Pink Moon, Brown Earth, Rebirth

No. 177

The almanac writers, who work hard to turn your desire to see the full moon into a compulsion to click through to their site and pass your eyeballs over their ads, label April’s orb as the Pink Moon. The truth is it’s not pink at all, and it’s not even that remarkable as moons go, because it’s as far as it gets from us. But there are a lot of things the algorithms don’t bother to mention, like how they determined which sports team tattoos license Border Patrol brownshirts to disappear you, or the fact that this year Easter falls on Hitler’s birthday.

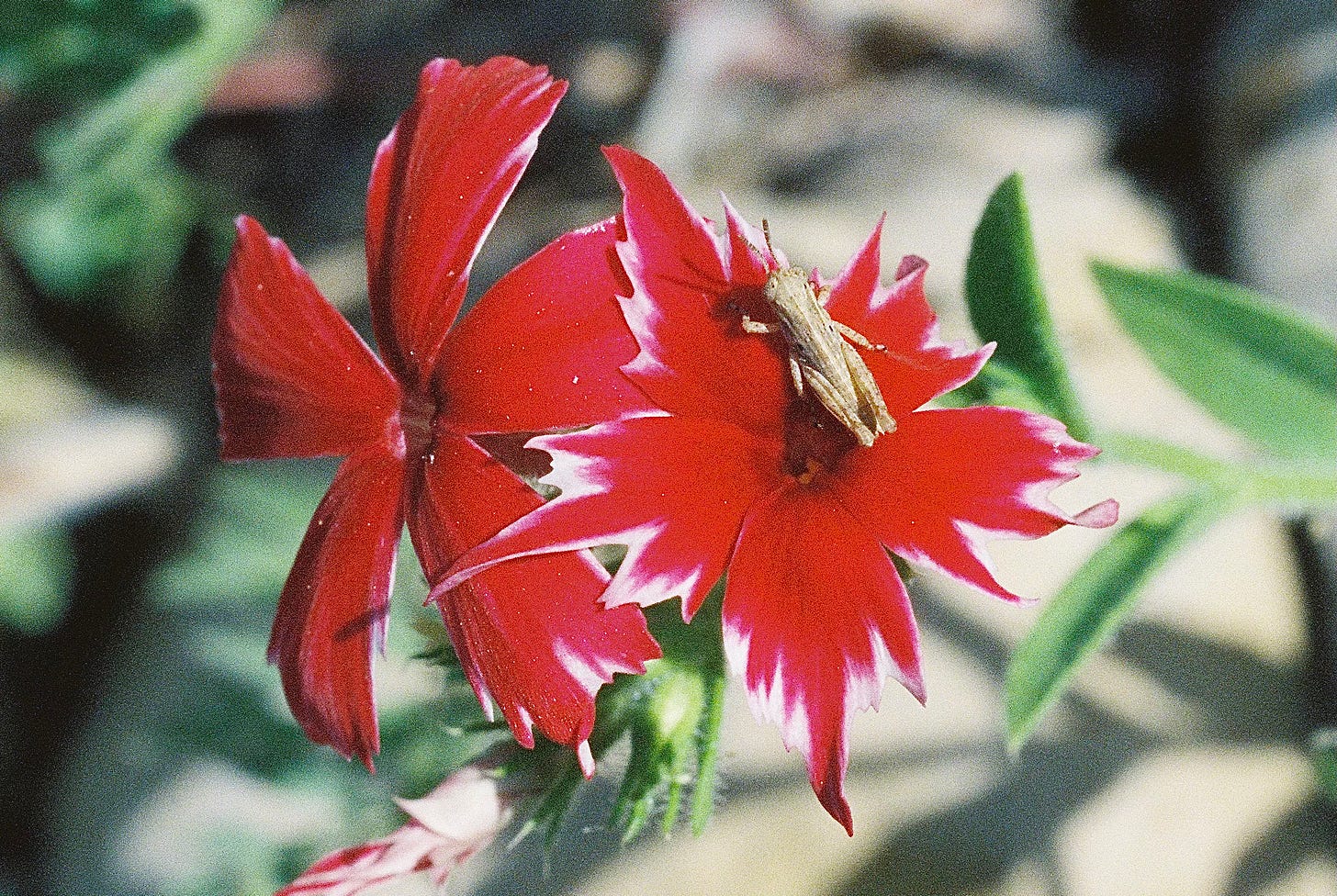

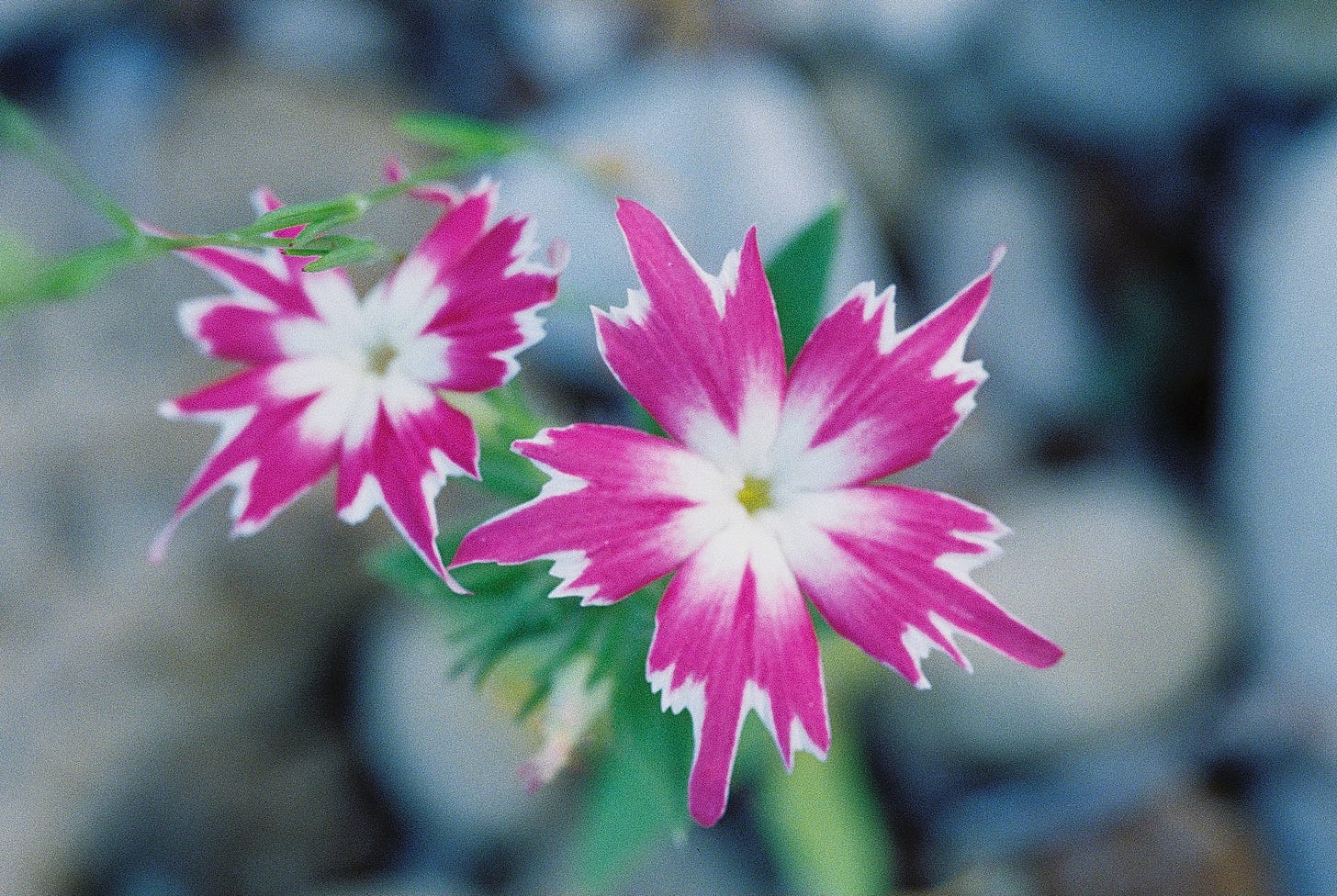

The names the copywriters give the moons draw from diverse traditional associations of different seasonal moons with important environmental changes—Indigenous and farm country ways of using the moon itself as the almanac, a mnemonic repository of cultural knowledge about how we live off our environment. In the Great Lakes and the northern Plains, April’s full moon was variously remembered as the time when the ice starts to break, the ducks come back, frogs start croaking, and the fish start biting. The Pink Moon refers not to the color of the object in the sky, but the wild phlox blooming on the ground. As it did here this week, right on cue, more abundantly than last year:

