Supermoons and Superbugs

(and unlikely Easter eggs)

Tuesday night I made a point of getting out to see the full moon coming up in the eastern sky. I had seen it waxing the night before, almost full, and wanted more. I have seen pinker moons, and bigger moons, but this one was pretty epic, in part because of this weird time in our lives in which it appeared. It got me thinking about the much closer relationship our forebears had with the moon and its phases, especially the full moon and the eerie light it brings to the night. And so the pink pandemic moon put the crazy idea in my head of going for a walk in the woods with no light to guide me but its weird glow.

Maybe it was the subliminal programming I have been receiving from the loony books I have been reading our daughter:

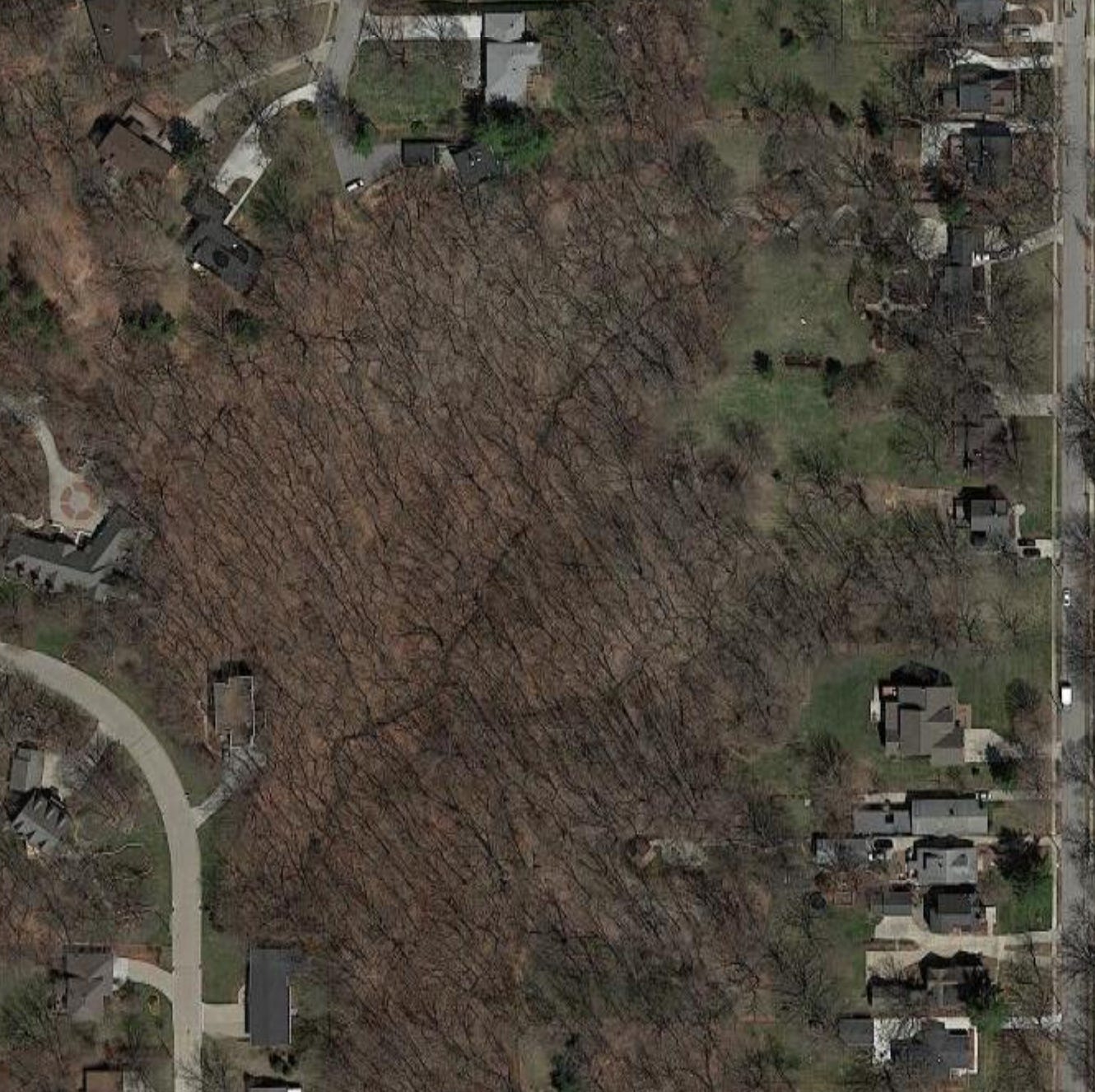

When I was a kid, we lived in a house at the edge of some suburban woods that had been set aside as a bird sanctuary when the surrounding neighborhood was developed. In the daytime, exploring those woods was one of my favorite activities—often solo, in a way few kids would ever be allowed to do today. And nothing was more terrifying to me than the idea of going out there at night. My room was on the top floor of the house, with a view into those woods, and I got pretty good at scaring myself at bedtime imagining what could be out there. Especially after my sweet mother wryly indulged my fascination with UFOs and ancient astronauts by saying how wonderful it would be if they would visit us. “Maybe they can land out there.”

