A Visitation from the Chuckle-Head

No. 161

I saw an apparition in the sky Wednesday night, almost close enough to reach, or so it felt.

It was 8:30 p.m., when the sun had just set. I was walking from our bedroom to the living room to fetch our daughter’s teddy bear. To go between rooms in our house requires, by design, stepping outside. The house is tucked at the edge of a pocket of woods along the urban river, behind a row of light factories and warehouses, an interzone where you see often see uncanny things on the move, especially at the crepuscular hour. An Anthropocene ecotone that has a way of making serendipity happen, usually in moments when you have forgotten its possibility.

Sometimes you encounter an animal right there on the patio, or at its edge—a coral snake, armadillo, opossum, toad or feral cat. Other times you see strange aircraft in the sky, flying low or high, aircraft that do not appear on the civilian flight tracker apps if you think to look. You may see a rogue campfire burning down in the forest, or hear human voices. On a Saturday you might hear the subsonics of outlaw EDM under the old bridge. Other nights you might hear an animal cry you have never encountered, like this still-unidentified creature in a tree by our bedroom door two Tuesdays ago, recorded on lightless video:

Wednesday night it was a bird, flying low just over the treetops and then just over my head. A night bird, but out at a moment when there was still enough ambient light to register its rich colors, which read red and brown and black. Almost like a little dragon, it seemed in the moment, but more likely a barred owl given its context and weird raptor proportions. It made me think how similarly the red-shouldered hawk and the barred owl have evolved. They both have a stubby, stocky form, which must be an ideal adaptation for avian interception of ground-crawling prey through the thickly branched canopy of the riparian woods where they can most commonly be found.

This week I read the news (which I first heard from Michelle Nijhuis’ excellent newsletter Conservation Works) that the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service has determined to proceed with its plan to cull the barred owls from the Pacific Northwest, an area where they are not native, and where their arrival is believed to have caused a plummeting of the population of the spotted owl, a species that had already been devastated by loss of habitat to the lumber business. I did a little digging, and found the 332-page document outlining the night hunting program in classic institutional prose:

Barred owls will be lured to the removal specialist using an amplified megaphone, or similar device, to broadcast digitally recorded barred owl calls, alternating with listening for responses. The calls and mix of calls are at the discretion of the removal specialist, but generally include single-note hoot, 2-phrase hoot, ascending hoot, and pair duet calls. Generally, removal specialists will call for about 15 minutes at a location before moving on if no barred owls are heard…

Lethal removal shall be done by shotgun of 20 gauge or larger bore, using non-toxic lead-substitute shot (e.g., Hevi-shot, steel). Lead shot may not be used. Rifles, pistols, or other firearms or methods are not authorized under this protocol unless explicitly approved by the Service for specific situations or occasions.

We recommend that shotguns be equipped with an attached night scope or other gunsight designed specifically for night use for accurate and precise aiming in dark or low light conditions (e.g., red dot sight mount). All shots must be directed at barred owls which are stationary on an unobstructed perch and present a full, frontal and unobstructed view. On-the-wing shots are not authorized under this protocol.

If barred owls are wounded, but not killed, every reasonable effort shall be made to locate any injured barred owl and euthanize it quickly and humanely. All personnel must be trained in field euthanasia and carry the needed equipment at all times during any removal attempt.

Any injury or death of a non-target species must be immediately reported to the designated Service contact.

The management plan also includes a fascinating discussion of how our alteration of the landscape facilitated the migration of barred owls, which evolved east of the Mississippi, to coastal Oregon and Washington—not through the removal of trees, but through their introduction into the once much more sparsely arbored great plans that separates East from West Coast.

In my new book I recount some of my encounters with barred owls in the East Austin edgelands, including my efforts, occasionally successful, to imitate their four-note call. For me, these mystical birds are a barometer of the ecological health of the pockets of urban woods around here, a state of wildness that seems to ebb and flow with the development of our fast-growing town, and the volume of human visitation into their domain. They are so much shier of us than the red-shouldered hawks who hunt the same territory during the day. Whenever I worry they are gone for good, I hear them again, and am relieved.

Sometimes one shows up on a trailcam, like a specter, giving you an idea of what the experience of them must be like for the animals they hunt. Seeing one on the move through the clear night sky with the naked eye, especially in one of those glimpses where you can’t really make a definitive ID, amplifies their alien nature, and the simple wonder.

The maps in Fish & Wildlife’s lethal management plan suggest barred owls may not even be native to this part of Texas, but they have been here for a long time, as evidenced by the entry on the species in George Finlay Simmons’ 1925 Birds of the Austin Region, which deemed them a “tolerably common resident, the most common of the larger owls,” often found in the river bottoms and heavily wooded draws, but rarely seen in urban shade trees the way the screech owls are. He also notes some of the other common names now lost: Crazy Owl, Bottom Owl, Old-Folks Owl, Chuckle-Head.