Ours is not the phlox the almanac writers meant, and it only recently started to appear on the rocky urban riverbank behind our home, which has been rewilding a little bit more every year we have been here, after having been used as a gravel dredging site for much of the 20th century. The bluebonnets always come up in that spot, in varying degrees of abundance. Last year there were just a couple of the phlox mixed in with the lupines, but this year there are dozens, in a Pantone album of showy pinks and flamboyant star-shaped petals.

A little research indicates it’s likely a mix of Phlox cuspidata and Phlox drummondii, which are said to have a knack for cross-breeding and producing new variants. New flowers, perhaps, for the new climate that has arrived in this zone, with swampy springs that precede brutally hot summers.

The full moon also had the mama turtles on the move, out looking for spots to lay their eggs. Saturday the pup and I saw one taking a rest in the shade near that patch of phlox, and Monday I spotted another one crossing the road behind Zilker Park under the Mopac freeway bridge, the wet mud still visible on the back of her shell. I had an instinct to help her make it safely to the other side of the double yellow lines, but she seemed like she had it handled.

The turtles often travel far from the water, looking for safe spots to lay their clutches. They sometimes show up in our yard, up a steep bluff a quarter-mile from the river. Which seems like a good adaptation, as this is also the season when you will often find the rubbery white shreds of turtle eggs that have been dug up by raccoons.

