The 2% Cash Back Starlings

Saturday morning at daybreak I headed out with the dogs for a deserted traffic island near our house. It’s at the spot where several municipal streets that lead to downtown from the eastern edge of the city converge, and then merge into the on and off-ramps of the old highway that follows the course of Walnut Creek to the north and crosses the river for the Bastrop highway to the south. In a car or on foot, it’s a labyrinth of loco loops to nowhere designed by 1960s traffic engineers, who no doubt thought it was a tidy little network node of ambulatory American utility. In the last couple of years leading up to the lockdown, the cars would line up for hours every night on those onramps, which were also designed for 1960s traffic.

They’re turning the old highway into a high-speed tollway now, and one of the bigger traffic islands into a major bus transit station, construction that has several of the roads in the not-quite cloverleaf closed, creating new dirt trails for those who like to walk and run where they are not supposed to. Every morning the big earth movers are out terraforming the transportation future that was encoded pre-pandemic, and every night the deer and the wild canids come out of the nearby woods behind the industrial park and roam the emptied streets, leaving intrepid tracks across the freshly graded earth.

Because of the construction, the buried lines are all marked, and you can see what a crowded data highway it is as well, with the orange cones of AT&T, the manholes of MCI and Level 3, and the spray-painted cryptograms of the also-rans. I’ve been re-reading Ingrid Burrington’s outstanding Networks of New York, which includes an incredible decoder’s guide to the sigils of 21st century network infrastructure, and while the codes she compiles don’t fully translate to Texas, they give you a good idea of what you are looking at.

The traffic island we traversed was extra green in the morning sun, juiced with a a few days of much-needed rain followed by a few days of cooler temperatures and sunny skies. Thursday morning it was in the mid-50s when I walked out to my office before sunup, an astonishingly refreshing feeling after six weeks of triple digit heat. Perfect conditions for the grasses to start their fall growth. The native Indian grasses on our roof immediately started dropping their seeds, and the wild bromes that crowd out the good grasses could already be seen popping up on the floor of the woods before the rain had even stopped.

In our backyard, the spiderwort was emerging early from the dismal soil where people used to dump trash, soil you are afraid to stir for fear of what you might dig up. Maybe it likes the crumbling old concrete mixed into the dirt, or maybe it just likes the shade, and the absence of competition.

Across from the traffic island is a big billboard above the truck repair shop, rising up from that right of way full of fiber-optic cable and above-ground power and telephone lines. The signs on the billboard change every few months. Earlier this summer, the east side advertised a 2% cash back credit union debit card. Now for the last few months it has featured the determined face and red tie of Alfonso Campos, Esq., whose billboard handle is El Abogado Fregón, which roughly translates as “the pain-in-the-ass lawyer,” fregón being a word that can variously mean things like annoying, fastidious, or cleaning scrubber, depending on the context. For a personal injury lawyer advocating for accident victims and taking on insurance companies, it’s kind of an awesome drive-by line.

Behind el Abogado Frégon is where the only colony of European starlings I have seen in this neighborhood live. A bird that is an even bigger pain in the ass than the most annoying lawyer.

I have seen the starlings on other billboards. They hang out on top of them, or nearby, but I’m pretty sure they nest inside, because you will often seem them emerging and returning through the top corners, where the pre-printed sheet pasted over the permanent structure hangs loose. It makes sense—European starlings are cavity-dwelling birds, famous for aggressively displacing the nests of native woodpeckers, bluebirds and owls, often killing their young in the process, pecking those needle-like yellow beaks through baby bird skulls because they are too lazy to build their own nests. The rare bird so invasive and obnoxious it even rates an article on the Audubon site explaining why it’s okay to hate and even exterminate them.

It’s a great adaptation for them to live in the metal corners behind the faces of plaintiffs’ lawyers and low-end orthodontists, and perhaps a sign of the ecological health of the zone where we live, which is rich with woodpeckers and big owls in the woods that stand just a couple hundred yards from the billboard. I never see the starlings in the woods where the native birds thrive. Maybe the hawks keep them away. The starlings are mostly to be found on the power lines that line the streets, the males flashing their multicolored chests like Reeperbahn pimps.

