Skull season

And some book news (No. 191)

One morning last week, our year-old Jack Russell Terrier and I found three skulls in the weird woods behind our house. Fifi (so named by our six-year-old daughter) found two of them, proving herself a more capable field companion than I had expected from her homuncular scale. The most remarkable of these totems was the stag pictured above, which she found a few feet away from the carcass I had stumbled upon; the opossum she found still attached to its spine was also pretty intense. The doe skull had been out there for years, evident from rain-bleached white bone. We did not take them as omens; just signs of the season, when the foliage is at its barest, animal trails are easier to follow for the bushwhacker, and things are easier to spot when you do. In a couple of weeks it will be over—the invasive brome grass is already beginning to carpet the forest floor, crowding out the natives by coming up before them, and the spiderwort came back strong this week, flourishing in the dirty soil of ancient bluffs polluted with illegally dumped construction debris slowly sinking into some Anthropocene geological layer.

It’s good to know the coyotes are still around, after a few seasons where I worried they had moved on. The pandemic brought a lot more people into this pocket of riparian forest down between the dam and the bridge, and the human activity on the upland terraces around it has gotten a lot more intense. If you drive up the onramp to head south on the old highway, you get a glimpse from above of the Saruman-grade hole they are digging to house the pump station that will channel all the runoff from expanded Interstate 35 into the river, and at night you can see the lights of the crews working under the Moon. I have not yet seen any orcs being hatched, but they do have Skylink.

The naturally-occurring folk horror of the urban woods is an addicting thing. Experienced through regular ambles over the course of multiple seasons, it reveals the story of the food chain in the land, both the nibbling of the peaceful foragers and the left-behinds of the predatory hunters, and the ways that the other species we share the world with are left to occupy the margins of our dominion. Winter’s end lays it bare, when you can see not just every bone that would otherwise be buried in the tall grass, but also every nugget of the unimaginable volume of human trash the floodwaters leave behind.

February in this mostly unfrozen climate also brings the first signs of spring—not just the brome and the spiderwort, but also the rosettes of the native wildflowers that somehow persist even more resiliently than the coyotes and the whitetail. I saw the first bluebonnet blossom of the year Thursday, at the edge of the parking lot of our daughter’s school, and the rocky riverbank behind our home is flush with plants a couple of weeks from blooming.

The most beautiful seasonal development for us this winter’s end is probably the two mated pairs of great blue herons that have nested in a tall sycamore down in the floodplain right behind our house. There have been a half-dozen nests in another such tree upriver a bit for at least the last 7-8 years—I devoted a subchapter to it in Empty Lots—but last year was the first such nest visible from our living room. After many of the big floodplain trees were uprooted from their boggy basin by the 85-mph microburst that inaugurated last summer, I feared they would not come. So to see two nests where last year was one is an especially uplifting thing. The herons are an ambient presence all through the day, moving back and forth across the widescreen of our windows as we are making coffee, gathering more nest-making materials and skronking in the wind as we wash dishes and host friends, always with that lanky, extra-large grace that reminds you how close they are to the pterosaurs.

Even an old cynic like me feels the simple wonder and romantic sense of hope such a witness kindles, of a majestic species that a century ago had almost been extinguished now thriving within earshot of a door factory and a bus depot. A little research reveals how common such adaptations are all over the country, as various species of herons and egrets have learned how to make their nests in the interstitial remnants of viable habitat we have left them in otherwise intensely industrialized zones, from Newark Bay to the suburban delta around DFW Airport. When you learn that a healthy heronry involves a colony of as many as five-hundred nests, the hope and wonder sobers up a bit, as you wonder if any such colony could still be found.

The Sunday before last I attended the beautiful and uplifting memorial of my neighbor, friend and ally Daniel Llanes, a singular figure I got to work with for fifteen years advocating for these pockets of urban wild. I was feeling upbeat as I drove home, impressed by the diversity of the folks that turned out to laugh, cry, shout, and get re-energized about the power of community to make change happen. As I rolled down our street, passing Daniel’s home he made from an old auto body shop across from a truck tarp shop, I saw a weird jumbo jet coming in heavy, on final approach to our local airport. It was painted with the colors of some unknown airline, blue on white with the name “NATIONAL” painted across the fuselage.

