A slice of pecan pie for the banished Titan

No. 169

The day before Thanksgiving I spotted a guy foraging in this gnarliest of empty lots pictured above. The spot he’d picked is a little quarter-acre on the road out of town, an expanse of freshly bulldozed dirt dappled with the grey, pebble-sized remnants of the truck spring repair shop that previously occupied the site. An unlikely place to find wild food, you might think, but maybe an easier background against which to spot the pecans that have fallen from those two beat-up trees now more conspicuously visible along the right of way.

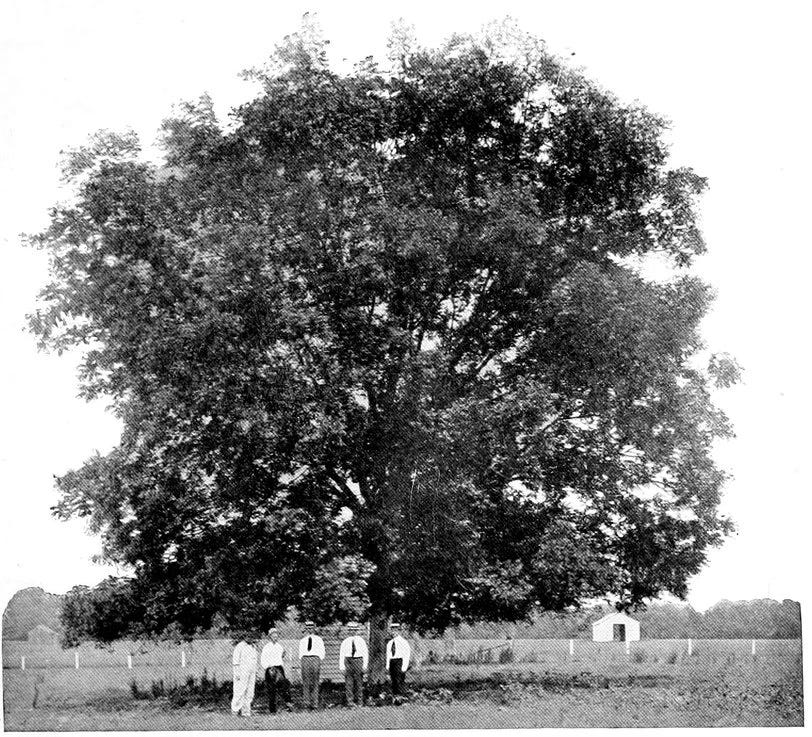

Pecan foragers are a common sight in the zone along that road. There are a lot of pecan trees around here, in the alluvial uplands of the Colorado River floodplain, not far from the ancestral habitat in which the species evolved three hours to our south. Pecans grow tall, usually in groves abundant enough in their production to make up for the fact that the typical tree only fruits biennially. The nuts are the tastiest to humans of any of the native trees that grow here, and when you see someone with a plastic bag shuffling around under their canopy, you are reminded that people have been doing that in this place for thousands of years. The only thing that’s changed is that in the last century they learned to mostly do it for money, selling wild foraged food like collected cans to an industry that produces 60 million tons a year just in Texas. The going rate this season is 40 cents a pound.

While we still have enough to support some marginal foragers, there are far fewer pecans here today, as the pecan trees of Central and East Austin also stand in the way of the redevelopment trying to remake these flat acres into an extension of downtown, and even the homeowners who live under their canopies often gripe about how much work it is to clean up the hard, dark fruit that rains down every other fall. Most of haven’t ever needed to learn to see the food for free that surrounds us. It doesn’t help that the groves that would have beckoned earlier human inhabitants like arboreal cathedrals rising up out of the prairie are almost all gone, the remaining trees confined to the interstitial spaces the city leaves between buildings and roads.

I had never taken notice of those trees outside the repair shop, despite walking and driving past that spot thousands of times over the 15 years we’ve lived over here. I only ever noticed the building that stood on that corner, which was pretty basic: a beige cinder block shed that served as a hangar to service big old trucks. What certified the place’s charisma was the logo hand-painted on the east wall, with the image of Atlas using a set of truck springs to help him hold up the world.

Maybe it is because of his banishment to the other side of the horizon that we tend to forget the reason Atlas was burdened with that labor. Atlas helped a tyrannical father try to maintain his power, serving as deputy to Cronus in his effort to put down the rebellion led by Zeus, but the old gods lost to the insurgent Olympians, who were aided by Atlas’ brother Prometheus. And as punishment, Atlas became the patron saint of old guys who never get to stop working, which may explain the intuitive attraction his truck shop icon always had for me.

