The Anternet connection

I put some trailcams out the week before last, the first time I’ve done that in a couple of months. I found a dead armadillo in the yard one morning at the beginning of June, so I set it outside the fence right by the camera that later caught the scrawny coyote pictured above on the morning of my birthday. Armadillos are kind of heavy, at least in the spade of a work shovel, and when I dropped it too hard it rolled right down the hill, pure slapstick fail, into a ravine at the corner of our lot that is also the graveyard of large quantities of trash from the 1960s and 70s. So I strapped my other camera to one of the scrubby trees that grows up out of the old tires and TVs and car parts, and returned yesterday to see who had shown up there in the woods behind the door factory.

And just like they say, the first scavenger to appear was a solitary turkey vulture, shoving its head in there with gusto.

The more social black vultures came next, followed by a pair of crested caracaras. Sometimes I see a single caracara on a telephone pole or cell phone tower with a committee of black vultures, and they always look a little ridiculous in that company, acting as if they fit in. But I guess they have figured out that hanging with vultures is an easier way to get the food someone else already killed. In this case, the caracara spent a few minutes strutting around cockily and checking the scene out. Then finally one of them went in and contested the dominant vulture for control of the carcass. On the video, it looks like the caracara wins, but when you look at the frame-by-frame, you can see the vulture gets it on its back and dominates it, no matter how cool it tries to look. In the subsequent minutes, the caracaras get crowded out by the vultures, and split.

Here’s the best minute of video (not too graphic, but maybe not for the squeamish). For the full experience, turn on the sound so you can hear the wing beats and weird vocalizations:

*According to Wikipedia, a group of vultures is properly called a kettle when in flight, a committee when resting in a tree or on the ground, and a wake when feeding. The entry further advises that vultures are also sometimes referred to in English as Geier, from the German—apparently popular with poets, who perhaps associated these death birds with the Teutonic aesthetic.

