Tastes like chicken

We had two first-time encounters this week, mediated by trailcam, in footage I pulled yesterday: a bunny and a bobcat, sneaking around in the unfenced back quarter of our yard, in the urban woods behind the door factory.

The only rabbit I have ever seen in these woods was down in the tall water grass maze of the wetland behind the dairy plant, and then I only saw it for a second before it disappeared into the foliage. I always figured the coyotes and foxes kept them low in number and mostly hidden. This one looked pretty big, and pretty out in the open—alert on the video as it cocks its ears and looks around into the night. It’s possible there’s a new den back in there—there are certainly plenty of good spots for it.

I’ve never seen a bobcat in town. A few have been seen by my friend who runs the Circle Acres preserve across the river, but not on this side. I’ve seen bobcats in wild country, but never as big as the bruiser I saw lumbering through this frame, with muscular movement that made me wonder if it was a cougar at first. It came through 24 hours after the rabbit, one of its preferred meals, so maybe it was that scent that drew it to this spot.

The full 10-second video is below, including a long pause as the cat stops to vogue. Note the striping along the forelegs, the subtle cocks of the ear (the acoustic capabilities of which are aided by the hair tufts), and the stubby little tail that moves like some alien antenna. That “bobbed” tail is how Lynx rufus earned its common name. If you turn on the sound, you may appreciate how silent its steps are, a stealthy contrast with the leaf-crunching coyotes.

An amazing animal, and a wonder to see slinking through one’s urban backyard. When I first got the footage off the chip, I wondered if it might have been the creature who left the severed back half of a field mouse in the middle of our driveway that morning, but then I concluded it must have been a hawk or a domestic cat. Whoever the culprit, it was a suitable way to start Halloween.

Babies gone wild

During the day between rabbit and bobcat’s nighttime visitations last weekend, my daughter and I went for a long hike along (and in) the urban river. She’s around a year-and-a-half now, fully evolved to bipedalism, and ready to explore. Pretty fearless, as we saw at the beach over the summer when she would charge into the surf. When I let her down from the baby backpack, she was off and on the move almost faster than I could keep up with. And in that hour she saw probably more wildlife than I saw in most of my childhood, if you don’t count animals in zoos.

We came upon a deer foraging on the beach, in a spot where we could see it but it did not see us. We heard the crazy pterodactyl cry of the great blue heron as it slowly alighted in a cottonwood at the edge of the forest. We watched a pair of kingfishers dance over the wide shoals below the bridge. And as we walked in the shallows, an unlikely interspecies pair moved downriver apace with us—a white heron and a blue heron, fishing together. I wonder if they were a couple.

That we can experience this ten minutes from downtown, in the flightpath of the airport, with the sound of truck traffic nearby, reveals a lot about the possibility for cultivating wilderness in the heart of our cities. Especially when you realize that this stretch of river was, when I was her age, ravaged for the dredging of minerals from the ancient river bed.

Friday afternoon she got a different experience of the outdoors, at a neighborhood playground with her mom. After some confident runs at the kiddie slide, she unknowingly stepped right into a fire ant mound that had been built up against a little retaining wall, one of those fire ant mounds that even an adult would be unlikely to notice until it was too late.

It was horror movie stuff for her poor mother, pure swarm. Fire ants have a knack for quickly crawling up under your clothes like an invading brigade of Marines and attacking every time you move. Even after years of working around them in the yard I manage to get attacked about half the time, rarely seeing the ants until they are already biting, and then having to rip off my clothes to get them off. Bad enough to see your young child enduring that, and then you get home and the sweet angel has so many stings that she starts swelling up like that girl in Willie Wonka. When I got home, mom and baby were sitting in the ambulance with the paramedics. We knew she was probably going to be okay when, despite all her trauma, she waved bye bye to the emergency responders.

Saturday I went and found the mound and eradicated it.

There’s a certain karmic justice to the fact that our domain is dominated by an invasive venomous insect that is as aggressive a colonizer and protector of its domus as we are. Unlike most other ants, fire ants only bite to get a grip—then they deliver a real-deal sting from the abdomen, injecting an alkaloid venom that produces a sensation like a hot match against your skin. They are active year-round, and that’s why they never survive in places with real winter.

You never find them in the woods. They thrive in the areas we have modified—ecologically denuded landscapes that have been under the plow and then under the bulldozer, seeded with non-native ornamental grasses that parch out under the Texas sun. They especially love to build up against our concrete structures. They may have gotten here in the dirt used as ballast in a boat that unloaded some South American cargo in Mobile in 1930, but you can tell they thrive because we have already done the work for them of clearing out the competition.