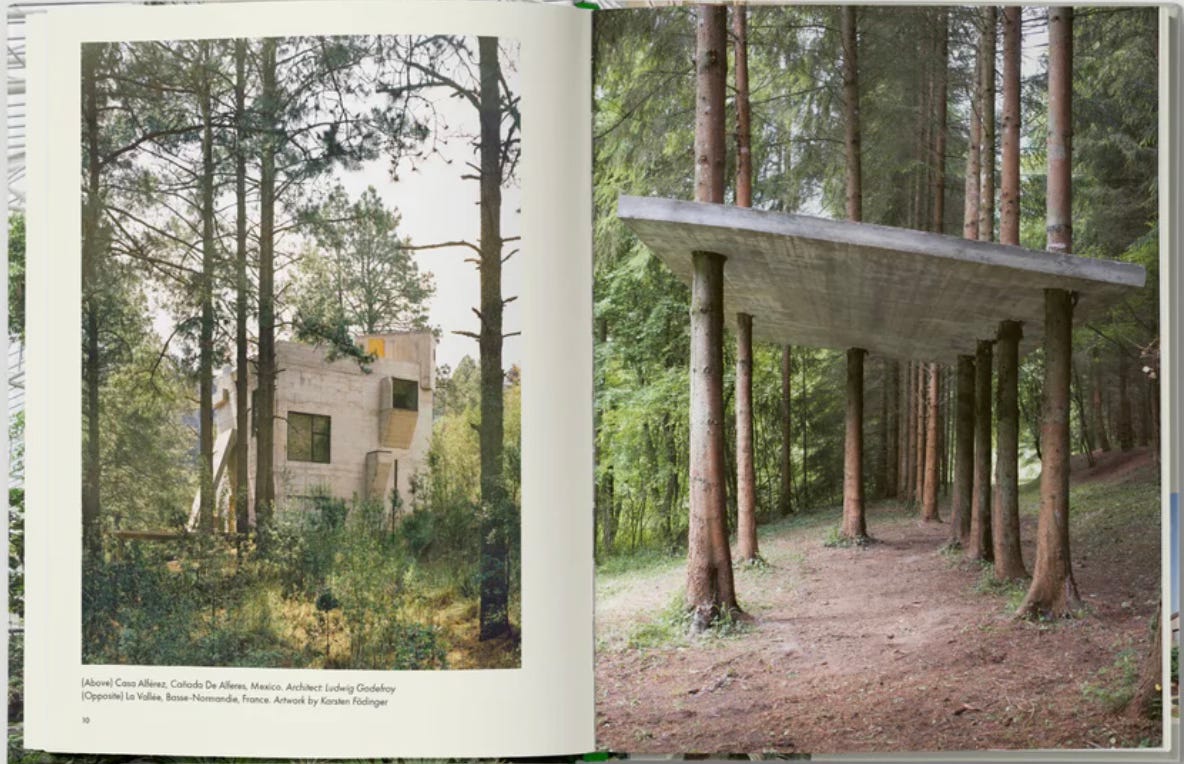

The business that was on that lot did not die. It just moved further out to the new edge of town, in a newer building along the highway by the airport. With luck, the family that owns the business also owned that lot, and cashed in on its sale. The trees they left behind are protected, more or less, and will hopefully keep dropping fruit right next to the sidewalk for decades to come. But even protected trees are always endangered when they get in the way of more rent-generating uses of the land on which they grow. I will probably never know what happened to the once-hidden grove of old pecans that stood on the deserted traffic island down the road from there, closer to our place, after they were uprooted last winter to make room for a brutalist parking garage. Maybe the trucks put them on a ship for transport to a real island, beyond the mists of the Western Sea, even if that’s where elves normally go to retire, not Ents.

When I went to get buttermilk at the grocery store Thanksgiving morning, I was tempted by a curious tome for sale in the checkout stand, next to the tabloids and the laminated pocket field guides unironically selling you the dream of getting your food for free as you stand in line to pay for it. TEXAS OBLIVION: Mysterious Disappearances, Escapes and Cover-Ups, is a title that compels your attention, encoding an invitation to a liminal zone between the real world and the dream it projects. On sale for $21, the copy already damaged from other curious browsers, the book collected weird 70s and 80s newspaper fodder at the edge of urban legend, all about Texans who vanished from official reality. An alluring fantasy, in a state whose colonial settler mythology weirdly mixes the dream of escape from the law by crossing a border with the power trip of learning you can now impose your own law on the people who already occupy the place you escape to.

