Summer's end at the beginning of the Future

No. 160

“Did you read the first chapter of The Ministry for the Future?”

That’s what my sister-in-law asked me, after she and her kids settled into our daughter’s bedroom for the night on Wednesday, seeking refuge from the heat after the power failed in our neighborhood, and ours was restored before theirs. I had given her the book and two other SF novels when she started a futures-focused public sector job last year, after more than a decade in the fight as a leading reproductive justice activist in Texas. She whispered the question, as if she didn’t want her kids to hear it.

I told her I had, and understood.

“And then the sun cracked the eastern horizon. It blazed like an atomic bomb, which of course it was.”

So reads the sunrise at the beginning of Kim Stanley Robinson’s masterful 2020 climate fiction, which Jonathan Lethem sharply called “the best science-fiction nonfiction novel I’ve ever read.” The chapter features an American aid worker living through a catastrophic heat wave in late 2020s India, characterized by lethal combinations of high temperature and high humidity.

“The heat coming from it was palpable, a slap to the face. Solar radiation heating the skin of his face, making him blink. Stinging eyes flowing, he couldn’t see much. Everything was tan and beige and brilliant, unbearable white. Ordinary town in Uttar Pradesh, 6 AM. He looked at his phone: 38 degrees. In Fahrenheit that was—he tapped—103 degrees. Humidity about 35 percent. The combination was the thing. A few years ago it would have been among the hottest wet-bulb temperatures ever recorded. Now just a Wednesday morning.”

The chapter follows the scene as the aid worker does everything he can to help those around him, providing shelter and water as the multi-day crisis unfolds. The scene is grim, with a lot of mortality as conditions worsen, starting with the young and the old. By the end, he and others find their way to the dirty warm bath of the local lake, as the only path to survival. When he awakens the last morning, still half submerged, most of the people around him are dead.

I understood why Ana whispered the question, so her kids couldn’t hear.

We live in one of the fastest-growing cities in America, a city of exceptional but unevenly distributed affluence. And we all live in anxious expectation of the next power outage, worried for the safety of our children in a climate that is no longer really livable without the massive machine that refrigerates our lives.

The last really big outage happened in an extreme winter event, when the state power authorities chose to implement rolling blackouts to avoid a more catastrophic failure of the grid that would take months to repair. Leaving us to find out whether our homes would retain enough heat in the night for our kids to live through it.

When the machine conks out on a triple-digit August afternoon, it’s just an inconvenience. But as such events become more common and last longer in ever more extreme weather, it also feels like a preview of the scarier future you know has been coming. One in which the change in the weather is paired with the degradation of the institutions we rely on to maintain the safety and comfort of modern life.

Last summer was worse. I remember the June day I tried to go for a run despite the unusually nasty heat, and I learned for the first time what it actually feels like to do something active in the kind of extreme wet bulb temps climate futurists have warned us to expect—heat and humidity combinations that make it impossible for your body to cool itself. It was an awful lot like the scene Robinson describes. When every day feels like a bright and muggy summer afternoon right before it rains, but the rain never comes.

That morning I had seen a shooting star in the pre-dawn sky, as I stepped out from our buried house and looked up into the darkness above the front stairs. I was admiring Jupiter and Mars in the east when I saw the flash there arcing north by northwest as it burned out. It’s fun to imagine such a sighting as a portent of good fortune, but I found myself increasingly hard to convince.

That Sunday we had attended a kid’s 5th birthday party at an outdoor cafe in the suburbs at 10 a.m., presumably planned at that uncivilized hour to avoid the afternoon heat, but the mornings aren’t much better. The cafe had a native plant garden, and as I tried to catch up with our daughter I stopped to investigate a severed butterfly wing I saw in the cardinal flower. I noticed motion under one of the leaves, and when I looked closer I saw a mantis eating the rest of the fairy.

