When Jackdaws Attack

Friday afternoon, in the heart of downtown Austin, I was attacked by wild animals.

It was my first trip into our central business district since early March. The vibe was weird as I rolled down Sixth Street past the boarded-up bars, few signs of human life other than the folks camped under the interstate and down in the concrete creek, and the cops out on patrol. The windows along the street are all covered with particle board, which in turn has been repurposed as the canvas for the fresh street art incubated in quarantine.

My destination was Sixth & Congress, the heart of downtown, so I parked around the corner by the Omni Hotel building up the hill. I used to work in that building (it’s half hotel and half office tower), and have experienced a fair amount of weird stuff there over the years. The last time I parked there I had a close encounter with Alex Jones, looking for his car with the same squinting intensity he uses to search for members of the Bilderberg Group. Years earlier, I bumped into Chuck Woolery in the lobby. The building is supposedly haunted by a guy who couldn’t pay his bar tab and jumped from one of the balconies, and a few years ago a deranged entrepreneur from the top floor tech incubator showed up with a rifle and shot two people in the lobby before being killed by the police. It may not be on the site of an Indian burial ground, but on one of those panels of 80s marble there’s a plaque noting that on that ground once stood the mansion of Mirabeau Lamar, the last President of the Republic of Texas and our first governor, the one who famously invaded New Mexico and advocated the “total extinction” of the indigenous peoples of this region.

Not having to worry about active shooters is one of the nicer side effects of the pandemic, and as I parked my truck and went to the meter on the mostly abandoned street I felt like kind of a sucker, wondering if the meter readers are even working their routes these days. But as I put the sticker on my windshield there under the shade of a sad little spreadsheet tree, I felt the talons combing my hair before I even heard the familiar squawk. I had parked right in the territory of a nesting pair of grackles, and they tag-teamed me with dive bomber runs all the way to the corner, more aggressively even than the red-winged blackbirds who were the nemesis of my youthful runs growing up in the Midwest.

We used to joke that Alex Jones is our spirit animal here in Austin, the one who replaced Willie Nelson after the pot ran out. But the grackle is our real spirit animal, especially as growth has pushed the armadillos to the margins. Grackles were the first birds I noticed when I took a new job here in the 90s and visited for a house-hunting weekend, with their crazy loud calls that sound like a radio being tuned with the volume all the way up. The long-tailed males whose dinosaur strut parades through every Saturday family lunch at the market, stealing french fries. The Biblical black flocks that descend on the shopping mall parking lots at twilight. One of those species peculiarly well-adapted to our urban environment, so well-adapted that when we give them a little room they take over like the cockroaches of the apocalypse.

In normal times, the city government and building owners dispatch armies of rangers and robots to haze the grackles back, shooting green lasers at the sidewalk trees at night and blasting the sounds of synthetic hawks from above the awnings. Of course the grackles are the ones who will rule the city when we are gone. They are an ingeniously opportunistic species, always dressed in black, and ready to own downtown.