A green guerrilla friend of mine once saw a group of them hanging out on our street, and told me I should buy a BB-gun and start taking them down. But I never see them in our wild yard. I like the idea that maybe the the city still has enough wild in it that it can achieve and maintain balance over time. That maybe even the most hated avian species in America can find a niche not already occupied by others. It makes you wonder whether maybe we, the most dangerous invasive species of all on this continent, can too.

Coralillo slither and ladybug love

This week’s algorithmic regenerator served up two wonderful video memories, both from the same day four years ago this weekend.

The first is one of the biggest coral snakes I have seen, big enough to have wrapped itself about a decent-sized hackberry in our yard, where I found it one morning after returning from a walk in the woods. The coral snakes love our green roof, and when you find them on the patio in the evening or morning, hunting for lizards, you don’t need to remember the mnemonic.

That afternoon, I happened upon my first sighting of ladybug procreation in progress on our green roof, right by our front steps. If only Cole Porter could have reported on how Coccinellidae do it.

Have a frisky week.

Further reading

“Birdist Rule #72—It’s Okay to Hate Some Birds,” by Nicholas Lund, Audubon, March 2016

Networks of New York: An Illustrated Field Guide to Urban Internet Infrastructure, by Ingrid Burrington (2016)

“Red on yellow, kill a fellow”—Wikipedia on the Texas coral snake, Micrurus tener

Bonus feature: letters to Field Notes

In the mind of its author, this newsletter is a little bit like a letter to friends, and sometimes they write back. This week I got a nice note from the librarian, antiquarian bookseller and digital newspaper editor James Foster about his summer of pandemic hikes, and thought I would share it (with his permission). It’s especially of interest to folks in the Austin area looking for new urban trails to explore.

Pathfinding through the Pandemic

by James Foster

It all started off innocently enough. Kim and I had started hiking around Austin in the fall of 2019 for shared exercise and with a vague goal of day-hiking the South Rim of Chisos Basin in Big Bend in June 2020. We even committed to a Chisos Basin cottage for that time, rented back in December 2019. In preparation we were going on short weekend outings at the common local spots: Bull Creek, Violet Crown, Barton Springs Greenbelt, the local State Parks, Balcones Canyonlands Wildlife Refuge out south of Bertram. Then came March 2020 and everything changed.

Kim is a teacher at a small private school and her classes went immediately to an all online curriculum which she had to develop for K-1 grades on the fly from March through the end of May. Our schedules flew out the window as we were all adapting to the new pandemic landscape. We quickly lost our hiking chops just as we were getting into shape.

By late May it was clear we’d not be trekking to the South Rim of the Chisos Basin, but despite our cottage reservations being canceled, we still took to the road for a couple of days in mid-June to explore Big Bend National Park and Davis Mountains State Park. We enjoyed some great hikes in both parks and came home re-committed to walking off the COVID blues.

For the past few months, we walk daily and take to the trails each weekend. We remain modest in our expectations, but use the time to learn about the geology, flora, fauna, and natural history of different spaces in central Texas. While there are no shortage of trails in Austin, we also want to keep away from the crowds and out of the heat. We go early and we try to find trails less traveled. To that end, Google Maps has been unexpectedly helpful.

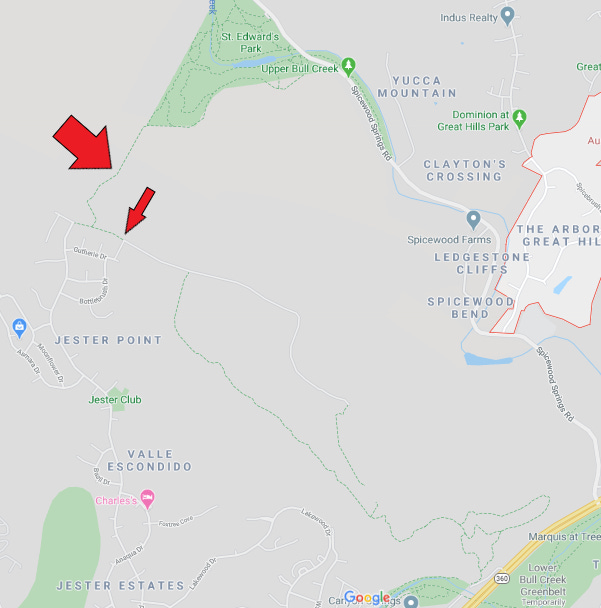

For example, one afternoon, after a modest exploration of the heavily trafficked St. Edwards Park in Northwest Austin, I checked Google Maps to review how the creek runs through that park and where certain creek crossings might lead. To my surprise, when zoomed far enough out, I spied what appeared to be a trail from the very top of Jester Estates back into St. Edwards Park. Upon more exploration there appeared to be a small network of trails from up on that hill leading into the park and down to Bull Creek.