The algorithms of ants

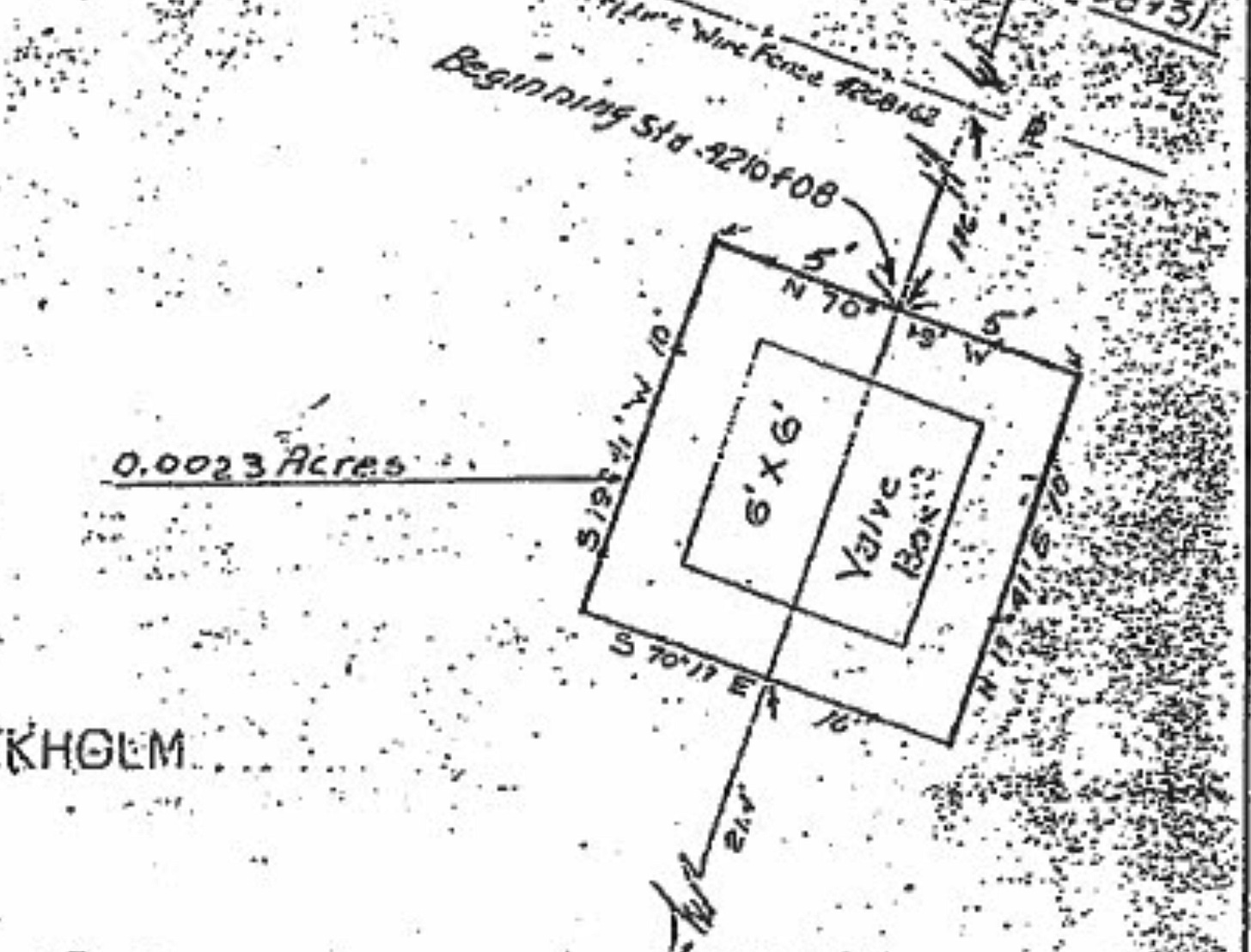

Before we got here, the whole lot was a dump site. And right in the middle was a big portal into the Earth. It was a valve box for the Chevron crews to access the petroleum transmission pipeline that bisected the lot, but it looked like one of those entries to the underground base those marooned passengers would find on Lost—a door in the ground with a wheel like a ship’s hatch and a padlock that tempted you to cut it, crank it open, and see what alternate reality you might escape to.

Nestled up against the box was a huge colony of harvester ants. Always easy to spot because of the way they clear the vegetation around the entry to their nest, and often take advantage of human structures to make their nest stronger, in this case using the steel wall of one side of the box. Out from their sterilized ground zero radiated several trails through the Bermuda grass, sometimes intersecting with the tubular pathways of the voles, and on summer days you could watch the foragers coming and going with their loads like a busy shift of Lilliputian stevedores.

They were big ants, colored a very Texan reddish brown, and if you managed to get bitten by one you would learn how much more strong and venomous they were than the neighboring fire ants. My son, then a middle school nature nerd, was especially fascinated by them, and we spent fair chunks of our Saturdays observing their behavior, watching how quickly they would remove any little bit of vegetation that might land in their zone. Our neighbor, an entomologist who also admired the ants, said the nest probably went sixteen feet down, and could have numbered more than a hundred-thousand inhabitants. A myrmecological metropolis.

When Chevron finally sent their crew out to remove the pipeline, which had been shut down fifteen years earlier, they were stymied by the ants around the valve box. When they hit them with the backhoe, the ants managed to shut down the entire operation with their defensive response. So the corporation classified them as a biohazard, and worked on alternate war plans. One afternoon I stopped by at lunch and found the crew boss, a young woman geologist overseeing a crew of roughnecks, supine in the bed of the company pickup, flushed and sweaty, attended by the others. They said she had been attacked by the ants, and they were awaiting a medical response. Only later did they tell me it was a drill, one only she and the foreman were in on.

[Still from THEM (Warner Bros., 1954)]

They ended up just burying the ants in enough dirt that they could work around them. And when the architects got their crew out to build our little house in the trench left by the pipeline excavation, they did the same thing. We figured the ants had been exterminated, which was a bummer, though there were many colonies nearby. But then the spring after we moved in, they reappeared, right at the top of our entry stairs. The same spot where the valve box had been, using the concrete structure instead of the steel walls. An inconvenient location for the humans, as we had to navigate around them every time we came or went, but their resilience made them all the more charismatic and weirdly welcome. No matter what “the Orkin Man” says.