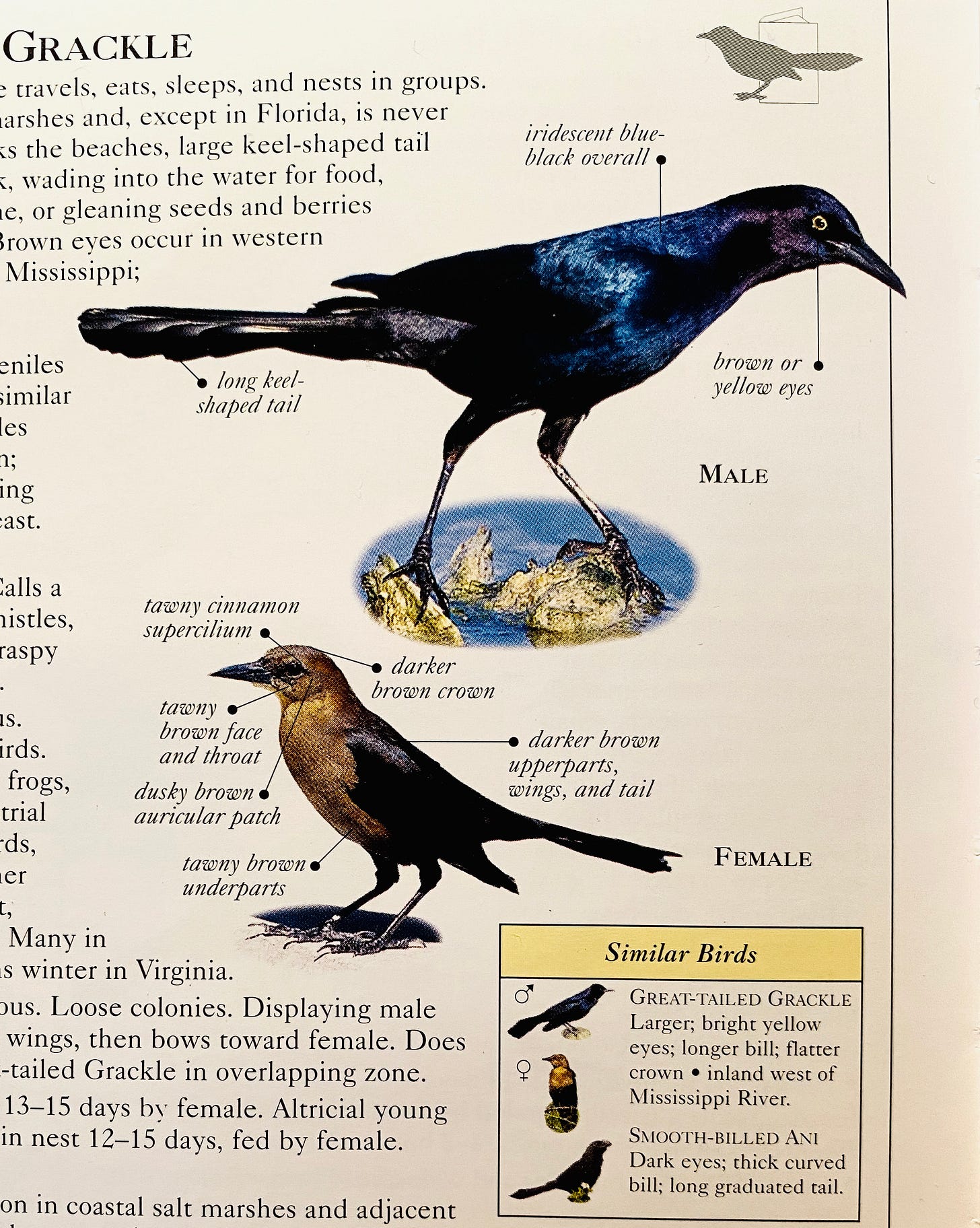

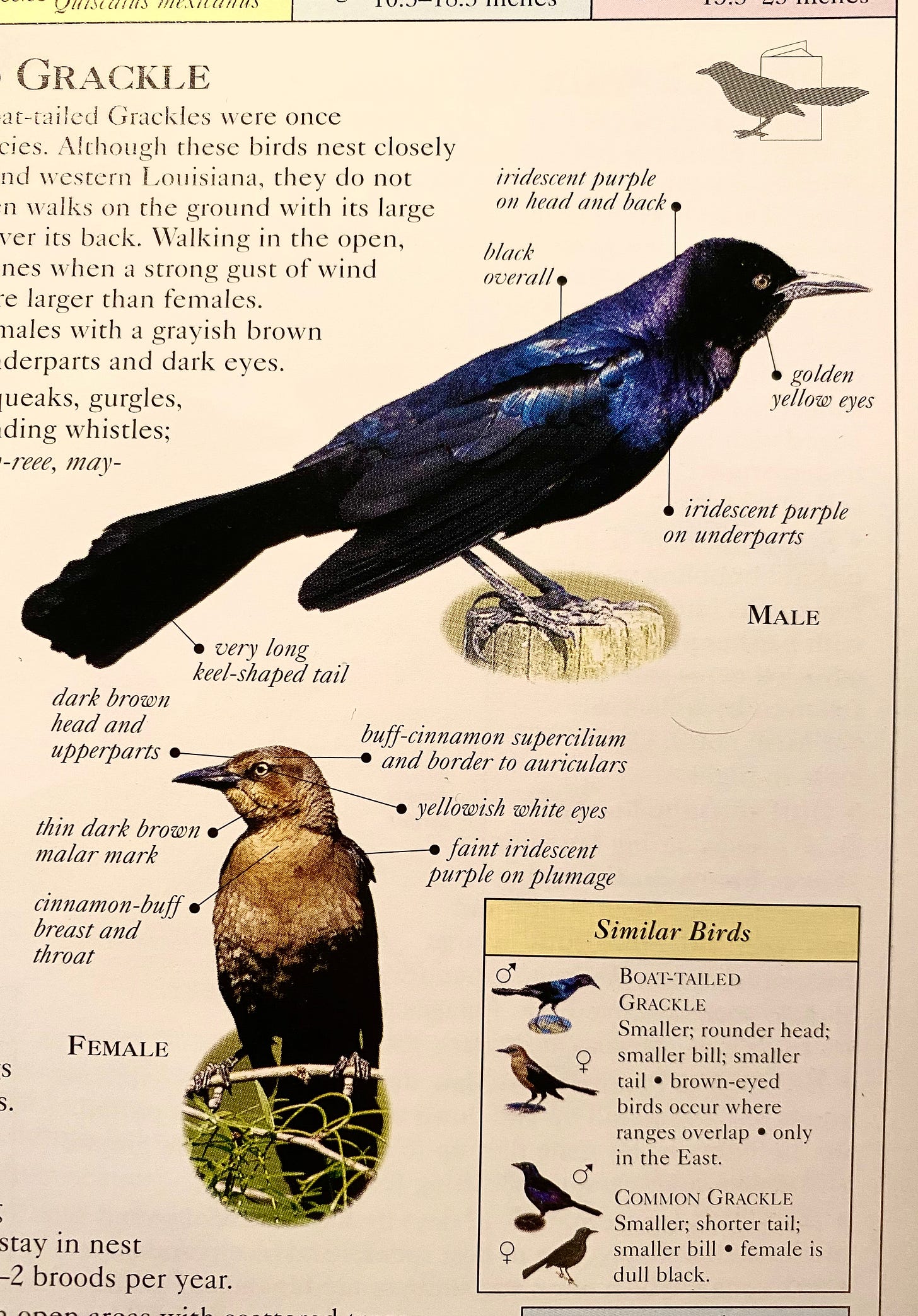

The bird books reveal several variants of Texas grackle: boat-tailed, great-tailed, common, and they are often found hanging out with another blackbird, the cowbird. The first two are the ones I am used to seeing around here, the ones the ornithologists consistently describe as gregarious, thieving, promiscuous, polygamous, noisy, and highly territorial. The males have a proclivity for insane competitive peacocking and even wrestling with their peers, even when there are no females around. They are basically omnivorous, and their flocks can number in the tens of thousands.

