Winter contrails

No. 189

Monday morning as I inched my way onto I-35 after dropping my daughter off at her sweet little school across from the abandoned shopping mall, I saw a dude walking along the shoulder of the northbound lanes, wrapped in a black blanket that blew in the wind every bit like a cloak he might have borrowed from one of Galadriel’s elven lieutenants circled around the fire behind the Home Depot. The guy was being followed by three police interceptors inching along behind him at the same pace, emergency lights running. My view was obscured as we passed under the 51st Street overpass, and when we emerged, the cops had disappeared. In the moment’s glance I could grab as I merged into the flow, I watched the hero continue his journey on the concrete ledge as if it were some mountain pass, the cloak animated with the brush strokes of the winter wind. Put one on the boards for the home team.

On our way to drop-off, the first grader and I discussed the new year’s resolution she had shared in her homework: “Toking to Birds.” That got me thinking about how we might go about making first contact, and with which species.

Winter is the season when the great-tailed grackles are especially easy to find. In the evening when I’m headed home from work they are often gathered on the ledges of the interstate’s upper deck during evening rush hour. Maybe they are looking for the pyramids that were once their home, when Moctezuma’s uncle Ahuizotl imported them to Central Mexico from their native habitat around Veracruz. They’ve only occupied Central Texas for a century or so. Thursday morning when I got my early departure for LAX, hundreds had filled the branches of the little landscaper trees that pretend to hide the parking garage. When grackles vocalize, it sometimes sounds like the squawk of a radio being tuned, and I’ve always wondered if you could imitate them with some sort of hand-held held electronics.

It’s also the season when the great blue herons return to their nests along the river behind our home, in the sliver of forest grown up in the floodplain between the tollway and the dam. There’s one tall old sycamore with a half-dozen nests that you can see from the end of our street. The tree grows from a trash-ridden bog at the base of a steep bluff, and was long hidden behind a cluster of windowless metal warehouses. But when they tore those down to make room for a planned development, the nests on the high branches were suddenly revealed, not that any of the young singles notice the amazing view while navigating their way from their cars to the bars. The first nest was re-occupied right after Thanksgiving, and by New Year’s they all looked to be. Those birds make strange noises too, more skronk than squawk, that I’ve sometimes thought could be easily replicated on a baritone sax with the right sort of free jazz energy.

Not far from that spot, a pair of black vultures has been hanging out a lot on this one particular telephone pole, above Rumpelstiltskin’s little shack behind the wind chime factory. They showed up right around Christmas, smudged with chalky white stains, cleaning each other and necking in the way only vultures can do, with those necks, heads and beaks designed to crawl up through a tear in your belly and pull out the the soft bits. They don’t really have a way for us to talk to them, but they seem very contented with the roadkill-rich habitat we’ve created for them.

And down in the woods, the barred owls seem especially active. It may be that the leafless winter canopy just makes it easier to spot them from a distance on our morning walks—I saw one every morning when I got down there this week. They are the only raptor I’ve ever managed to imitate well enough to elicit a response to my call, and they are the first bird Octavia and I saw when I carried her down into those same woods as a baby, so maybe I’ll try teaching her their call first. We might even summon Athena along the way.

New Year’s Roundup

Apologies to regular readers for what has been my longest gap between posts in the five years I’ve been writing this newsletter. We had an especially busy December, which culminated with an extended family journey to spread my father-in-law’s ashes at his hometown. The trip included an unplanned two-day layover in a Miami Airport business park Hyatt living off airline coupons, a challenging day getting over the Andes from Santiago to Mendoza by car, and a rough 24-hour journey back that included a 10-hour red eye in a cramped middle seat with the kid sprawled across my lap. I read Piglia on Borges most of the way, having gotten completely hooked while in-country, and able to read the Spanish more fluently thanks to the week of immersion. We had invaded Venezuela and kidnapped its president that morning, and the vibe at DFW as we re-entered the USA reminded me how, ever since 9/11, the return home is always the most anxiety-inducing part of the trip.

Thursday evening in my L.A. hotel, watching CNN as I got ready to head to a business dinner, I was momentarily confused by the way the Chyron-crowded splitscreen made me think that footage of the violent uprising in Iran was downtown Minneapolis. I had a flashback to this time 15 years ago, when my feed was full of scenes from the Arab Spring, while the old neon plant across the street was the secret staging ground for the local chapter of #Occupy. I thought the conflation of the two could make a great story, and soon started working on what became my first novel, Tropic of Kansas: a story about an uprising in the U.S. to take out a fascistic corporate government run by a charismatic CEO turned authoritarian president. As I imagined him at the time, a mix of Mitt Romney, John McCain, and Hugo Chavez. The way the story played out, it opens in a militarized Minnesota, where rebels have been fighting the government for years. It seemed so implausible at the time.

I hadn’t looked at or given much thought to that book in years. Writing a book is a lot like an exorcism, and the idea of re-reading one’s first novel is a bit like the idea of reading stuff you wrote in your high school yearbook. But I was curious enough to see how my Minnesota scenes written in 2013-14 compared to reality that I opened the file up on my flight home Saturday, and it was strange to see how what had felt deliberately surreal in the writing has come so much closer to the now. You can read the first three short chapters here at Reactor, if you’re interested.

Having worked so hard to imagine what real-world Minnesota Monkeywrenchers would be like, I got a big smile reading this weekend’s field report from Julie Bosman at the NYT on how some folks are using the winter ice as their ally in pranking the Southern boys they assume to be disproportionately represented behind the ICE masks. Even my cranky old Republican dad would have admired the detail of the locals using their pull-on cleats to get around on surfaces the Homelanders can’t handle, as he was a big fan of those.

