Chupacabras and bird brains

Last Sunday morning as I was cleaning house, I heard our dog barking, the kind of bark that raises the alarm. It sounded like she was up toward the street, where the passers-by are often the sort of people that make dogs edgy, but when I stepped out I realized she was on the overlook, hackles raised at activity in the woods behind our house. Coyotes, a pair, right at the gate.

Their quicksilver coats flashed sudden movement as they took notice of my appearance. One ran east, with a strange gait, a kind of stiff hop, forelegs then hind legs. I’ve seen coyotes pogo before, but this was more like a coyote imitating a frog or a rabbit. Maybe the trickster thought I would be tricked.

The other one took its time, walking at a relaxed pace along the trail at the base of the bluff. This one was mangy, with a bleached out clumpy coat that made it look like some Claymation Chupacabra. We watched it for a long couple of minutes as it headed west in the direction of the camps that cluster along the dam, and the gleaming new high-rises of downtown.

This weekend when I checked the field cam the sighting had motivated me to put back out, there he was on Wednesday morning, stalking up toward the backside of the door factory while the rest of us were at work. When I looked at the video the second time, I noticed his companion in the background, moving in such perfect yet distant synchronization that I wonder if it was some optical baffling. Like maybe they are figuring out how to trick our robot eyes.

Later that Sunday, as the last of the sleet pack melted off and we waited for the boil water notice to be lifted, we saw that one of the cardinals that lives on or near our lot was rustling around in the vines that hang from our roof. Every spring we get at least one nesting pair, and often more—in 2019 we had four. They like the cover, and perhaps the altitude, of the native cross vine that grows from the edge of our green roof and dangles over the windows of our living room and bedroom. If you grabbed those vines, as I do when I’m weeding the roof or washing the windows, you wouldn’t think them a very firm foundation to build the shelter in which you will raise your young. But songbirds don’t take up as much space as we do, and most of those nests last several seasons past their intended use.

The one that fell during the winds of the week before last had been there since the pandemic began in the spring of 2020. I had written about it here, noting what a wonder it was for our young daughter to be able to open her eyes in her crib, look up and see the little baby birds poking their heads out when the food showed up.

She’s old enough now that, when one of those nests finally gets blown from its remarkably engineered moorings long after its inhabitants have left, we can inspect in closer detail how those nests are made, and the way the birds use what the scientists who write research papers about such things call “Anthropogenic materials.” While our daughter is beginning to get her diction around some four and five-syllable words, it’s easier and more honest to call the material of these cardinal nests what it really is: trash.

We have a lot of trash in our neighborhood. We live at the end of a little side street at what once was the edge of town, surrounded by factories and warehouses on one side and by the urban woods and floodplain of the Colorado River on the other. The river corridor is always full of trash, as every flood brings the things that got left outside in the rain. When I walked along one of the side channels upriver from here on Thursday morning with a friend, we noted how the little side channel below the abandoned muffler shop glistened with fragments of polished glass from much older trash, mixed in with the newer layers of mussel shells.

Up above on the ancient alluvial plain, every unfenced empty lot gets used as a dumpsite by people who don’t want to spend the money or take the time to go to the landfill. On the weekends when I am working in the yard I often see such characters, slow-rolling in overloaded pickups scanning the landscape for just the right spot, and often trying to make their drop right outside the gate where the road ends.

The factories and warehouses, nodes on the global supply chain, generate a lot of trash. Next door to us they make commercial doors from steel and glass. Across the street the county government provides home infrastructure for low-income households. Next door to them they make “the Stradivarius of Windchimes,” next to them is a custom lighting design studio operating out of an old auto body shop, and next to them is a hipster chop shop where they convert Sprinter vans and vintage VW buses into the post-pandemic travel wagons of 21st century nomads. Most of the trash these places generate gets properly disposed of in commercial dumpsters and recycling bins. What the animals take are the fragments so small that we don’t even really notice them, or can’t be bothered to take the time and energy to salvage.

I’ve seen enough of these nests over the decade we’ve lived here to compile an inventory of the fragments the cardinals appropriate for their own use. They especially love the white Polyethylene open-cell foam that is used as an internal wrap for hard objects shipped inside corrugated cardboard boxes. It’s easy to imagine how much of that there is around the loading docks of the factories and warehouses, the slivers that tear loose in the wrapping and unwrapping. You also find a lot of clear plastic wrap, and sometimes you find bits of white printer paper, usually inscripted with fragments of some shipping order or invoice.

