Volunteers of America

No. 181

This is the season when the right-of-way in front of our house reaches its most intensely feral state. We live at a double dead-end, where two secondary roads terminate at what used to be the edge of town, and every summer the sidewalks and chainlink fences are consumed by foliage. Much of it creeping vines—mustang grape, poison ivy, alamo vine and others—but there is also prickly pear and a cluster of agaves that have been holding their own. One just bloomed, shooting its flower spike fifteen feet above the crowd, the yellow traffic warning to turn (recently installed after the third time in a decade someone drove right through that fence) pointing right at it for emphasis. Chances are the plant is monocarpic, as are most agave species, and after this first and last reproductive burst it will die.

I walk out there every morning to retrieve our newspapers—one local and one national. An old habit that has matured into an anachronism, and an extra expense. But the better the digital versions get at near-real-time notices of what’s happening, the more I prefer the delay of reading yesterday’s news. It keeps the algorithms out of your head. Even as you can tell the digital edition now shapes the print content. The only part of the Times that feels untainted by the changed media environment is the obituaries, where the good ones still read like condensed novels.

Tuesday after dinner I made the mistake of reading one on my phone—Clay Risen’s obituary of the poet and critic David Slavitt, who also wrote popular fiction as Henry Sutton (among other pen names). It was suitably diverting, recounting the life of an author from the good old days when there was an actual mass market for mass market paperbacks. When I got to the end, the phone app served up the genteel variant of clickbait pictured below—a Rorschach of our damaged Zeitgeist that held my attention for a moment, and then got me to put my phone away.

It was a reminder of why I spend my mornings looking for signs of real life in places like the patch of grass next to the onramp (not just because our new puppy, who our daughter named Fifi, needs a walk).

The deserted traffic island I used to explore regularly with our older dogs is gone now, filled with a concrete parking garage that looks like a military fortification and the apartments and offices being built around it. The other day Fifi and I found ourselves walking past there anyway, around its east end and up the grade of the engineered berm that supports the tollway onramp. Where, to our surprise, we came upon a wildflower I had never noticed before—yellow-puff blooming in the expanse of recently mowed Bermuda grass just inside the guardrail.

Neptunia lutea is a native, one of the species that does well in areas that the botanists describe as “disturbed,” usually meaning environments whose previous ecological diversity has been heavily damaged by us. It’s a ground crawler that knows how to find its way to the light, staying low enough to evade the blades of the mower. A plant that doesn’t compete so much as find the space that’s left, even if it’s already crowded.

It’s also a sensitive plant. If you touch it, it will visibly recoil, closing its fern-like leaves. Here’s a video:

The scientists don’t seem to know the evolutionary purpose of this kind of rapid plant movement. It may be an adaptation to deter mammalian foragers or insects, a strategy to survive prairie fires, or a way to hold out in spots thick with other plants.

Neptunia is not the only sensitive briar we have around here. A couple blocks from where Fifi and I found the yellow-puff, a patch of hot pink powderpuff mimosa has been established for several years that we’ve observed, in a low wet spot between the driveway of a motor oil distributor and the unmowed lawn of an abandoned lighting factory. The yellow-puff reminded us, so we walked down there the next day, and the Mimosa was also in bloom, with flowers like hot summer candy.

The field guides suggest the easiest places to find sensitive briar are near bodies of water, especially stream banks and the edges of lakes. Yellow-puff’s genus, Neptunia, gets its name from the aquatic habitat of some of the species. Those observations made me wonder whether the urban variants we see around here are adapting to the engineered watershed, in the same way the cottonwoods grow to high-rise heights around the mouths of drainage pipes.

Saturday morning Fifi and I went back to investigate that theory, on the third day of a four-day rain. It seemed to hold up to closer observation of the Anthropocene topography—our neighborhood Mimosa occupies a depression between two bulldozer-flat industrial sites, next to a drainage ditch along a major thoroughfare. Similarly, we found Neptunia growing where the first flush of water runs off the pavement and onto the berm. The thickest patch was in the median between onramp and offramp, where the slope directs the largest quantity of runoff. Walking there we noticed another water-loving ground crawler creeping its way through the construction fence along the subtly sloped edge of another off-ramp: frogfruit, a plant whose common name tells you what kinds of conditions it prefers.