Over the holidays we started watching long-form nature documentaries with our daughter, looking for video-based narratives that reward more patient observation. We settled on Nature, which proved to be one of the only old-school PBS documentary series that still had the pacing of the pre-digital era. We screened two amazing episodes, one about sea turtles and jaguars, and the other about the walrus, and they were each beautiful but also slightly sad, as the stories they told were stories of animals adapting to the ways we have altered their longtime habitats. I wrote about it for my friends at Aqueduct Press, the Seattle-based publisher of feminist science fiction, for their always-excellent year-end roundup of things to read, watch and listen to.

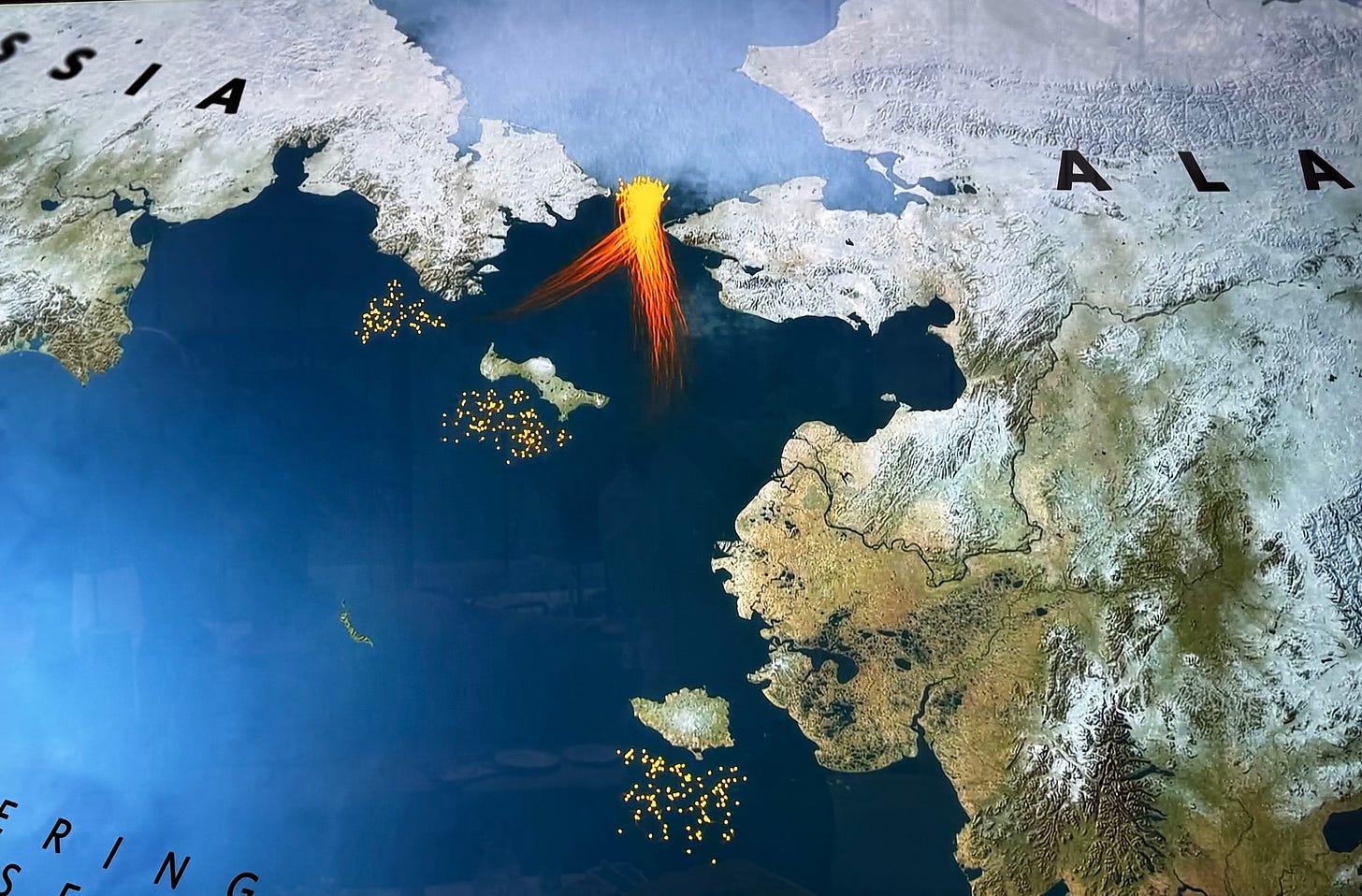

While part of the point of watching nature documentaries is seeing real life instead of computer imaging, the episode about the walrus included some graphics that reminded me how data-based machine visualization can powerfully complement real-world observation. I especially liked the below animated representation, which shows the females and pups making their run for the safety of the pack ice while the males hang back and get ready to head for the coastal beaches.

The punchline of the story is that the pack ice you can see at the center top, so critical to the way the walrus have long raised their young, is receding to a point where they may no longer be able to reach it.

Upcoming Appearances

If you’re in Austin, I’ll appearing this Thursday evening, January 22, at the Fusebox Artists Lab, to talk about my programming for this year’s festival, part of a new collaboration between Fusebox and the Texas Book Festival. I’ll be sharing more about that here soon—stay tuned.

If you’re in the Philadelphia area, on March 3 I’ll be appearing at the Philadelphia Flower Show.

More events coming up throughout the year, and I will share the details as they become available.

Stay safe, and have a great week.

Chris, your writing continues to amaze me years after becoming acquainted with it. I recognise its matter-of-factness while languishing in its poignancy. Thank you!

Our turkey vultures hiss, but I do not speak, and do not care to speak, their grunt-and-hiss language. However, I would like to be fluent in redtail hawk.

Keep writing. Does not have to be posted weekly or monthly. Your insights are always appreciated.