Blood Moons, Brutalist Plants and Trans-Neptunian Objects

No. 175

Last Friday morning when I went to put the trash out a little after sunup, I found someone standing in our driveway just outside the front gate, right where the sidewalk ends. A woman, with her back to me, wearing a well-used black day pack over a plaid shirt and jeans. She was looking down, recording notes. I stepped out to greet her. She said how cool it was we live in an earth shelter, and asked how long we’d been here. I told her, and then asked what she was up to. Turned out she had been out all night, watching the Blood Moon come and go.

The total lunar eclipse of what the almanac writers call the Worm Moon began at just after midnight that Friday and continued for a few hours, though it was gone when I got up at five. I didn’t ask where she had watched it from, but it sounded like she had stayed close to the river. I asked her what the Moon looked like, and the answer was in her eyes. You could tell she was looking to get more of that wonder on her walk home. I mentioned some cool hidden spots she could check out along the way, but it’s hard to imagine anything cooler than what she had spent her night doing: soaking up the celestial majesty that still manages to outshine the electric hubris of the human city a few nights of the year, even if it does so when only a few of us are looking.

I later wondered if she’d heard about the 128 new moons of Saturn. I had read about the previously unobserved celestial objects in the news the day before. The discovery had been officially certified by the fellows of the Minor Planet Center, in a series of electronic circulars titled like chapbooks of experimental poetry even though they are not:

Each observation is expressed mathematically, in encrypted notation that I suspect would translate well into an album of ambient music. The right to name the moons, in accordance with the practices of the International Astronomical Union, is given to the scientist who led the discovery team, Edward Ashton of the Academia Sinica in Taiwan (whose other publications include the awesomely titled “Lightcurves of 371 Trans-Neptunian Objects”). The expectation seems to be that, like the other outer moons among the 146 previously identified, they will be named after the Jötunn of Norse mythology. Begging the question of how many such names are even known to us from the surviving written records.

Turns out there are a lot, from Aurvandil the luminous wanderer to Ymir the seething clay. And Aurvandil is already in the sky. Or at least his toe, ever since Thor tossed it up there when it froze as he was carrying the giant across the river. We just don’t know which star. Even though, or maybe because, Aurvandil aka Ēarendel lived on in the sky as the redeeming angel of Advent. We do know that it is one of the stars that appear in the morning to early risers, making me wonder if I have seen it and did not know.

The Worm Moon lived up to its name this year, appearing just as the first native wildflowers began to bloom and the warm weather insects began to appear, in the week of the equinox. I found evening primrose opening up along the loop road, across from the ruins of the old dairy plant. A big patch of bluebonnets spread across the high berm between the tollway onramps, brightening the view for the morning commuters. The first orange bracts of the plant the settlers called Indian paintbrush came up outside the recently abandoned temporary Austin headquarters of the social media wasteland formerly known as Twitter.

Closer to home, I spotted some Corydalis, the early bloomer known as scrambled eggs for its nodular blossoms of bright rich yellow, poking through last year’s growth on our green roof. And in the back of our yard, where the soil is still littered with chunks of concrete demolition debris and other trash illegally dumped here decades ago on what was an empty lot, the deep green clumps of phytoremediative spiderwort have burst with their velvet blossoms a little later than usual.

The everyday miracle of native plants surviving in the brutalized landscape of our erasure sometimes induces me to try fresh variations on facile remarks about the eternal certainty of springtime’s return. This season I’m more preoccupied with how persistently the worst qualities of human tribalism, territoriality and addiction to patriarchal power structures reassert themselves whenever the possibility of meaningful change starts to express itself in the culture, as it did in the aftermath of the Great War and the global shutdown of pandemic. The wildflowers and butterflies sneaking their little remnants of faerie into the Texas hellscape does remind me, though, of how those divergent things are connected—how our CEO cults and the warlord models they descend from are ultimately rooted in our control over wild nature and ability to extract surplus through that dominion. And how the path to our own liberation must run through the wild, biodiverse garden we have the capacity to bring back to the world.

