Rock, squirrels, paper

Plus: Empty Lots in the mailbox

Wednesday afternoon, running out to get a quick haircut around the corner from my office, I came upon a dead bird on the sidewalk. A fledgling, not yet feathered, the hairlike spikes of what would have become its feathers growing from grey-pink flesh. Its eyes were closed, in that way that makes death seem almost like sleep. Dead birds are a fairly common site on downtown streets, but I rarely give them much attention. This time, maybe because it was the anniversary of 9/11, I looked up to see where it had fallen from.

Sure enough, there was a nest. Or had been. There was a mama bird there, on an interior branch of the landscaper tree in the center of the photo above. A mourning dove, one of our most common year-round birds. What was left of the nest could be seen dangling beneath her pointed tail—a few curved bits of grass and twig. The rest, I saw, was there on the ground. The warm gusts of wind that blew through that corridor between high-rises explained the most likely cause. As did the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department’s online entry on the bird:

Mourning Doves tend to construct loose and flimsy nests. High winds and rainstorms often destroy many of them.

The week before, I had come upon three of the sturdier nests of the northern cardinals that live around our house. They had been constructed in the lattice of cross vine that hangs from our green roof over our living room windows, using a mix of dried grasses and twigs, and industrial materials harvested from the factories and warehouses that dominate our neighborhood.

There’s a whole subchapter in my new book coming out Tuesday, A Natural History of Empty Lots, about “The Architecture of Cardinals.” It describes the experience, over the course of many seasons here in our experimental house, of learning how well some birds have adapted to the anthropogenic opportunities of this edgeland corridor where factory meets forest.

The house, built in the ditch where a petroleum pipeline once ran, and then covered with a green roof comprised of seventy-some species of native grasses and wildflowers, functions a bit like an inverse terrarium, in which the humans are inside, watching the wild pageant unfolding through the glass. And every spring for the last dozen years, since the vines started growing down over the glass, some of the neighborhood cardinals have built their nests in those vines. We see them busily construct them, watch them tend and feed their progeny, and have even seen the fledglings take their first flight.

The nests don’t generally get re-used, and eventually they fall to the patio. That’s when you see that every single one of them includes layers of human-made synthetics, mostly packaging materials—fragments of open-cell foam, discarded food wrappers, bits of paper. Two of this season’s trio included long strands of the plastic backing from rolls of tape, printed with handy instructions that repeated over and over along the length of the ribbons embedded in the coiled mat of bird-manipulated grass:

REMOVE TO EXPOSE ADHESIVE

and, in the other one

PEEL AND SEAL WITH PRESSURE

The third nest included a crumpled clear plastic bag, the wrapper from a bag of crackers, and a weather-worn fragment of white plastic that contained, as the ironic legend for what had been repurposed as protection for newborn birds, the remainders of a warning from the manufacturer’s product liability mitigation department:

AWAY FROM BABIES

SUFFOCATION DO

CARRIAGES OR PLAY

As I note in the book, and have discussed here in earlier nest breakdowns, older bird guides sometimes remark how cardinals will use bits of cloth or string in their nests. I have yet to find a scholarly discussion of their use of industrial packaging, though there are fascinating papers out there on how house finches and sparrows in Mexico City use things like the fibers from cigarette butts, and the corvids of the Low Countries repurpose anti-bird spikes from building ledges as protection for their nests.

On a planet littered with plastic crap made by us, such weird and brutal yet beautiful adaptation should not surprise us. And it seems to be happening all around us in the urbanized natural fabric of everyday life—faster than scientists can keep up, but evident to anyone who learns to see it and pay attention to the little things the world reveals about how it is changing.

