Rare beasts of the Anthropocene

Thursday morning I saw two men trying to rescue a beached Mercedes at the edge of town. They were on a sandbar in the Colorado, below the overpass that connects north Austin with the airport. You couldn’t tell how the car had gotten there, at least not from the vantage I had up there on the old bridge that has been repurposed for pedestrian and bicycle use. The only visible tracks were of the backhoe that had driven out there shortly before I showed up, and was now poking around in the sand trying to figure out a viable extraction strategy. You also couldn’t tell if one of the guys was the owner of the car, trying to mitigate the damages of a wild Wednesday night, or if they were just an enterprising pair practicing the long Texas tradition of taking whatever bounty nature offers, by whatever means available.

The field guides to the wildlife you can find on this surprisingly beautiful stretch of urban river never include the vintage cars one sometimes encounters. For many years there was a mid-60s Impala marooned in a nearby wetland, unmistakable to a kid who grew up when such cars were in wide circulation. Thursday’s Benz was a four-door, full size sedan, painted a yellow whose mottled mustard might have been a sun-baked relic of whatever brighter gloss rolled off the factory floor. I don’t know vintage Mercedes as well as I know old Chevys and Volkswagens, but I’d guess this was early 90s, maybe a 560SEL.

It was only when I looked at the photo I had taken on my phone that I noticed the white heron watching the scene, another species that’s hard to identify with precision, especially at that distance, but one that’s thankfully more common.

On Saturday mornings this summer I have been taking our three-year-old daughter to swim school. The school is in a suburban strip mall that also has a Half-Price Books, so after class we have been going there and foraging for interesting reads. Last week I picked up a very good copy of Peterson’s Field Guide to the Mammals, written by William H. Burt and illustrated by Richard P. Grossenheider—promising in the subtitle “Field marks of all species found north of the Mexican boundary.”