The most challenging question I got asked on my tour to promote the launch of A Natural History of Empty Lots was probably the third one I got last Thursday night at Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle, asking, a week before Thanksgiving, how I think about incorporating Indigenous thinking, tradition and life into my white boy evangelization about rewilding the city and the future (my paraphrase). I answered by saying that I have been lucky to learn from friends, neighbors and fellow activists from Indigenous backgrounds who have helped me see the world through their eyes, with a familial conception of the natural world, but that I don’t presume to be able to speak from any cultural tradition but my own. The book, I explained, tries to get to a similar place from a different origin point, by inverting our (or at least my) own linguistic programming to reprogram the way we see the other life around us, hacking the boundaries urban life under capitalism creates between us and “nature,” and interrogating the legal regimes that rationalize our conquest-based dominion.

I also tried to describe to the Seattle audience how different the contemporary Indigenous presence is in the human ecology of Texas—a place where the colonial era efforts to exterminate and evict the prior inhabitants of the land were ungoverned by any of the pretexts of due process that applied in the United States, but where the cultures they claim to have erased remain more vividly present all around you, once you learn to see them.

On Thanksgiving morning, walking the dog in the woods behind the factories, I came upon a little patch of wild onion. It was near a pile of floodplain trash someone had collected but never picked up, at the side of a track plowed through the nature preserve by dirt bikers over the past two summers. Deer had nibbled at the leaves and scraped some of the dirt at the base to see what was there, but left the bulb. So I harvested one, in the complicated spirit of the holiday. When I got it home, it turned out to be a double bulb. I had thought I would throw it in with the green beans, but then started worrying about what toxins it might have taken from that dirt, and saved it for my own weekend omelette.

Later that morning, before we went to gather with the extended family for the feast that commemorates the end of the fall harvest and the beginning of winter, my daughter came back out with me into those same woods. I showed her the wild onions that were still there, but she was more interested in finding Anthropocene Easter eggs. In particular, she wanted to see the giant echo chamber I had been pictured visiting in the newspaper—a big drainage pipe that empties into the floodplain behind our home.

We found signs that a family of ringtail cats may be living in the gabion around the pipe, which I plan to investigate in the coming weeks. Octavia declared her plans to explore more deeply into the dark tunnel, with or without a flashlight. She collected a magical spring from the mesh—probably the remains of a stainless steel egg whisker. And then, a little further on, I looked back to see she had transformed a wound coil of HVAC tubing into a power bracelet.

It got me thinking, when I pull out our beat-up copy of D’Aulaire’s Greek Myths to read at bedtime, maybe we should start making our own reinventions of those stories, and sampling other mythologies with a little more forethought. Tales of the new generation uniting to depose tyrannical father figures have their place, especially in times like these, but we may need to work harder at imagining what could come after the uprising than the installation of a different king. It’s probably up to Octavia and her schoolmates to write their own stories, but perhaps we can help them see the myths of the future hidden between the lines of the ones we’ve inherited.