Urban cowboy, pandemic forager

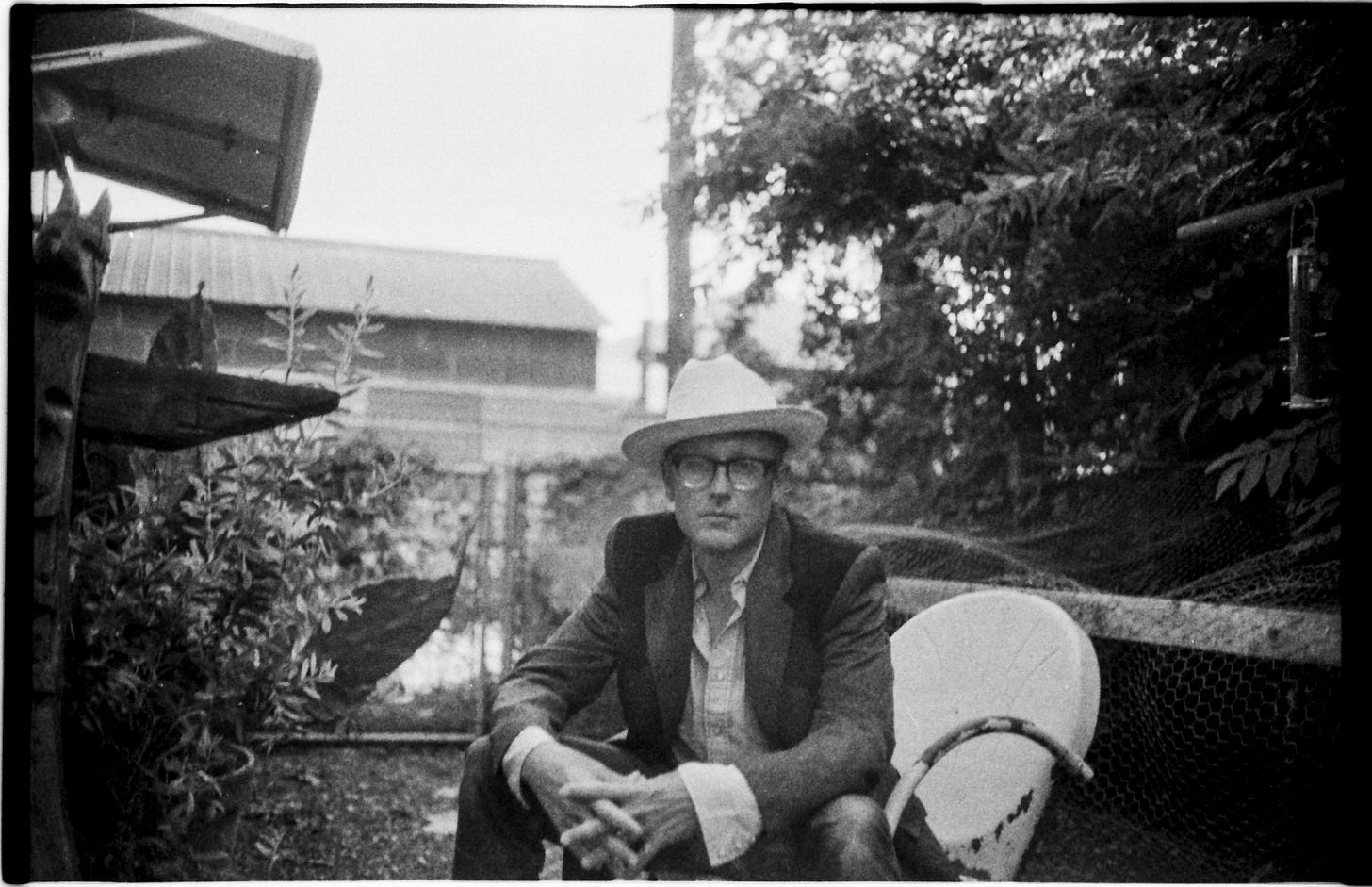

There are a handful of people I know who explore some of the same hidden trails through the green negative space of the city as me, people who I occasionally bump into on those trails. One of them is my friend Jesse Ebaugh, a musician and songwriter who can often be found far from home walking with his wily dog Scout, and who has dealt with the brutal impact of the pandemic on working musicians by taking advantage of the opportunity to become a master forager.

I was out for a trail run the other day when Jesse called, and asked where I was. It turned out he was right at the entrance of the park I was running through, with mushrooms to share. Or, more accurately, one big-ass mushroom to share. Moments later, Jesse was there in his Tacoma, smiling and holding a mushroom cutting the size of his head. And a little later, he met me back at the house for a delivery, after making a bigger delivery to some mutual friends.

Laetiporus sulphureus is often called sulphur shelf, and sometimes crab of the woods, but most of the foragers call it the chicken of the woods. Here it is as Jesse found it, in a photo he took and shared on his awesome and outdoorsy Instagram feed.

The chicken of the woods, it turns out, really does taste like chicken. We had ours in a buttery pasta that night, and then in breakfast tacos that morning.

There’s something really profound about the enjoyment of food that is of the place where you live, and harvested from the wild. This was all the more special because we knew Jesse had harvested it from an ancient oak tree we know, one of several in a hidden little wild corner of a big chunk of public land near here that, two years ago, we helped protect from a planned mountain bike course that had been staked out—an area that was also threatened by the proposed multi-family development project I wrote about in the last couple installments.

There’s evidence these trees were the site of an important Indian camp, one that was active as the area downtown was being turned into the City of Austin. Knowledge that makes one’s enjoyment of what remains of the world we displaced a bit more complicated and bittersweet, even as it helps you imagine how we could help bring more of that world back with a different approach to how we think about the urban landscape in which we live.

