On the Beach

No. 136

“Yesterday kinda whupped me,” said the stranger.

He was in a wheelchair, working his way very slowly across the bridge at eight in the morning. Wednesday, Odin’s day. The summer solstice, in the hottest June I can remember.

I had an idea what he meant, having had the bad judgment to go for a run at 1:30 p.m. the day before. I also didn’t have a clue what it was like to navigate the urban landscape in intolerably unsafe heat the way he had to. He only had one shoe, and on the naked foot he was using to help propel his chair across the pavement, he had no toes. Diabetes, if you had to guess. He was a middle-aged white guy, maybe my age or a little older, with long hair, intensely lucid eyes, and a faded black T-shirt printed with a brightly colored rainbow of Jarritos.

I asked him if he needed help, and if he had a place to stay. He insisted he was fine, and said he had secured a place at the YMCA for the whole month, and was headed there at that moment. It was early enough that it was still safe to move around. The unsolicited SMS warnings from the municipality would start coming a few hours later.

I ran on, to my air-conditioned home. As I ate breakfast, I read a story buried in the morning paper about the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development in Kathmandu’s new report that the Himalayan icepack is melting, faster than any of the models anticipated, 65% faster in the past decade than in the decade before. One of those apocalyptically urgent headlines that can’t compete with the more immediate human drama of imagining things like what it must be like to be trapped in a bespoke submersible you (or your dad) paid $250,000 to ride in.

On the PBS News Hour, a white-haired saltwater scientist from the Scripps Institute explained what four-thousand pounds of pressure per square inch is like by holding an imaginary egg in his hand and crushing it.

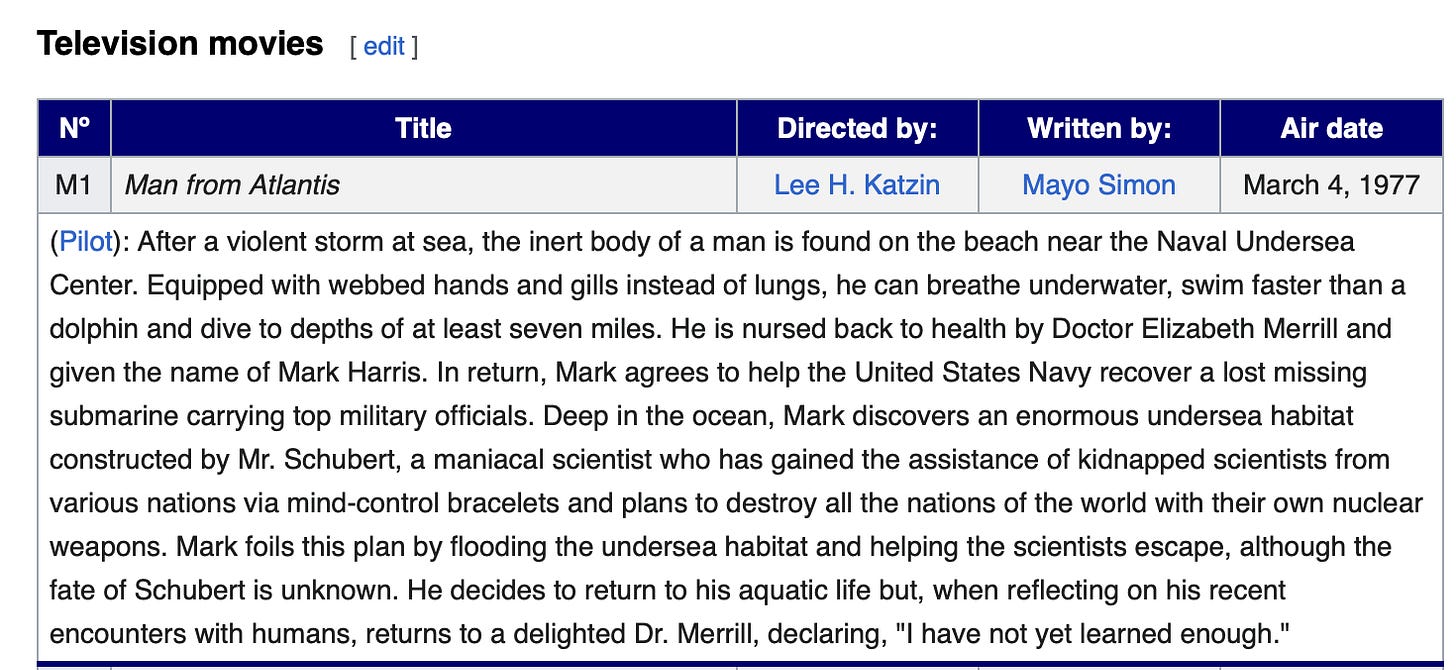

When I was a kid in the 70s, there was a wave of stories of human beings in the near future learning to live underwater, perhaps reflecting the growing recognition at the time that we were starting to render the surface uninhabitable. They were juvenile and utopian narratives—Sealab 2020, Man from Atlantis, all sorts of mass market paperbacks envisioning domed cities of the deep or future humans who had returned to the womblike aquatic pastoral, often learning to breathe through gills. These fictions mirrored real-world explorations in the same vein, like the women aquanauts who wowed the world with their sojourn in Tektite II and the ubiquitous, anticipatorily elegiac Jacques Cousteau specials that inspired everyone from John Denver to Wes Anderson.

Whether fantasy or documentary, these narratives all coupled science fiction’s romance of technological instrumentalism with an earnest, ecology flag idealization of the sea as the last clean place, the only part of the planet that had escaped our ravaging.

