Rain lilies and robots

No. 140

September finally brought us some rain here in Austin, the first since June, unless you count the 0.16 inches of July 6 and the 0.14 of August 22, amounts recorded on the official charts but not in our memory. It was one of those summers where you began to wonder if it would ever rain again, and when it finally did, it poured on and off for more than a day. Most of it on the day consecrated to Thor, which also brought the new moon. You can feel the connections, even if you are not permitted to suggest they are real.

I had almost forgotten about the existence of rain lilies until a week later, when they appeared here and there across the browned land, little eruptions of fresh native life in the dried-out expanses of ornamental grasses that cover the unpaved parts of this city that once was prairie. I first saw them at the base of the onramp near our house. That afternoon, driving back from lunch with a friend, I saw them all over, mostly in the slivers of dirt left between the sidewalks and the curbs of major roads.

It took me a long time to learn to notice these plants. While they tend to grow in dense patches, they are individually small, and intrinsically ephemeral, only ever appearing a few days after a good rain, then drying out and disappearing a few days later. You have to get down close to them, on foot, to really witness the beauty of their pink-to-white blossoms. And you have to notice them over long expanses of time, years in my case, before you appreciate their embodiment of the way the rain immediately brings back the life in this hot, dry region. When they appear in dirt you recently saw the bulldozers terraform into the platform for a new overpass, you realize the resilience they evidence, always reappearing in the landscape of our erasure.

The pioneers called these flowers the evening star, for their nighttime bloom, and perhaps for the way they are not as bright as the others, but a consistent indicator about where you are in the season. The revelation that they are pollinated by sphinx moths and other night flyers confirms their proximity to the world of faerie, as I tried to convince my four-year-old daughter when we walked to see the last few blooms as the trucks blew by.

Harder to explain is the way the rain lilies only respond to rain, not to water from a hose or sprinkler. How do they know, and why do they care?

By the equinox, they were all gone. And the next day, Yom Kippur, brought more precipitation, with intense lightning in every direction and hail as big as your fist. A little north of us, the icy deluge at the end of a ninety-five degree day was powerful enough to shatter windshields, destroying most of the inventory of several suburban car dealerships. A suitably Old Testament message from above on the barely observed Day of Atonement.

My brother-in-law reported to me later that he had been out in his canoe during the storm, scouting downriver for the alligators rumored to have moved into these parts. That night he had skipped family dinner, texting me to send him the photo of alligator tracks I had found in the riparian edgelands behind the dairy plant six years ago. He returned the favor Wednesday morning, with this shot of a spectral urban coyote sauntering through a residential section of East Austin before dawn.

When the shortening day dials up and the coyotes mostly disappear, the robots come out. The self-driving Fords seem to have moved on, but robot Volkswagen vans have replaced them, cruising up and down the main road that connects the airport highway to downtown. I wonder what new German words they will teach us. And whether, like the protagonist of Radio On, the amazing Chris Petit road movie I watched on Criterion last weekend, they listen to Kraftwerk.

As they await their redevelopment into the new urbanist wonderlands you know are on the drawing boards, many of the expansive old industrial lots in our neighborhood have been taken over by robot training facilities. The VWs come and go from what was, a few years ago, a plumbing supply wholesaler, until it turned into a stable for the nine-eyed Argos Ford was training to repossess themselves until Detroit shut down the venture this spring. And right around Labor Day, the old AT&T maintenance yard across the street got gussied up, with armies of dudes out there in the morning power-washing the pavement and mowing back the weeds. I figured they were getting ready to break ground on an office tower, but instead they put down new blacktop, screened the chainlink with black tarp to hide their operations from your view, and trucked in giant charging stations for the self-driving taxis now permitted to take you across town.

I suppose they needed the fresh asphalt so the new paint stripes would be more legible to the LIDAR, a revelation that may be the first time I have applied my capabilities as an animal tracker to the robots of the urban trail. And then you wonder whether they can plug themselves in yet.