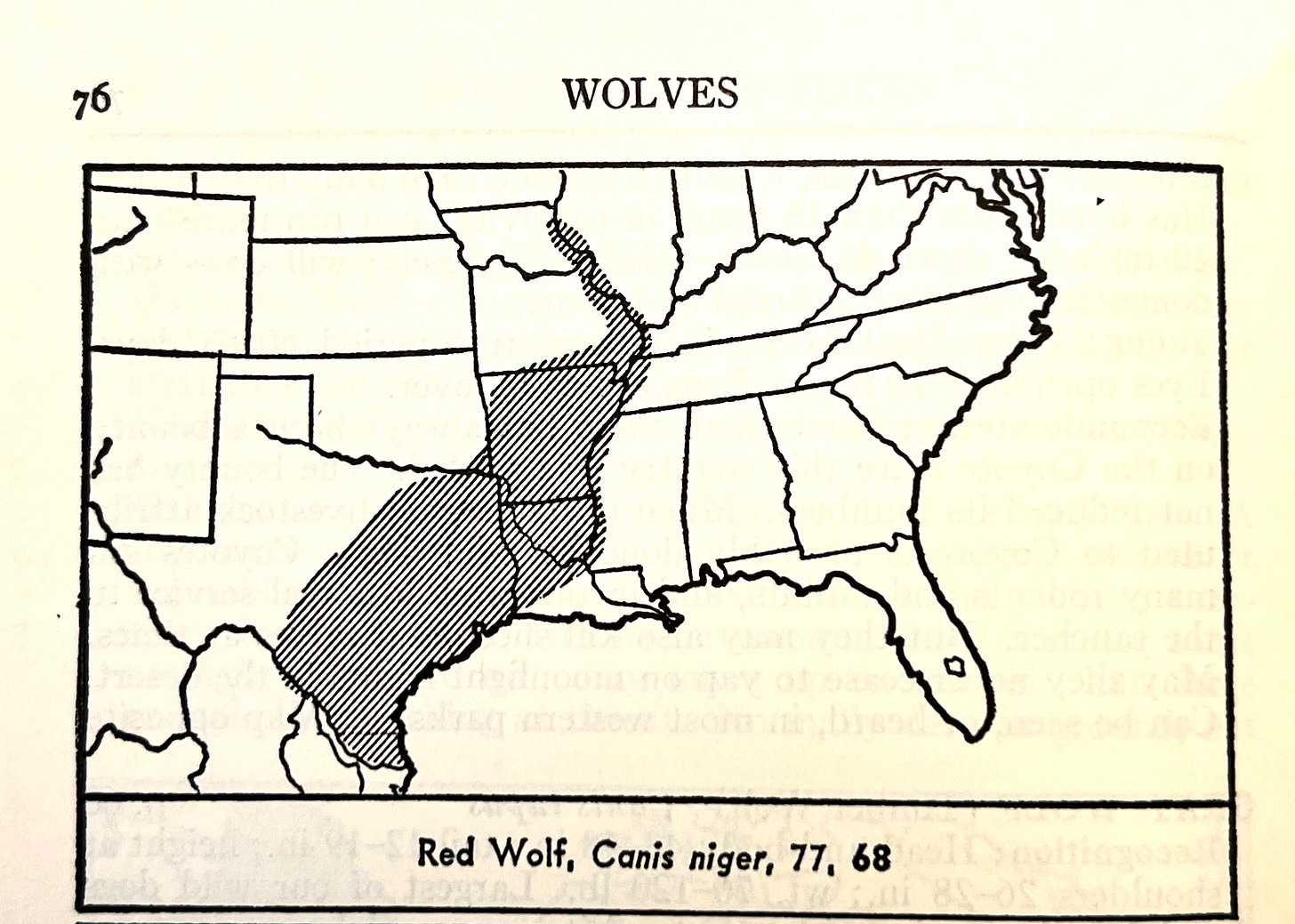

Sunday afternoon as we were hanging out at home I opened the book to the astonishing map pictured above, showing the range of the Red Wolf that once roamed widely across Texas, a creature now critically endangered. I hadn’t realized the species used to thrive as far north as St. Louis, and I wondered how old the book was that this could have been accurate. When I looked at the copyright page, I saw this edition had been published the year I was born, and the original edition the year my dad graduated from high school.

It made me wonder if some of the weird coyotes I have seen in the urban woods not far from that beached Mercedes might be part Red Wolf, after similar survival through interbreeding was documented in recent years in the edgelands of Galveston Island. Wishful thinking, no doubt, even as I can imagine the future when their descendants roam the ruins of Houston.

We do still see Bobcats once in a while, even if they don’t look much like this beautiful drawing by Mr. Grossenheider that illustrates the title page. Revised and Enlarged, indeed.

Here’s the real thing, on the prowl in the woods behind the industrial park we live next to, as captured on one of our trailcams in October 2020.

When my son was in first grade, early in the new millennium, we attended the first in what was then a new series of lectures for the general public curated by the natural sciences faculty of the University of Texas at Austin. The inaugural lecture was by Tim Rowe, the paleontologist who pioneered the use of magnetic resonance imaging to better understand the fossil record, thereby learning the deep connection between Cretaceous theropods and modern birds. He explained how the dinosaurs didn’t really become extinct—their descendants became the flightless birds of Oceania, who survived until the first humans showed up on those remote islands, delighted to find them populated with big fat creatures so unwary of predators you could walk right up and bonk them on the head. Only now, said the professor, in his lifetime, was the real extinction happening.

At the end he recommended one book, Paul Colinvaux’s Why Big Fierce Animals are Rare, a title that poses a question you immediately think you know the answer to.

Sunday I went for a seven-mile urban trail run while our daughter napped, navigating my way along train tracks and outlaw trails through the involuntary parks of East Austin. The air here seems nastier than it used to be. You could see it up on top of the ridge they call Red Bluff, an old dumpsite with an amazing view of the city wrapped in a low-lying ozone haze. Someone had left their cigarette lighter on a graffiti-covered table, ready for the next offering to the rain gods.

Back down in the floodplain I came upon a plastic prayer mat laid out at the spot where the trucks used to dredge gravel out of the river. Nearby, someone had left an empty twelve-pack of Freedom. And when I ran up on top of the berm, I found a tiny black and white textile fragment of the American flag, dropped by one of the urban nomads who walks the same paths I run.