I looked it up on the planespotter app, which lets you identify aircraft from their proximity to your location. An Airbus A330-200 operated by National Airlines, which research revealed is a private charter that specializes in defense logistics, “moving sensitive, high-value, and highly classified cargo to the world’s most complex locations.” It was arriving from Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas, after having flown there earlier that morning from El Paso, and was scheduled to leave two hours later for its corporate home base in Orlando. I wondered what cargo it carried, and what kind of border-forward operations it was supporting. I even wondered if the windowless plane might be loaded with people, in this era when “Homeland Security” officials talk up their ambition to be like “Amazon Prime, but with human beings.”

Two mornings later, the insane news alert came out at the beginning of the work day that the airspace over El Paso had been closed for 10 days for undisclosed emergency reasons. The closure was reversed later the same morning, and various fragmentary pseudo-explanations about drones and counter-drones were circulated. I wondered if the plane I had seen had some connection to whatever’s going on out there, and to the other news reports about the massive detention facilities now being operated on the grounds of Fort Bliss. (My wife posed the question whether it might be evidence from the Epstein ranch being moved to a more undiscoverable secret location.) I found myself thinking about how, since the huge deportation funding bill was enacted last summer, the skies around here have become more active with all manner of unexplained military and paramilitary movements, in a way I haven’t seen since the tail end of the War on Terror, when we first started living under the flightpath. How the vibe back then, which was also the aftermath of the Financial Crisis, the peak of #Occupy, and the long year of the Arab Spring, induced me to write black mirror fictions imagining what it would be like if that war, with its black sites and extrajudicial punishments, came home.

That era, the last few years of the Obama administration, was also when we seemed to be trying to take on more robust public policy efforts to tackle the climate crisis. This week I read most of the EPA’s final rule rescinding the 2009 finding that greenhouse gas emissions endanger clean air and human health, curious to see if it would provide any insights into what all is going on in the hive mind of the state. The document endeavors to ground its decision in dry questions of statutory authority, but the exuberant celebration of extractionist restoration comes through. A reminder that the war on nature and the war on our neighbors are deeply connected, and the path to a better future starts with seeing those intersections more clearly.

New Book News

I’m delighted to share this deal report from Thursday’s edition of Publisher’s Marketplace:

The aim of this new book is to blend nature writing, technology criticism and memoir to explore the landscapes of 21st century capitalism through a natural history prism, seeking out pockets of biodiversity and adaptation at a moment when machine intelligence seems on the verge of taking over the world, and exploring paths to a greener and more livable future. It will be centered on field visits to sites that epitomize our current economic and ecological trajectories, and I am excited to dig into that original research around the continent. I may be pinging some of you for help and local knowledge.

Thanks to all the readers who checked out and spread the word about A Natural History of Empty Lots (the ebook edition of which is still on sale as of this morning), and this newsletter, and helped create the opportunity for this new book.

Let’s Go for a Walk

I’m also really excited about this upcoming event announced Tuesday, the first-ever collaboration between the Texas Book Festival and Fusebox, our amazing local performing arts festival. Unfortunately, all the tickets sold within a day! So if you are in Austin and want to go for a walk but didn't get this news in time, feel free to email me and we’ll work on one just for readers of this newsletter.

The Roundup

Happy 94th birthday to Gerhard Richter, whose landscape paintings have been on my mind of late.

On the subject of the “endangerment finding,” I was simultaneously uplifted and sobered by Bill McKibben’s newsletter this week about the coming El Niño, and how it’s arrival will quickly bring the urgency of the climate crisis back to the forefront of our politics.

The February issue of Harper’s has a great Hari Kunzru piece on his psychogeographical ramble through “Another London.”