Our six-year-old daughter helps us stay yoked to a more promising vision of the future that could come after the current clowns in charge are long gone. Friday she insisted her mom take her down to the river to swim, maybe drawn by the knowledge of the bluebonnets in bloom along the banks, or by some more primal call of that wild stream that connects us to deep time. Saturday I took her back, in the canoe, and she learned for the first time how to find the birds by their songs, how to spot the turtles in the water after they slide off the rocks, and how to properly paddle your way forward against the current, one stroke at a time.

When we got to the dam, we got out so she could run along the rocky limestone bank, where you can still see the ruts worn by wagon wheels when this was a low water crossing. As she splashed in the puddles and looked for the little holes where the eels live out their hermaphroditic adolescence before they return to the Sargasso Sea to breed, I went to check out a flash of yellow further back. Golden pom poms of the huisache tree, growing up from rocks and concrete rubble at the base of the bluff behind the International Bank of Commerce branch. Those blossoms of our American acacia are among spring’s most ephemeral and beautiful manifestations around here. The bark of the tree is said to produce a potent hallucinogen, but I’m happy to just smell the flowers.

When we returned home, I went to check on our own huisache trees at the edge of our yard. We have three, which had grown pretty big and bountiful over the years, until the winter storm of 2021 and the hard freeze of the following winter. They turned black afterwards, and seemed entirely dead. But after pruning back most of the dead branches, over the seasons they slowly produced new growth. And this year, finally, one produced blossoms again. Go tell Aurvandil.

Spring Break Reading

Happy birthday to my son Hugo Nakashima-Brown, one of the finest exemplars of humanity I am lucky to know (yes, I am biased, but others can vouch), who turns 30 today. You can check out his amazing work here.

Seeking less polluted night skies, we made a three-day run last weekend out to West Texas, and made a coffee stop at Front Street Books in Alpine, which may be the best-curated small town shop I’ve ever seen. We met new owner Kendra DuBois, who just took over the store, and hope to get back out there for an event soon. If you’re looking for spring reading, especially on desert ecology or Western history, check out their inventory.

On the way out, we stopped at an Exxon station that is the only remaining human habitation in the ghost town of Bakersfield, which existed briefly at the base of the landmark known as Tunas Peak—a mesa along the ancient trailway that I-10 tracks known for its resemblance at most angles to the bosom of Gaia (which resemblance earned it some other names). That got me reading up on the fascinating archaeological history of the site.

When we returned, my daughter and I took Oma to check out the exhibition on children’s literature at the Harry Ransom Center, which has some amazing artifacts from classics of the genre, as well as remarkable examples of juvenile writing by great novelists—including a kid’s notebook filled with Norman Mailer’s unpublished story of the Martian invasion.

