Owls, Fools and Whorls on Film

No. 176

At 1:25 a.m. on All Fool’s Day, I was awakened by screams in the woods. Our bedroom door opens directly to the outside, on a small patio facing the wooded floodplain of the river, and when the action is close it’s hard not to hear it. It sounded like flying monkeys—abrupt laughs in escalating high-pitched tones, mixed in with the occasional long slow hoooo. Sounds nothing like what the guidebooks and online databases tell you to expect from that species. Maybe they are learning a new language, living in the sonic landscape of the city.

I’ve heard barred owls hooking up before. One morning in the summer of 2023, up early working in the trailer before sunup, I heard similar sounds. When I went out to investigate, I could tell the sound was coming not from the woods behind the fences, but from the streets outside them. They were in a gnarled but mature sidewalk tree, taking advantage of the darkness of this double dead-end where human lovers often park, maybe a hundred feet from the entrance to the tollway onramp. They noticed my eavesdropping, and finally revealed themselves to me as they flew together across the street to a white sycamore by the back gate of the door factory. I tried to call to them, but they weren’t having it.

I recorded Tuesday’s pair on my phone. On playback they seem more distant than they were, especially next to the sounds of me fumbling in the dark. In fact they were there in our yard, as close as my wife and daughter were to me in that moment. The only audible urban sounds were a few cars and trucks rumbling their way over the bridges in the background. Every time I hear one of those big owls nearby, it’s an affirming reminder that wildness can persist in the margins of our rampaging sprawl. Even better when you hear two of them have found each other amidst this damaged habitat, and are making more.

Signs of spring coming up in the ruins are all around us right now, providing a nice counterbalance to the onslaught of headlines so outrageous that, as someone who has written dystopian novels with eerily similar plot lines, I find myself feeling like the fantastic is somehow bleeding into consensus reality. The night after I heard the owls, I heard a group of men conducting what sounded like military drills in the park across the river—a different kind of call and response, the kind you hear between a sergeant and his soldiers. Not the first time I’ve heard that, either, in the past couple of years. What conception of springtime they are preparing for, I don’t know. It probably does not involve as much yardwork as mine.

The only development on our lot when we found it was a petroleum pipeline, wheel-hatched valve box and all, that had been built in the 1940s and abandoned in the 1990s. For many years it was unfenced, and the yard was littered with large quantities of demolition debris and other trash, including huge chunks of old roadbed, sewer pipes and walls. Before we bought the place, someone pushed most of that to the back of the lot with a bulldozer, mixed in with a lot of dirt, resulting in a bluff at the edge of the riparian floodplain that is essentially an unpermitted little landfill. Somehow it is also a grove of the healthiest looking hackberries I have ever seen, under whose shade every spring begins with an explosion of purple and pink spiderwort.

The phytoremediative qualities of certain species of spiderwort have been scientifically studied, most notably Tradescantia pallida, native to the Gulf Coast of Mexico, which has been shown to remove cadmium and other heavy metals from the soil. I don’t know if our plants, which must be Tradescantia virginiana (or some locally evolving variant of that rapidly hybridizing genus), do the same work. But when you see them coming up between the old chunks of curb cut, it easy to think they occupy that blighted ecological niche for a reason.

