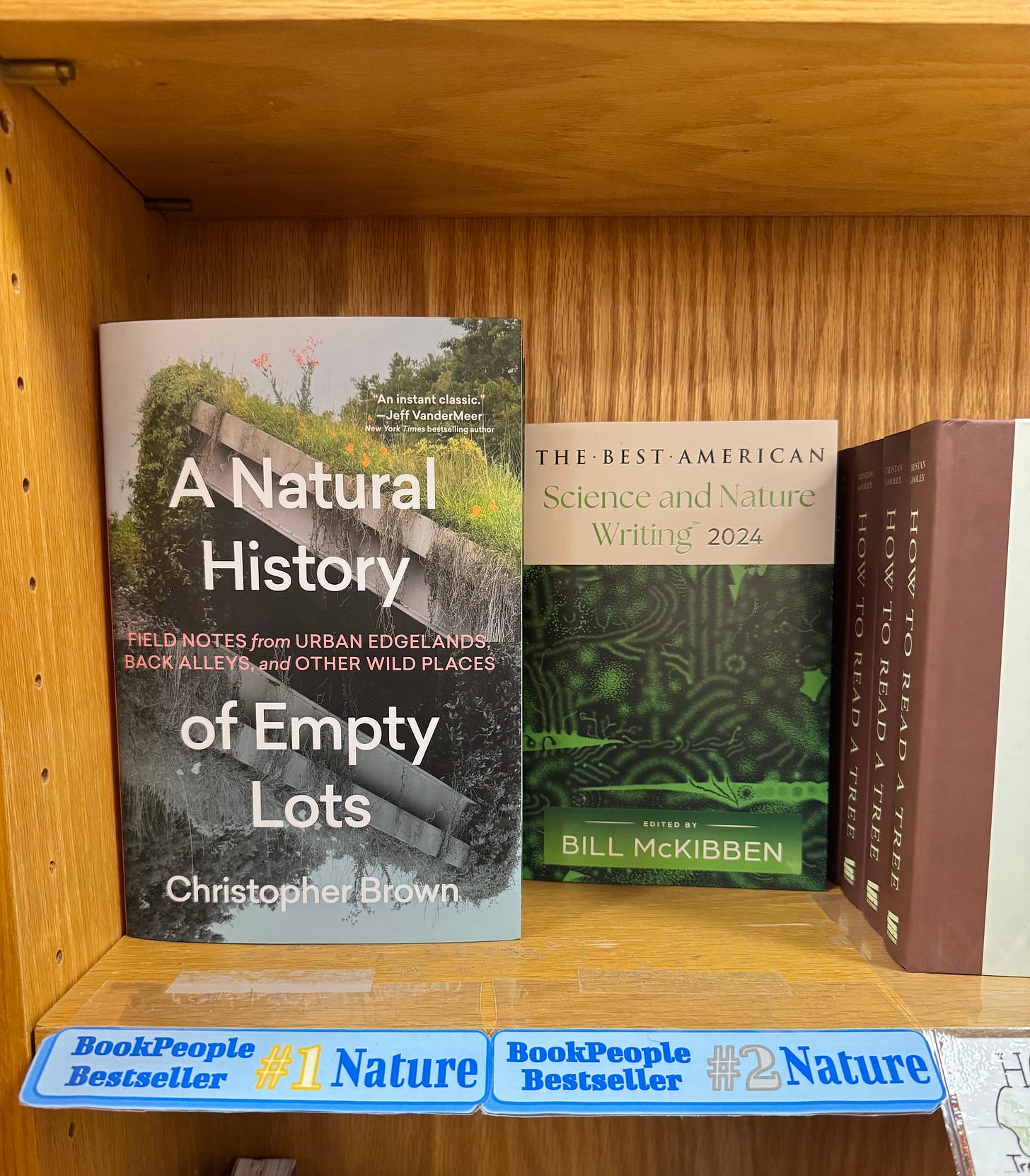

Book News and Further Reading

Thanks to all of you who have helped the launch of A Natural History of Empty Lots over the past several months prove so successful. The word of mouth has been tremendously helpful, as has the support of so many librarians and booksellers. The book has gone to a third printing, the UK release last month almost immediately sold out (more on the way), and a paperback edition is planned for the fall of 2025. If you haven’t gotten your copy yet, my least favorite online bookseller has a limited time 34% discount this weekend on the hardcover edition.

In connection with the UK release, I was delighted to be able to contribute some field notes from January in Texas to The Clearing, the online nature writing project of Dorset-based independent natural history publisher Little Toller Books.

I also had the opportunity to talk about the book with the wildlife photographer Fiona MacKay for her Nurtured by Nature podcast, which is now up on her site and in all the podcast feeds. It was a lovely conversation.

You can’t go skate at the Broken Neck anymore, but you can get a flavor of it in this awesome documentary short from Ashley Sullivan streaming for free on YouTube:

If you want to attract your own great blue heron nest, Cornell’s bird nerds have the platform plans for you right here. They also have that Merlin BirdID app I mentioned earlier.

I loved this January NYT op-ed from Margaret Renkl, “Let’s Hear it for the Coyote in the Produce Aisle,” about urban nature and adaptation. I also appreciated her more recent and more political op-ed about alternative strategies of resistance to what’s going on in Washington.

Patrick Redford has a great piece up at Defector, a cultural Rorschach from last Sunday’s Super Bowl ads that is funny and incisive.

I had a blast at Tuesday’s launch at Alienated Majesty books of the new novel from my friend Austin author Fernando Flores, Brother Brontë. I did not get to ask him what are the three rivers of Three Rivers, Texas, the real town where his fictional dystopia is set, but I loved hearing Fernando read to the standing room only crowd, and I’m excited to dig into the book.

As the news continued to play out like one of those comic book plots in which the super-villains take over the government, an old post of the above image from Giant Super-Team Family No. 8 (1976) showed up in my feed a week or two after the inauguration. I remember buying this comic in a bargain bin a decade ago, and being amused at the insane plot, in which Kissinger really is lost in the Bermuda Triangle, and President Ford dispatches the Challengers of the Unknown to rescue him. I may have to go dig that issue out of the boxes, and see if it has the directions back to Earth-Prime.

Have a safe week, and don’t let the bastards get under your skin.

Gorgeous and thank you: But the final act, where nature restores the balance we fail to maintain, seems to have been written long ago. We dream it out loud in our end of the world movies, which pretend to be warnings but read more like yearnings. If we play the long game well, we might even be able to conjure a future where we get to live in an authentically green world, without having to give up the gifts of the gods that let us burn and build our way to this dangerous juncture.

thank you, once again. i can't help but see those clusters in every tree being the future human adaptations to the coming destruction, challenging us to repurpose creatively for our survival