Electric Jaguars and other fur-bearers

No. 170

Winter arrived in earnest here in the week leading up to the solstice. A weirdly flowery winter—a fortnight of rain at the beginning of December was followed by a cold snap and some gusty winds that finally bared the trees and carpeted the floors of the forest behind the old factories. But it hasn’t frozen, and when the rains cleared and the sun came back out, a surprising number of the native plants flowered in a last gasp of autumnal blooms. The lantana especially, with all the variant colors of a pack of Skittles, sometimes hugging up against the prickly pear. That and the buttery yellows of wild daisies, the inky indigo of wild sage, and the chalky white of the frost weed, which will soon be sweating surreal formations of ice.

When the skies are clear in winter here, the sunrise brings a rapid change in temperature that generates thick fogs on the urban river. Thick enough to hide the structures of the city from your view, and almost thick enough to muffle the sounds of downshifting trucks, departing 737s, and emergency responders. Our old dog Lupe, who has spent her entire life in this uncanny little valley at the edge of town, likes these sorts of mornings enough to venture farther on her old hips, and even jump like a pup when she sees the lead.

When we get out on our walks, we see lots of the overwintering birds—ospreys, pintails, and elusive arboreal songbirds whose names I do not yet know. The season also brings some of the year-round inhabitants out more conspicuously. There’s one pair of caracara we’ve seen almost every day, always flying north or south over the abandoned dairy plant, and a peregrine I’ve encountered three times in the past two weeks—perched on a telephone pole in the overgrown right of way behind the door factory, flying over the berm cloverleaf of the tollway bridge, and watching me from the metal sign that once advertised a trailer park called The Grove.

The weirdest seasonal arrival has been the Jaguars. Self-driving robot Jaguars that stick to the pavement, but move a lot like the predatory fur-bearers who live in the urban woods and come out at night to hunt the city. Taxis with no drivers, confirmation the sci-fi future of our childhoods has arrived in its true form, as faux-friendly and corporate as the ride a character would get in a Philip K. Dick story. Google’s current generation of Waymo cars are styled as crouched white crossbacks and covered with spinning electronic eyes, like Argus on the move, and totally silent, powered by batteries. The other day as I returned from a weekend run I came upon one laying in wait at the end of our street, obviously powered on, waiting for a fare to appear nearby in the way an animal patiently stalks its next meal.

Friday night in my phone feed the local news played a propaganda video from the company showing how one of the Jagbots had successfully evaded a scooter-riding human as she wiped out on the Drag. Trust us, they will not eat you, just some of your credit.

In August in San Francisco, residents of SoMa reported that the cars would take to a neighborhood parking lot after midnight and start honking at each other. The company said it was a programming glitch, but that’s just the kind of thing the wild canids do in the urban woods, especially in the frisk season of winter. I heard the foxes Thursday night, carrying on like cats trying to imitate coyotes.