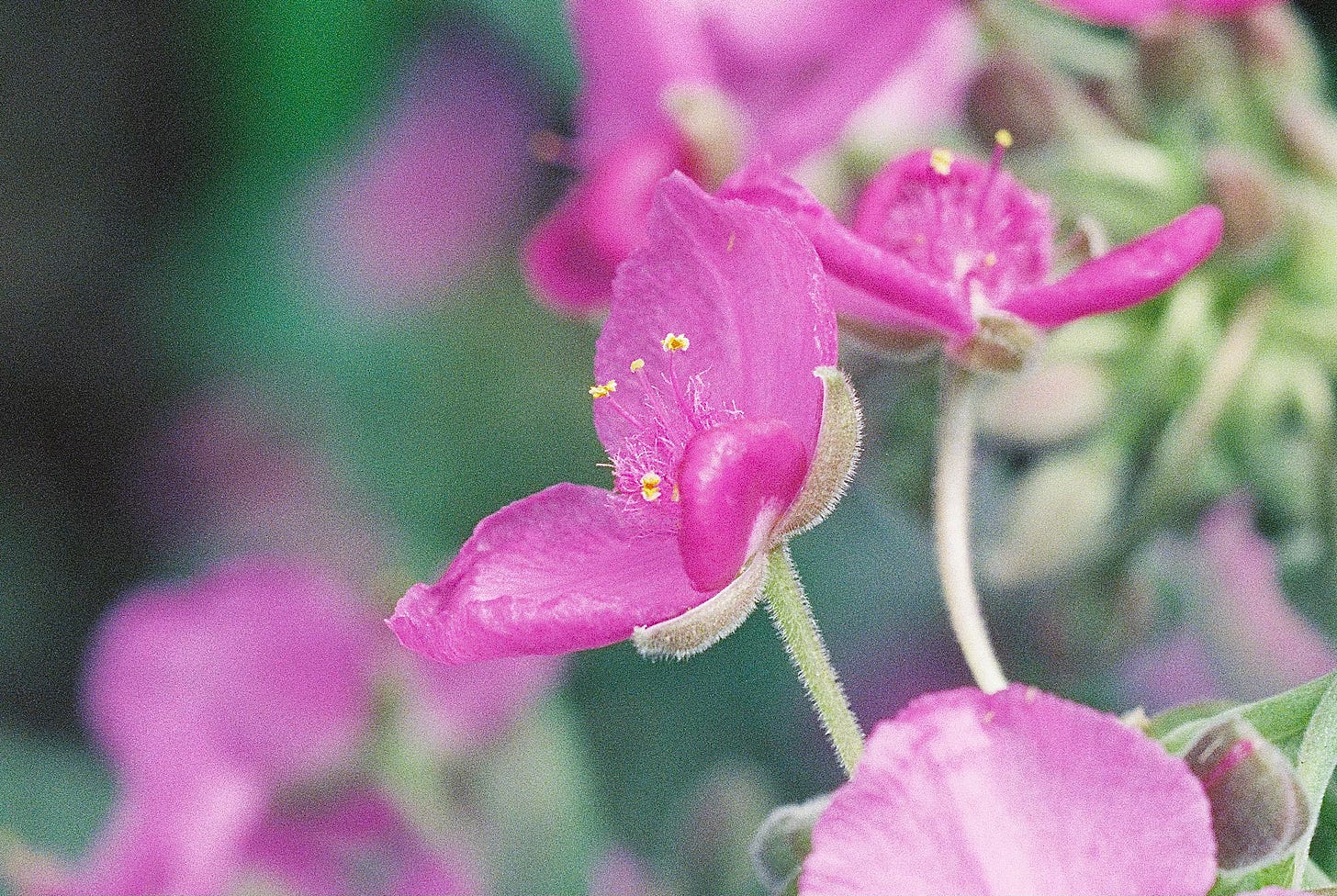

Last weekend after I got done weeding I grabbed my dad’s old Canon F1 film camera, put on the macro lens he used to use to take pictures of his patients’ teeth, and experimented with capturing the details of some of these gorgeous early wildflowers. I’ve mostly been keeping the camera loaded with CineStill 800T, a tungsten film designed for low light that works well on early morning walks. One of the pleasant quirks of the film is the blue tint it brings out, especially in the greens of the foliage. I like the results, which convey an emotional truth, even as they alter reality in subtle ways.

Pictured above is evening primrose, one of the first full sun native wildflowers to appear in Texas springtime. Famously hard to cultivate intentionally in the garden, but remarkably prodigious in places like roadside rights of way, drainage ditches and empty lots, it’s maybe the best exemplar of how the prairie ecologies we have largely erased from this landscape are not entirely gone.

After we built our little house, tucked into the ditch that was left when we removed the remains of the old pipeline, we worked to restore some of that native ecology, installing a green roof over our heads seeded with 70 species of flowers and grasses associated with the Blackland prairie. In subsequent seasons we did similar seedings across the rest of the yard, after solarizing it with big sheets of black plastic to try to mitigate the invasive ornamentals, and the results were remarkable.

Maintaining the balance of native and exotic species is a challenge. We are not puritans about that distinction, and even suspicious of it. But we have witnessed the indisputable biodiversity that the native plants seem to conjure from the ether in previously lifeless zones, and that’s our main objective. Busy with parenting and careers, we have slacked off a bit in the past five years, especially in the fight against brome grass, which comes up in winter and crowds out the natives.

We spent the past three years building a guest house, and the construction decimated the work we had done in the front yard. So this spring we have begun a new phase of rewilding, informed by the revelation over the course of the past 15 years that this weird little spot at the edge of the woods behind the factories does not want to be a prairie so much as a forest. With luck, we will be able to nurture it into something that recalls the sacred grove, even as it still shows the scars of our abuse.

Last Saturday I stayed up late reading a memoir of the Fourth Crusade I found while unpacking boxes of books that had been in storage. When I finally headed to bed, I stopped to listen to the sounds of life in the woods. I heard the call and response of a group of animals, and understood after a minute listening that they were not birds but frogs, who must have liked the spring rains we’ve been having.