The climate in Texas this week was something different than what I have experienced before. The crazy triple-digit heat index numbers, pushing 120°F, tell part of the story, but they don’t really convey how it feels. Heat and sun that often reach these levels here in the worst weeks of July and August, but mixed with tropical grade humidity. Almost maritime, but with urban air pollution instead of sea breeze, an air that you can tell is no longer really optimal to breathe. So hot that it is really not safe to do anything outside during most of the day, unless it involves getting in the water. The weather of a summer solstice at the end of the world.

What a strange thing to live long enough to arrive in the future the science fictions of my childhood imagined, and to have its wonders and horrors slowly manifest as our everyday norms. There are a lot of similarities, especially to the cyberpunk dystopias of the 80s. Randian technobarons, one of whom lives and works near our home, are planning to colonize other worlds. The first vat-grown chicken tissue was just approved this week for human consumption. And some of us now spend most of our time in sealed and conditioned spaces that replicate the environment we evolved for in the more hostile atmosphere we are forced to live in. But it is not the world we had to retreat to, at least not yet. It’s the one we made too hot to sustain our own upward trajectory as a species, burning up the dividends of Prometheus to accumulate offerings for Demeter, and ourselves.

The undersea explorers are there, but what they seek in the alien worlds at the bottom of the sea is not the wonders of the last virginal space on the planet, but to see with their own eyes that most spectacular exemplar of the trash we leave behind, the wreck that best expresses our hubris. A double-header that’s hard to beat for a story that shows how the techno-libertarian idea of progress is not the path to a healthier future.

The night of the solstice finally broke the unrelenting oppressiveness of the air, with a thunderstorm that continued on and off into Thursday. But the relief was illusory. The heat didn’t really abate in a meaningful way, and the air just got steamier. When we got in the pool, my wife wondered out loud what weird new germs nature must be incubating in the waters to check our overtaking of the planet, and whether we should get a chlorine pod to aid our natural filters.

I wondered if that guy got where he was going, before the rain.

The Channel 8 News

In Des Moines, Chris Gloninger, the meteorologist for the local CBS affiliate, one of the channels I grew up watching, announced this week that he was resigning and taking an off-the-air research position at Woods Hole after receiving harassment that culminated in a death threat for his regular discussion of human-induced climate change as part of his weather reports.

Wednesday’s paper also brought the fascinating news of a study that identified a significant correlation between the coloration of Monarch butterfly wings and their ability to complete the epic annual migration from the middle of the North American continent to the sites where they overwinter in Central Mexico. (Those sites, and the length of Monarch migrations, were only discovered in 1975.) It’s not the first research to link the color of flying animal wings with their flying skills (and aquatic creatures’ fins with their swimming ability) —darker topwings more readily absorb solar energy, heating up the boundary layer of air immediately above it, thereby creating a pocket of warm air the wing can pass through more readily and reducing drag. Analyzing hundreds of Monarch photos while listening to true crime podcasts, Georgia student Tina Vu (and the professor, Andy Davis, who had enlisted her help to test his theory) found that the white spots at the outer edges of Monarch’s wings were bigger in those that made it to Mexico, suggesting an aerodynamic connection.

We’ll be watching for them this fall, when they often stop to enjoy the butterfly milkweed growing at the edge of our green roof.

Ein Riese ist von uns gegangen. I was sorry to read of the passing of legendary German free jazz saxophonist Peter Brötzmann, who broke through the soundscape of the Cold War with incredibly heavy improvised music, channeling the darkest sounds of the Zeitgeist in records like Machine Gun (1968) and Alarm (1981). Brötzmann came in peace, though, and was deeply tuned into nature. You could experience it best in live performance, like the show I saw in 2018 with Brötzmann’s skronking horn balanced by drummer Hamid Drake and bass player William Parker.

Consider Schwarzwaldfahrt, the product of Brötzmann’s 1977 trip to the Black Forest with percussionist Han Bennink, where they made xylophones out of giant logs, captured the sounds of overflying jets along with nearby wildlife, and played in conversation with the surrounding songbirds:

Ruhe in Frieden.

And RIP Teresa Taylor, the Butthole Surfers drummer who etched herself as a permanent fixture in the Gen X pantheon with her appearance in Rick Linklater’s Slacker, a kind of improvised movie about young people enjoying the wonders of a town in which the real estate economy has crashed and it’s okay to do nothing for a couple of years. I first saw her play with the band on the campus of Tulane University in 1983 or 1984, where they were an unlikely feature for the weekly Friday happy hour band on the quad outside the student union. The incredible, mind-melting performance transgressed multiple boundaries at the same time, into territory way beyond punk, and I appreciate the impact she had.

In other butterfly news, the tangerine dreams (aka Gulf fritillaries) are back on the edgeland passiflora that grows wild on the chainlink here where the double dead end meets the empty lots. They have some white spots at the edge, too, and that orange seems to also have some aerodynamic benefits. I’m just happy to see them, and to be reminded how much we don’t know about the natural wonders that surround us. A butterfly whose exclusive host is a plant that grows like a weed in the run-down edges of town. Maybe we’ll learn to appreciate their secret powers and gifts enough to better make room for them while we still can.

I’m not sure of the schedule for this newsletter the next couple of weeks, as I plan to be in the field for some of that time, but will be back after Independence Day at the latest.

Stay cool, and thanks for reading.

And add the buckling of the Katy freeway and things start to creep towards failed state. RIP, Teresa....

Queen butterflies on your roof…