Barred owls do not do anything that resembles the activity we call work. They hunt at night, and rest during the day, a mode of living that is similar to most of the wild birds and mammals around us. Some are hunters, some are foragers, and some are both, as we once were. There are animals around us who do engage in a species of work, animals who even have the semblance of urban organization, like the harvester ants with their 150,000-member subterranean colonies, who clear dirt roads through the landscape and dispatch their workers to collect grain from the land and help the colony accumulate surplus, regulating their comings and goings in a pattern mathematically identical to TCP/IP.

On the North American holiday of Labor Day, as I’ve gotten older, I often find myself thinking how it is that we have come to live more like ants than apex predators. The answer seems fairly obvious: that it’s the price of our affluence, of our accumulation of ever-greater quantities of surplus extracted from nature that helps us not just survive, but prolong our lives, make them more comfortable and rich, and grow our species. But you can’t help but feel, if you are honest with yourself, something off about the way we live our days. I suspect most of it feel it in our bones, when the time comes to leave home and school and find paying work.

Anthropologists say that the pockets of humanity who survived into the modern era living more like our ancestors did, as hunters and foragers, were (and in a few cases are) objectively happier. Maybe you have to be an anthropologist to think so, but measured by the quantity of time available for leisure the evidence is compelling.

Labor Day’s origin, already somewhat lost a long century after its origin in the peak of the industrial revolution, is as a day that commemorates the laborers toil and service to the community. Maybe, in its idea of a Monday without work, it can also be a moment to think about how we might live differently. You don’t need to take the red pill to see through this pampered simulation we have built for ourselves. You just need to go outside, step off the pavement, and take note of the real life all around us. You might even bring some back with you.

Long Weekend Reading

More common around here than the barred owls at summer’s end are the creatures who are most definitely not native, but also seem naturalized in a way that no other species seems to mind (other than the technicians in charge of maintaining the cell towers where they like to nest). The monk parakeets are almost ubiquitous as our unusually wet August winds down, enjoying the abundant fruit of the mesquites, a tree the barred owls avoid. Their call is a lot harder for me to imitate, but they could learn to mimic me quite well.

This week I stumbled upon the story of how, while exploring the Orinoco River in Venezuela in 1800, Alexander von Humboldt met a parrot who was the only living speaker of the language of an Indigenous people whose population had otherwise been extinguished. Whether it really was a dead language seems to be a matter of debate. But true or not, the story tells a truth we can all intuit.

The owls have been hunting under an exceptionally beautiful sky this month, especially this week. Even in our light-polluted city, if you get up before dawn (or stay up all night) you can clearly see Mercury, Procyon, Mars, Jupiter and a few other bright stars there between the waning crescent moon and Orion. Thursday morning I saw another equally bright sparkle off to the edge of that tableau, which I later realized was Saturn. Uranus and Neptune are in the array, too, but for that you need magnification, or maybe darker skies than we have. More here.

Last Sunday’s NYT had a great piece on the beekeepers whose bees get to forage the bounty of the rewilded DMZ.

Also from South Korea, the country’s Constitutional Court ruled Thursday that the nation is legally compelled to do more to combat climate change. Kudos to the lawyers and plaintiffs who fought for that decision.

Over at The New Yorker, a top perfumer takes a whiff of the Gowanus Canal. And less snarkily, a consideration of the idea of “sea level,” and just how it is we measure it.