I’ve had lots of experience walking in the woods at night during camping trips, occasionally with intense animal encounters. I’ve been on canoe trips where we were awakened by bears getting after our food and had to scare them off with flashlights and noise. I once had a shriek-inducing close encounter with a bat in a doorless outhouse at a remote Costa Rican campsite. I think our urban woods are scarier than the real wilderness. Maybe because I know what’s out there.

Wednesday night’s moon was super bright, but not super big, and it was really just beginning to come up when I stepped through the gate a little before 10. I kept the flashlight off from there, and for the first couple of minutes it was like walking blind. I have been walking that path weekly for a decade and know it well. But the trail is overgrown with tall spring grasses that hide all the hazards of the flotsam-strewn floodplain, even in the light of day. The snakes have been back in circulation for a few weeks now, and the night was warm and muggy. The woods are full of coyotes, and while they generally keep their distance from us, who knows what fun they might choose to have with some idiot stumbling along with his Leica in the dark.

The spring rains and warm weather have also filled the woods with the sounds of amphibian and insect life, and as you reach the river their night songs surround you in a beautiful cacophony of chirps and croaks and long slow rattles like fleshy flywheels. The rocky banks reflect the light better than the leafy woods, and it is easier to see there, but still crazy dark. When I stepped out of the woods, the moon was still behind the treeline, but Venus was setting in the western sky, in some ways more beautiful than the moon. The glow of downtown was there in the background, but it has dimmed noticeably since the pandemic cast its full shadow.

As I walked to the waterline, I could sense tiny motion all around me—flashes of light from frogs jumping back into the water, the sound of turtles dropping, the ripples on the shallow water as fish moved away. The river was like India ink. In daytime, I like to walk in the river. At night, not so much.

I walked further along the rocky bank, as the moon started to come up from behind the trees. It was easier to see in the open space covered with river rock and luminescent shells, but the visibility also made me more aware of how exposed I was. Especially when I looked over to the dark treeline twenty yards away, and wondered what might be watching.

Suddenly a big black shadow was coming straight at me—a huge bird, flying low, not ten feet off the ground. It diverted at the last minute, as I pulled my camera up. It was probably just a great blue heron, judging from the wide-winged silhouette, but my first guess was vulture. Or pterodactyl.

When I got to the bend, the moon was up, and you could see its reflection in the water. So mystical and beautiful that I got up the nerve to step out into the water and get a better shot.

I finally put the flashlight on the water, just to make sure there were no cottonmouths in my path, and caught the slow graceful wave of aquatic plants in the fresh clean flow of a side channel. The image stuck in my head like that long lingering shot at the beginning of Tarkovsky’s Solaris, when the astronaut is visiting his parent’s dacha before heading off into space, and stares into the pond. But then when the flashlight was off, I got different images in my head. A premonition of pursuit, with me as the prey, huffing as I run across the clearing, looking back over my shoulder. An instinctive fear that the rational mind can manage, but one you know is real, deeply rooted in ancestral memory.

The woods were more brightly illuminated as I walked back, the moon up there around 10 o’clock in the sky. It was still up when I woke later in the night, its bright cold stare on us through the tall windows of our bedroom. On many occasions the light of a full moon will awaken me as it arcs into morning. The full moon is the friend of the early riser, and can work like the world’s weirdest alarm. You can understand why it is associated with insomnia. And when its alien beacon compels you to go out into the night to seek it, you can understand why it is associated with insanity, and lycanthropy.

Living right at the edge of the urban woods gives you get a better appreciation of how scary they can be at night. The dangers the city works to exclude with light and razed space are right there, on the other side of the fence. Sometimes animals sneak through the fence, tempting dogs and fate. When you bring a small child into the picture, you become more cognizant of those hazards. The biggest danger in these woods is probably other people, but when you look into the dark trees those primitive feelings of predatory threats that well up inside you are telling the truth. Nature mostly works through violent competition for food and territory, no matter what utopian fantasies the sweet books we read our kids would have them believe.