I listened for a while longer, staring into the dark, locating each of the calls in space. I realized there were no more than six frogs, maybe as few as three. Then I remembered how when we first moved here in 2010, living in a little rented cottage next door while we figured out how to build our crazy house, we would hear hundreds of frogs croaking along the river all through the hot nights as we hung out on the porch. Maybe they will be back, when spring matures into summer. But amphibian life always seems like one of our most powerful indicators of ecological health, and I worry the river, after a decade of intense new development in its surroundings, may no longer be as clean as it was.

Friday night I heard one of the owls again. It was in a tree on the far bank, near the beach where I had heard those men assembled as if preparing for battle.

The next day I found myself thinking about the myriad ways human cultures have appropriated the owl as symbol, often focused on its gifts of navigating through the darkness. We’ve associated it with everything from military victory to alien abductions, both devil and redeemer, using it as a mirror for the aspects of our own minds we can’t quite fathom. The owls probably can’t help us navigate through the dark human moment that is emerging. But they and the other life around us have a lot to teach about the world we have made. And the world that could be, after the dying old beast currently thrashing around on our screens and in our heads has lashed out for the last time.

The Roundup

Welcome to all the new subscribers who have found their way to this newsletter thanks in large part to Austin Kleon, author of Steal Like an Artist and other bestselling guides to living a richer and more creative life, who reported last week how two people in two days recommended he check out A Natural History of Empty Lots—and shared an amazing image of an inchworm crawling across his copy.

Thanks also Akash Singh and the folks at STIR World for this lovely piece on the book, and the great selection of photos they included.

For those encountering this work for the first time, Field Notes is a mostly bi-weekly letter from the urban outdoors, usually from the edgelands of Austin, Texas, where I live with my family, and occasionally from farther fields. My most recent book digs into similar material at longer length. Before starting this newsletter in 2020, I was best known for my SF novels, and I also practice law. For a sampling of the most popular posts, check out the archive. All posts are free, all photos are by me unless otherwise noted, and I may repeat myself from time to time.

For the reader who asked for a picture of the new puppy we recently adopted, here’s the 3-month-old terrier our daughter named Fifi:

The London Review of Books has been really on its game of late, with some incisive perspectives on the headlines, including Judith Butler on Executive Order 14168, Perry Anderson on what comes after the deadlocked conflict between neoliberalism and populism (and whether it can happen without a new theory of political economy), Deborah Friedell on what two recent write-ups of the makeover of X reveal about what’s going on in Washington, and Thom Dyke on the Gitmo tribunals today.

When I went to get my haircut Thursday, the barbers had two different Val Kilmer movies on in memoriam: Maverick in one chair and the wonderfully insane 1996 adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau in the other. RIP.

I was also sorry to read this week of the passing of Gai Gherardi, the lead designer and entrepreneur behind L.A. Eyeworks, whose frames I have been wearing for 30 years.

Kudos to our friend and colleague Meghan McCarron for her amazing piece in the Times about the decline of the casual family restaurant and its central role in American culture.

Thanks to Mishka Westell for teaching me that the preferred term for bird-watchers in England (at least some of them) is “twitchers.” And that they’ve been seeing a pileated woodpecker in Austin’s Roy Guerrero Park. In other local birding news, thanks to Jennifer Bristol for the heads up about the legislative threat to the golden-cheeked warbler’s habitat.

In environmental news, this NYT piece about the toxic algal blooms off the Southern California coast had the most bummer paragraph I’ve read in a while:

Local governments have put out advisories warning the public not to come close to stranded animals. As the springtime weather brings crowds out to the beaches, parts of the shoreline of Southern California have had a grim feel. Creatures that typically give children and adults a thrill when they’re spotted splashing in the water now turn up in the sand dazed or dead, spreading a sadness that clashes with the bright sunshine and ocean breeze.

Better news from Nebraska, where a record-high 736,000 sandhill cranes migrated through last week (with no observed cases of bird flu). Here’s a CBS Sunday Morning video from the Platte River near Grand Isle:

Have a safe week.

The link didn't work for the Judith Butler piece, but I found it and thought I'd share it here. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v47/n06/judith-butler/this-is-wrong

Excellent and thought-provoking piece as usual.

Thank you for your wonderful newsletter. Not important, but the preferred term for a bird watcher in the UK (like me) is just bird watcher, or sometimes birder for people who are more serious about it. Twitcher is specifically for bird watchers who travel long distances for specific rare sightings. Your Wikipedia link (sort of) explains this. I have a life list, and visit reserves fairly regularly, but wouldn't call myself a 'birder', and certainly not a 'twitcher'.