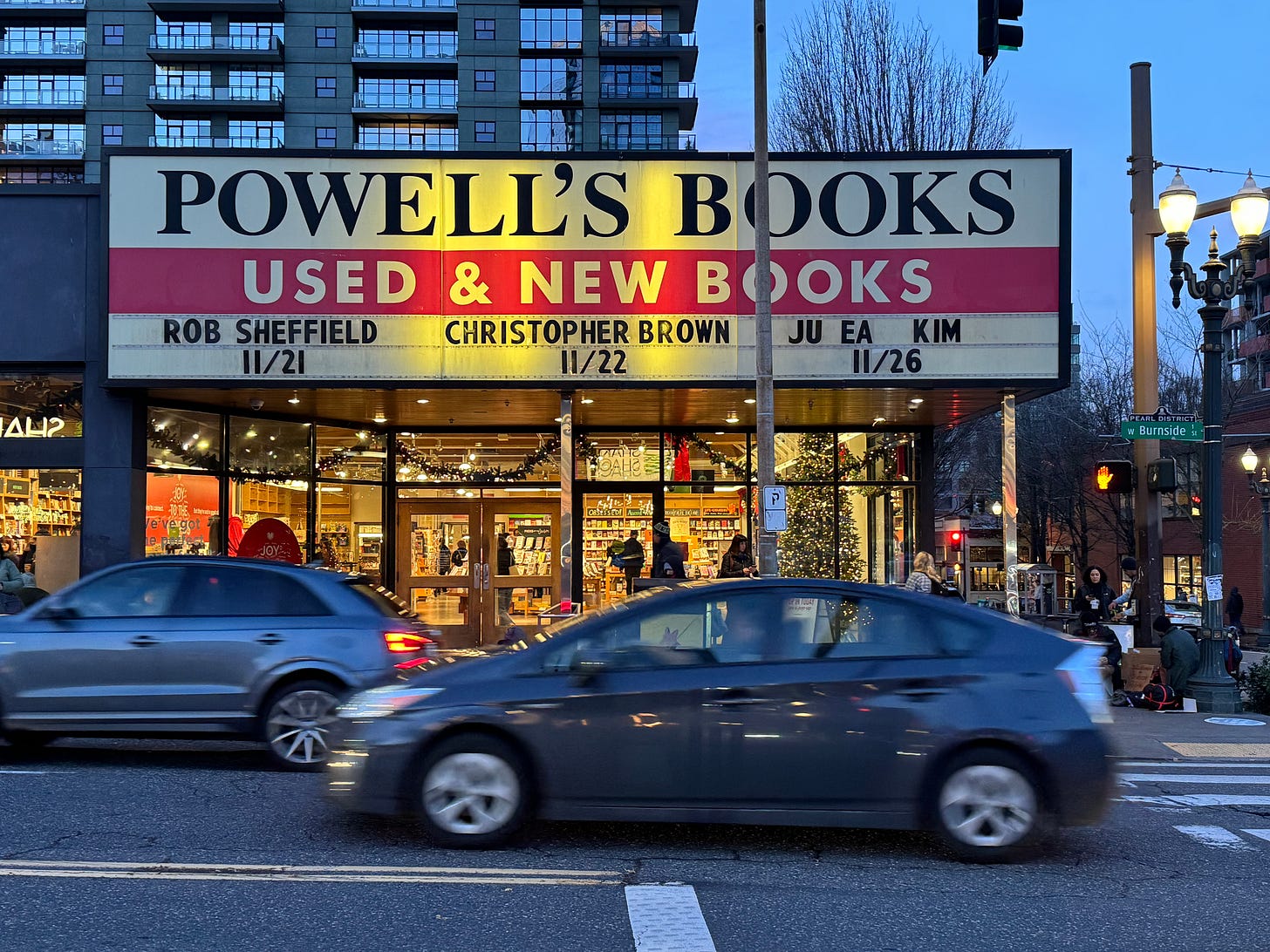

The Roundup

Thanks to the wonderful crowds who joined me for with Sarah Wilson at the Texas Book Festival, with Eileen Gunn at Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle (where A Natural History of Empty Lots is a staff pick for the holidays), and with Michelle Nijhuis at Powell’s in Portland (where Empty Lots is also a staff pick). It’s always awesome to see them have to pull more chairs out for the gathering crowd, as at Powell’s, but I was sorry to hear some 50 folks got turned away when we reached capacity at Texas Book Festival. If you were one of those folks, I’d be happy to send you a copy of the print version of this newsletter I did as a preorder promotion earlier this fall—just email me at chris at christopher brown.com. And there should be a couple more local events in Austin before winter’s out—watch this space.

I had a blast talking live last week with Larry Meiller for his statewide broadcast on Wisconsin Public Radio, and loved all the amazing, smart questions from the callers. You can listen to the replay here (I’m on the first hour).

I also had a tremendous conversation with urban forester Michael Yadrick at the Treehugger podcast.

In Seattle, I got to do some old school morning TV on the New Day Northwest show on KING 5.Thanks to the team there for having me in.

I really dug this latest installment from Rebecca Wisent in the new project she is doing: documenting the coming administration from the perspective of an environmental lawyer. Please consider subscribing, if that sounds of interest—Rebecca does an amazing coupling nature writing with advocacy and legal expertise, and also has done tremendous work compiling all the emergent nature writing on Substack.

In archaeology news, they found more Nazca lines. No, they are probably not the runways of ancient aviators, as Leonard Nimoy suggested on the show our 8th grade English teacher liked to replay for us with an unreliable film projector in the 70s, but I’m glad that video is easily streamable to keep the dreams of Erich von Däniken alive:

My daughter and I caught a family matinee of Moana 2 Saturday. It was better than I expected, complete with a scene in which the young hero appears to have an entheogenic trip induced by some milky sacred waters, a really cool giant clam monster, and a lot of blue ocean.

Lastly, I’m digging this cool book on Brutalist Plants by Olivia Broome, available from publisher Hoxton Mini Press.

And if you have anyone on your holiday list who you think might enjoy A Natural History of Empty Lots, Hachette has a 30% discount sitewide.

Speaking of brutalist plants, my daughter and I found this purple beauty blooming as winter begins, not far from the drainage ditch. If you recognize the species, please let me know in the comments, as I’m having trouble identifying it.

Have a great week.

Looks like maybe a Mexican petunia?

Christopher, thanks for linking to my post above. You sent quite a few new readers my way. Unrelated, did you see that the editor of The Revelator listed Empty Lots at the top of his list of 20 books to read this year? He described it as “quite possibly the best ecology book I’ve ever read”—this from a guy who is probably the most likely to have read alllll the ecology books.

https://therevelator.org/environmental-books-inspire-dec2024/