The redbirds of May Day

Cardinals are not one of the birds you get excited about. They are a common songbird that has always been nearby my entire life, among the easiest to identify for the same reason the Texans often just call them “redbirds.” They are especially common here in our yard in springtime. In the morning you hear their chorus, and all day long you see them getting busy. I just read that they are one of the only North American songbirds in which the female sings as well as the male, perhaps telling the male when it’s time to bring the food. No wonder they fit in so well in our space.

It is only more recently that I have come to appreciate what exceptional Anthropocene adapters the cardinals are. I noticed the nests before I understood who made them. The first one I found was in the branches of one of the bois d’arc trees that grows along our front path. A beautifully shaped little shelter of twigs and dried grass, the perfect size to hold in the palm of your hand. But then I noticed the plastic—fragments of some transparent industrial material used to better insulate the nest.

Such materials are in abundant supply around here. Our house occupies a spot where the interstitial wilderness of the urban woods is on one side, and the other side is dominated by light industrial uses—a door factory, a custom lighting studio, the county housing service’s staging facility, a gypsum yard, and a huge dairy plant. Those places generate lots of little pieces of trash, the kinds of things the guys who work there would not think worth capturing. Mostly, they are fragments of the materials we use to pack things for shipping, and also the materials we use to package the things we consume—to-go bags and the cellophane wrappers of cigarettes. When discarded, they collect in the street, up against the fences, and blow into our yard when the winds are right.

I never would have considered that the existence of these tiny byproducts of the factories would provide some of the birds that share our space with an advantage in the game of survival. But as I started to pay more attention over the decade we have lived here, I noticed that I never found a cardinal nest without such materials. And I noticed that there seemed to be more cardinals every year.

The bird guides tell you that cardinals will use “rags and other available materials” for their nests. Our redbirds have the choice of the full array of available materials. And they choose Tyvek®.

When we first installed our green roof, our friends from the Wildflower Center planted some cross vine along the edges that frame the little canyon that divides our sleeping area from the living area, a divide that occupies the space formerly taken by the petroleum transmission pipeline that used to to bisect this lot. I wanted the house to achieve a post-apocalyptic aesthetic, a sense of nature taking over the ruins. My wife wanted to cultivate natural Texas beauty. It took a couple of years for the vines to adapt to this weird space, a bed of growing medium surrounded by modernist planes of steel and glass. But when they did, they flourished, especially in the spots where the afternoon sun shines.

The cross vine is a native plant, with a bold orange-red trumpet flower. When the hummingbirds show up, as they have in full force this week, they show you how perfectly those flowers have adapted to those birds. They fit together like plug and receptor. The vines bloom in continuous cycles with the periodic bursts of rain we get here, exploding with color when the sun comes out after the storm. They especially love the spring and fall.

The stems of the cross vine grow thick with time. Not mustang vine thick, but close—thick enough to develop a skin more like bark, and the structural rigidity that comes with that. The glass that frames one side of our living room is fifteen to twenty-plus feet high, and the vines now hang down in a thick lattice half that height, at least in the areas where there is full sun for long parts of the day. There are other native vines mixed in there, like Virginia creeper, which help build all the interconnections that create a naturally occurring structural integrity. But they are still just hanging in the air. When the wind comes, you hear them flapping against the windows. You wouldn’t think it’s the ideal foundation on which to build a shelter. But that’s exactly what the cardinals do.

It’s just in the past few years the cardinals started to nest in those vines. It’s not hard to notice, from the inside. It’s like looking into one of those ant farms that were popular when I was a kid. They attach the nests to two or more adjacent hanging vines, in the space between the vines and the window, a gap of a few inches. From the outside, you can bet they only see reflections, as evidenced by the titmouse that has been attacking its reflection here for the past year—or was, until the cardinals came back this spring to nest. They seem to use the nests for a season, and leave them.

Last year, there were four such nests by our living room. One Saturday afternoon when Agustina was working there, she saw two fledglings fall to the pavement. She was alarmed, until she saw the parents fly up. They demonstrated to the fledglings how to move their wings. And then they all flew off into the nearby trees where the woods begin at the top of the bluff, maybe fifty feet away.

This past month one pair nested right over our bedroom door. From her crib, our infant daughter has been able to see their little heads popping up to be fed.

