Frontage road tickseed and other ofrendas

No. 167

Monday morning as I walked out to the car I saw a hawk gliding high on a thermal, surfing the warm air pushing up along the bluff from the river. The hawk was so high that it was hard to tell what species it was—red-shouldered, red-tailed, or maybe even broad-winged. Probably the former, as that’s what lives in the riparian woods behind our house. High flying buteos are normally a spring thing, but this autumn brought the hottest October days on record, and by 9 a.m. the sun would cook the cool air that had settled on the river overnight, and send it up.

That vignette—an example of how the rise of warm air can enable flight without the expenditure of energy—got me thinking about my Uncle Hank from Cleveland, who died last year. The oldest of my mom’s siblings, and the only one who never lost his German accent, his full name was Hangwind, the German word for thermal updraft. A name chosen by his aviation nerd father, who, by the time Hank was born in 1927, had spent close to a decade with his buddies designing and racing sailplanes in the Rhön Mountains—World War I vets turned log cabin hobbyists who quickly figured out, flying without the engines Versailles prohibited them from having, aerodynamic forms that nature would lift higher, faster and further.

Hank was also on my mind because of the election news in the morning paper, which reminded me of the things my uncle had said about one of the candidates when he first ran in 2016. Telling us how baffled he was that his Ohio neighbors couldn’t see how much the guy was like Hitler. Hank had a certain credibility on the subject, as the only member of our family left who had actual memories of what that was like, having been sent off to a wartime boarding school devoted to the worship of the guy, then shipped to the Western Front at age 15, where he was captured by the British.

It wasn’t until this election season that I got to thinking maybe Hank's neighbors could absolutely see the same qualities in the candidate that he did, and that’s what they liked.

An hour earlier, I had found myself trading notes with my friend Bill as we stood on the grass at the edge of the tollway onramp, watching the Cybertrucks roll by. I’ve known Bill for a decade now, since we first met at the entry to an empty lot next door, but he has no phone, so we only get to catch up when serendipity happens, or in the letters we exchange when swapping books. Bill is an insightful critic, and a forgiving one, who hilariously wrote me in one letter that my novel Tropic of Kansas read like a cross between Walker Percy and Bomba, the Jungle Boy. When I started to ridicule the Damnation Alley cosplay of the Elon-mobile coming off the highway and headed downtown, Bill complimented how smart the design was, how efficient and beautiful, unprejudiced by its social cues the way I was.

I asked Bill how he was doing, and if he was feeling secure in his place, an otherwise abandoned little wood-frame building at the edge of an old gravel pit that has been slated for redevelopment as a new urbanist wonderland, one of several such projects emboldened by the rise of the Gigafactory just east of us. Bill said the asphalt recycling operation that has been working around him and tolerating his presence for the past fifteen years is getting ready to move out at the end of the month.

When I asked if he had any interest in seeing if there might be a way to get him some relocation support, maybe from the developers preparing to tear his place down, Bill kind of shrugged. He said he was in a good mood, having just started off his morning swimming in the river, and didn’t want to ruin it thinking about what was coming. We didn’t talk about the elections, though I know Bill is registered, having helped him get a new card back in 2018.

As an alternative to the news feed, I’ve been reading the Keneva Kunz translation of The Vinland Sagas, which relate the stories of the 10th century Norse settlements in North America. A lot of the content of those narratives is interlinear, but The Saga of the Greenlanders gives you a strong sense right on the page of how scared the battle-hardened Icelanders were of the Natives of North America, almost premonitorily so. Reading about Vikings loading their ships with as many Canadian grapes and grape vines they could before they hurried home, you also get some perspective on how long the European conquest of this continent took.

