Teen birds and Hackensack Voyageurs

Monday morning baby and I walked down to the river and came upon this juvenile green heron chilling by a little backwater where they used to dredge gravel. I think it was a green heron—juveniles are always challenging to identify. Unless, like the first spring male summer tanager I wrote about here a few weeks ago, they are so spectacularly plumed as to rate an illustrated footnote in the guides.

The remarkable thing about most juveniles, birds or mammals, is how unwary of humans they are. This heron let me walk up to it with a squawking baby on a backpack and two leashed hounds radiating predatory energy, close enough that I could get several detailed shots with no more than my phone. At one point it wound up as if ready to fly, but then relaxed again. It was still there, in the same spot, when we walked back that way half an hour later.

Here’s another one, from a couple of seasons ago, clearly a heron but even harder to say which species. My guess is it’s a yellow-crowned night heron

Teenage great blues are easier to spot, usually looking like some high school freshman who just had their growth spurt and can’t eat enough to keep up.

The juvenile songbirds usually exaggerate their species’ distinguishing features, like this young male cardinal with a crested ‘do that reminds me of the Echo and the Bunnymen-ready haircut I had in the mid-80s.

Because our green roof and wild yard provide so much cover, many birds nest right by our house, and as a consequence the fledglings can sometimes be found learning to fly in the concrete patio. I found this young sparrow a while back chilling on the handle of our front door, seeming to fly before it could even keep its eyes open. You can see from the picture—again taken on a phone—how close it let me get.

Songbirds of all ages love to bathe in our chlorine-free pool, which is surrounded by trees and green roof forms, and has a negative edge that provides a perfect shallow platform and the additional enticement of the sound of running water. And once in a while, they throw a teen bird pool party.

Juvenile birds provide a nice reminder of the open-mindedness of youth in any species, even as the fresh songs of spring shift into the struggles of a long hot summer.

Sunday morning diving down

Last Sunday morning baby and I walked on the streets instead of the woods. On the weekends, especially early Sunday, when the human hive is mostly at rest, you can always find plenty of wildlife roaming more visibly in our domain. My son and I once saw a coyote downtown on such a Sunday morning walk, as we took a shortcut along the train tracks headed to our favorite diner. It was in our path, crossing the rails from a thin patch of woods behind the YMCA, not far from an old gumball machine someone had dumped down there in the ballast, and it gave us a good stare before loping on its way.

The city re-paved and restriped our street recently, providing some of our neighbors with a better reason to break out the roller skates as balletic quarantainment. It also provides a slightly improved palette to spot the urban wildlife action. And as we walked the long block on our return, we saw this little raptor enjoying its fresh kill in the middle of the road I have seen this bird before, I think, in this general vicinity, but never for long enough to make a good i.d. It’s usually before the light is really out, on those days when I walk the dogs before sunrise, and you can just catch that striking silhouette diving from the power line to surprise some rambling rodent. From those sightings I had guessed some kind of kestrel, but now I am pretty sure it’s a broad-winged hawk.

When we saw it Sunday morning it was in a shadow in the middle of the road, right by the double yellow lines, pulling tendrils of meat from a fresh carcass the way raptors do, rough surgeons of beak and claw. This was not far from the spot where a turtle that was fresh roadkill two weeks ago has been slowly disintegrating under the steady grind of June heat and overriding truck tires, relic of an adventurous egg-laying mission gone bad. As we approached, the hawk finally took off, carrying its prey into one of the trees in our neighbors’ front yard. You could see from the feathers that the prey was another bird, probably a mockingbird judging from the coloration. And when I zoomed in the above phone photo, those dangling talons told the story more clearly.

Back Water

Two years ago I spent a day exploring the New Jersey Meadowlands with my son and now-daughter-in-law, when they were still living in New York. It was something I had wanted to do for years, having seen that ultimate American edgeland through innumerable plane and train windows and been captivated by its insane mix of the heaviest industry and the wildest eastern wetland. I read about it, and talked to my friend in Montclair about paddling through the zone. When I finally got out there, it was on foot, in the tamed space of a state park, but it was still awesome.