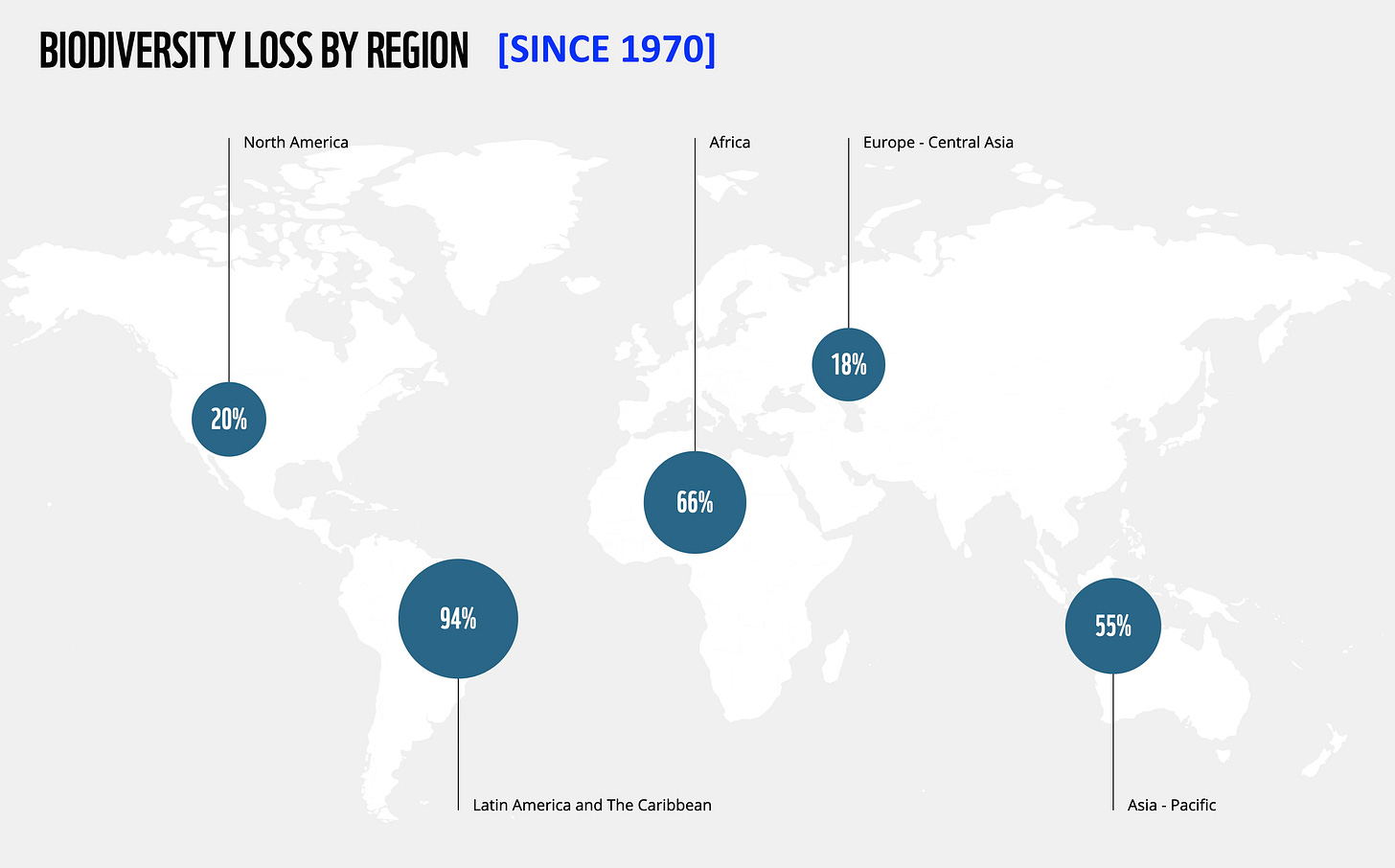

Thursday morning, working on an op-ed, I found myself looking up the source of a sobering statistic I quote at the beginning of the book: the World Wildlife Foundation’s estimate that the wildlife population of the planet has plummeted by 69% since 1970. That number was in WWF’s 2022 Living Planet Report, giving backup to changes many of us have sensed going on around us over the past few decades, with a number I haven’t been able to get out of my head since I first read it.

I hadn’t previously noted the geographic distribution of that loss, in a graphic that tells a deeper story about how tied up the ravishing of the planet is with Empire, Capital, and our insatiable appetite for surplus and ways to consume and accumulate ever more of it:

As the weekend arrived, pulling up to home, I found another sign of anthropogenic adaptation sitting right in our driveway. It was a Texas rock squirrel—a black-furred creature we had never seen around here until the summer of 2023, a native of West Texas and the Hill Country that can climb trees but prefers to burrow, and seems to be expanding its range to the east of the ecotone now known as the I-35 corridor. It stopped suddenly as it saw me step from my car, as if busted in the act of theft.

In its mouth was a huge clump of thin black plastic sheet, which it must have found there on the street behind the factories. Then it scurried off, to what I could now see was the spot where it had made its den—underneath the old shorty shipping container we use as our garden shed, a metal box with a plaque that records its history traveling the world with CSC during the Global War on Terror. The squirrel’s front door is the aperture in the steel designed to accept the blades of the forklift, and I couldn’t help but imagine the Anthropocene rodent home I would find if I could see inside there, like some cross between Beatrix Potter and H. R. Giger.