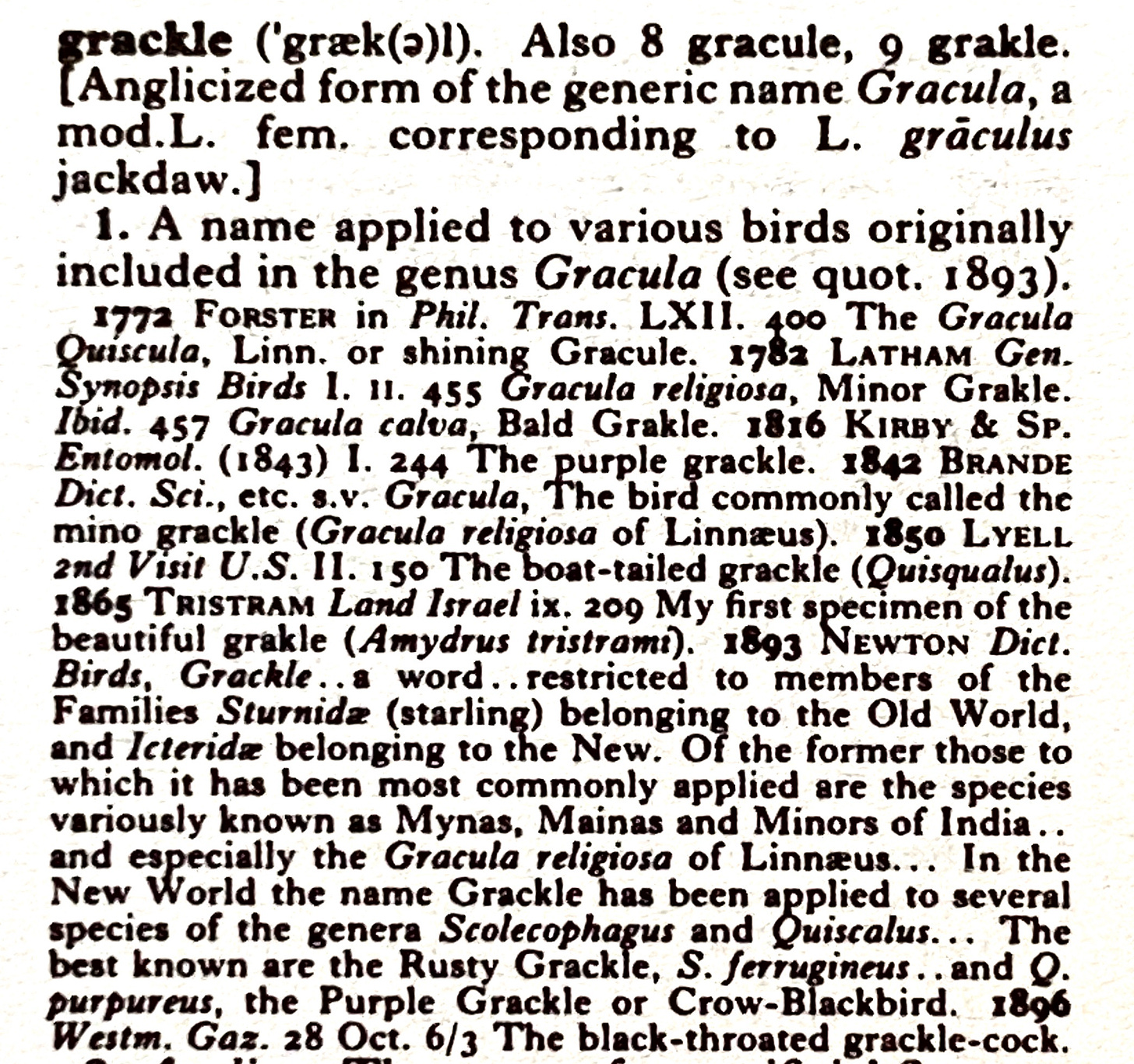

People used to call them jackdaws, after the Scottish crow “noted for its loquacity and thievish propensities,” according to the OED. The taxonomic name for the family is Gracula, evidently the Latin word for jackdaw, a word that would make an excellent Austin band name.

I was too busy running and ducking to get a good enough ID to determine which species of Gracula my attackers were, but when I stopped for a moment to grab some pebbles from the dirt at the base of one of those sidewalk trees, I spotted them up there in the landscaped terraces outside the southwest door, watching me like a little Hitchcockian gang. When I came back an hour later, they attacked me again, even managing to get my head a third time despite my knowing they were coming and thinking I had it handled.

A week earlier, The Birds had come on my parents’ TV as we were having an evening snack during our visit. It held up better than I remembered, with those scenes of children running from the playground as black birds peck at their heads and faces. The absence of explanation or scientific understanding is the real genius of that movie, and the way it riffs on our own animal sexual behaviors and territoriality as the real drivers.

The media has been rich these past weeks with stories of animals taking over cities as humans hide inside during quarantine. My thought when I read those stories is that in every instance, the animals must already be there—they just feel safer coming out in daylight hours now that our own nine-to-five hive has been suspended. Remember the story that North American beavers only became nocturnal after European trappers showed up? There’s a lesson in these stories about how the animals share our space with us every day, but manage to mostly evade our perception. The grackles, who never need to hide, reminded me how quickly some species will retake the social space we leave—and how effectively two little birds can be at hazing humans back.

This is the time of year when the retama are flush with their bright yellow blooms. The retama thrive around here, a perfect Texas edgeland tree that seems to handle most any soil type, grows fast and hardy with little need for water, and has wonderfully gnarly thorned branches. The yellow of its blossoms really glows in the light that shines in the wet weeks around the beginning of June. Too bad they don’t last longer—the flowers or the trees.