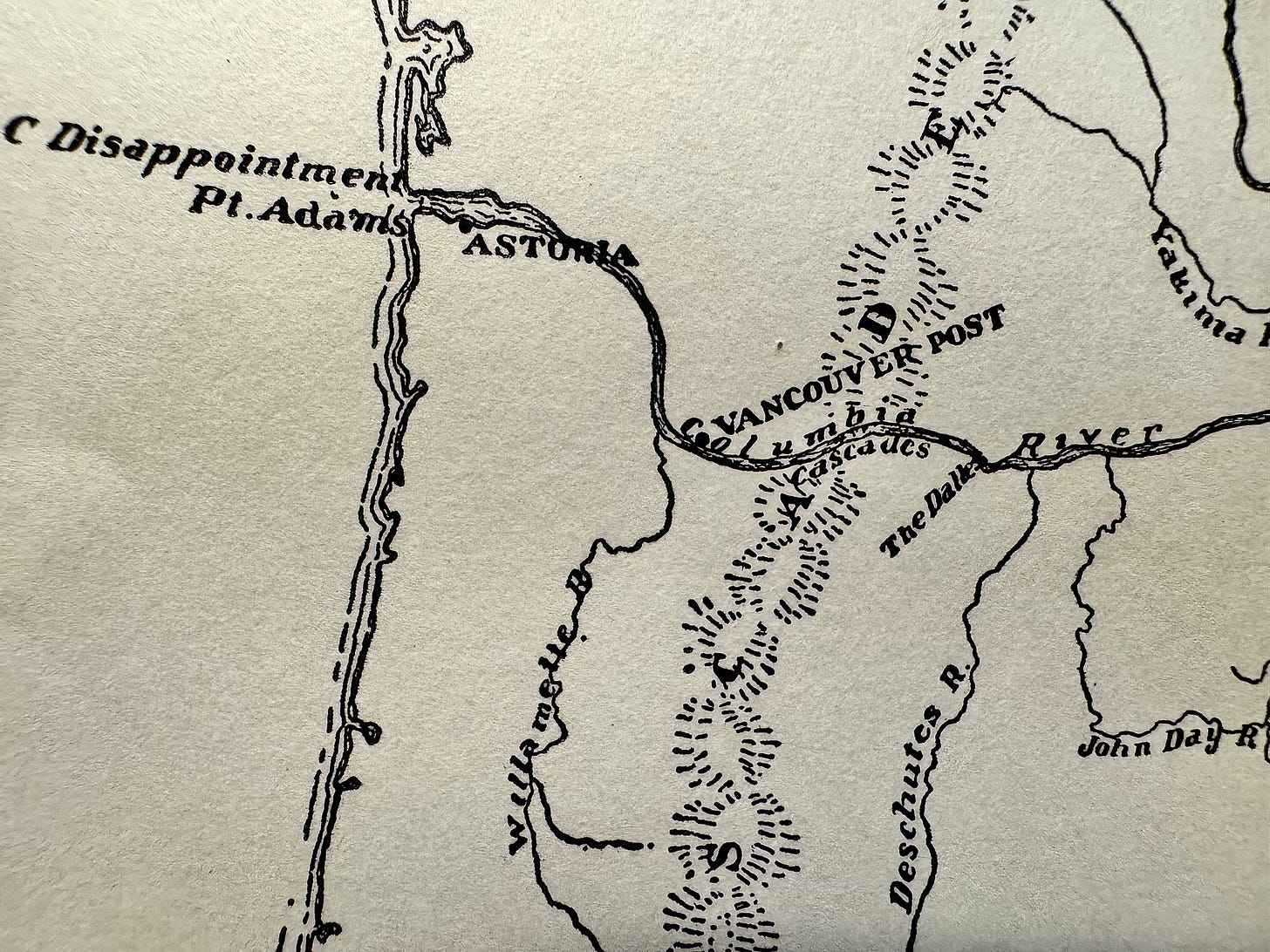

I’ve been reading a 101-year-old Christmas present over the past couple weeks, one I purchased as a thank you gift for a colleague and found myself hooked on reading before I ship it. It’s one of the earliest tomes of classic Americana the financial printers R.R. Donnelly & Sons would print in beautiful little editions with a fresh historical introduction and a report from the management to ship to their customers at the end of every year over the course of the long twentieth century. The 1923 selection was Adventures of the First Settlers on the Oregon or Columbia River, Alexander Ross’ memoir of establishing the first outposts of John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company at the mouth of the Columbia in 1810-13. As a corporate lawyer, I used to be on the mailing list to get one every year from Donnelly, while their main competitor would send free updated tomes compiling the federal securities laws.

The American library is well-stocked with first-person recollections of the colonization of the continent. Stories of where we came from, why we left, how we got here, what we found here, how we changed it, how it changed us. We don’t tend to give those sorts of stories much attention anymore, at least not as literary works, outside of certain sub-categories like captivity narratives. But I find they provide a powerful tool to better understand how we got to our current moment, as well as diverting stories.

The story Alexander Ross tells has all the elements of an epic adventure tale. It starts with the cinematic arrival of a dozen young Canadian management recruits at downtown Manhattan, transported in a giant bark canoe by an escort of singing Voyageurs and welcomed by a crowd of cheering luminaries, takes a long and harrowing journey around Cape Horn on a ship captained by an Ahab-like tyrant, has an idyllic and decadent sojourn in Hawaii, and then details over hundreds of pages all the mishaps, fears and failures of the group as they try to build their outposts and interact with the diverse Native American groups that surround them. As you read, you see that Ross and his colleagues were pretty useless as adventurers—they read as inexperienced paddlers, bad hunters, worse fishermen, clumsy lumbermen, and shoddy builders. They live off the food they bring with them across the sea, and if they run out, they starve unless they luck into the generosity of Natives or the appearance of a game animal too old to run away. They have guns, but they rarely use them. Because what they are really good at is making deals. And the book is really just a business memoir—the diary of a young exec who got hired to set up a new office and develop a strategic territory for the boss.

The expedition from corporate arrives in a frontier that you might reasonably expect to exist in some pre-capitalist state. But it becomes immediately apparent that the Native peoples of the region, on the coast and deep in the interior as the scouts penetrate further, were already habituated to trade in useful goods mediated by various forms of money. The guns only come out if you have something the traders want, and refuse to sell it at a price they will pay.

