The vultures of SXSW

Thursday morning I walked our infant daughter into her first ever scene of death in nature. Not the sort of unicorns and rainbows thing one is supposed to highlight, but nature in that respect is kind of like the television programming of my analog youth—you get whatever happens to be on that day.

I am pretty sure that in my youth, we didn’t have vultures living off the human landscape the way we do now. It was in the late 80s that I started to see them more often in the Midwest where I grew up. They started to appear over the interstates, cruising the thermals, waiting for new roadkill. Not a bad adaptation.

The raptors seemed to learn a similar trick not long after. Hawks, mainly, who hunt the mammals of the field, and have learned that one of the best places for them to do so is in the rights of way we have drawn through the land. They started to appear in bare trees and fenceposts along the high-speed roads that move people and product on the overland route through flyover country, patiently waiting for the next wingless critter to try to cross the pavement. Now they are everywhere. In the stretch of the Kansas turnpike that goes through the beautiful barren grasslands of the Flint Hills, there are more hawks than houses, or mile markers.

Where we live, they have adapted to similar conditions in the urban periphery. Edgeland hawks, who nest in the pockets of woods the city has neglected to pave, for now, and hunt in two worlds—the groves and riverbanks of the undevelopable floodplain, and the concrete convergence of all the roads that funnel the eastern half of the city onto the main bridge that crosses the Colorado in the direction of Bastrop and Houston. There’s an abandoned remnant of one of those roads on the empty lot next to our place, the path to an old ferry landing. The telephone poles still line that right of way, carrying packets of data instead of produce. And many afternoons when I step out of my trailer office in the front yard, I see a hawk up there looking out over the field behind the door factory, waiting for its afternoon snack to reveal itself in the zone of vulnerability we made.

In January, when our son and daughter-in-law were home visiting for New Year’s, we saw a mated pair sitting up there, like some special totemic blessing of their fresh union.

In February, I started spotting hawks’ nests for the first time. This is the season when all the birds are preparing nests and getting ready to welcome new young. There are only a few early buddings of foliage in the trees, which makes it easy to see the big found object aeries up there beyond the reach of any naked ape, in spots where even fancy cameras can’t really reach. I saw the first one about a month ago, walking with the baby on my back, just as the hawk alighted in the crook of one of the big cottonwoods that grow tall where at the municipal drainage pipe empties the runoff behind our house.

Like the cardinals who make their smaller nests closer to the house, and sometimes on it, this red-shouldered hawk had used some kind of industrial plastic fragments from this Anthropocene habitat to better insulate its home. The other day I saw the same hawk carrying a load of big sticks back there, while I chatted with the crew working on the house next door.

I saw the next one while walking the dogs on the street. It was one of the hawks I often see perched on the tall lampposts by the onramp, taking advantage of the traffic-funneling Texas cloverleaf the engineers built when this area was redeveloped as an “industrial park.” They say the red-shouldered hawks occupy the same territory for many generations, and I wonder if they moved here then, or if they’ve been here longer. Those roads were trails before, converging at the ancient low water crossing that now runs under the tollway, not far from the overlook where some say a Spanish fort guarded this far perimeter of the Castilian empire, on a site now buried in our trash.

Just a few days earlier, on a quiet Sunday morning, I had seen a hawk—maybe the same one—catching its kill in the mowed field behind the machine lubricant distribution hub a block away, right by one of those little tanker trucks proudly labeled NEW MOTOR OIL. After a while you start to notice their motion in your periphery, even if they don’t always give you and their neighbors a heads up with that trademark scree the mockingbirds have copied so well.

This nest was in a traffic island—a tiny strand of trees on the triangular parcel of land where three of those roads converge at base of the onramp.