Baby and I walked down to the river Saturday morning, the first time in a couple of weeks. We have had nice storms lately, and the foliage along the river is super lush. Even as I laugh about grackles taking over from us, the native plants that have taken over the rocky beach near our place are the real deal, growing in what used to be a spot where they would dredge the gravel to build those streets and office towers. We’ve done a little bit of guerrilla gardening down there, and I like to think that has contributed to all the big switch grasses, but mostly I think it’s just the natural process of how the land and water heal on their own with a little time and inattention. The horsemint has bloomed late this season, at the same time as the blue sages that grow in the rock behind the button bush, splattering the banks in beautiful dollops of vibrant purple.

When baby woke from her morning nap, we walked our wild yard and inspected the diverse bugs that show up on the native flowers. Nature’s simpler wonders are best experienced from a toddler’s eye view.

I didn’t think to show her any of the Texas walking sticks copulating on our windows and doors, and she’s not old enough to understand how the diminutive males make the grackles look mellow, prolonging their coitus for days if not weeks in order to keep any other males from diluting their insemination. But I suspect they and the grackles will help me teach lessons about male behavior across species boundaries when she is a little older.

While baby and I were chilling inside our green bubble, mommy was downtown with a couple of our friends joining (at a social distance) in the protest outside police headquarters. The building is on the frontage road, and some of the protesters took the initiative to take over the upper deck of Interstate 35. They may not have even known the powerful symbolism involved, given that the freeway was constructed with its wall-like decks of concrete in order to reinforce the city’s principal line of housing segregation. But you can bet that history has a lot to do with the location of the fortress-like police station pictured below. As I wrote last week, I-35 is also the route of the main pioneer trails through these parts, a line through space that harbors a lot more natural history than you are likely to notice when you are stuck in its traffic.

Earlier in the week, a professor at American University remarked on Twitter that the week’s news provided another “eerie parallel” between contemporary reality and my 2017 novel Tropic of Kansas. Those kinds of congratulatory shout-outs for anticipating the imminent apocalypse always feel a little weird. As I have written elsewhere, when science fiction writers are seen as prescient, it’s usually not because they are good at predicting the future, but because they are accurately reporting on the present, through a kind of speculative realism. But I get it—I had been thinking the same thing that morning, even pulling my reading copy from my shelf to see if my descriptions of the political protests in Minneapolis that (spoiler alert) lead to a general uprising that overthrows a charismatic CEO turned fascist president matched up with the scenes in my news feed. The Gomi-no-Sensei’s aphorism that “the future’s already here, it’s just not evenly distributed” gets over-quoted (like I am doing right now) because it is true.

I will probably lose some subscribers for probing the edges of our insane contemporary politics in what was pitched as a weekly blast of diverting urban nature images, but to me urban ecology is an important key to understanding the deeper context of our headlines. The most valuable revelation I had writing Tropic of Kansas is the extent to which the injustices of our society are ultimately rooted in our damaged relationship with the land on which we live. The people and wild ecologies that were exterminated to bring the continent under plow and pasture, the slave economies that enabled the means of agricultural production, the wealth inequalities that inhere in economic systems founded on the extraction of surplus from the labor of others and the life essences of other species—our civilization is ultimately an elaborate system designed to control the reproduction of others (people, animals, and plants), and understanding that deeper history can provide useful perspective. A perspective that can help us imagine how else it could be.

For more on the boisterous wonders of American grackles, this National Geographic entry on Quiscalus mexicanus is a good basic reference starting point, this 2016 New York Times piece about a study of grackles so bold they would even drink the tequila at a Mexican restaurant is funny and illuminating, and this Texas Parks and Wildlife piece does a great job of explaining the quirks of their mating techniques.

For more on the out-of-balance ecology of human societies, I reiterate my recommendation earlier this year of James Scott’s 2017 book Against the Grain, which challenges the “standard civilizational narrative” by examining the origins of the earliest human settlements through a fresh prism, showing how the domestication and control of nature underlies most human power systems. If you want the Cliff’s Notes version, the Wikipedia entry is decent, the Guardian and New Yorker both have good reviews, and the London Review of Books piece is excellent (how I first learned of the book).

And if you live near a river or stream bank and want to help it look like those pictures above, check out Native American Seed’s riparian recovery mix for a jump start.

Have a safe week.