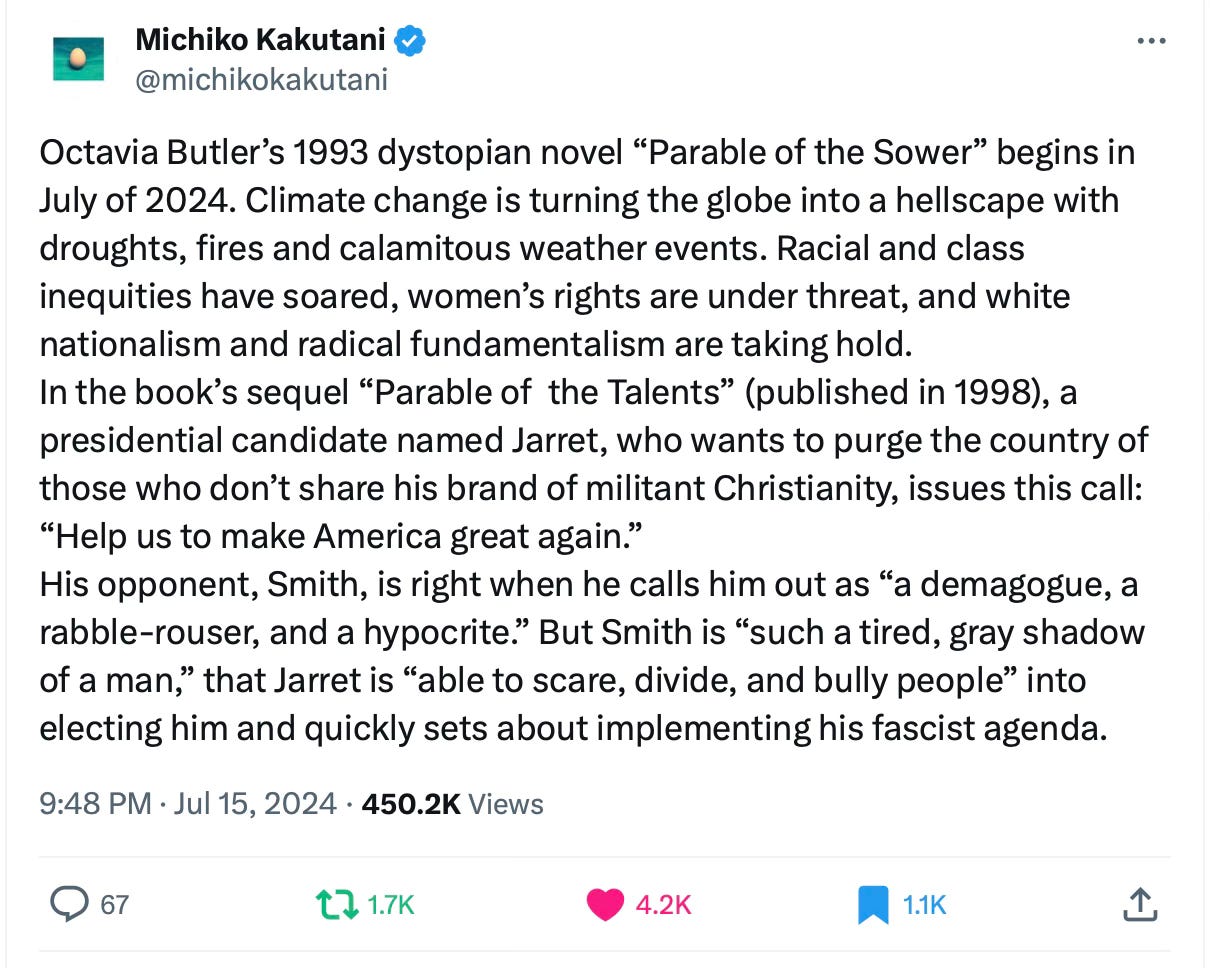

At the end of July, my feed was full of folks remarking on how we had arrived at the actual date—July 2024—in which the narration of Octavia Butler’s masterful dystopian novel The Parable of the Sower begins. One of the other books I had given my sister-in-law for her birthday. A story about a girl growing up in a gated compound in an environmentally, economically and socially collapsing USA, who realizes they need to hit the road and find a better place. A book that, in the moment, felt eerily prescient to many.

A month later, the mood of the feed is more upbeat and hopeful, as if the dystopian trance has suddenly lifted. Maybe because the discussion of climate issues got mostly tabled for the spectacle of people chanting “USA” at the DNC.

Kim Stanley Robinson’s first novel, 1984’s The Wild Shore, also featured patriarchal elders living in the ruins of the future talking about how they will “make America great again”—a line he, Butler, and the MAGA crowd all got from Reagan. In The Ministry for the Future, the American guy who survives the first chapter undertakes a different task: using his pragmatic can-do energy to advocate for the global cooperation and innovative policy tools we need to deal with the crisis that is unfolding in slow motion. You could almost call it utopian, in the way of understanding that utopia is not a place. It’s a decision we make, about whether we want to accept the world we find ourselves in, or work to make it better. A decision that does not involve waiting for institutions to act, but taking action in our own communities and everyday lives, and organizing to compel our public and private institutions to do what future generations need us to do.