The one we found in pieces on the patio last weekend was not as deconstructed as we thought. And as we disassembled it, we were amazed at how complex it was, with multiple layers of varying materials woven into a snug little bowl you could hold in the palm of your hand. The core structure was made from seemingly endless spools of long thin stems of dried-out tall grass. Inside that, a layer of clear plastic that seemed to have been crumpled up by a human hand and then flattened by a boot or a tire, printed with bits of blue ink, one piece with the letters T-EXHAUST. Another layer of wider blades of grass, maybe inland sea oats. A layer of white paper that looked to have once been wet, and unfolded to reveal an H-E-B pharmacy receipt from 2018, the items sold too obscured to read.

Further in, two different bits of the cellophane that originally packaged some snack foods, maybe packs of crackers or cookies, their ingredients and warnings still legible if incomplete. The part of a beige Subway to-go bag that had the logo on it. A seamed piece of a grayer plastic bag, printed in French with part of the address of the California corporate banana farm from which it came, zip code 91361. A few bits of that open-cell white foam insulation. The clear plastic wrapper of a Black and Mild cigar. The long thin tear-off strip that was used to open a different smoke, one packaged in gray and printed along the entirety of its length with a lawyerly pome:

aging, or color should be interpreted to mean safer. Nothing about this cigarette, packaging, or color should be interprete

I don’t know to what extent the cardinals rework the materials they find beyond the remarkable weaving they do, but I know other birds convert the found materials through the application of their labor into something very different. Some take paper and chew it into pulpy insulation. Others do similar things with the threads of fabrics:

In Mexico City, sparrows and finches of the same species we see around here frequently tear up cigarette butts to use the cotton fibers for their urban nests. The jury is still out on what effects the toxins in those fibers—ethylphenol, titanium dioxide, propylene glycol, insecticides, and even cyanide—have on the fledglings.

The use of human materials for avian nesting is not new. Old bird books are full of remarks about cardinals using bits of cloth and string. But their adaptation to the thermal insulation and waterproofing made possible by plastics seems a different kind of leap. And if the ornithologists are right that the typical cardinal only lives for three years, it seems clear that the knowledge about how to insulate the nest with industrial materials is somehow being passed on between generations of birds. One wonders what they’ll figure out next.

Lupercalia reading list

“The Pygmies of Gabon use the shell of a large land snail for cutting the hearts out of small animals they sacrifice, and for circumcising babies.” So wrote Carleton Coon in The Hunting Peoples, a used Penguin paperback copy of which I picked up in December and started reading this week. The book is of the vintage that, when the author talks about the importance of hair among certain pre-agricultural societies, he can’t help but make a crack about his own hippie kid. And reading the titles of the Harvard professor’s other works in the bio, there’s reason for deeper suspicion about how trustworthy an authority he was. But I was intrigued by his discussion of pit houses in his section on shelters and hearths, especially his notes that Upper Paleolithic hunters of southern Russia used mammoth bones to hold up the roofs of theirs, and certain Inuit used the ribs and jaws of whales.