Cornwallis led a country dance

I was disappointed but unsurprised to read this week of the Administration’s decision to delist the gray wolf as an endangered species in the continental U.S. There hasn’t been a wild wolf seen in Texas in fifty years, after the last known survivors of the two species that once ranged across the state were exterminated in 1970. I’m skeptical of the Fish and Wildlife Surface’s sales pitchy assertion in its rulemaking that the gray wolf has fully recovered in the same way the bald eagle did, but maybe they will start showing up, even as their populations are opened up to what are euphemistically called “regulated harvests.” In Alaska, hunters are allowed to bait them with donuts, and enter the dens to kill the moms and pups.

When I was beginning work on the project that became my novel Tropic of Kansas, I became very interested in American folklore. Not the urban legends of my 1970s youth, but the older stories that mostly preceded the Civil War, the peculiarly American mythology that mixed true fact about historical personages with grandiose embellishment, in line with the old Texan saying that you should never let the truth get in the way of a good story. Stories of characters like Johnny Appleseed, Paul Bunyan, and Sally Ann Thunder Ann Whirlwind, the woman who could wrestle alligators, run faster than a wildcat, beat up all nine of her older brothers, and be so nice that the bears would let her hibernate with them and the hornets would let her wear their big nests as Sunday hats. Stories that also encode the history of the land and environment as the European settlers found and colonized it.

One of the catalysts for that deep dive into antebellum arcana was the serendipitous discovery of a wonderful volume in a now-endangered bookstore, Austin’s South Congress Books. Constance Rourke’s American Humor, originally published in 1931 and republished by New York Review Books in 2004 (with an excellent introduction by Greil Marcus), identified three key archetypes in the popular storytelling of the young nation, each of which I realized were mirrored in the three main characters I had conceived for my own effort at a folklore of the future.

The one I was least familiar with was the figure of the Yankee peddler—the lanky trader who rolls into town with a cart full of shiny trinkets, only to sell the gullible locals things they already own. But once I read Rourke’s fascinating cultural genealogy of this peculiarly American photo-capitalist trickster, I realized he shows up all over the place, under different names. His descendants include the Duke and Dauphin from Huckleberry Finn, the Wizard of Oz, the grifters of noir fiction and film, Harold Hill of The Music Man, Duke from Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury, Gordon Gekko, the traveling salesmen of 50s and 60s sitcoms, and Tony Robbins and all the other white-toothed men and women selling the secrets of success in a million infomercials.

I had a businessman character who fit the type. In my story, he was the financier of a revolution against a charismatic CEO who had become an authoritarian president. I got that idea from the many candidates I saw running for office on their business experience, and my own experience of the dictatorial character of most real-life CEOs. I never thought about the possibility that the CEO president could also be the Yankee peddler—one of those pitchmen so outrageously full of it in such a shameless and showboating all-American way that their mendacity becomes part of their unlikely charm. And then that’s exactly what happened. It was probably just a matter of time, in the age of the infomercial.

As I have watched my government rip children away from their families, terrorize many of my neighbors, and amp up our war against nature with unabashed gusto, I have always had the instinctive confidence that this will turn out like all Yankee peddler stories: eventually the yokels figure out what the peddler is really up to, and run him out of town. Their pockets are always empty by then, but they are resilient people and starting over is what they are good at. For the sake of the wolves, the bobcats, and all of our other neighbors, I hope I’m right.

Whatever happens Tuesday won’t address the deeper crisis with the aggrieved people who are the inheritors of our frontier archetypes, and the damaged ecology that produced them, as I discussed back in July in a piece exploring the connections between folklore, the land, our politics, and what Rambo has to do with all of it (“Wotan on the beach”). But for now, I’ll return to our regular and only obliquely political programming, and share this big early voting stag from Thursday night (disregard the timestamp—I forgot to reset the clock after changing the trailcam batteries):

Further reading

For more on urban bobcats, check out this WFAA piece on how the Texas red lynxes have adapted to the exurban landscape of Dallas-Fort Worth.

If you wonder who or what eats fire ants, your answer is here.

For more on Jesse Ebaugh’s real job and his band the Tender Things, check out this March profile from Billboard.

If you want to find and cook your own chicken of the woods, master forager Paul Stamets has just the infomercial you need:

Among the more interesting and less-remembered figures of American folklore is Febold Feboldson, the Nebraskan who could manipulate the weather, and who is ready for a remixed comeback in the age of climate change.

For more on my half-baked theories of American folklore and how the archetypes show up in contemporary pop culture, check out my 2017 Tor.com piece on “The Persistence of American Folklore in Fantastic Literature.”

For more on the idea of the CEO president, here’s my 2017 essay “You’re Fired — Democracy, Dystopia and the Cult of the CEO,” at NewCo Shift.

As a bonus for those who made it to the end, here’s the red-shouldered hawk I found staring at me from the Time-Warner pole Saturday evening when I stepped out for my last break before posting this:

Enjoy your extra hour, and have a civil week.