But today is Easter, when the woods are also full of the new life those frog songs herald, and the utopian possibility of rebirth and peace seems real. Our yard is full of wildflowers and butterflies, even as the invasive plants try to crowd it all out. A pair of cardinals has built a nest in the cross vine that hangs over our bedroom door, insulated with plastic sheeting discarded by one of the nearby factories, and in a few months our daughter should be able to see the fledglings learning to fly as she learns to walk. Yesterday she saw her first hummingbird hovering at those same vines where they dangle down from the green roof over the living room window. In the afternoon, she reached out and ran her stubby little fingers over the fuzz of a new peach on the tree our friends gave us as one of our most treasured wedding presents.

When I got back from my walk in the night woods, I watched one of the movies that had always fascinated and sometimes scared me as a kid growing up in the 70s. The Andromeda Strain is a movie from the pandemic watchlist, about a different kind of fear—a new virus (from outer space) and the secret team of experts who combat it in their sanitized nuclear bunker. But it's also a depiction of how our entire military and scientific establishment exists at its core to maintain our dominion and protect us against competition not just from each other, but from other species. About how little we really understand the mysteries of the natural world, even when we can view it through electron microscopes and analyze it at the subatomic level. And about how our instincts to sanitize our domain rather than coexist in balance with nature are ultimately the biggest threat to our welfare.

In the morning I found myself admiring the strange egg sac that has been hanging all winter long over our front door. It was left by the yellow garden spider that built its Mordor-worthy web there last summer on the steel armature of our overhang, lustily capturing the grasshoppers and other bugs that would unwittingly leap into its trap from the nearby green roof. It’s as alien-looking a thing as any science fiction writer could imagine, like a brown paper bag that has grown veins in its skin, dangling in the dirty shredded remains of a once orderly geometric web, with dimensions that look like it could be suspending a superball, when what it really holds is the April surprise of a thousand tiny arachnids.

I wonder if they will emerge in the light of a spring day, or under the ambient glow of the moon.

Sometimes this effort to share our home with other species, to cultivate the yard as biodiverse habitat, seems crazy. The effort to rectify the imbalance of our subjugation of nature often achieves an imbalance in the other direction. Millipede infestations, coral snakes by the door, black widows behind the toilet, even a tiny snake seeming to crawl right out of the bathroom wall. In the movie version, the naive homeowner would end up the last inhabitant, at war with his domus gone wild, native gardener’s propane torch redeployed for burning down the house.

But the beauty and wonder it brings telegraphs something better that could be. A truth you can see in the health and vibrancy of the life that comes online around you in springtime, as the trees and the native plants soak up the rain and sun, and the cycle renews. My feed this spring is full of photos of friends and neighbors conducting similar experiments in their own yards. A not so clandestine network of dissidents in the war on grass, cultivating a deeper network of islands of wild inside the urban core. The hivemind is full of great snark these days ridiculing our romantic memes of wild nature suddenly rebounding as humans shelter in place. What they don’t understand is that the wild is already here, and has been for a long time, hiding in plain sight, waiting for the day when the lawnmowers never return.

The news from Iowa

Speaking of my mother, I am delighted to see she has revived her own nature blog, about life in the 200-acre oak savannah in Southern Iowa she and my dad have been restoring for the last three decades. She is a better naturalist than me, with a deep and intuitive understanding of what’s going on in the land. I attribute it to her childhood experiences living off the land as she and her mother and siblings fled from Austria to Bavaria at the end of World War Two. She would probably tell a different and more accurate story, and a good one, so check it out if you are interested in seeing what fire can do to bring back native plants after a century of pastoral destruction.

That’s her on the left circa 1974 in this painting by my brother that he completed shortly before his untimely death last year, from a photo of the two of them in Mom’s rock garden:

Utopia means nowhere

I spent the first couple of weeks of our quarantine reviewing the copy editor’s mark-up of my new book. I turned my comments in last week, and it will be hitting the shelves late this summer, publishing gods permitting. Through a very different narrative prism, the book explores some of the same themes as this newsletter, trying to cultivate a little bit of utopia in the dystopia we find. I hope it lives up to the promise of this amazing cover by designer Owen Corrigan—unafraid to suggest that the sky turning pink is a sign that things are about to get better.

Failed State is the story of a lawyer trying to get justice after a corrupt American government has been deposed in a nation-breaking uprising, and of one community of people pursuing a more radical justice for the destruction of the American wilderness. This is a tough year for new books, but I hope its vision of a greener future will resonate with people interested in imagining other ways we could live after the fault lines of the current system are so starkly exposed. More about the book here at the preorder page if you’re interested, including updated creative copy that gives a crisp sense of the story.

Easter Armadillos

Bonus video for those who made it this far, an example of what lives on the other side of the fence—a trio of armadillos coming up for a Sunday afternoon forage. So far as I know, the only deadly virus these animal neighbors of ours carry is leprosy, but they won’t infect you unless you eat them.