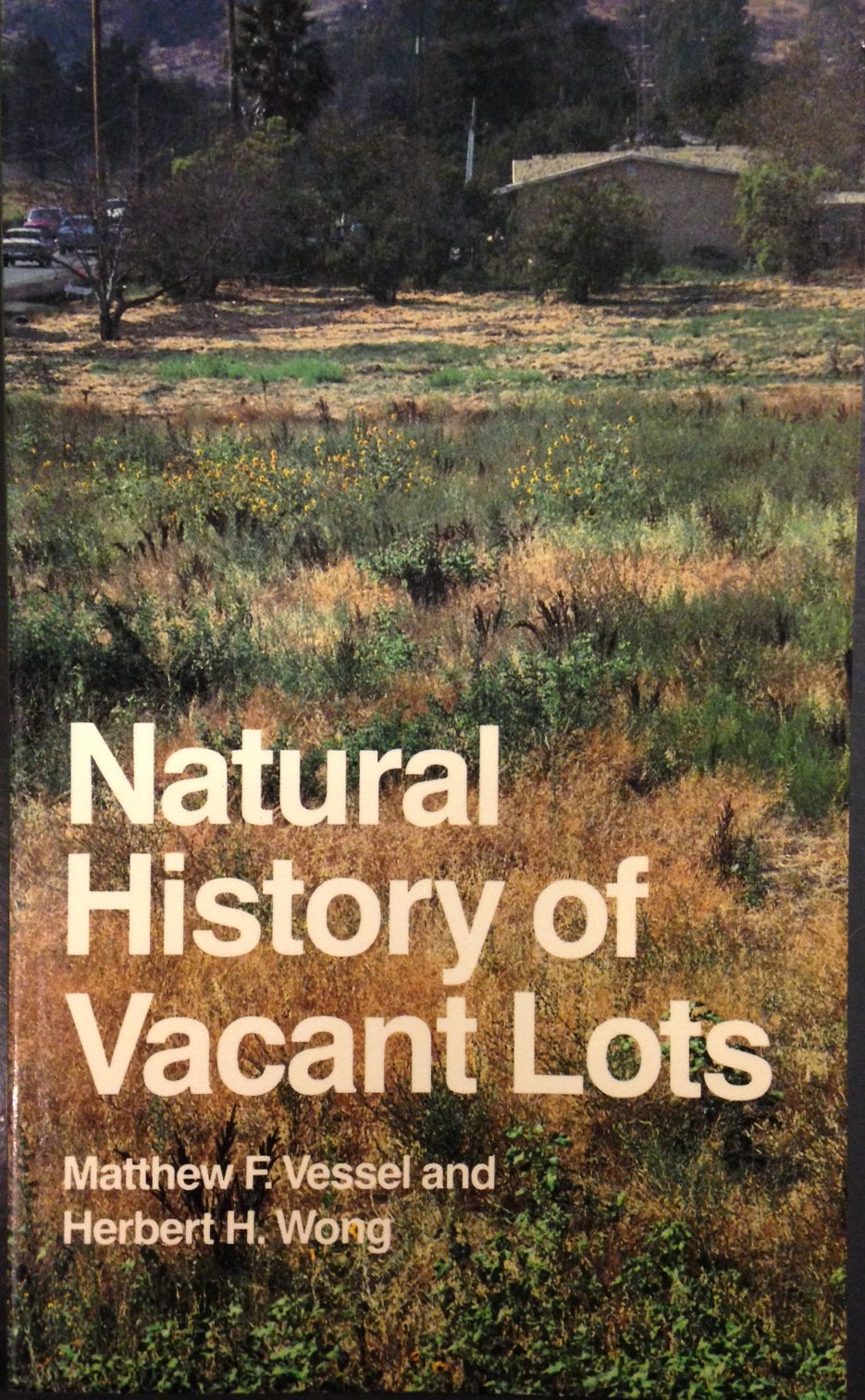

One of my favorite novels, it may not surprise you hear, is about a guy who gets marooned on a deserted traffic island. I’ve always gravitated to these little pockets of urban negative space. I grew up exploring them, the remnants of woods that got left behind by the developers and roadbuilders, the places where wonder and our connection to wild nature, or what’s left of it, are allowed to persist in the city.

On Tuesday I decided to explore the traffic island from the inside. I have been walking past that spot for years, never really giving it much notice, other than the tents I would sometimes see pitched back there, hiding in plain sight.

The woods are at the edge of a bigger, occasionally mowed lot between old industrial buildings that’s fenced in on one side. A basketball hoop stands in the middle of the roadside field, ruin of some prior tenants whose memory has been otherwise erased. They put a new sign up there at the beginning of the year, advertising the lot’s imminent transformation into that most wonderfully oxymoronic of land uses: CREATIVE OFFICE. The municipal bikeway parallels the adjacent road, the one that used to be named after Lance before his banishment, and on weekends the lane fills with affluent men peacocking in spandex.

Right after the sidewalk ends, and all that’s left is the high-speed off ramp where the cars and trucks come hurtling off the tollway, hides the woodland stand. Not a place anyone would want to walk. But when you do, you can see the trails of small animals under the fence, the complex mounds of the indigenous ants made from the alien dirt the road crews left at the shoulder, the native plants eking out an unmowed existence in the margins.

Tuesday I decided to investigate the island from the other side, the street that hems it in from the north. No fence there. Just some abandoned Morton buildings, with signs warning NO IDLING, and a flag so tattered by time and elements that the stars have fallen out.