Friday’s July 4 print edition of the Times had an especially old school feature: The Declaration of Independence on the back page of the front section. It made it unusually readable, and I was struck by the conflation of nature and the divine order of things in the opening recitation that grounds the argument for human liberty and equality in “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God”—something different than “natural law,” especially in the way it abstracts the deity as an expression of observable nature.

Turns out a number of historians have noted that phrasing, attributing it to the deism of principal author Thomas Jefferson. Reading about Jefferson’s religious beliefs, or lack thereof, got me to finally click through some links about presidential perfume preferences in the era before long showers. No one seems to know if Jefferson wore a scent, but they do know Bay Rum was especially popular. My search led to an article about how Jefferson loved the fragrances of a good flower garden, and to the revelation that if you ask Google about his 1785 remark in a letter to a friend that the “blood of tyrants” is liberty’s natural fertilizer, you will get an entire page of links selling you right-wing T-shirts.

The native wildflowers that volunteer by the sides of our roads are a persistent reminder that the diverse life that was here before European colonization has not been completely erased. The resilience of those species always makes me think how easy it would be to help bring some of that biodiversity back with just a little bit of stewardship, and how we would find that repairing our damaged relationship with the land would help us remedy some of the broken things in the human community. Getting there will probably take a different species of volunteers.

The Roundup

Our thoughts this weekend are with our neighbors in the Hill Country, and especially the young summer campers and their families. My wife attended one of those camps as a girl. In East Austin we have been lucky thus far, as the dams along the Colorado and the half-empty lakes seem ready to accommodate the inundation, but our friends and neighbors in the northwest suburbs have been not been as lucky.

The rain here started Thursday morning, and continued until dinnertime Saturday, in a season that is usually quite dry. I woke Saturday to a slow drip on my head at 4 a.m., from the crack around a light fixture, hazard of living in a subterranean house covered with an experimental green roof. By 6 p.m., the river finally came up above its banks, and filled the floodplain right up to the base of the bluff we live on. On my way back from a Saturday night hardware store run for leak mitigation provisions, I checked out the river where it empties out of Longhorn Dam, and it was pretty epic:

The gates on that dam are manually operated, and when I stopped the operators from the municipal power company were out getting ready to adjust them as needed. I took it as a good sign that the guys I saw were relaxed and having some laughs.