Coming Soon to an Empty Lot Near You

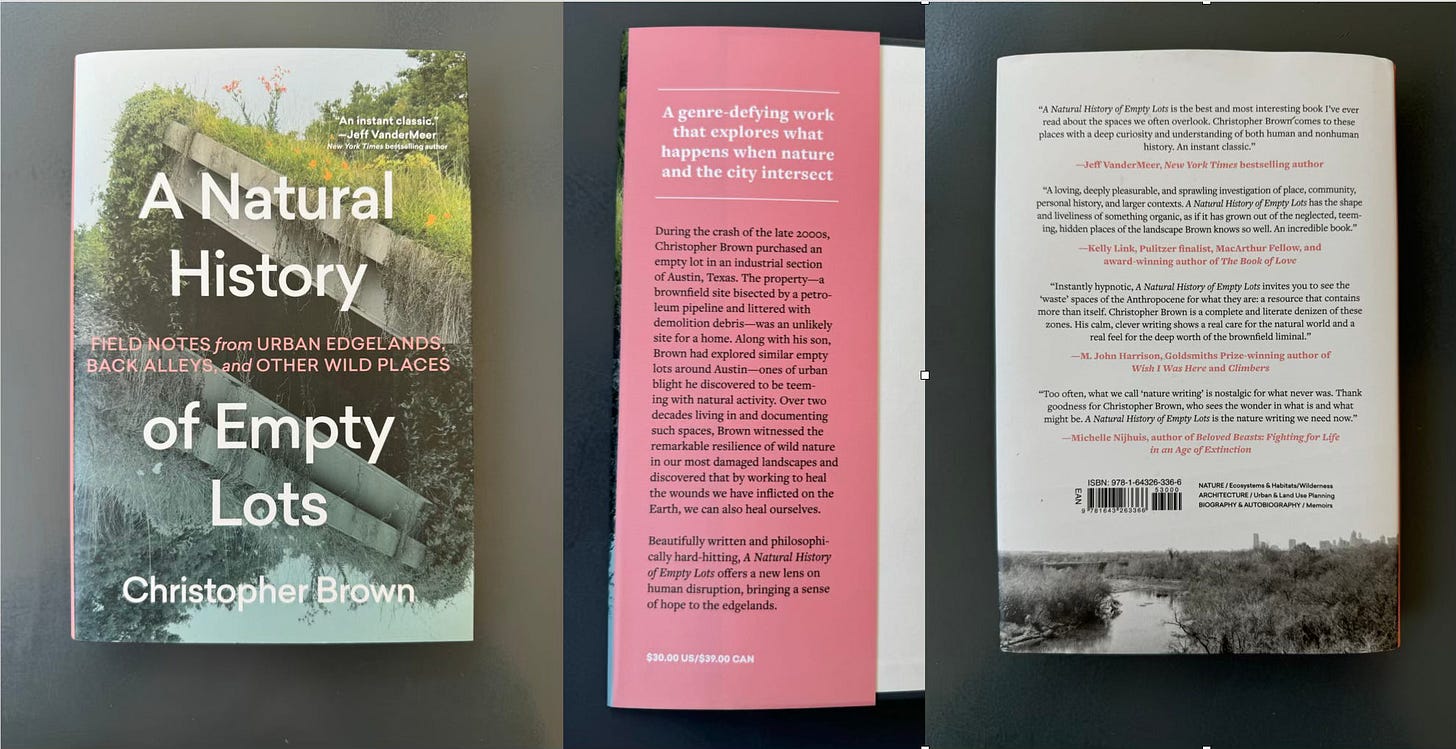

Looking closely the natural world as it exists in our cities and zones of agricultural production, and considering what that can teach us about our own lives and how we might live differently, is a core focus of my new book A Natural History of Empty Lots , which will be hitting the shelves two weeks from Tuesday, on September 17. Here’s what some of the early readers have had to say:

"A loving, deeply pleasurable, and sprawling investigation of place, community, personal history, and larger contexts. A Natural History of Empty Lots has the shape and liveliness of something organic, as if it has grown out of the neglected, teeming hidden places of the landscape Brown knows so well. An incredible book." — Kelly Link, Pulitzer finalist, MacArthur Fellow, and award-winning author of The Book of Love

"A Natural History of Empty Lots is the best and most interesting book I’ve ever read about the spaces we often overlook. Christopher Brown comes to these places with a deep curiosity and understanding of both human and nonhuman history. An instant classic." — Jeff VanderMeer, New York Times bestselling author of Annihilation

"Too often, what we call ‘nature writing’ is nostalgic for what never was. Thank goodness for Christopher Brown, who sees the wonder in what is and what might be. A Natural History of Empty Lots is the nature writing we need now." — Michelle Nijhuis, author of Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction

“Instantly hypnotic, A Natural History of Empty Lots invites you to see the ‘waste’ spaces of the Anthropocene for what they are: a resource that contains more than itself. Christopher Brown is a complete and literate denizen of these zones. His calm, clever writing shows a real care for the natural world, and a real feel for the deep worth of the brownfield liminal.” — M. John Harrison, Goldsmiths Prize-winning author of Wish I Was Here and Climbers

“Like flowers from broken asphalt this book is a surprise joy—in a time of anxiety, this is a meditation on how, to paraphrase the fictional Ian Malcolm, life finds a way." — Chuck Wendig, author of Wanderers and Black River Orchard

As mentioned last week, the dates for the Texas portion of the book tour for are coming together, and if any of these are near you, I hope you will join us—and invite your friends:

Wednesday, September 18, The Twig Bookshop, San Antonio, with Jennifer Bristol

Thursday, September 19, Book People, Austin, with Jesse Sublett

Thursday, September 26, The Wild Detectives, Dallas (Oak Cliff), with Bonnie Jo Stufflebeam

More to come on other launch events to follow. My publisher, Timber Press, has a preorder promotion underway here. And for those of you who have preordered and emailed me to get the print version of this newsletter I’m doing as my own promotion, I’m hoping to get those printed and in the mail by the end of this week (and maybe bring a few extras to Armadillocon next Saturday, September 7, where I will be reading and participating in a couple of panels).

Have a great week, and for those of you who have Monday off, enjoy your free day. Field Notes will likely be off next weekend as I meet some other deadlines.

Insightful statement here that resonated with me: "I often find myself thinking how it is that we have come to live more like ants than apex predators." And it seems we're continuing on this path of refinement where we operate a digital colony of ants.

As usual, Mr. Brown, a great morning read. Thanks! I like how you leave the USFW Barred Owl removal program unjudged for readers to draw their own conclusions. Dan Flores' tale, in Coyote America, of the many cruelties and outrages of the several iterations of what is today USDA Wildlife Services (what a misnomer!) I found almost too hard to read. But I, too, will leave other readers to judge. Ha.