I read Adventures on the Oregon in a season when I found myself unable to stop thinking about the sobering statistics of October’s latest Living Planet Report from the World Wildlife Fund—that the average size of monitored wildlife populations on the planet has plummeted 73% since 1970 (with the steepest drops recorded in Latin America and the Caribbean (95%), Africa (76%) and Asia–Pacific (60%), followed by North America (39%) and Europe and Central Asia (35%)). The report made few headlines, and the coverage it did get mostly focused on skepticism about how accurate those numbers are, when even if you halved the numbers they would confirm a catastrophic and accelerating ecological imbalance we all know is unfolding before our eyes.

The North American fur trade began to become obsolete before the Civil War, but the industrial businesses it provided the protean model for take life from the land far more effectively. Having just flown over the densely industrialized Columbia River valley for the first time just a week before I picked up Ross’s story of its first Anglo-American settlers, it registered with me how rapidly that consumption of the land has taken place, and continues. As we enter the winter holidays we are told to consecrate to the idea of peace, in advance of a new year that seems consecrated to the resurgence of unrestrained dominion, I find myself fantasizing that the robot taxis and their progeny might help us see ourselves better through their alien eyes, wake up to the agency we each have to make peace with our own environment, and free ourselves in the process.

Winter Blooms

Thanks to John R. Platt at The Revelator and Earthbeat for including A Natural History of Empty Lots in his list of “20 Environmental Books to Inspire You in the Year Ahead,” calling it:

“Quite possibly the best ecology book I’ve ever read. An eye-opening memoir that has me looking for life — and often finding it — amidst the broken places in my suburban neighborhood.”

CJ Lotz Diego and Helen Bradshaw at Garden & Gun numbered the book among their “30+ Southern Books We Loved This Year” in a list of great works of regional nature and conservation writing. And fellow Austinite and garden guru Pam Penick had a lovely review this week on her site.

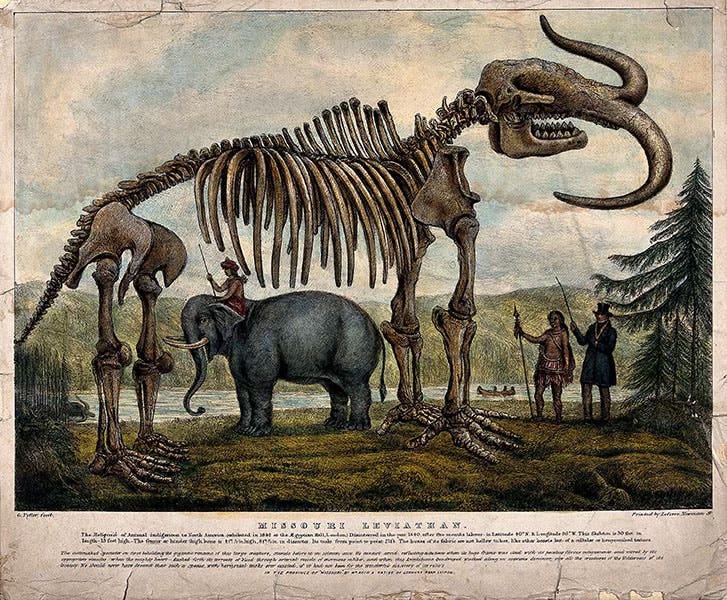

The best is when the booksellers say so, and it was wonderful to see Empty Lots on this year-end list from Leviathan Books in St. Louis, which also has the coolest logo: Albert Koch’s 1836 assembly of the Missouri Leviathan, which mixed the bones of multiple mammoths found in the muddy banks of the Mississippi to make a creature of legend.

I really enjoyed my conversation with Drew Maziasz on The Sound of Ideas from Ideastream Public Media (the NPR affiliate for Northeast Ohio), and the recording is now live on their site.

A Natural History of Empty Lots will be officially launched in the UK on January 9, so if you’re there, please consider yourself encouraged to spread the word — especially to your favorite booksellers.

My deep thanks to all of the folks who have supported the launch of the book in the U.S. and Canada this year, and to all of you who helped make it possible by checking out this newsletter and helping me see the potential of this material.

Congratulations to my wife, Agustina Rodriguez, for the ribbon cutting this month of her newest sculpture, “Cascade,” the centerpiece of a new public plaza near the terminal stop of Austin’s light rail network in Leander:

After finishing reading Empty Lots, filmmaker John Ewald shared this beautiful short on similar themes he shot on 16mm—”Titan Arum,” rich with images of wild flora overtaking our concrete ruins. Check it out:

In holiday news, San Antonio’s first-ever Krampus parade went on as planned last weekend without opening a portal to Hell, as had been forecasted by some angry locals.

Merry Christmas to those of you who celebrate it, and enjoy the quiet of the holidays even if you don’t. Get out for a winter walk on Christmas morning, and hear what the world sounds like when the machine momentarily stops.

skittle lantana, river fog smiles. love letters. thanks

"Garden and Gun" ranks up there with the great magazine titles I have heard, although surely not beating my top entry: Manure Manager, an actual glossy.