Hothouse birds and Nostradamus nerds

Friday afternoon I spotted a fisherman pulling a Bird out of the river, on a long line hanging down from the old bridge.

I couldn’t see the human at the other end, or whether they had a pole, just the scooter there slowly twisting. The fact that I could tell which brand of bro-mobile it was from a hundred yards made me wonder if I could as easily identify any actual bird at that distance. It seemed like whoever held the line was trying to pull the Bird up, but even that was unclear, the way it would ascend and then drop back down or just dangle. Chances are it was one of those wranglers paid to extract the devices from the strange places they get left and return them to base for a more orderly re-deployment. But it also could have been someone trying to dump it in the river, or repurpose it as conceptual street art there amid the graffiti-covered pylons that hold up the tollway.

I had an audience of two watching me as I watched the scooter. A grey-haired petro-nomad hanging out with her dogs in a lawn chair outside the screen door of her Holiday Rambler, which has been parked there under the bridge for a few weeks now, and a younger lady in a green cotton dress who looked like she had probably just walked up from one of the camps in the nearby woods. She sat on the concrete shelf as I worked my middle-aged body through my last sets at the calisthenic stations the mobility authority installed last fall. We all three turned our heads when the first real angler showed up, rumbling off the bike lane in an ATV augmented with orange fishing poles tied to the rear like whip antennas.

I had run there in the mid-day heat along the high berm the machines built between the onramps over the last few years, one of those curious bits of Anthropocene topography that quickly gets adapted to uses its engineers did not anticipate. Sometimes we see riders on horseback up there on the high crest, an atemporal vignette that reminds you on a hothouse summer day that it may be a vision of the future as well as of the not-so-distant past.

The animals use that berm, too, mostly the hidden trail that parallels the downtown-bound off-ramp. You can see their tracks in the dusty sections being colonized by harvester ants, or in the denser earth after a rain. In the shade under the junction of the two eastbound onramps I finally spotted the carcass I have been smelling the past week, a young deer that didn’t make it through its first summer. And on my way back down along the terraformed ridgeline I found the fur of some coyote whose gift for baffling the light may have caused its death in traffic.

Down in the woods at the far point of my run, I encountered a birding couple so raptly focused on whatever they had found there in the flooded creek that they did not notice me trot up behind them. I couldn’t see what they saw—maybe a night heron, I guessed. The channel of the creek was cut by the water from the nearby roads and factory parking lots, but the water came from the dams upriver, released on summer mornings to aid the rice farmers closer to the coast. It will be dry soon, as we haven’t had more than a few hours of rain since Memorial Day, and the releases will be suspended as extreme drought settles in.

When you endure apocalyptic Texas summers like this, especially if you pay attention to the local headlines that are even more troubling than the weather, a reasonable reaction is to consider healthier places to live. The Texans who can afford it tend to run for the Rockies in the summer, and at parties one hears lots of talk about ways one might procure a passport to some European country through an immigrant grandparent.

My wife and I were talking this week about perhaps finding a way to spend more of the summer in Iowa, where my parents live, but then we looked at the weather and it was basically as hot there as it was here. The truth is the only place there is to go is into the future we have made for ourselves. And when you get out in the middle of a triple-digit day and travel the paths of the people who get by without access to air-conditioning, you get a sense of what that will feel like. Its entropic languor even has a certain attraction. But then you get to wondering what animals will be left to share that future with us.

When we got back from Marfa on Juneteenth our visiting Magonista friend wanted to see the edgelands he had read about in this newsletter, so we walked down along the river and into the weird woods. It was already brutally hot by 10 a.m. that morning, and when we stepped out of the shade of the forest onto the rocky beach of the old gravel dredge, the glare off the river stones, shells and fossils was blinding. But as we adjusted to it and stumbled along, we began to notice that the zone was also littered with the shells of dead turtles. One, then three, then more than a dozen, spread out every few yards, mostly overturned and half-desiccated but still fresh enough that you knew whatever had caused their deaths was recent.

A single dead turtle is not unusual, but this was a strange mass death, its cause hard to deduce. Did they die from the heat? From some discharge or toxic bloom in the water? From some evil kids killing for pleasure? Maybe the vulture and the caracara watching over the scene from the high branches of a dead tree knew.

The most exotic bird I saw this week was a man with ankle wings. A lithe white dude who emerged from the trunk of a white Honda right after sun-up on Saturday morning, dressed up like some glam band Prince Namor, wearing nothing but black jogging shorts and a pair of Talaria made from yellow reflective safety vest material wrapped around his shoes. His head was shaved and his eyes painted with feathery black flourishes. He was there loading up after a late set at the Electric Church when my daughter and I returned from a syrup run, the last of the three cars that had been parked there before dawn when I first walked out to my office to get to work.

