Jackdaws, Freeways and Aztecs

No. 174

February is the season of grackles and concrete. Black birds gathering in gigantic flocks in the same places where we jam together in our cars, as if the cast-in-place guardrails and steel lampposts will provide them some camouflage. I saw them every night this week at the tail end of rush hour, coming in to sit on the edges of the upper deck of Interstate 35 where it passes over the main streets at the east end of downtown Austin. Birds with weirdly tropical energy, vocalizing the crackle and whine of a hundred old radios tuning between channels. When their high-pitched squawks penetrate the machine bubble of your car as you listen to the evening news roundup and wait for the light to change, you might wonder if it’s a cue to change the frequency through which you are experiencing the world.

That hideous frontage road where I saw them was a lovely boulevard once, until the urban planners made it a wall to reinforce the line of segregation, and an artery for the commerce that flows across our northern and southern borders. Like a lot of major roads, it follows much older migratory pathways, but the buffalo are almost as gone as the mastodons, there hasn’t been cattle drive from south Texas to Kansas in more than a century, and the monarch butterflies that are left avoid the most urbanized stretches of that corridor. When you see them gathering there as the sun goes down, night after night, you can’t help but wonder why they choose that otherwise lifeless machine artery as the roost for their squawking slumber.

The scientists would tell you the grackles like to congregate in zones where cars go—places like frontage roads, parking lots, and old malls—because of the light they are filled with at night, the puddles of water that accumulate on the pavement, the food trash to be found in the alleys behind grocery stores and restaurants, and the paucity of predators, even cats. But there’s something more to the message of their presence. Like when you learn they really only showed up in these parts around the same time as cars and trucks started taking over the roads. And when you learn they have been living in cities and stealing people’s tortillas far longer than there has been a USA.

The grackles have been working their way up here for almost 600 years, since Moctezuma’s uncle Ahuizotl imported them to Tenochtitlan. The Aztecs loved birds and treasured their feathers, and developed a specialized profession of long-distance bird smugglers to fill their aviaries. Ahuizotl so liked the bird he named Teotzanatl—divine grackle—that he encouraged they be fed by humans. Quickly, they learned to eat everything the city made available to them.

This week I read how the first of the Aztec’s imported grackles came from the tropical coast along the Gulf. That made me wonder what it was they called that body of water. One of the ways it was known was as the house of the goddess of the sea, Chalchiuhtlicueye. When she was tormented, the stories say, her tears flooded the world.

Maybe she will come back at summer’s end, and let us know her true name.

I’ve been attending to a lot of correspondence this week with friends and family in the UK and Europe that has made me feel compelled to apologize for my country’s politics. One such note started with a friend in London sending me a link to a news article I had already read, which led to a back and forth in which we debated how much what is going on right now is just the “tarp pulled off” (his words) to reveal what has always been at least one aspect of the true character of the collective American personality.

I have also gotten a lot of notes and tags in my feed over the past couple of weeks about how the scenarios playing out in the news remind some folks of my novels, especially my first novel, Tropic of Kansas, which I wrote in 2012-2014, and which tells the story of characters who become caught up in a popular uprising to overthrow a charismatic CEO become fascist American president running the country like a business corporation. A book that seemed so implausible when I finished it that I wasn’t sure I wanted to send it out, and when it was published three years later NPR called it “eerily prescient.”

This weekend I stumbled upon some photos I had taken while I was working on the book in the summer of 2012, using my Tumblr as a kind of mood board. Lots of pictures of books that captured the half-baked idea of marrying the narrative tropes of adventure pulps with radical political theory, in an effort to bite a little more deeply into the copper wire and have fun along the way. As with most such undertakings, you always feel like you came close, but not as close as you would like. And with a first novel, you can’t help but cringe when you look back and think how much better you could have done if you knew what you know now.

The most important lesson I learned working on that book, through the eyes of its characters, was how the social and political injustices of their imagined world (which was a mirror of ours) were deeply rooted in the damaged relationship the people had with the land on which they lived. That, and the value of remembering to maintain the perspective of the long view, even as you attend to the urgent challenges of the right now. Like when one of the main characters realizes, after someone explains to him what the star of Texas on a beer can represents, “I guess every place was another country once. And will be again.”