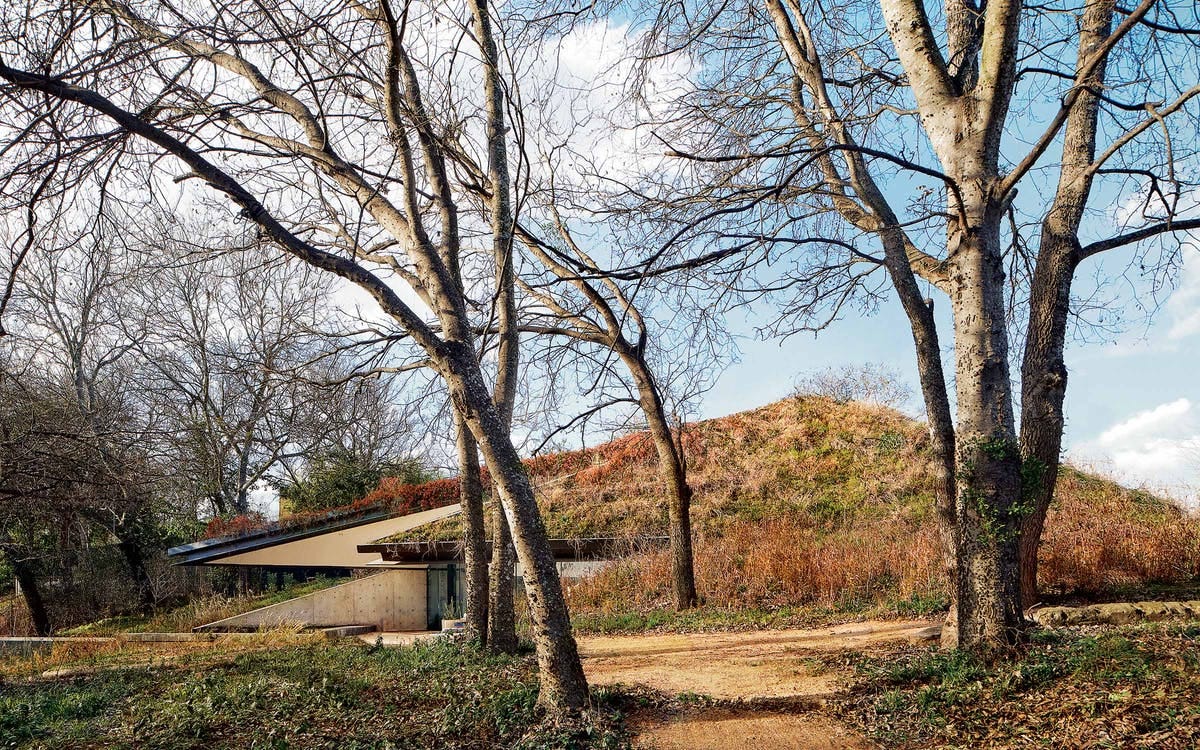

Our own bunkered up version of the pit house uses concrete and steel, and was the subject of a generous feature this week by the poet and independent journalist Julie Poole for the March issue of Texas Monthly. I know Julie from her tenure as a bookseller at Austin’s Malvern Books, and I was delighted to read her closely observed report on coming over to visit. She even gets in a good word for these Field Notes. And the photography by Casey Dunn really brings out the beauty and color of the house in midwinter. Full story here.

And over at Transfer Orbit, Andrew Liptak has the full transcript of a conversation he and I had a few weeks back about climate fiction, including a reconsideration of some canonical American novels as such. Andrew is an insightful interviewer and an incredibly hard-working independent writer, and his newsletter is perhaps the best out there on the subjects of fantastic fiction and the business of science fiction. This interview was originally conducted for Andrew’s piece about climate fiction for Grist, but my comments didn’t survive the editorial condensation, so it was nice to see the whole conversation end up as its own piece. (There are a few spots where my Midwestex mumbling confounded the transcription bot, but the ideas come through just fine.)

Thursday morning the writer Wes Ferguson and I went for a morning walk down on the landfill island with the insane heron rookery I wrote about here before the holidays. The elephant ear had all been frozen back to its knobby roots by the recent freeze, and as we walked the momentarily blighted plain of the west end of the island Wes remarked how it made him think of descriptions of the unexpected wilderness of the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Wes is a writer who broke out writing about wilder Texas rivers than the Colorado, and spent the last few years writing amazing pieces about hunting and the outdoors for Texas Monthly. You can find more of Wes’ work here. If you want one nice little Field Notes-adjacent piece, Wes’ November 2020 report on the expanded range of the Caracara is pretty great.

As nice as it is getting coverage of one’s interests and work in a magazine like Texas Monthly, I always find myself somewhat suspicious of the way magazine stories, like most other American narratives, tend to focus on one individual. I always think the real story is about family and community and immediate ecology, and the individual as a part of it. Reading Julie’s piece, which touched on all those angles, got me remembering how I found love and new family exploring these weird urban wilds. That’s the sort of story you mostly keep to yourselves, but writing this on the eve of the romance holiday got me remembering the piece I wrote on our wedding day in 2013 on the connection between this place and our relationship. “Requiem for a Muscle Car” is over on my old and mostly inactive Tumblr, but I think it holds up pretty well.

And for those who made it to the end, here’s the full video of Wednesday’s coffee break coyotes. It’s almost stereoscopic, when you look at it right:

Happy Valentine’s Day, and have a great week.

Wes Ferguson with Chris Brown! I want to be on that walk. Love Wes' books and writings. I see he's moving on from TM. And enjoyed Julie's piece on your space. Keep on keepin' on. Have a good week.