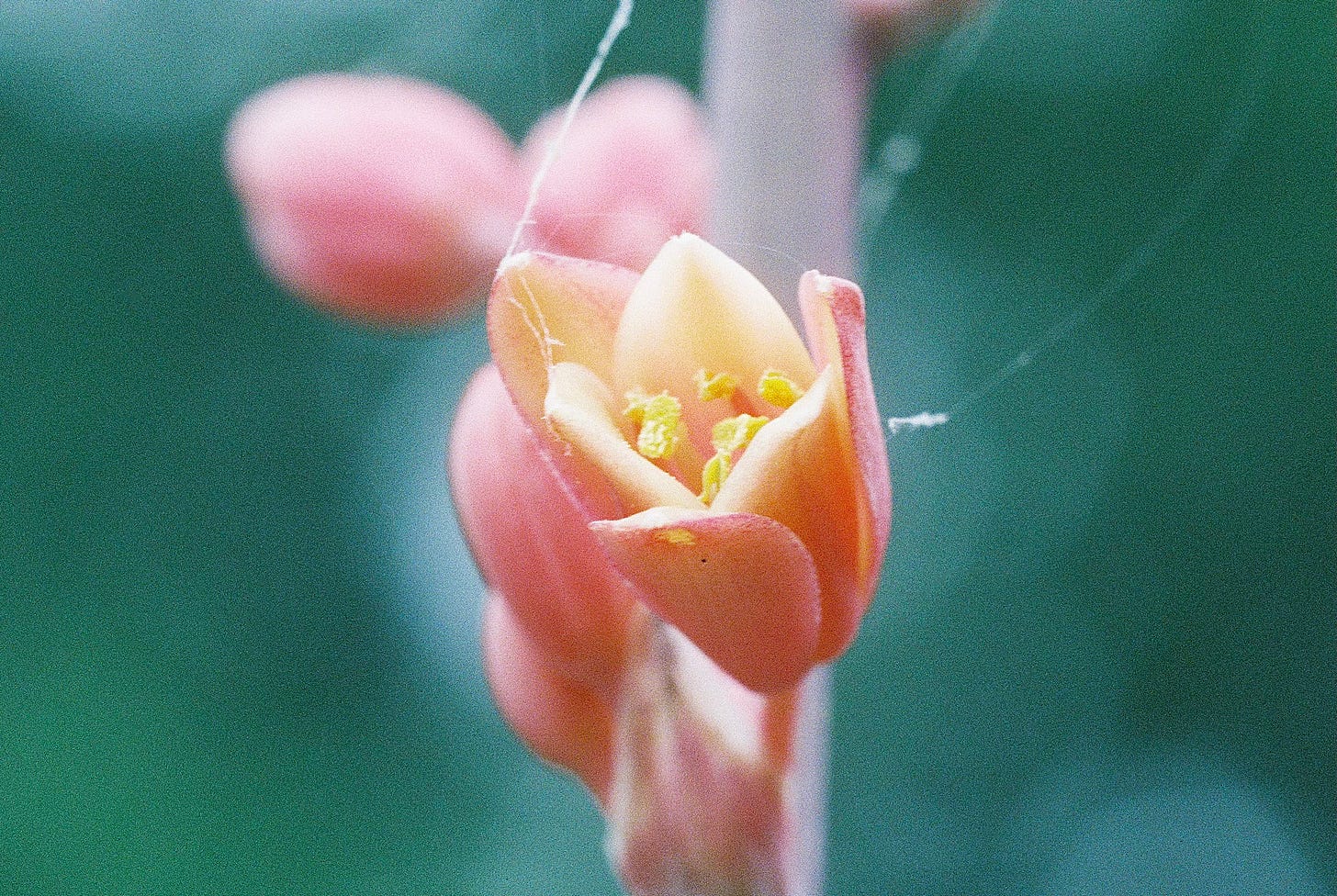

Monday while I was showing my visiting colleague Pam Penick around the place, I spotted a newly hatched red-eared slider trying to find its way across our front yard in the direction of the water. I decided to help that one, in consideration of the evolutionary handicap I had encumbered it with by having our dogs out, and worried that our four-month-old terrier would find it if I didn't.

The turtle conservation groups are quick to note that you should generally assume a turtle knows where it is going, even if it is crossing a road away from a body of water and towards some rocky embankment. And even the hatchlings have highly evolved homing, despite having no learned knowledge of the landscape into which they are born. When I find one, if there are dogs out, I usually set it just outside our back gate on the path to the river.

When I turned the baby turtle over, I was struck by the beauty of the pigmented pattern on its plastron. Like a face with bat ears, or two hands making the heart sign. The scientific literature explains that the shape of the plastron, concave or convex, is a good indicator of the biological sex of the turtle, and the first part of the carapace to have evolved, in a slow evolution and expansion of the sternum into a kind of under-armor. But while the patterns, which are as individualized as human fingerprints, provide biologists with an easy means to identify subjects for study and censuses, their purpose thus far has only been guessed at—camouflage, mating attractor, distinctive mark of identification within the species.

Research also revealed that this turtle was hatching ahead of schedule. Evidence of another adaptation to a warming climate, perhaps, or to the challenges of this family’s urbanized habitat, or maybe just an anomaly.

When I got the photo back from the lab and the intense beauty of these markings really registered with me, I thought about all the tiny turtles that will be hatching in the coming months, and trying to find their way across the city to safety without being intercepted. Maybe that’s just a sympathetic projection of the feelings in the human air, of all the folks in our community who are now afraid to leave their homes at night for fear of being detained and separated from their families, and have to navigate a landscape of danger every day when they go to work. Or maybe I have the promise of Easter and its pagan precedents on my brain.

The day after my mom and I drove past the scene of three men hanging on three crosses outside the Church of Cristo el Rey in East Austin as we drove to family dinner, a rehearsal of the Passion Play that will be re-enacted today, I spotted a new cardinal nest in the crook of a young tree right by our front path. Those nests have become easy to identify after 15 years in this house, for the way they ingeniously use industrial packaging and other anthropogenic materials available in this neighborhood of factories, warehouses and woodlands to keep their nests drier and warmer (I’ve written about them here more extensively before, and there’s a subchapter about them in my book A Natural History of Empty Lots). This one mixed plastic sheeting with dead leaves on the outside, in a spot around six feet above the ground. Taller than me by a few inches, so I decided to reach up and take picture to see if anything was in the nest:

When you’ve lived through five decades of seasons, you accumulate a better feel for their signs and contours. The recent seasons, though, have felt different than any that came before, even as they have some of their own weird emergent patterns, like the way the cardinals nests reveal the cyborg we have made of our world. This week leading up to Easter I got that sense of another brutally hot summer to come. I also got a stronger sense than ever of the human pressure building, as people’s sense of justice is daily tested and taunted. Someone should make an almanac that predicts when that kind of pressure boils over into mass action.