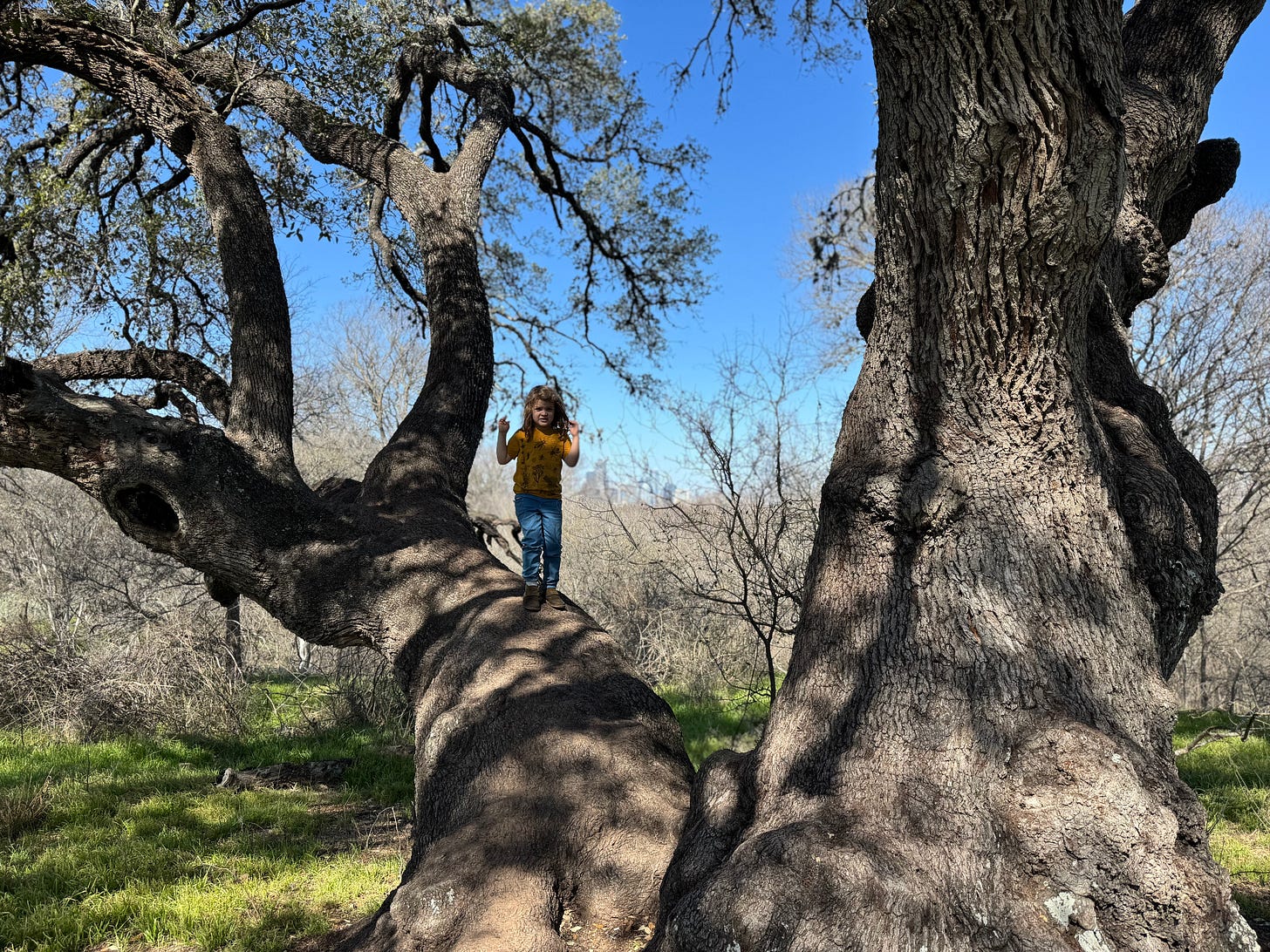

Saturday morning my 5-year-old daughter and I joined a group of volunteers working on restoration work at one of the riparian parks across the river from us. The idea came from one of my law partners, a longtime parks advocate who invited everyone in our small office to join, and got a few takers. Since this season’s venue was so close to our home, and the work run by a close friend who is one of our community’s leading stewards of urban nature (and the guy who I asked when, working on Tropic of Kansas, I needed to know what it feels like to be shot with a rubber bullet), I couldn’t not go.