Harvester ants are the main food source of the Texas horned lizard, and the efforts to exterminate the ants from homes and ranches is the main cause in the decline of that signature species. My dad tells a story about the Boy Scout Jamboree he attended as a small town Iowa boy in the 1940s, and how all the Texas boys on the train had their own horny toads they carried with them like the familiars of some Lone Star Slytherin. I have been here more than twenty years now, and have never seen one in the wild, though we have plenty of their lookalike Texas spiny lizards.

Underneath our welcome colony was the utility closet for our home, in which was installed our main Internet router. And a couple of years after we moved in, I read about an interdisciplinary study which discovered that the method by which the harvester ants regulate the coming and going of their foragers is almost algorithmically identical to TCP/IP, the main communications protocol underlying the Internet. Harvester ant colonies send out foragers based on the rate at which others are returning with food, the same way outbound packet speeds are set based on the speed of inbound data.

So as I read about the spontaneous emergence of a temporary autonomous zone in Seattle, like some real-world manifestation of the utopian islands in my dystopian novels, I wonder if maybe we might someday be able govern ourselves on a truly distributed basis, without leaders or hierarchical power pyramids, as the ants who discovered that algorithm millions of years before us do. It’s the way our pre-agricultural ancestors are thought to have lived, in collectively governed bands of 50 to 150 people. Maybe better information systems can help us find our way back to our true nature, without presidents, CEOs or bosses.

Our front door colony finally disappeared a few years ago—not from extermination, but from a yard so feral with vegetation that they couldn’t keep the plants at bay. Or so I thought, but in the past week, harvester ants have reappeared on our main trail. It might be a new colony, but it is nice to see them. If we pay more attention to what they have to teach, who knows what we might learn.

[Pic: animal burrow found Saturday in the ravine of trash, made from an old tire and a 1970s color television]

Partially identified flying objects

During quarantine I have been having a weekly Zoom chat with some of my nerdy sf writer friends in which we check in and discuss an assigned movie of the week. This week’s viewing was The Vast of Night, an indie production that got picked up by Amazon, the story of a 1950s border town DJ and switchboard operator who have an encounter with alien spacecraft. I have been working on a new fiction project that may include some period U.F.O. material, and the movie was a nice pop culture counterbalance to the Carl Jung book on Flying Saucers that I have finally gotten around to reading. The movie was shot in some small towns north of Waco, all after dark, and really captured that feeling when summer nights bring nature right up to the edge of the human habitat.