Our small dipping pool is chlorine-free, using a system that makes it like fresh water. The water flows over the negative edge in a constant circulation. We did not know when designing this that it would work as a giant modernist bird bath. But birds love the sound of the running water, and the water is clean. Soon the teen bird pool parties will begin. An accidental adaptation, but one that teaches that the more you design along the same lines as the natural environment, the more your habitat will allow sharing your space with other species.

It’s not as utopian as it sounds. Last week the cardinals above the bedroom stopped showing up. Disappeared. Gone to Croatan. We look up at those vines, and wonder who might have been able to get in there and get after those babies. A couple of years ago one nest was in the less sturdy frog fruit hanging down over our front door. After a couple of weeks, it partially collapsed, and was hanging there sideways, one little egg clearly visible, until it finally fell to the concrete below. Trial and error. Adaptation.

This year as winter ended and spring began, I noticed that the red-shouldered hawks who rule the woods from the high branches of the tall cottonwoods along the river and the tall pecans of the alluvial plains above also use the available industrial materials in their nests.

There are humans who employ similar adaptations—the men living outside in these woods, who collect bigger fragments and make their own shelters. A few years ago I came upon a perfectly constructed teepee made from the alien bamboo that grows along the right of way behind the door factory and a big sheet of industrial fabric printed with the logo of some exotic aviation-related brand. In the overgrown traffic island I explored earlier this season, I found two shelters made of similar materials, elaborate lean-tos that had taken on some of the characteristics of houses.

I have seen fewer of those this year, since the state set aside a big parcel of public land across the river for an open camp site, after the municipal public camping prohibitions were repealed and the homeless came out of the woods. A while back there was a story in the news about how the occupants of the camp have formed their own government. Direct democracy, in an unlikely temporary autonomous zone off the frontage road.