For my daughter, there was a little bit of work and a lot of wheelbarrow rides. When we were done mulching the trail through the arboretum, we walked further back to see the old oaks hidden behind the maintenance barn and the bus turnaround at the end of the road. There are three big, ancient trees there. And this season, the biggest and oldest of them was especially magical.

The city arborist estimated that tree to be around eight centuries old. If you brave the expansive patches of prickly pear around it, and walk the zone under its canopy, you can experience what it’s like to step through the portal the fabulists promised you would find. In moments like now, that’s a special gift. And a reminder that they are coming for all the great trees, and it’s up to us to protect them.

Further Reading

For more on grackles and the Aztecs, check out my post from this time last year, “Ahuizotl’s Gift,” and all the related links it included.

On the question of what really is the true name of the Gulf of Mexico, my friend the author, professor and scholar of Nahuatl David Bowles has a great piece at Medium.

Also at Medium, my 2017 piece on the idea of running the government like a corporation—“You’re Fired—Democracy, Dystopia, and the Cult of the CEO”—feels like it may be worth revisiting.

I think what really got me thinking about Tropic of Kansas this past couple of weeks was this lovely piece by Carmen Gilmore about urban edgelands and my book A Natural History of Empty Lots at the Canadian environmental history journal NiCHE— “From Vacant to Vital: Rethinking the Role of Empty Lots in North American Cities.” Tropic of Kansas opens with an orphaned son of American political dissidents living in the woods on the outskirts of Winnipeg and stealing food from suburban yards when he can, and reading Carmen’s accounting of such spaces in the Western Canadian context took me back to that place.

If you haven’t read Empty Lots yet (or have someone you might like to give a copy), the hardcover is still on sale at my least favorite online bookseller.

At the nexus of conservation and our political moment, this latest dispatch from Michelle Nijhuis at her Substack really landed:

As did this post this morning from the English SF writer and biologist Paul McAuley:

This post marks five years of this newsletter, which began in February 2020 as an experiment in what my fiction editor at the time aptly called “dystopian nature writing”—a sandbox to play around with the material I had been accumulating over the years here at the edges of East Austin and that had begun to infiltrate my novels. It proved more successful than I anticipated, spawning a book and attracting thousands of weekly readers from amazingly diverse backgrounds.

When I started it, my aim was to do it every week for a year. I managed the weekly schedule for two and a half years, until book writing and other obligations made it more sporadic. A lesser frequency feels okay to me, in such a saturated media environment. I aim to continue it, mostly bi-weekly, and to start developing some new material that comes at it from a fresh angle. I think I’ll keep the subscription button off, just because something about that feature bugs me, feels like it’s feeding the problem that has gotten us to this point.

Thanks to everyone who has supported this project as a reader and otherwise. If you’re interested in checking out the archive of past installments, you can do so here.

Wishing you a peaceful beginning to the new month, and signs of spring between now and the Ides of March.

Love your writing, I look forward to it! Beautiful assemblage this time, grackles v much included.

I stand and quietly applaud.

Sometimes I think we should pause the writing of dystopic fiction. It seems that whatever future one comes up with, no matter how unpleasant, how twisted, how repugnant, there’s some character somewhere who has been successful at outsized accumulation of wealth going “*That’s what I’m talkin’ about!!*”

Some respite is needed. Nothing has healed. We’re just no longer noticing the pain.

But the grackles are loud. And happy. And somehow just living their best life.

Thank you.