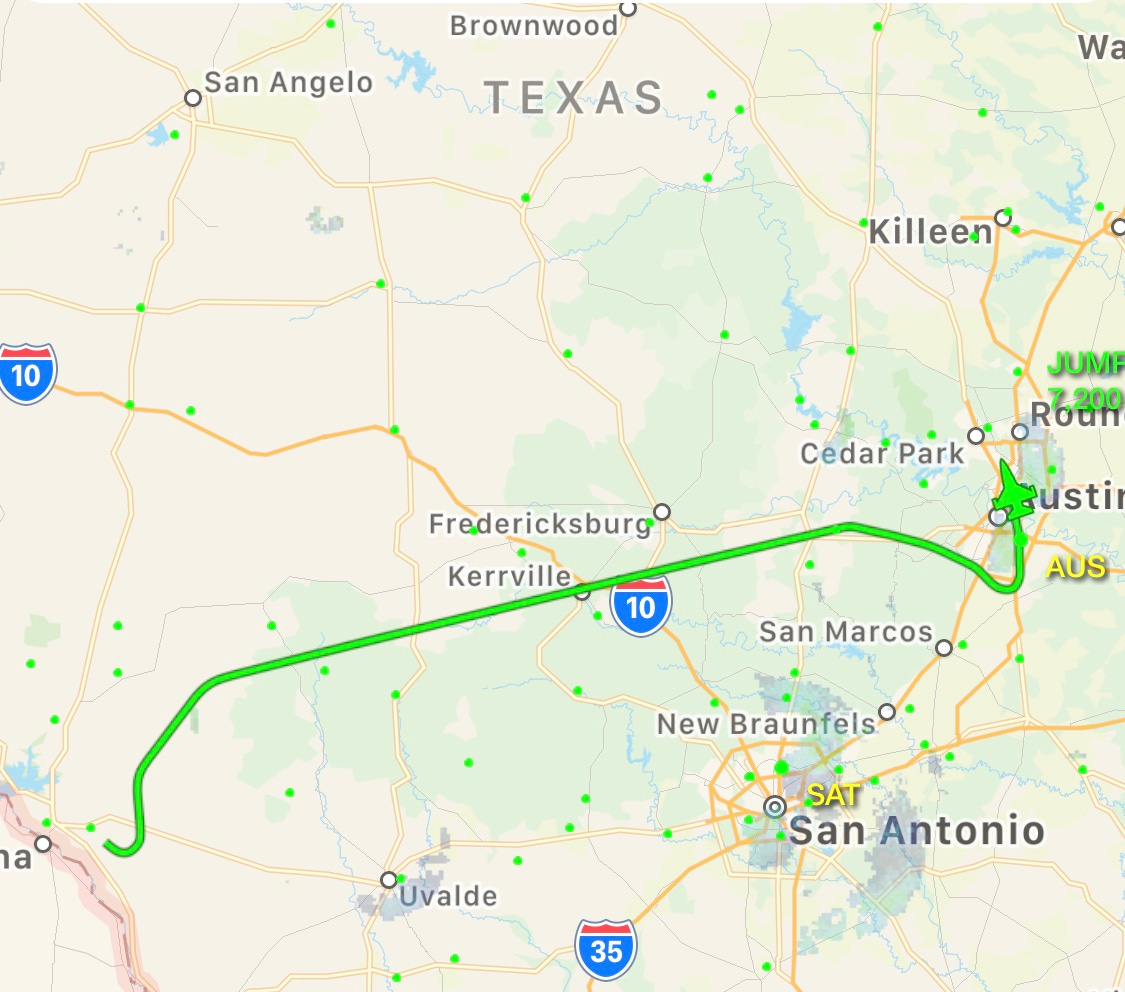

The ending was dark and enigmatic, and when I walked outside into the night air after I closed my laptop, I heard the roar of a fighter jet close by, flying low. I looked up and just caught it buzzing the woods next to us, then heading off to the north at a high speed, visible only as a red light rapidly disappearing into the void.

The liminal spaces of Texas are hospitable to weird military activity, especially on quiet nights. A few years ago we visited the Marfa Lights viewing area on Highway 90 west of Alpine with friends visiting from New York, and when I stepped out to take a closer look, through the darkness I saw a seemingly endless train charging eastwards across the road, loud yet stealthy, loaded with big tanks on flatcars. Operations like that are usually cloaked in mystery to the casual civilian witness, providing great fodder for those like me prone to conjuring Area 51 narratives. Once I looked up in the afternoon sky over our house and saw a giant jet escorted by five fighters, only one of which showed up on the flight radar, with a call sign registered to NASA. And as I watched its trajectory on the computer, it went over the Gulf and suddenly disappeared.

It used to be that the commercial flight tracker apps didn’t display any military activity, but now they do. No flight plans or call signs, but I was able to deduce this week’s visitor was a training mission out of Laughlin AFB down on the border. If only the trajectories of the migratory birds that travel through this corridor were as easy to track.