When they cleaned up the lot, they left the old utility pole obstacle course at the southeast corner, where the trainee linemen used to learn to climb. In the years of its abandonment, that stand of tall, embalmed pines had begun to acquire the totemic energy of some enigmatic henge. I wonder if the carbots can see it. In time, perhaps they will adopt it as their sacred grove, the embalmed trees that embody connection to the network.

The Friday before the equinox, I stopped by the downtown library to borrow a copy of Stephanie McCarter’s new (2022) translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, seeking its retelling of the myth of Erysichthon, the vain aristo who defiled the sacred grove of Demeter (Ceres in Ovid’s Latin version). Seeking lumber for the party barn he wanted to build, Erysichthon led his crew to harvest a divine tree that measured fifteen dryad wingspans around. As his ax struck, the screams of the nymph within could be heard. Upon hearing the news from the other dryads, the goddess of agriculture cursed Erysichthon with a hunger he could not sate until he began to eat his own flesh.

I’ve read various versions of that tale in recent years, and many other stories of sacred groves, seeking deeper understanding of the idea of the place in nature that embodies the divine, and our connection with both, an idea whose echoes are all over the place but the original expression of which has the elusiveness of the truly ancient. McCarter’s Ovid is the first time I’ve picked up an alternate reading of the story, embedded in the poet’s finger-wagging description of Erysichthon as one who “spurned the gods and burned no incense upon their altars.” It situates the defiler as a free-thinking liberal who denies the existence of imaginary deities and embraces the instrumentalism that is his nature, while revealing a religious fundamentalism in the teller of the tale. Erysichthon’s dominionist hubris may be how we got to this climate juncture, but the path out of our mess is not backwards. It’s some yet-undiscovered third way that rides the dipole between animism and reason. Learning to perceive nature without objectifying it, while at the same time learning to truly live in it.

There was a lot of alarm in my feed from writer friends this week, following The Atlantic’s publication of a piece about how 183,000 books have been used by Meta and others to train large language model AIs. Out of a mix of curiosity and vanity, I put my name in the search, and sure enough, two of my novels were on there. My reaction was not the outrage I had been encouraged to feel by my fellows, but more like a shrug. Maybe because, as I understand it, they are not storing the texts, but just reading them, in order to learn, the same way we do. (The article was behind a paywall, so I may just be ignorant of the whole story.) My experience of the laughable economics of book publishing, something writers rarely reveal, may also be a factor. Of course, the cheapening of the value of books is very much attributable to the disruption wrought by machine intelligences. On the pavement of the former truck dealership next to the Cruise charging station, they train new Amazon drivers how to deliver things cheaper and faster, probably by using machine metrics to make those human drivers cheaper and faster themselves, to extract as much profit as possible until the trucks are ready to drive themselves.

Seeing those freshly painted lines on brand new blacktop designed to make it easy for our newly autonomous cars to find their way home, I can’t help but imagine how Capital will now get to work to write over the surface of the world so it can be navigated more easily by robots—on the ground, in the air, who knows where else. I think of all the things our smart machines cannot perceive, like the beauty of Jupiter and the full Moon shining in the early morning sky this weekend, or the almost-unexplainable weirdness I witnessed the morning after the hailstorm of an armadillo butt emerging from the ground, stuck in the green plastic PVC vent it had dived into to escape the lightning.

As this dystopian century plays out around us, I wonder if the newborn machine intelligences of our sci-fi nightmares might, by their very existence, help us learn to better see the real world the city hides from our perception—all the things in nature that Capital and its instruments do not see. I have seen this movie enough times to know better than to hope for a technology that is not totally captured by commerce. But maybe, in its protean weirdness, the way it expresses some strange, unhinged messages from our collective consciousness, we might find that our conversations with it help us find our own way to the other side. Or at least see things from a fresh perspective, the way a new translation can open up your mind to the inversion you need. Assuming the bots will be working for us, and not the other way around.