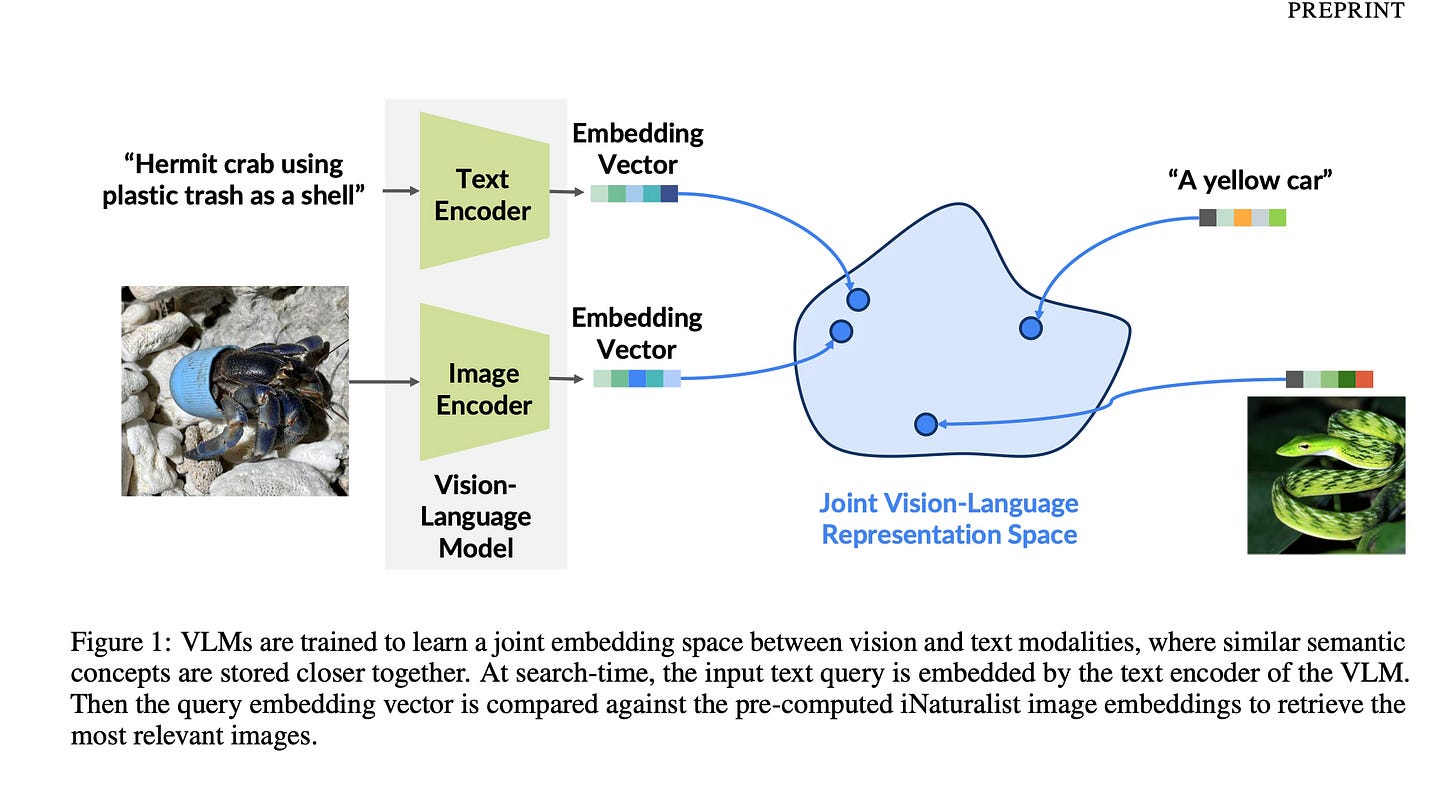

Thanks to Field Notes friend and “human web-crawler” Bruce Sterling for this amazing piece on how to use deep search to find novel Anthropocene nature adaptations in crowdsourced digital platforms, or “INQUIRE-Search: Interactive Discovery in Large-Scale Biodiversity Databases.” An outtake:

RIP Jesse Jackson, who I got to meet in Chicago in the summer of 1985, after experiencing an amazing morning session at PUSH headquarters, an old South Side synagogue that had been turned into the venue for rousing secular sermons. My Republican parents had been so moved by his message that they crossed over, supported him in the 1984 Iowa Caucuses, and hosted one of his senior staffers in our Des Moines home. He was perhaps the most effective orator I ever heard, and definitely the most grounded in a righteous sense of justice. Over at Grist, a perspective on his commitment to environment justice.

In urban wildlife news, interesting New York Times report this week on the cougars of L.A. and the wildlife crossing that’s about to open just for them.

Longtime readers of this newsletter know that cavorting between black vultures and crested caracara is not as surprising as the Times suggested in the same issue of Science Times.

Have a great week.

Picturesque and peaceful. Then compelling and prompting to action. Then frightening and flight-inducing. You cover a lot of ground. But a really good summary of and commentary on What’s Going On. Love the nature photos!