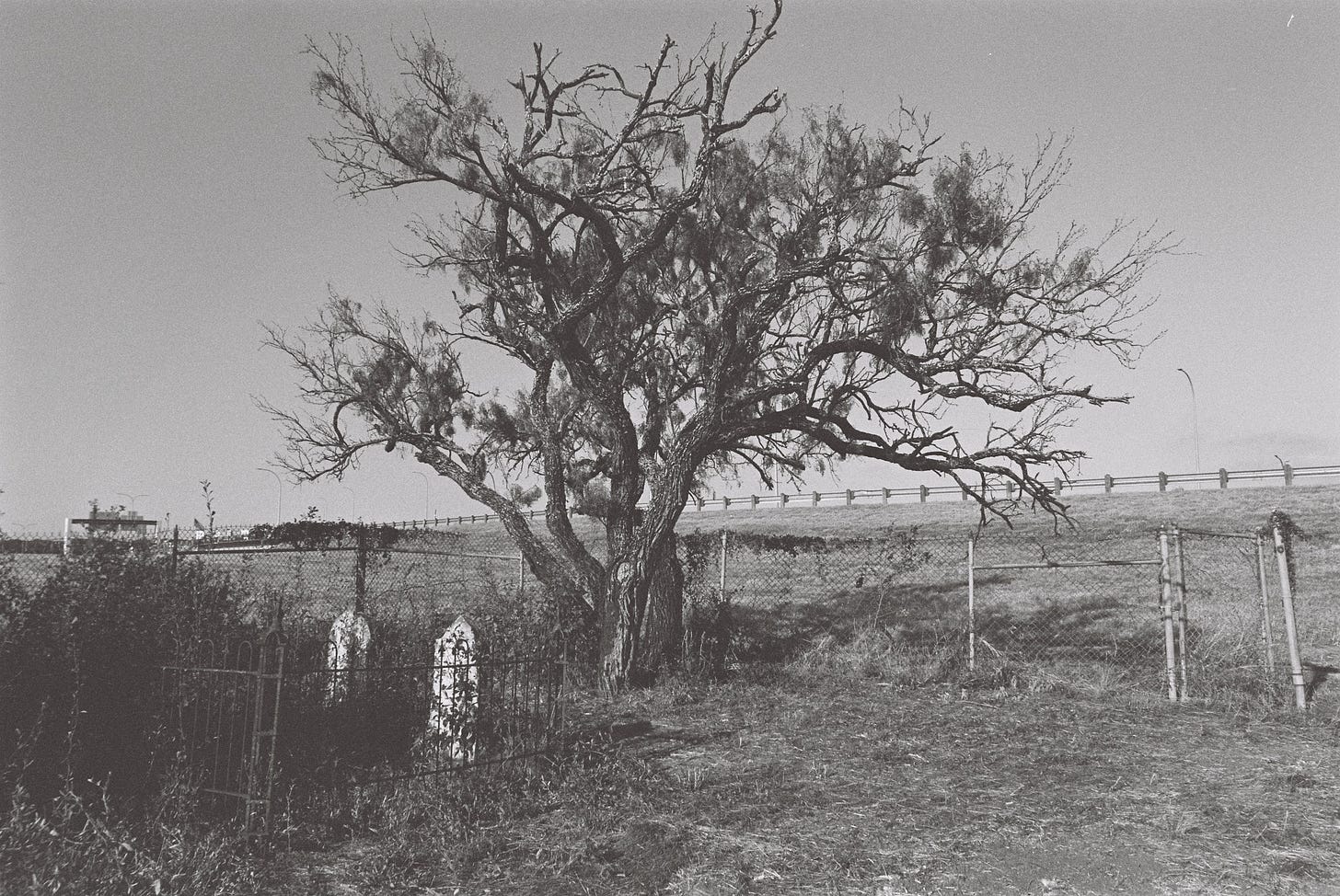

On Saturday morning, the Day of the Dead, I dropped my car off for service at the dealership and rode my bike the six miles home, much of it along frontage roads. Beneath the elevated intersection of Interstate 35 and Highway 71, I stopped to check out some Coreopsis in bloom along the old railroad tracks that run parallel to the sidewalk, right behind the weird 80s hotel where they hold the local science fiction convention. When I got in closer, I could see extensive clumps of sensitive brier growing in there, too, a plant that seems to thrive in unseasonably hot spells, and produces hot pink powderpuffs when it blooms.

Prairie flowers holding out in the thinnest of margins, there along what must be the routes of ancient trails first made by megafauna, give you a reminder of the resilience in the land, but they also remind you of nature’s exhaustion. Especially in a spot like that, where you can also witness the economic exhaustion trying so hard to convince you of its vitality. (Note the Star of Texas embossed on every highway overpass pylon, above the landscape that symbol has brutalized.)

I rode on, down the hill behind the sprawling IRS facility, through a creek bed, up a big hill through a quiet residential neighborhood, past a guy blasting opera at the bus stop while he dressed his wounds, through a canyon of half-constructed new apartment buildings closer to downtown, and then finally, two-thirds of my way home, picked up the trail into the woods along the river. I bumped into my friends Jesse and Michelle and their dogs moments after they had bumped into each other, and traded news about teen driving tests and Monday night free jazz at the neighborhood brasserie.

When I emerged from the woods behind the youth soccer field, where a game was underway, I heard a familiar whistle I hadn’t heard in many months—the one-note call of an osprey, back in town for the winter. And there it was overhead, with those jagged wings, tracing something close to the same path as me.

After I crossed the river and left the trail, I saw another raptor. A hawk this time, definitely red-shouldered, sitting on top of a telephone pole at the base of the tollway onramp, surrounded by grackles on every other line. I expected the grackles to haze the hawk, but they were busy foraging for pecans. I was surprised they could find any—across the road, a monolithic new parking garage just went up, and foundations have been laid for the apartments and office it will serve, on a lot where, until last winter, a grove of majestic pecans had been allowed to persist on a deserted traffic island, the triangle of land between two onramps. They saved the trees—I witnessed their strange excavation and bundling for transport—but where they went is mystery. Maybe the grackles know.