In July, we set off early to arrive at the apparent trail head around 6am. We drove into Jester Estates and up the steep hill passing all the big houses. Juxtaposed against the mansions and backyard pools, at the very end of Jester Boulevard, we found the trail entrance, the asphalted development simply running out of space and opening to the juniper dominated landscape.

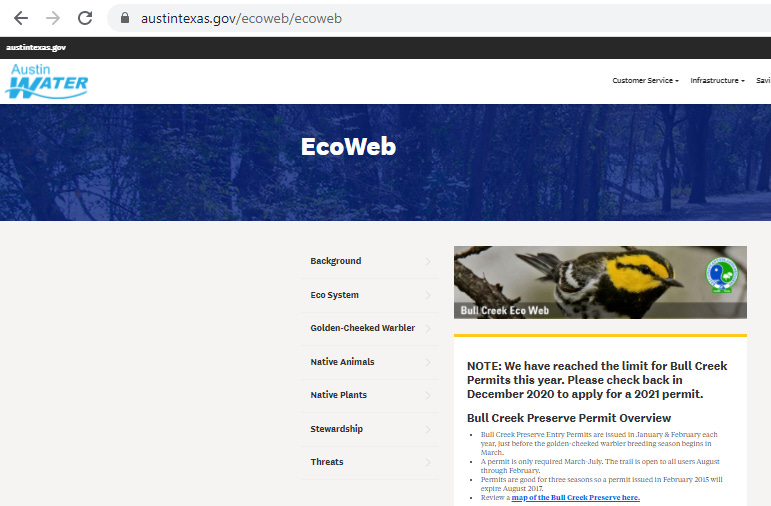

There were signs indicating you needed a permit to enter from March until August since this area was part of a nature preserve and it was Golden-Cheeked Warbler breeding season. We backed off and headed elsewhere for the morning, but were committed to returning once the area opened up.

Turns out the area under consideration is part of the Balcones Canyonlands Preserve (not to be confused with the Balcones Canyonlands National Wildlife Refuge), a system of 100+ tracts of public and private lands managed through multi-agency cooperation and one of the largest urban preserves in the nation. The preserve encompasses multiple ecosystems of the Edwards Plateau and is a model for balancing land development and conservation in urban areas. A scan of City of Austin EcoWeb website devoted to this part of the preserve uncovered some background information of the flora/fauna of the area and at least a rough map of the trails.

Early on Saturday, August 1, we were the first to park at the trail head and off we wandered. The trail initiates in the preserve and is well-marked, with some fenced boundaries that warn folks to stay in line on the trail.

Soon the trail exits the preserve proper and you are in the backside upslope portion of St. Edwards Park. Once in the park, you start descending the ‘balconies’ of limestone towards the river. The trails can be rocky, gnarly, and, in some areas, lead unexpectedly to the edge of sheer cliff faces dropping to the water below. We thought we were clever going laterally on one of the trail spurs and found ourselves precariously peering 100+ feet down to Bull Creek.

After carefully moving through and out of imminent disaster, we hoofed through the swarm of horse flies back up the hill. A modest hike, but it’s not always about how far or fast you go, but more that we explored new spaces, discovered via Google Maps. We are logging 20+ miles of hiking a week. We even talk about hiking gear and a return attempt at the South Rim. In this time of isolation, we are committed to getting to know the wilds in and around Austin and the rest of Texas just a little bit better.

I loved, “Reeperbahn pimps”.

I wondered if Dr. Chuck Sexton was involved in sanctuary for the Golden-Cheeked Warblers, which is his specialty.

Great post. Thanks.