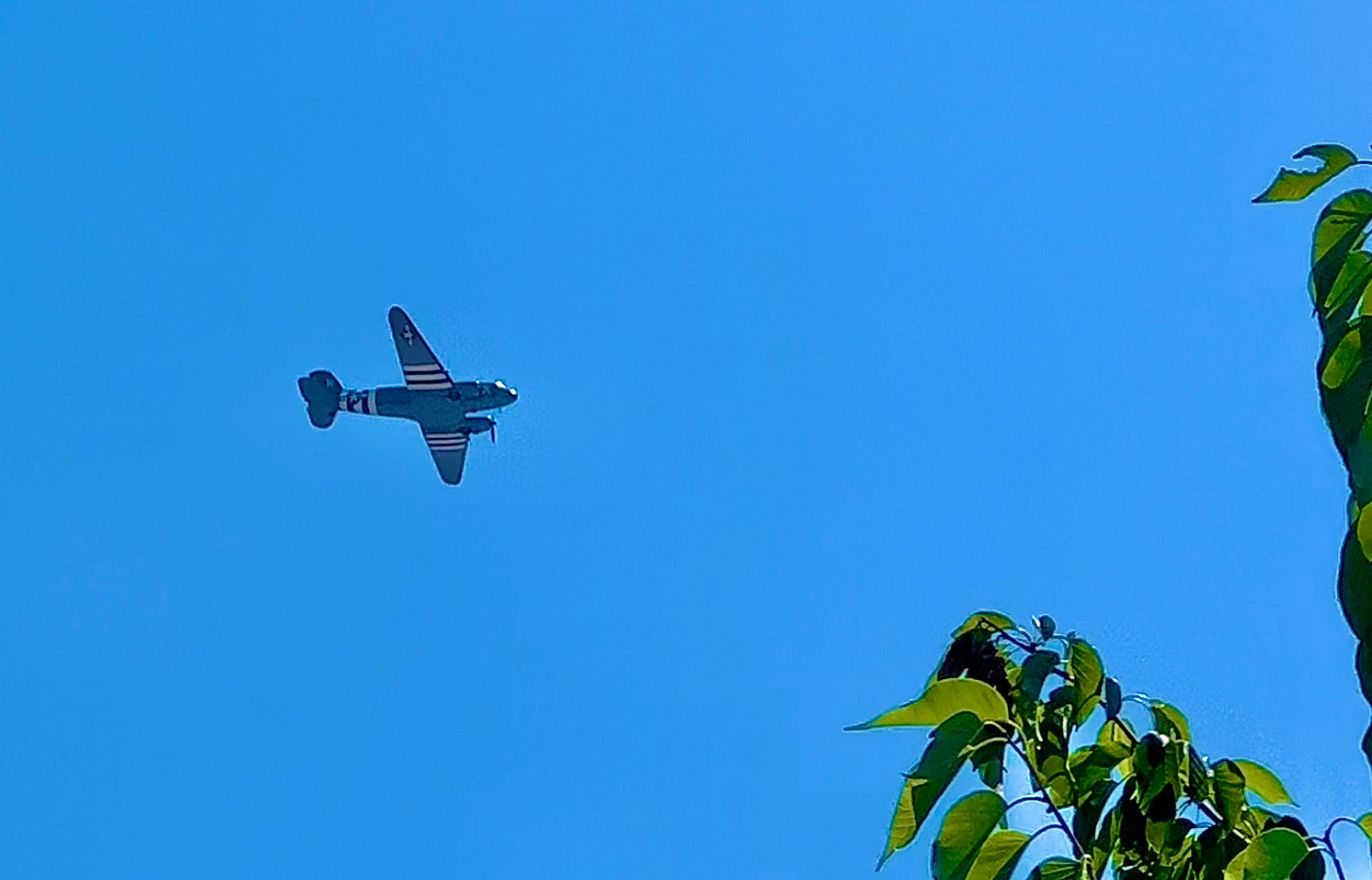

Maybe even more exotic was the B-17 I saw flying over our house the Saturday before Independence Day, a slow motion sky machine I only saw because I heard its anachronistic rumbling first. The appearance two days later of a C-47 transport—one that had actually delivered paratroopers to Normandy on D-Day, I later learned—confirmed that it was air show rather than hallucination. They no longer call themselves the Confederate Air Force, but the name sticks in your head.