Reading list

Stephanie McCarter’s Ovid is just one of the fresh takes on canonical Classics that have hit the shelves in recent years, many of them by women. The September 11 New Yorker had a fascinating profile of Emily Wilson, whose refreshing translation of The Odyssey I’ve been reading over the summer, and whose new translation of The Iliad came out this week. The piece, by Judith Therman, does an especially great job of connecting those ancient works to our contemporary crisis, in a casual but profound way.

On NPR last week, I caught a fragment of a fascinating broadcast on the history of Tenochtitlan, which got me to look up the full episode, and to track down the book it drew from, Tulane art historian Barbara Mundy’s The Death of Aztec Tenochtitlan, which revises the conventional wisdom about the conquest with insights from art history and Nahuatl texts recorded by early missionaries but never translated due to the uncomfortable truths they told. For those of us who live in this colonized space, and have some capacity to see how that heritage is not entirely erased from our social and ecological environment, this seems like essential material.

Thanks to my friend and occasional lunchmate James Foster for loaning me his copy of the August 18 issue of the Times Literary Supplement, which had a review of three interesting new books about the urban wild released this summer: Wild City by Florence Wilkinson, Urban Jungle by Ben Wilson, and Secret Life of the City by Hanna Bjørgaas. I had already come across these books, and read from two of them, but I had missed the TLS roundup, even though that issue was in a stack of my own accumulated summer mail.

While I was happy to see the coverage of this topic, I was disappointed in the review by Richard Sennett, an urbanist affiliated with the Columbia University Center on Capitalism and Society, who was reflexively dismissive, in a very uptown way, of these books’ advocacy for the possibility of the rewilded city. Sennett is right to be wary of the Romantic restorationist impulse, and to counter utopian visions with sober realism about our climate trajectory. But he misses the way these books, and the works they document, urge us to think about the urban environment in a fundamentally different way—learning to really see the other life around us, as a step toward obliterating the illusory distinctions between nature and human habitat the city wants us to believe in.

The Washington Post ran a remarkable profile on September 13 by Maura Judkis and Jabin Botsford about an unusually savage new pastime for such a buttoned-up city: taking pet terriers out into the streets and alleys of Adams Morgan at night to rediscover their and our predatory natures, hunting rats. The story bites into the material with a lot of insight, embedding a Ballardian narrative of townhouse dwellers gone wild, embracing the violence of their own humanity in a way that is transgressively honest, and witnessing the ways that our dogs are vicious embodiments of that violence, bred by us over centuries to be the instruments of our predation.

And in the not as open spaces as you think department, this week’s NYT had a great piece by Michelle Nijhuis advocating the replacement of barbed wire with electronic fencing in the rangelands of the American West. Nijhuis’ 2021 book Beloved Beasts, a critical history of our learning to perceive and try to prevent the extinction of other species, is a great read.