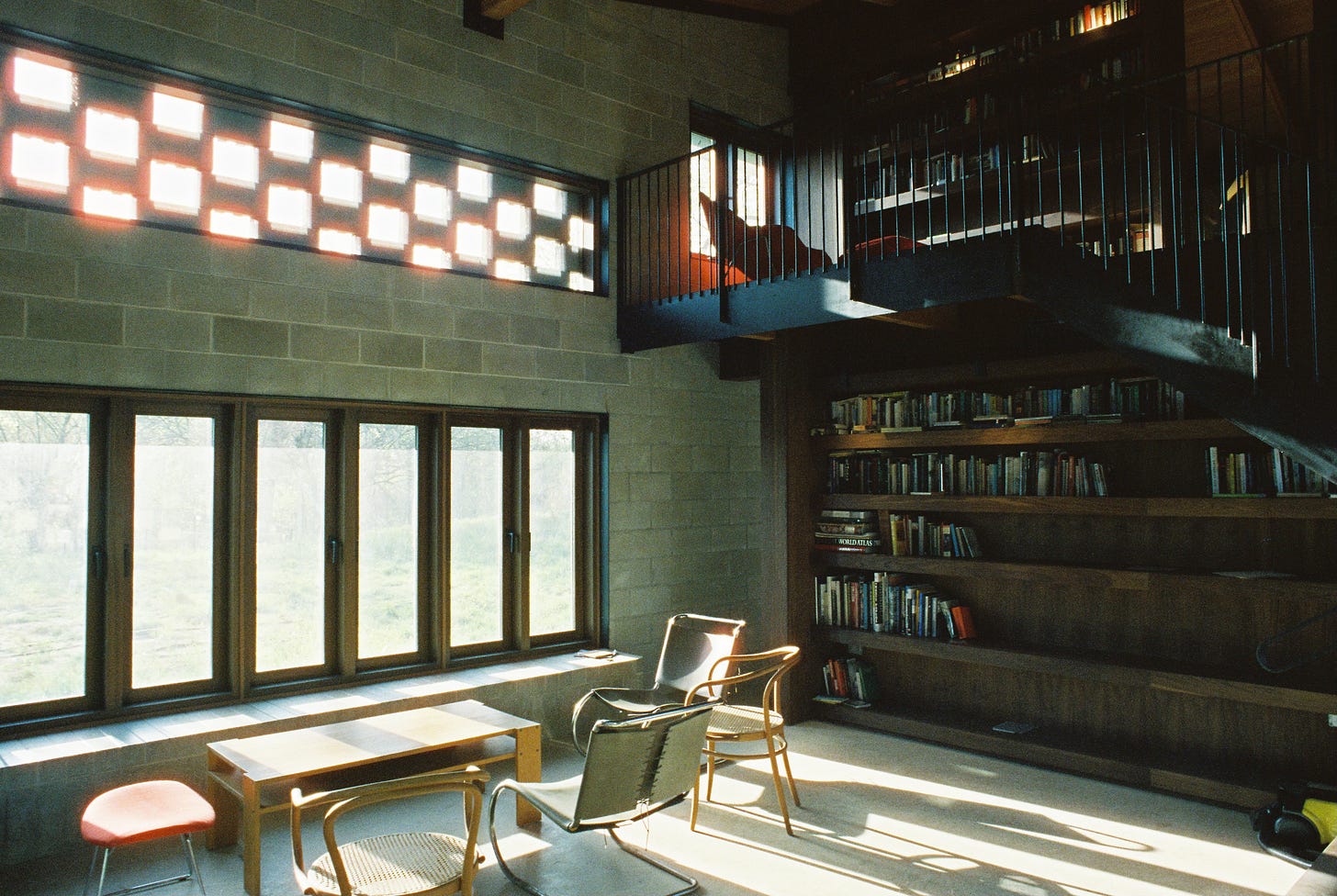

At the end of last year we finished construction on a new guest house on our lot that my wife Agustina designed, to provide space for big brother and his bride-to-be and other visiting friends and family, as well as proper home offices for Agustina and me, and space for our books. In the evenings I’ve been unpacking them box by box, and enjoying the rediscovery as I figure out my shelving system. A few of them provided source material for this post, including Hilda Davidson’s Gods and Myths of Northern Europe, my copy of which is a used Penguin first edition as old as me but less beat-up, Brutalist Plants by Olivia Broome, and R. Crumb’s graphic novel adaptation of the Book of Genesis.

For a really cool Texas library, check out Donald Judd’s in Marfa, which now has a pretty great online facsimile.

I was delighted to see the audiobook of A Natural History of Empty Lots narrated by yours truly included in this Audiofile magazine roundup of “Spring Awakenings: Stories of Nature, Renewal, and Connection.” And I loved the take Akash Singh had on Empty Lots in this piece for the design site STIR.

Lastly, while we were in Alpine our 3-month-old puppy and I went out for a little Sunday morning hike last week on the hills behind Sul Ross State University, where we discovered the desk students dragged up there for outdoor study in the early 80s, and experienced the wonder of the sun rising over the Big Bend, which I captured on my dad’s old F1 film camera:

Have a great week.

I'm going back to finish the rest of this Note, but the beginning story about your eclipse-watcher visitor was absolutely lovely. Thanks for that.

the big BIG news; "three month old puppy." though the guest house/office/library is pretty cool too. and what are those pink flowers? thanks you happy spring