More Black Nature Writing

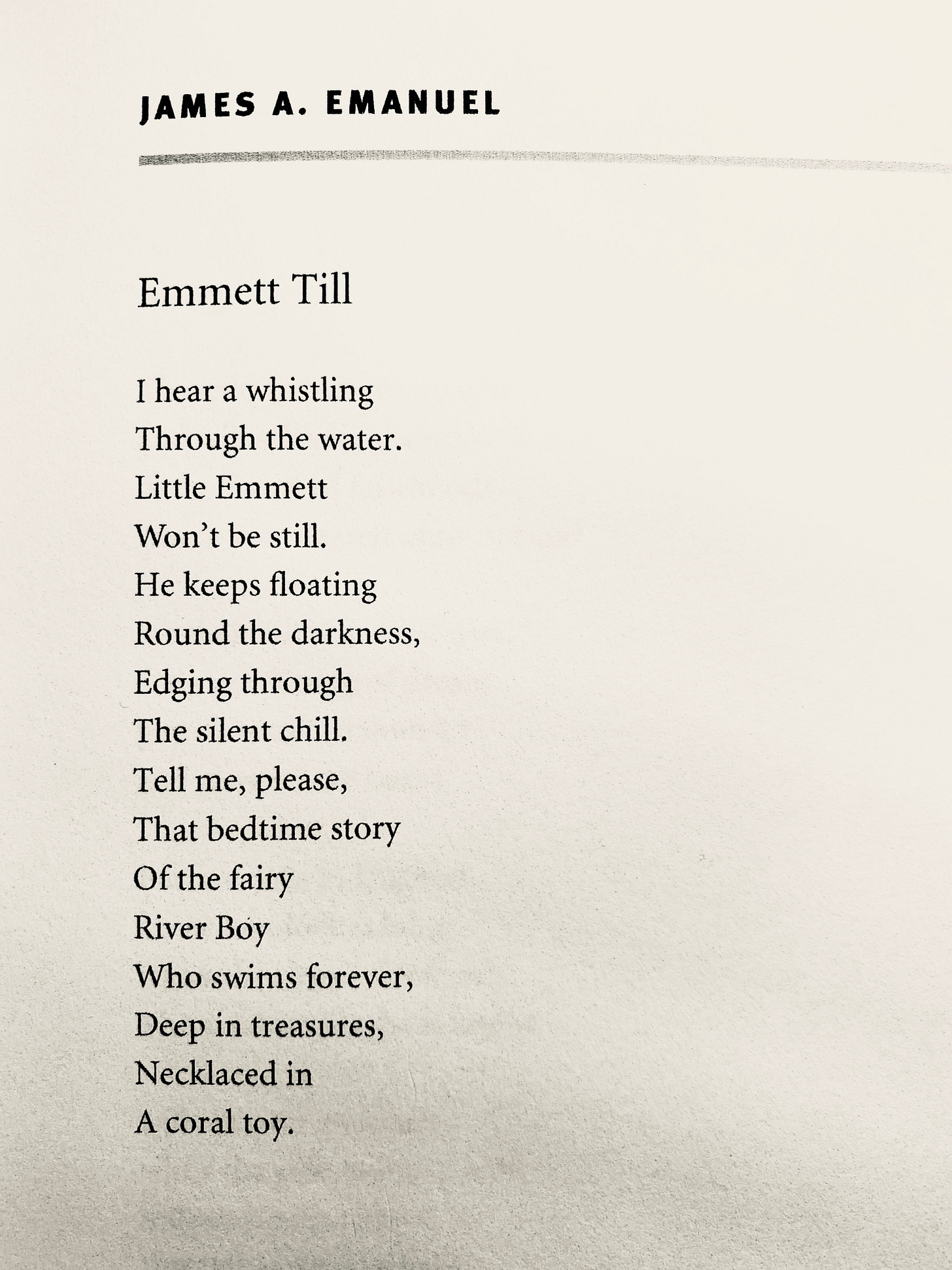

Thanks to all of you who shared last week’s newsletter focused on nature writing by black authors, and helped that be the most widely read issue of Field Notes thus far. I hope to continue to feature such voices, in the hopes that you will check them out. Monday’s mail brought me a copy of Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry, edited by Camille Dungy. Here’s one poem that stuck with me, a remembrance of Emmett Till in dark romantic verse, by James A. Emanuel (1921-2013).

Emanuel’s poem resonated with the Evelyn White essay I shared last week, “Black Women and the Wilderness,” which discussed how her childhood exposure to the same story impacted her relationship with nature and the outdoors. If you didn’t read that piece yet, please click here and check it out today if you can—it’s a quick read, and an powerful one.

Extras

For those who made it to the end, a couple of bonus videos. First, that scrawny coyote stopping to check out the camera at 3:30 am Wednesday morning:

And a rather vocal red-shoulder hawk atop a power line Monday afternoon below the tollway bridge:

Have a safe week.

Further reading:

“Stanford researchers discover the ‘anternet,’” Stanford Report, August 24, 2012.

Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry, edited by Camille T. Dungy (2009).

“Black Women and the Wilderness,” by Evelyn White, from Literature and the Environment: A Reader on Nature and Culture, edited by Lorraine Anderson et al. (1999), also collected in The Norton Book of Nature Writing (2002). Full text online here.