I wonder if the animals that share our habitat with us know how to see the developing human weather better than we do, like the elephants who were caught on zoo cam last week circling up to get ready for the earthquake. I’m pretty sure they’re already showing us glimpses into what’s on the other side.

The Roundup

Thursday, May 9, I’ll be at First Light Books in Austin, discussing A Natural History of Empty Lots with Megan Kimble for the Urban Austin Reads series. RSVP here if you’d like to attend—should be a fun and interesting conversation.

Thanks to Matthew Miller at Cool Green Science, the blog of The Nature Conservancy, for including Empty Lots in this roundup of environmental reading for Earth Day 2025. And for a different perspective on the rambles I mostly chronicle here, check out Pam Penick’s report from our walk on Monday.

Over at The New Yorker, D. T. Max visits the lab where Colossal has bred puppies with the DNA of dire wolves. And thanks to Chiara Sunshine Beaumont for tipping me off to this video about the Karankawa’s collaboration with Colossal around the cloning of a ghost wolf.

The Guardian reported an important new study out of Australia on the “extensive and multifarious” adverse environmental impacts of domestic dogs—much of which is attributable to the behavior of the dogs’ owners, especially letting dogs off leash in areas where wildlife are active.

Ballardian and Borgesian at the same time, this week’s NYT had a fascinating report on the capybaras that have flourished in a gated community in metropolitan Buenos Aires, and the ways their affluent human neighbors are responding.

Also at the Times, I was moved by this field dispatch by Daryln Brewer Hoffstot about gardening in time of climate crisis, and blown away by the accompanying photos by Kristian Thacker, which really captured the feeling of winter’s end and spring’s early beginnings in these weird times. You can see more of his work here.

I was lucky to get an advance reading copy of Joanna Pocock’s new book Greyhound, forthcoming this fall. It’s the story of a woman in her fifties’ journey across the U.S. by bus in the aftermath of Covid, retracing a similar trip she took almost 20 years earlier, and revisiting novels of the great American road trip along the way—all while aiming a keen eye at the landscape, human and natural. Erudite, empathic and intensely engaging, the book reads a bit like a visit from a time traveler, and stuck with me especially in the way it bears witness to how the damage we feel in our own lives and communities is rooted in our damaged relationship with the land on which we live. Greyhound also includes some amazing photos by the author—in black and white, but here’s one in color she kindly shared with me:

For a great short fiction about coming to terms with a dictator, track down a copy of “Somoza’s Dream” by Daniel Orozco, about the assassination of the deposed Nicaraguan ruler while he was in luxurious exile in Paraguay, told from the POV of Tachito himself. I reread it last night after finding my copy of McSweeney’s No. 18 (from way back in 2005) while unpacking boxes of books from storage to shelve in our new guest house library. It’s as good as I remembered, and a masterful example of a story that finds its way into the political through a craft-focused fidelity to literary truth. I couldn’t find an online version, but it’s included in Orozco’s collection Orientation, which is still in print and available at many libraries.

Also on my topical re-read shelf after escaping from the storage locker: The Great Leveler by Walter Scheidel, which looks at the the ways in which economic inequality has been successfully (if always temporarily) reduced in a meaningful way over the long course of human history since the stone age—through the “Four Horsemen” of leveling—mass-mobilization warfare, transformative revolutions, state collapse, and catastrophic plagues. Door number two?

Have a safe week.

As always, the one blog I read to the very end .... with no skimming! Love every moment I'm in your great, good company. Thanks1

I was thinking that I had stayed in bed too long this a.m. while starting on my first espresso and opened this essay and started reading. The first paragraph is like being run over by a truck. In a good way, Christopher. Damn. Damn! I don't want to flick you with seemingly faint praise by saying that your photos also put a tear in my eyes, but they do.