The last tenant there had a business recycling the grease generated by restaurants. Now even that spot is going back to wild, even as you know what’s really happening is it’s about to get redeveloped, the beat-up remains of the interior offices strewn about the parking lot, with some weird small engine leaned up against the outdoor planter that has been taken over by prickly pear and retama. The path into the woods was marked was a discarded desk calendar from ThyssenKrupp, the lords of metal who armored the German war machine. Turns out the business started with a 16th century entrepreneur who redeveloped empty lots cleared by the Black Death.

The old onramp beyond that is closed now in favor of the new tollway path. And if you walk past the construction barriers, you find the remains of a path made by men, right by a thick bush bearing big scarlet berries. Maybe that’s from the Ruhr, too.

If you follow the path, you find two small drifter camps, both evidently abandoned. Shelters made from found materials, including industrial tarps used as lean-tos. Not unlike the hawks, in a way. Except that the hawks don’t leave all those empties behind.

I was reminded of this time last year, when I volunteered for the local homeless count, and at daybreak we checked out another traffic island across the river by the branch library, and found an entire village of such abandoned shelters, some of which looked to have been there for years. We also found little shanty towns packed in under the little bridges behind the strip mall, on one of the busiest streets in town, many of the occupants teenage kids. When you participate in a project like that, you leave with a certainty that the count grossly underestimates the real number of people living outside, hiding just outside your view, sometimes in the same places the wildlife hides. And, at least if you are the sort who writes dystopian novels, you get the sense that you are seeing one of those unevenly distributed futures, where the rights of ways and empty lots become involuntary refugee camps for those displaced by our slow collapse.

Maybe it’s this weird zone I live in, but over the last decade I’ve been noticing how the things one sees in post-apocalyptic cinema and the things one sees roaming the contemporary American landscape have started to look so much the same. The only difference is that, in real life, nature seems much more ready to retake whatever space we leave.

When the baby and I walked the dogs down to the riverbank Thursday morning, on the rocky beach that not too long ago was a place where they dredged gravel, a dozen black vultures had gathered at the waterline a couple hundred yards away, in the direction of the rising sun. We walked down to check it out. Black vultures are weird birds, more social than the turkey vultures you see up north, and more like tricksters. So I was wary of entering their space with the baby on my back. But that was where we were headed anyway, and they moved to a bare tree as we approached, and we came upon their morning snack. The hairless and color-bleached body of what looked to be a young coyote left behind by the receding waters of the dam. I don’t think our curious girl even noticed it, and we walked on, to where the more baby-friendly bluebonnets were popping in the gravel.

The news the next afternoon that they officially cancelled SXSW was greeted with pockets of wry celebration by some longtime locals tired of the city’s commercialization as venue for big money festivals designed to make capitalism fun. But looming behind that are more complex feelings, the same kinds of feelings that underly the article I saw in the new LRB this week about whether it is OK to have kids in these uncertain times. I suspect the fear of plague that has caused a run on hand sanitizer is only partly about the fear of this particular bug. Lurking behind it is the deeper fear generated by our underacknowledged awareness that we have gotten way out of balance with nature. A fear of the human die-off we worry we have tempted nature to finally bring. And behind that, the weird sense, evident in some of our freshest science fictions, that life on the other side of whatever is coming will be better—for those who make it.

The thriving of vultures in the 21st century city is sure evidence of how much death we generate for others, not just the pangolins on sale in the Chinese wild meat markets. Something like sixty percent of the wildlife population of the world has been decimated in my lifetime, a statistic that is so astonishing when you really think about it that you know what we are doing is unsustainable. We worry that nature has been incubating its revenge, probably from its mutation of some seed we planted in the exercise of our arrogant dominion—a notion that lurks behind most of our scary movies about plague, like the hilarious one I streamed this week. We worry that the future of the city is an empty lot. That the post-apocalyptic movies of your youth are visions of what the world wants to be.

My son and daughter-in-law are in Seoul, working their young people’s jobs in plague time, with masks on 12 hours a day as primitive prophylactic against deadly pandemic. Parenthood in a world that has lost the idea of a promising future is not without its anxieties.

But what the vultures remind us is that nature has its own ways of regulating our hubris. Trying to outthink it is a fool’s game. It has its own plan for you, even if it’s a random one. And no matter what your inner Cormac McCarthy might tell you about the long winter that’s coming, the bluebonnets coming up in the old gravel pit remind you that there’s always another springtime.

This week’s bonus videos include a Saturday leap day fox, and a few midnight coyotes. These videos are especially awesome with the sound up—something about the sound of those padded feet crunching the leaf litter brings out the real.