The idea of blindly following a real estate developer as your Pied Piper is quintessentially American, when you think about it. It’s kind of what George Washington was, and absolutely the origin story of the State of Texas. And when you read about Moses and Stephen F. Austin, and how the son came to think about his work—taking “sincere and boundless joy at the destruction of the wilderness [and] every crashing tree”—you get a better idea of why it is that the only remnants of the expansive biodiverse prairies they found here are a few stray plants popping up in the ditches where the water drains off the dystopian hellscape we’ve made.

Reading Eirik the Red’s Saga last week, I got an unexpected bonus—a different telling of a story I had first encountered in 2016 in the Laxdaela Saga. It’s the story of the woman known as Aud the Deep-Minded, sometimes called Unn. A warrior’s daughter who wed the Viking conqueror of Dublin and, after his death, became a matriarchal leader of legend. She led her son and their people to Scotland, and when the son was killed, she built a ship—a kind of ark—in secret in the forest of Caithness. She loaded the knarr with valuables and a large retinue of fighting men under her command—first to Orkney, then the Faroe Islands, and finally to build a new community in western Iceland, where she famously landed thralls who had formerly been unfree.

Aud never gets her own saga, but she pops up all over the others. Her story provides a reminder that there are always paths to carve out zones of autonomy, even when the pirates are in charge. The animals that manage to make home in the negative space of the city teach a similar lesson. I wonder if, in one of those pockets of woods hidden below the overpasses, we might find someone building their own secret vessel in which to escape to a better tomorrow. Or if we might build our own.

Upcoming Appearances and Other Reading

This Wednesday, I’ll be rejoining my colleague Malka Older and futurists Jake Dunagan and Scott Smith for a post-election breakdown, Breaking Futures, live on YouTube at 2PM EST/8PM CET. It should be a fun and forward-looking conversation.

Two weeks from today, on November 17, I’ll be at the Texas Book Festival in Austin, in conversation with author and photographer Sarah Wilson and moderator Ray Brimble, talking about our books and the theme of “Earth, Memory and the Art of Connection,” 1:30-2:15 p.m. that Sunday at The Jones Center on Congress Ave. The Festival is a wonderful celebration of books that takes over downtown for the weekend, and there’s an amazing roster of folks coming to town. I hope to see some of you there.

Later in the month, I’ll be in Seattle at Elliott Bay on Nov. 21, and in conversation with Michelle Nijhuis at Powell’s in Portland on Nov. 22.

And as mentioned last time, I’m delighted to report that A Natural History of Empty Lots will be officially available in the UK (on January 9) and Australia (date to come).

Speaking of Michelle Nijhuis, thanks to her for this lovely coverage of A Natural History of Empty Lots in the Nov. 21 issue of The New York Review of Books (behind the paywall for now, but should be on the other side soon), and to Henry Wessells for this photographic proof (still waiting for my subscriber copy to arrive).

In other news, the Zoological Society of London and the World Wildlife Fund just published their 2024 update of the Living Planet Report, more sobering than ever. I was disappointed to see how much of the mainstream news coverage focused on scientific skepticism about the reliability of the numbers, rather than the core takeaway that even the estimates of planetary biodiversity loss at the low end of the range are break-the-glass indicators of our current trajectory.

For some windows into the emergence of fascism, and the truth and reconciliation that hopefully follows, check out Rebecca West’s 1945 report from the trial of William Joyce aka Lord Haw Haw, or Hannah Arendt’s original dispatches from the trial of Eichmann in Jerusalem, both in the archives of The New Yorker. You can also watch Arendt’s amazing, smoke-drenched black and white interview on Zur Person. Or avoid such subjects entirely, and tag along with John McPhee foraging with Euell Gibbons in 1968.

Enjoy the extra hour, and have a safe week.

I finally got a chance to read this. Thank you for the field notes! I enjoyed the hawk and the sounds of the Osprey and grackles. I used to live in south Austin and work at Woodward and hwy 71 so this post brought back so many memories.

I live in Capitol Hill Seattle now and just saw you will be at Elliott this week - I’m new to your work but I’ll try to stop by and say hi. 😊

Well!! I was looking out the window in the upstairs yoga room at Town Lake YMCA trying to move my surgically altered shoulders into a semblance of Warrior 2, with that fine view of the Independent (Jenga Tower) when it hit me: You've got the birds of prey aloft on the rising hot air currents due to our sick anthropocene climate, paired with the rising tide of fascism... and other dark chords. This, in addition to yet another new word I learned to day, premonitory. Which adds yet another ominous note in this election eve post. I'm on my way to the Vinland Sagas, bro.