Our house and yard tries to achieve an increase in biodiversity, mainly through the re-introduction and cultivation of native plants allowed to grow wild. The appearance of new species is always a wonder, even when you worry their migration to here may be an indicator of habitat loss in their historic home. When you see how cleverly they are blurring the boundary between wild nature and human habitat, even as you are trying to do so by design from the other direction, it makes you wonder what other evolutionary frontiers will be breached as the animals adapt to and maybe even learn from us.

I found myself remembering the hilarious role-playing game I loved as a middle schooler at the end of the 70s, populated with mutant animals that had acquired the means of more effective resistance to our dominion:

When I researched the nesting habitats of mourning doves, the wildlife management bureaucrats included in their entry tips on how to build wire cone structures that will provide a superior foundation for the nests, especially in areas prone to high winds. I suppose that was targeted at dove hunters, and the flimsy quality of doves’ nests hasn’t prevented them from maintaining an abundant population—they are probably the most common bird in and around our urban woods. But the idea of using our tool-making ingenuity to enhance wildlife habitat instead of (or even in the aftermath of) destroying it is one we all need to start integrating into our lives.

A Natural History of Empty Lots

A Natural History of Empty Lots is my effort to synthesize the things I have learned in two decades of exploring the spaces where wild nature makes its home in the city, rewilding our own home and yard to provide a welcome for other life as part of our own, and working on ways to rewild the future, through the everyday work of local conservation advocacy, and loftier speculations on how to address the fundamental ecological imbalance built into the political economy of human civilization.

The book tries to tell truths about our environmental crisis from a fresh perspective, while also finding hope in the resilience of nature it witnesses, and helping us each find agency in building a future, with actionable tools for doing so without waiting for national and global institutions to act.

As narrative, it tries to mix the lyrical beauty and romance of nature writing with a clear-eyed witness of our post-industrial landscape, and to repurpose our paradigmatic stories of exploration, colonization and settlement in a way that might help us decolonize the future.

It will be released this Tuesday, September 17, by Timber Press, in hardcover and electronic editions that include photos by me throughout the text, and in an audio edition from Hachette Audio that I was lucky to get to narrate.

For an objective critical take, you can read the starred review in Booklist, and the complementary review in Kirkus.

For a more extensive authorial explanation of the book, you can check out the “Missing Introduction” I wrote here. And it’s not too late to preorder, including through this promotion on the Timber Press site that will continue until Tuesday

For those of you who kindly preordered already and told me you were interested, I finally got the print versions of the newsletter in the mail this week, and I hope you enjoy the supplementary material they provide.

In connection with the launch, in the weekend review of Saturday’s Toronto Globe and Mail, I had the fun opportunity to share some thoughts on back alleys, their human and natural history, and the potential for their revitalization as part of the interstitial commons.

And I had a blast talking with Boyce Upholt for his excellent newsletter, Southlands:

And if you are a subscriber to The Architect’s Newspaper, there’s an excerpt included in the print edition that just went out.

This week and next, I’ll be appearing at bookstores around Texas, and if you’re here/there and available I hope you’ll join us at one of these:

Wednesday, September 18, The Twig Bookshop, San Antonio, with Jennifer Bristol

Thursday, September 19, Book People, Austin, with Jesse Sublett

Thursday, September 26, The Wild Detectives, Dallas (Oak Cliff), with Bonnie Jo Stufflebeam

I’m also doing a bunch of radio and podcast interviews about the book over the coming weeks, and will have more bookstore and festival events later in the fall, which I will share here as the details settle.

Writing a book takes a lot of work, mostly for the reward of the enjoyment of that work, and the hope that it will reach and connect with others. If you read the book, and like it, please consider sharing, by whatever means you like. More importantly, if you find any of the book’s ideas about how to reconnect with and restore wild nature as actionable as they are intended to be, I hope you will give it a try.

Thanks for reading.

I’m intrigued by parallels between declining biodiversity that you highlight, and generative artificial intelligence’s tendency towards blandness, error, and sameness when its models are trained using data generated by the empire of AI. https://news.rice.edu/news/2024/breaking-mad-generative-ai-could-break-internet. It may lead to a doom loop of lack of diversity in thought and image in the content we consume. I hope we flesh and blood humans can continue to be as innovative, resourceful, and adaptable to the industrial and information changes we inflict on ourselves, as the birds you describe are, who find ways to use plastic to make a nest.

Congratulations on your book launch!