My in-laws’ power was eventually restored Wednesday night, and they grabbed their stuff and went home. But we had the feeling it wouldn’t be the last time we would be helping each other out because extreme weather had provoked failed infrastructure.

Thursday was even hotter. After a gentle, wet July, the late-languishing part of the Texas summer had arrived when the landscape turns brown, the flowers all seem gone, and even the leaves on the mature trees look dried out and sick. And so I found myself freshly admiring the one drought-tolerant native that reliably blooms in our harshest conditions—a vine that thrives in the edgelands, on chain link fences and sun-blasted rights of way, sometimes on the other plants that have already browned out.

The plant they call old man’s beard doesn’t even look like a flower. It has no petals, just conspicuous stamens, and elaborate feathery grey-white plumes that unfurl from the seed pods as they mature. An alien-looking plant, one that looks like it was grown from the cover of some vintage sci-fi paperback. A reminder of nature’s resilience, and an early indicator, perhaps, that the ecological adaptations the future will require may be weird, led by the species that have already learned how to survive in extremes.

Friday was just as gnarly. But then around 5:30 the muggy air finally burped up some thunder and delivered the rain, a nice long storm that arrived at the end of the hot summer afternoon, the way it is supposed to. Or used to be, before we changed the weather in ways we may never be able to completely undo.

Texas appearances for A Natural History of Empty Lots

The dates for the Texas portion of the book tour for A Natural History of Empty Lots are coming together, and if any of these are near you, I hope you will join us:

Wednesday, September 18, The Twig Bookshop, San Antonio, with Jennifer Bristol

Thursday, September 19, Book People, Austin, with Jesse Sublett

Thursday, September 26, The Wild Detectives, Dallas (Oak Cliff), with Bonnie Jo Stufflebeam

More to come on other launch events to follow. Preorder promotion and details here via Timber Press.

Summer Reading

The September issue of Texas Monthly has an excellent cover feature written by Stephen Harrigan about the Karankawa of Texas and their efforts to reclaim their history and protect their ancestral lands.

The folks at Dust-to-Digital had an interesting recap this week from a workshop on ecoacoustics—paying closer attention to the natural and human-made sonic landscape:

Last week while I was recording the audiobook narration in a studio at the north edge of downtown Austin, I found a coffee shop in a new high-rise a block away, one of those places that is designed for the building tenants more than visitors from outside, but proved a convenient place to caffeinate and prep the text before each day’s session. On the last visit on Thursday I encountered the jumbled remnants of a WE WORK sign, hidden in a hallway around the corner from the bathrooms, and wondered what anagrams lurked in there, perhaps taking license to flip the “w”s into “m”s.

I’m keen to find a good longform backgrounder on this week’s story of the tragic sinking of the technobaron superyacht named Bayesian.

And for a dose of cold on a hot day, here’s the February 2021 report I wrote in the immediate aftermath of that week’s Texas winter storm:

Have a safe week.

Once again you have set my thinking machine down more new trails, Christopher, and wow, those photos, especially the mantis-eating-monarch (possibly a great subject for me to attempt painting), but you know, the thing that really got me this time comes at the end of your essay, that is, the sinking of the Bayesian, the super yacht owned by tech billionaire Michael Lynch who was celebrating his acquittal on fraud charges and the clearing of his name (oh, really? ); a sudden, totally unexpected catastrophic sinking of a supposedly unsinkable vessel (where have we heard that before) with the loss of 17 people, including the celebratory accused fraudster. I don't mean to satirize this tragedy, but, considering that he named his yacht after the mathematical idea that was the founding notion of his company (the one that he sold to Hewlett-Packard for what they said was at least $9 billion more than it turned out to be worth), my immediate thought was this: Is this the perfect film noir? Or is this a Greek myth? Or, did this really happen? I'm going to continue researching this story.

Glad you are voicing the audio book. Authors do it so much better than career narrators. Exception: Johnny Depp narrating a portion of Keith Richards’ memoir, “Life.” Keith started it, but apparently didn’t want to finish it. Still, the audio is more moving and authentic when it comes from the author.