Friday night I screened a movie that takes the trip I daydreamed about. Back Water is a one-hour documentary by New York-based artist Jon Cohrs about an expedition he and a group of companions took a few years ago, bravely exploring the Meadowlands by canoe. The film has been around a while and is getting a well-deserved fresh run at reaching a wider audience, thanks to pick-up from Apple TV+ and Amazon Prime. It’s a cool project, and a good film, and if you like this newsletter I bet you will dig it.

It’s a Brooklyn hipster project, outdoing the Gowanus Canal tours of a decade ago, and the banter among the urbane young expeditioners gets dangerously close to the edge of Portlandia on a few occasions. You can tell a fair number of the paddlers have not spent much time in a canoe. But things like that only help you realize the genuine courage and danger of the undertaking, and the spirit of 21st century adventure that animates the crew (which includes several talented young filmmakers, a forager cook, one terrific food writer, and a lawyer), as they evacuate camp when a flood warning comes in on the first night of their trip, paddle past abandoned malls and burning LNG plants, and face off against a daily barrage of cops and corporate security details. In humans, the unwariness of juveniles, especially those of a certain class, can get prolonged well into adulthood.

The film is full of beautiful shots, but the best scenes are when they need water, and knowing how toxic the river in which they paddle is, they pull ashore and traverse the concrete wastelands on foot to find the nearest convenience store or Home Depot. A landscape that often proves even more treacherous, as when they find their plans stymied by eight tracks of high speed rail. There’s a beautiful vignette where one of the women quietly builds a good fire from found kindling at one of their apocalyptic campsites, and you are reminded that the most important means of production each of us needs to seize on our own terms is the Promethean one, even if it’s also the one that birthed the Anthropocene hellscape through which the film travels.

Here’s the trailer, which gives a pretty good sense of the story and scene:

Watching the film on Juneteenth, I couldn’t help but wonder how different the expedition would have been, and how much braver the expeditioners would have had to be, if they weren’t all white. But even when you realize how much unacknowledged privilege is on display, Back Water does a great job of taking the viewer into America’s true wilderness. It obliterates the boundary between the city and wild nature, and helps us imagine how the ravaged ecologies of our landscape can begin to heal themselves with a little inattention.

I was tipped off to Back Water by my friend and Field Notes patron Bruce Sterling (who in turn was tipped off by Régine Debatty over at We Make Money Not Art). A science fiction writer with more neologisms to his name than anyone I know, around the time I first met him twenty-some years ago Bruce invented a term for these places the Hackensack Voyageurs and I like to explore: “involuntary parks”—places that have had some of their wild restored or preserved through the accident of industrial contamination and exclusion. The Meadowlands is probably the biggest involuntary park in America, and a visit to it reveals the history of the whole country.