On the home stretch, I came upon the remains of a turtle that had crawled up out of the river, only to be ground into an almost-unrecognizable form by whatever passing vehicle had run it over.

Maybe one of those ritual offerings my neighbors made in the secret woods did the trick. Thursday afternoon it rained for real for the first time all summer. A big but gentle storm that hung out in spurts through Friday night, giving Austin the long soaking it needed at the end of a brutal season.

Saturday morning the goldenrod and sawtooth sunflower that looked dead the day before were perked up with the promise of fall flowers. The first migrating butterflies showed up, and I started finding flying ants on my sleeves. At sunup I set out to soak up the woods as it cleared up. As I was getting my boots on, our daughter emerged from the bedroom, a little earlier than usual, as if she knew. I persuaded her to wear some long pants under her hand-me-down Ice Princess dress, and come along for a ride in the backpack child carrier that we hadn’t used in a while.

All summer long, despite the drought, the Lower Colorado River Authority has been releasing water from the dams upriver, supposedly to supply agricultural irrigation downriver. The releases have been in the early morning, meaning the urban river is flooded as soon as the sun comes up. This week the releases finally stopped, and we could walk in the shallows of a river that feels more like its natural self. The favorability of the conditions was confirmed by egrets and herons, green, white and blue, the half-dozen turtles who poked up their heads to look as we emerged from the woods, and by the fish sign in the current.

We didn’t get very far, until the Ice Princess decided it was time to turn back, right after we got done counting the three caracara that flew over right where the river widens. We admired this tire working its way back into the earth. And then I got her agreement to walk back through the dark woods instead of the tamer path we had taken.

On the street where we live, all the manhole covers above the storm sewers are marked with pictures of fish and the reminder “DRAINS TO RIVER.” Those drains were all drying out by the time we got there, but walking back home in the woods you could see all the fresh trash they had brought in the night. Styrofoam cups, plastic bottles, big sheets of industrial packaging, and all the other things left outside to be washed away. You get used to it, surprisingly quickly, as you immediately see how Sisyphean the idea of any real clean-up is, without changing the system that generates that waste, as the world burns.

As we headed home, walking carefully to avoid tripping over any of the trash or tree fall that littered the forest floor and bringing our Master/Blaster set up crashing to the ground, we came upon a little grove where the tall cottonwoods and sycamores surround a spot that would make a great campsite. There’s a white plastic pylon back in there, almost as tall as me, that once marked the swim area of some highland lake. As we passed through the far edge of it, the morning sun was casting its rays through the canopy. Almost corny in its greeting card evocation of the divine, but a welcome reminder, both of the persistent possibility of reprieve, and the certainty that the summer sun will never really go away.

Further reading

Here’s the full Bobcat video, which gives a much better sense of the animal than a grainy photo:

This NYT piece on “The Ghost Wolves of Galveston Island,” which I shared earlier in the year and linked above, is really an amazing story of how threatened species adapt in the margins of our erasure of the wild.

For some interesting musings on the coloration of herons and egrets, check out this interesting piece by Bill Reiner at Travis Audubon.

For a fuller story about that drowned Impala, check out this 2013 ode, “Requiem for a Muscle Car,” from my old Tumblr. The piece is kind of the first of these urban nature notes I wrote, and I have just repurposed it as the opening of the book I am working on with this material.

For a great natural history adventure story, check out Michael Novacek’s Dinosaurs of the Flaming Cliffs, which includes some nice passages about Professor Rowe’s work.

And speaking of flying ants, all of the new subscribers who have been finding their way here probably missed my June 2020 report on the nuptial flight of the fire ants, which remains the most widely read piece here so far.

Field Notes will be off the next two weeks, as I will be in the field looking for some different rivers and older forests. Stay cool at summer’s end, and look for the next report after Labor Day.

Thanks for another interesting Field Notes. I enjoy the Mercedes story as well as the sightings of wildlife and habitat. Thank you, Martha Richardson

Well written, an easy read. Telling "after the rainfall" photos. Good to learn your drought was finally broken. Expecting more rain to come on the front edge of the tropical storm?