A more common sighting over the past couple of weeks has been hawks being chased off by songbirds. The interceptors one sees pecking at the backs of the raptors are usually mockingbirds or grackles, and it’s always remarkable, like seeing a pack of chihuahuas chase off a timber wolf. The scientists call it mobbing, an antipredator adaptation. It made me think there must be young birds around, even though the one active nest we have found around our house—a cardinal nest in an ornamental tree on our patio—was abandoned when the eggs did not hatch, likely because of the heat. Six weeks later, the eggs are still there. Safe from predators, but apparently not from the changing climate.

The prematurely hot and sunny summer has the sunflowers in bloom earlier than usual, and in the evenings the lesser goldfinches come around to dine on the seeds. When we finally emerged from our Covid quarantine we hung out with our biologist neighbors in their backyard and watched a posse of them, and Dr. Atkinson suggested it’s the only thing they eat, which turns out to be right. They do not know we call them lesser, and if you ask me their adaptation to live off one of the most bounteous and weedy tall plants of our hemispheric hot zones gives them a superior edge.

On Wednesday’s run I came upon another sign of life: a turtle laying her eggs on the trail down by the river, in dirt full of old trash and concrete rubble. A sight normally associated with cooler spring temps. It got me wondering whether the creatures around us try again to breed new young when our damaged climate or other factors confound their usual patterns of reproduction.

On Saturday morning, as we walked back into the house after our encounter with hipster Hermes, we spotted a mama cardinal up in the Virginia creeper that hangs from our green roof over our windows. To our surprise, she was building a new nest, with the usual mix of native plants and industrial packaging materials.

When we first saw her, her beak bore a fragment of clear plastic wrap bigger than her. We watched as she worked it into the base of the nest, in a tiny spot well-shaded by the foliage that has managed to grow thick despite the dry season. A little later, as my daughter and I headed to swim school, the cardinal was there in the bois d’arc tree, with what looked to be the remains of a wax paper food wrapper. Another vignette from the natural history of the future, one in which we and the animals that endure our long dominion try to stay cool enough to procreate, making what shelter we can from the remains of the extractionist culture we will eventually leave behind. Whether we get there through foresight or collapse remains to be seen.

TBR

After our Juneteenth walk, the Chilangringo and I spent a day running around Austin, starting with Daniel Johnston and the Ransom Center’s excellent exhibit on Women and the Making of James Joyce’s Ulysses. Pepe cleaned up on avant poetry at the amazing Malvern Books, and then on vintage comics at Austin Books. It was my first trip to the comics shop in a long time, and the end of the world heat motivated me to buy two issues of Jack Kirby’s Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth.

The Omicron strains we also brought back from Marfa with us compelled us to postpone our Independence Day trip to visit big brother. We got through our first cases pretty easily, though my wife had one scary night, and we all gained a deeper appreciation for the virus’ capacity to wreak serious damage, and the risks that mutations will outpace the potency of vaccination. You can kind of feel it working its way through your upper respiratory system, looking for the weak spots. I found myself remembering some of the early reports speculating that its species crossover from bats had resulted from our destruction of bat habitat in the edgeland sprawl of Wuhan, and my instinct that there is some sort of ecological rebalancing at work in this pandemic.

On the Tuesday after the long weekend, I made a day trip to Houston, which afforded me a chance to have lunch with one of my oldest friends, the actor and director Philip Lehl, who runs 4th Wall Theater Company with his partner Kim Tobin. Phil was on his way to the rehearsal of Twelfth Night, this year’s installment of the remarkable summer Shakespeare workshop he has been teaching with two visiting students from Juilliard and a diverse cast recruited from Houston area high schools. We’re hoping to make it back down for one of the shows.

On the way back out of town I made time for a quick stop at Kaboom Books in the Heights, an amazing used bookstore that relocated from New Orleans to Houston after Katrina. My haul was small, reflecting insufficient time to browse, and short on nature books, but I did pick up a nice copy of George Stewart’s Earth Abides—a 1949 story about the survivor of a global apocalypse that follows a global plague facilitated by high-speed intercontinental transportation.

Two more reading links from this week’s mail: The July 7 issue of the London Review of Books has a great new diary from master psychogeographer Iain Sinclair, following Caroline Knowles in the explorations of her new book Serious Money: Walking Plutocratic London. And the July 21 issue of The New York Review of Books has an interesting piece by Aaron Motz, “Flaubert’s Planet,” considering whether novelists bear any responsibility for climate crisis.

Field Notes will be off again next week, while I am busy with a visiting documentary film crew. Have a safe week.

Beautifully written, as usual. Evocative and thought-provoking. Thank you.

Your newsletter is now my favorite thing about Sundays. Thanks so much for writing it :)