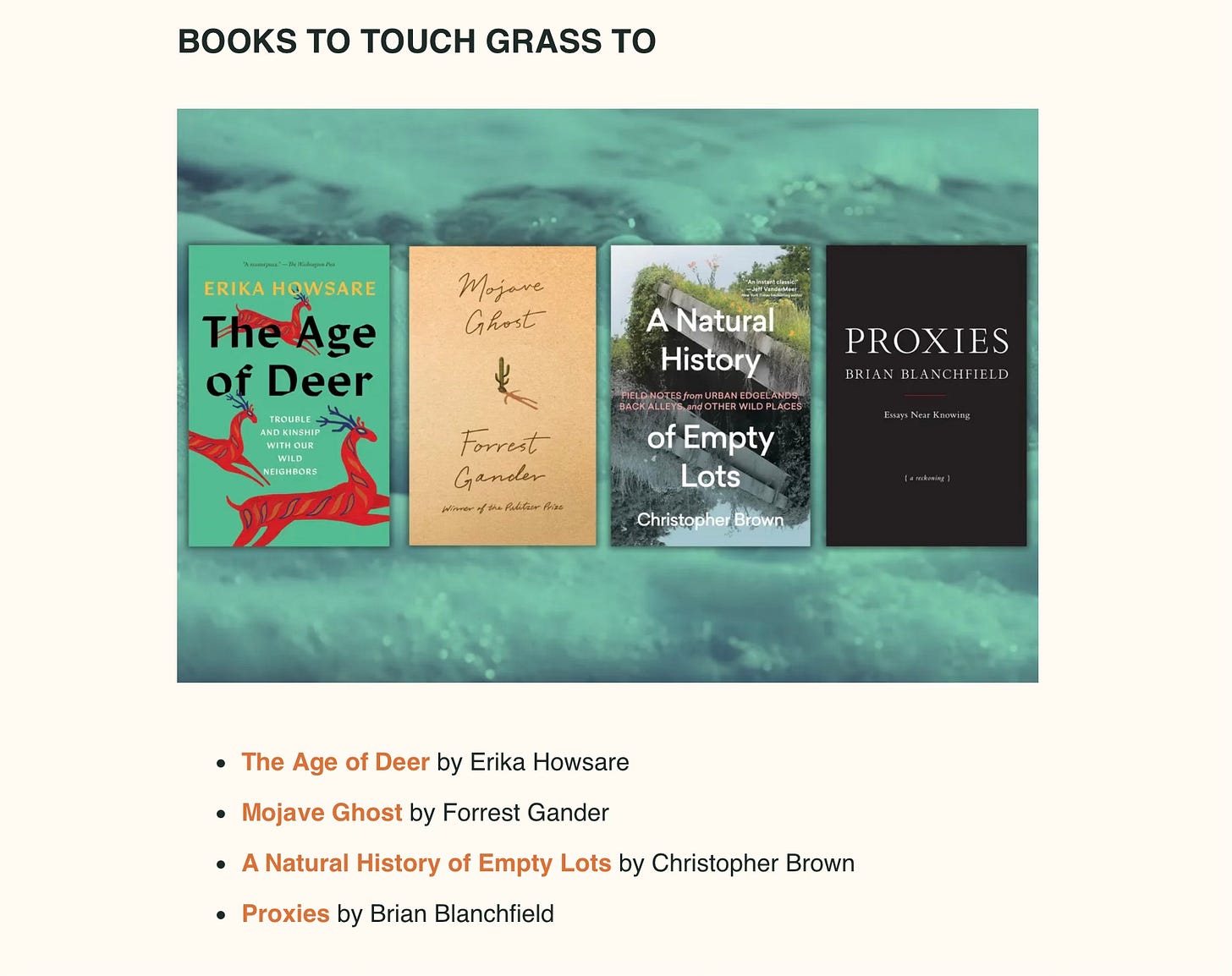

Thanks to Daisy Alioto and the team at Dirt for including Empty Lots in their summer reading list, in my favorite category name ever:

Congratulations to Field Notes friend Henry Wessells on the publication of a new edition of his short story collection Another Green World, in a beautifully designed paperback edition that arrived in this week’s mail with blurbs from Guy Davenport, Joanne McNeil, and Guy Davenport. Also in this week’s mail was a book I was lucky to blurb (alongside some greats including Jonathan Lethem and Cal Flyn)—Joanna Pocock’s Greyhound. And I’m excited to get my hands on Ed Park’s new collection, An Oral History of Atlantis, coming out July 29.

Evidently we’ve been land snorkeling and didn’t know that’s what it was.

In archaeology news, evidence that the city-state of Çatalhöyük 9,000 years ago was a matriarchy.

In secret North American history, they found a runestone in Ontario.

And in surprising environmental news, a long read on how Los Angeles learned to consume less water, even as it kept growing.

Monday’s Austin American-Statesman had a great story from Michael Barnes about the 3 boys from Abilene who paddled the entire length of the Colorado River in 1937—and again in 1991.

In other paddling news, experimental archaeologists in Japan got their Thor Heyerdahl on, chopped down a big cedar tree with traditional tools, made a dugout canoe, and demonstrated how far earlier humans could get in such simple watercraft across the expansive Pacific. (The videos at the link make a good case for how the digital paper can be better.)

“From economy of occupation to economy of genocide”—the cogently argued report of UN Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese on corporate capitalism and ethnic cleansing, published Monday.

Lastly, it turns out the original title of this Jefferson Airplane song that regularly earworms its way into my head was “Volunteers of Amerika.”

Field Notes will be on holiday the next two weekends, back in late July. Stay safe.

I still feel taken aback when I read of another patch of greenery, well-known over the past few years of Field Notes, (ie 'the deserted traffic island I used to explore') that has succumbed to the concrete. That's how I felt when I read A Natural History of Empty Lots: of course I knew they were eyeing the area to "develop" but I had kept the reality of it at bay... so it's revitalising to see the flowers coming back, again.

Enjoyed this post. Now I know why the pink puff sensitive plant on the side of the house is growing there...it is under an outside hose faucet.

And thank you for the short clip of the Colorado river on the east side...I had not seen any footage of the river on the local t.v. channels and was wondering what it was doing after all this rain.