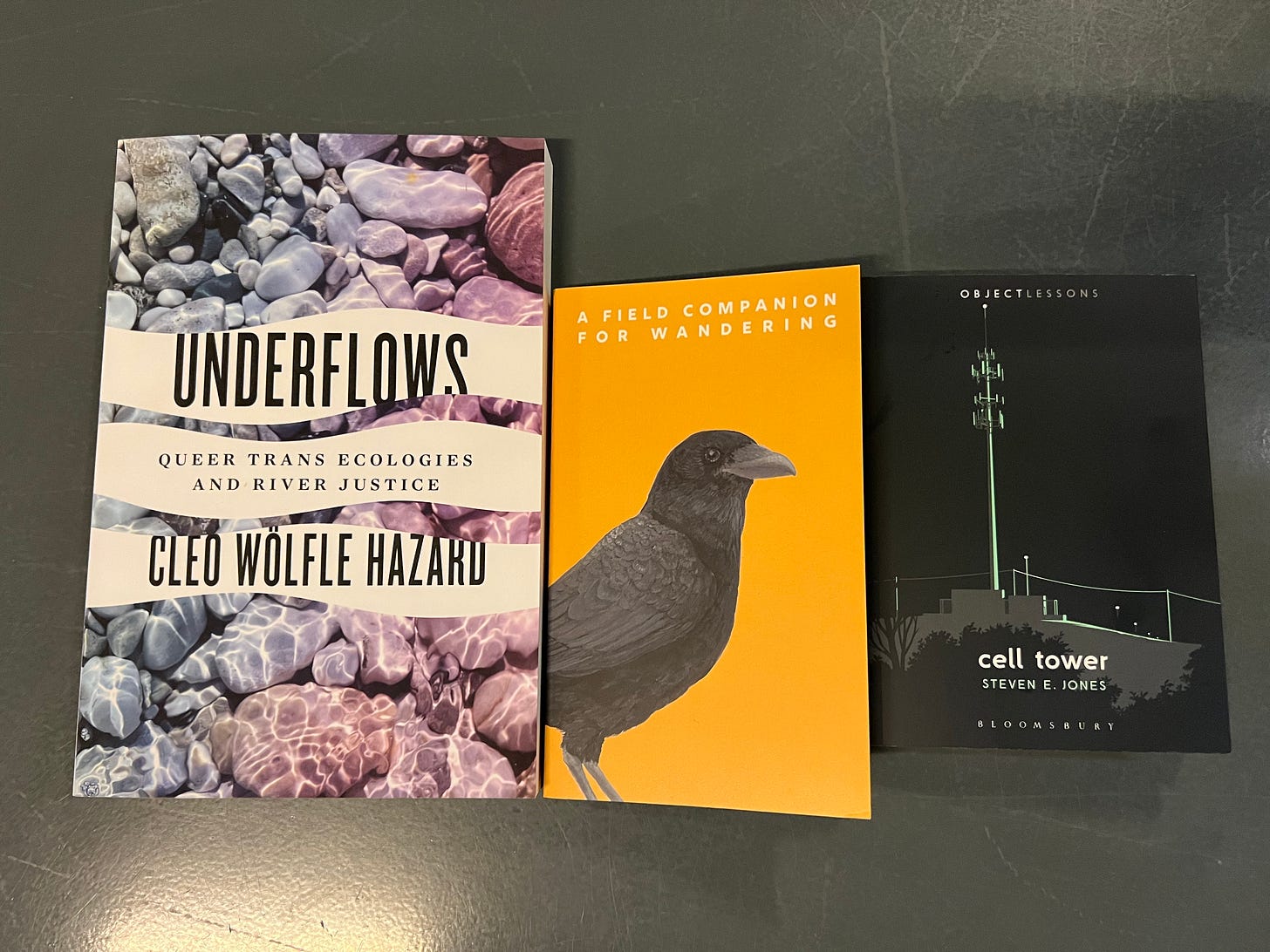

And if you’re in Austin and interested in some fresh reading, please stop by Alienated Majesty, the incredible new bookstore that just opened in the space formerly occupied by Malvern Books on 29th St. The curation is incredible, including the finest selection of books on nature & environment I have ever encountered (my first small haul pictured above). My friend Joe Bratcher, who founded Malvern ten years ago and died last year due to complications of Covid, would surely be happy to see the fresh direction his legacy has been taken.

Welcome October, and the beginnings of real autumn, and have a great week.

The bedside reading list grows and grows. Thanks for this fine and welcome Sunday read. I'm actually in Adams Morgan for work. There is a fine book store there where I came across a new author (for me) named Tom Cox. MacFarlane raves about him. Check him out!

That armadillo will be replaced by a more efficient robot. If they ever make robot cars that can't be befuddled by traffic cones...

I loved Wilson's Odyssey and must get her Iliad translation. McCarter's Ovid is beside me on my chair.

It's fascinating, that the evening star flowers know rain from sprinklers. I wonder if they would like water from a rain barrel...