Reading Black Explorers

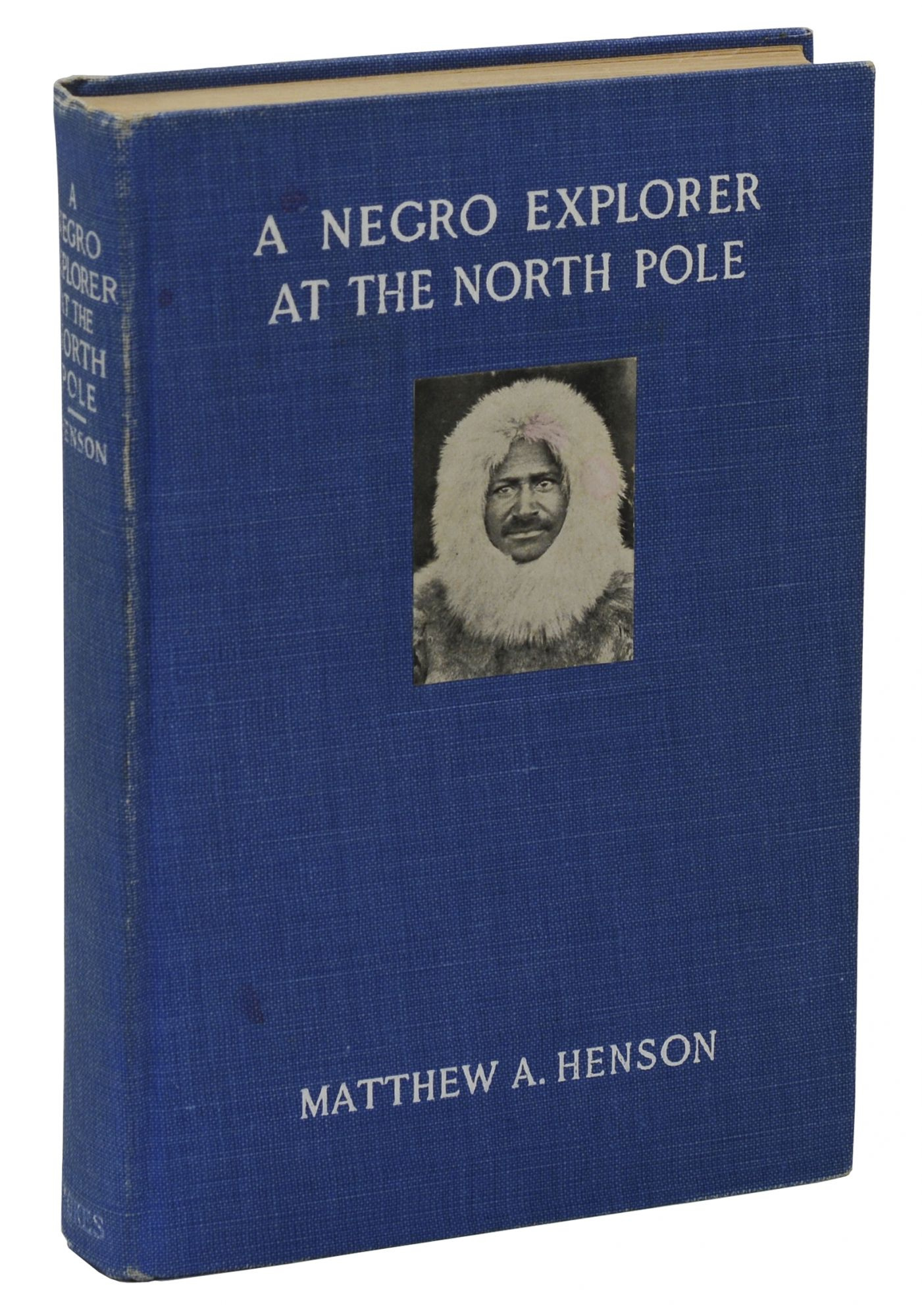

This week’s feed brought a re-share of an interesting piece from last year: over at LitHub, a reading list from writer Kim-Marie Walker of outdoors writing by black authors. Some cool stuff on there, including this book by polar explorer Matthew Henson, and I was pleased to see she also included a couple of the titles I had in my post on the topic two weeks ago.

Greetings from Texatopia

The new Texas Monthly arrived in the mail as I was writing this post: a futures-themed issue that includes a short interview my friend and fellow Austin-based SF writer Nicky Drayden did a little while back. The headline they came up with is pretty great, and the graphic is as groovy as a ‘70s Dune paperback cover:

Pick yourself up a copy on your next apocalypse-ready grocery store run, or watch my feed for a link when the full text is available online.

This week’s bonus videos: that fledgling sparrow slowly blinking like an alien from another dimension:

And best of all, a trio of juvenile armadillos at our back gate, who look just like the adults but smaller, and will visit you later in your dreams.

Have a great week.

Love this line, "It obliterates the boundary between the city and wild nature, and helps us imagine how the ravaged ecologies of our landscape can begin to heal themselves with a little inattention." Writing on point as always.