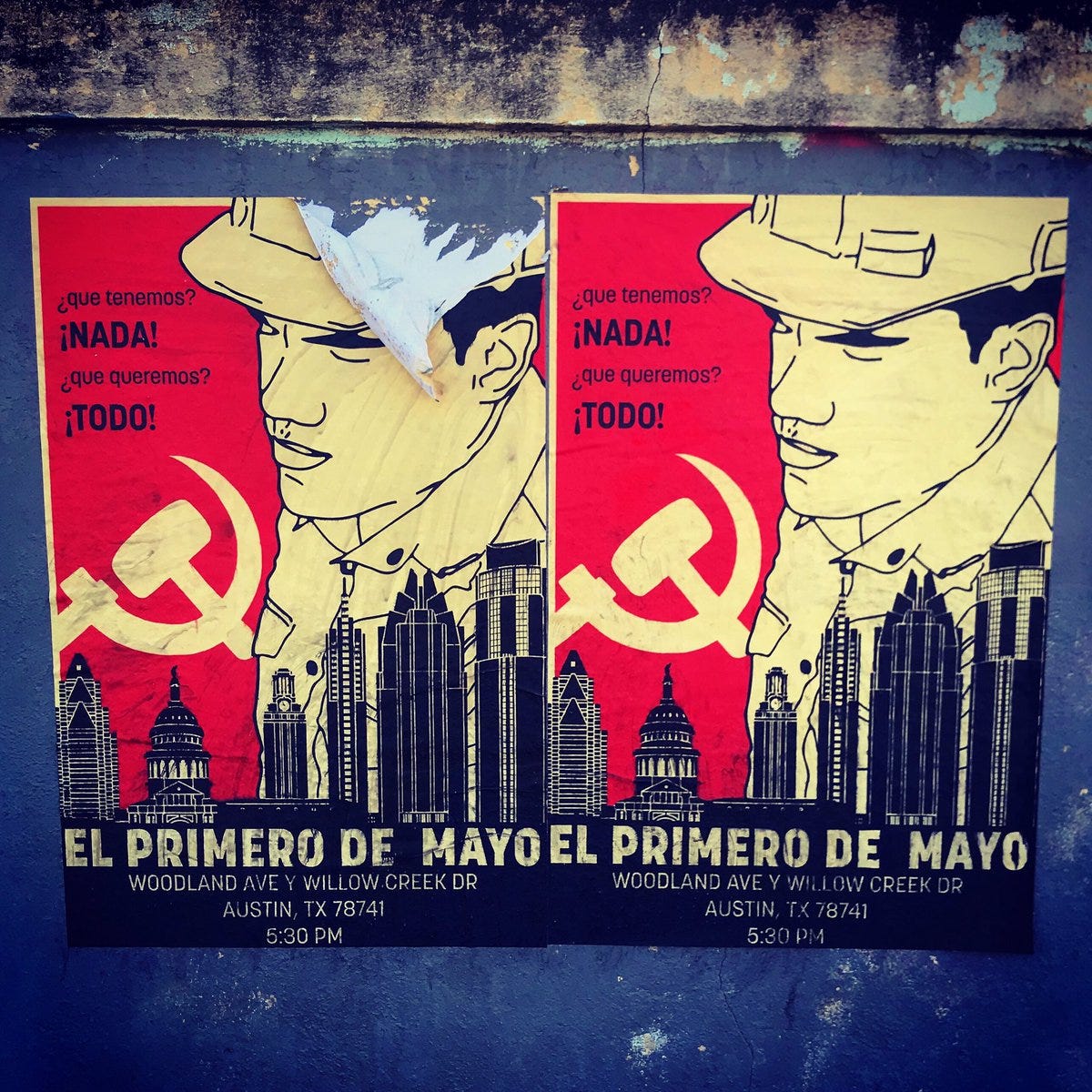

The cardinals aren’t the only reds who are showing up in force this spring. Earlier this week City Hall was tagged with revolutionary graffiti. We got a fair bit around here as well: calls to the uprising, declarations that capitalism is the real virus, portents that May Day is coming.

The news reports express a general bafflement downtown as to what this could be. Maoist revolution was not one of the transactional risk factors they covered in the real estate licensing exam. (Neither was pandemic.)

I have been seeing the signs around here for the past few years, around the same period as the cardinals have taken over the exterior of our home. The street art is there in the morning when I am out and about walking dogs and exercising, signs left by more nocturnal neighbors, not far from the tracks the coyotes leave from their pre-dawn prowls. Some of it is quite beautiful, poster art spackled to the walls of old industrial buildings, illustrated with keys that curious viewers can take to find their own way in to a different way of understanding the society in which we live.

I came upon the above poster last summer two short blocks from our house, the day after I read an article about Sendero Luminoso. This wasn’t long after I had sat down for lunch at my favorite vegetarian Tex-Mex joint and witnessed a mob with those same red bandannas over their faces and megaphones in their hands, protesting the redevelopment of the old llanteria across the street. Gentrification is colonization, I thought, and is producing more radical futures than the Chamber of Commerce can imagine. And the dystopian novelist in me always wonders at what point the megaphones and placards get replaced with Kalashnikovs.

The first or second summer we lived here, in a little rent house next to our lot, the old neon plant across the street had been repurposed as the staging area for #Occupy. They were busy—you could hear them at night, planning their next action, producing the tools of their nonviolent fight for change. Sitting out there on our porch after dinner listening to the herons and frogs and the trucks on the bridge and the change agents conspiring and taking hammer to anvil, you couldn’t help but wonder what something like that could morph into under the right conditions. I ended up writing a novel, Tropic of Kansas, that took that premise and ran with it.

One can imagine what the response would be if the people who put up those posters showed up in our state capitol with AK-47s and red bandannas, exercising their Second Amendment rights. But the posters were just posters, and another May Day came and went Friday without any sounds of insurrection or counterinsurgency at the edge of town.

The problem with utopian political theories is that they are theories—designs invented by humans and imposed on the world, premised on the notion that we can change our nature. I’ve read more than my share, including volumes of ponderous considerations of the paradox that the theories of proletarian uprising hatched in the peak of the industrial revolution ended up mainly being deployed in service of peasant rebellions. People seeking liberation, like wild birds learning to survive in our habitat, work with available materials.

This decade we have lived in the urban woods, I have come to believe that the real root of most of the injustices in human society lies in the way we have made the Earth our slave, and had to enslave each other to make that system work. Maybe that system is even more against our true nature than the fantasy that wecould create a society in which all people will be good. And maybe if we each worked a little harder to meet our non-human neighbors half way, the way they adapt to us, we might be able to incubate a real future we would all want to live in.

If you’re looking for ideas about different ways to get outside, you might dig this Katherine Rundell piece at the London Review of Books, “Night Climbing,” on urban exploration. It’s part of the LRB’s wonderful “Diverted Traffic” curated series of pandemic-ready diversions from their archive.

Thanks for reading, and have a safe week.