Snow day sigils

It snowed here in Austin last Sunday, something that only happens every few years, and rarely with enough powder to stick. Usually when it does snow the flakes come at night and greet you in the morning. This storm came at mid-morning, and blew all afternoon, leaving a nice light blanket of white and the stillness that comes with it. Not thick enough to to leave a tracker’s record of the comings and goings of our woodland neighbors, though the mud that was left after the snow melted Monday morning provided some of that.

Monday morning I spotted a pair of mysterious aircraft flying over, headed north-northwest. Unmarked, windowless grey jets with four engines each, the kind of lumbering leviathans that look too heavy to fly. Their squawks didn’t show up on the smartphone Flight Tracker, further certifying the official and secret nature of the flight, but they looked like C-17s, the plane they call the Globemaster. Not as X-Files-adjacent as the “Doomsday plane” I saw the Monday before the election, but working on it.

I wondered if they were headed to the Naval Air Station at Fort Worth, where the adversary squadron command is based, and an old friend of mine used to work. From the stories he told me, it sounded like just the kind of place where they would get busy between an insurrection and a contest inauguration. A Navy base in the middle of the continent, full of senior fighter pilots who fly missions no one will ever hear about, the ones who aren’t being metaphorical when they talk about working “below the radar.”

The rest of the week, the sky was full of military helicopters coming and going from the airport, which used to be an Air Force base and still houses what the locals call the Texas Military Forces. After a while you learn to identify the choppers from the sound of the rotors before you even see them, the same way you can tell the difference between an osprey and a hawk, and a mockingbird trying to sound like a hawk. A Black Hawk sounds like Paul Bunyan chopping the sky, and nothing at all like a real hawk. A Chinook with its twin rotors sounds even heavier.

Saturday afternoon I heard one of those choppers coming up over the river, and when I looked, I saw a white heron and then a flock of ducks scatter before I saw the helicopter. While the birds may be disturbed by the movements of our ten-ton black metal bumblebees, they don’t seem otherwise anxious about what’s in the human air. As evidenced on Tuesday morning when the dogs and I walked along the river enjoying the fog, and came upon some of our neighbors who don’t have Internet connections chilling on the urban Colorado. The deepwater-fishing cormorants who mostly work the waters above the dam, and the herons who prefer to wade the shallows, sharing a log.

The sun was just getting above the treetops when we set out, headed east through the woods behind the door factory. We flushed a mob of whitetail, which the dogs smelled but only I saw. They were distracted by a new den they found, dug into the dirt at the edge of an erosion control gabion. We found more deer a little further on, scattering down into the floodplain, and I spotted what I thought was another up above us, in the old right of way. Then I saw its backlit silhouette running through the trees along the drainage ditch behind the construction supply warehouse, the one with the old TV wrapped up in the roots of a hackberry, and I realized it was a dog. A big one, on the loose.

In profile, it looked like a Boxer. One of those dogs without a real snout, not really made for the woods, where it’s all about the nose. A dog bred to perform a specific task for humans. In the moment, it looked more ephemeral than that, almost like some kind of proto-dog, a metamorphic Molossus. And like so many of the big dogs I see moving through the crepuscular edges of the urban woods, you could tell it wanted to stay as far as possible from any humans, or dogs under human control. Warier than a coyote or fox, but not as naturally gifted at disappearing in plain sight.

We followed the deer trails through the empty field behind the dairy plant, as the sun came on stronger. The invasive Johnson grass is dormant now, but the downy brome is already coming up, crowding out the early wildflowers. They mow that field a couple of times a year, and I wonder if they stopped, whether the native grasses might have a shot at retaking it. They still pop up in patches. The hawks love that field, where the telephone poles along the right of way provide perfect perches in the zone that connects the streets at the edge of town with the hidden woods below the overpass, which you can see and hear in the not-too-distant background.

Saturday morning I stepped out to find three of those hawks arguing over who gets control of the best pole. You can almost see the cranky in this one.

Further on, we came upon a recently abandoned camp much closer to the overpass. Mattresses, water-logged books, plastic bags of trash hanging from bare branches, a discarded prepaid phone named after the cricket. A while back the newspaper reported that our Attorney General likes to use burner phones, and I wondered if that’s his preferred brand.

The campsite was hemmed in by a thick cactus patch, which we navigated our way around, and then came upon a very old wall, demarcating a property line no longer recognized. The big chunks of concrete construction debris dumped around it somehow looked even older, the way they were slowly sinking into the floodplain, but the wall is the only thing there from the century before last.

The night before I had fallen asleep reading about female Druids, the Dryades who mystified the ancient Greeks and Romans, who couldn’t get their heads around the idea of a culture without patriarchy. It didn't last long after first contact, especially not after the beginning of the Christian era. It made me wonder how much of that change from mother goddess to heavenly lord had to do with social shifts associated with the rise of agriculture, and how much with the monastic eccentricities of early Christian ascetics and their wariness of our animal nature.

In The White Goddess, Robert Graves claims to crack the secret alphabet the Druids purportedly encoded from the names of the trees, but I’m not sure I buy it. You can tell it’s an imposition of our way of thinking on the enigmatic remnants of one that’s really almost totally erased, as gone as the trees that were cleared to make way for the pastoral civilization that replaced it and the urbanity it enabled.

There were a lot of wild tires along the river, some of them in it, so old that you wondered if they could become fossils. On the rocky beach where they used to dredge gravel for the aggregate plants, you could see the bluebonnets starting to come up, winter hardies coated in a frost they would soon drink up, telegraphing the persistence of spring even on disturbed land.

As we walked back toward home, we came upon one last little dump of snow, on some fragment of linoleum tile the floodwaters had left at the base of a big hackberry. In the picture I took, there’s a rainbow I didn’t see when I was there, like some hidden spirit. It made me wonder what the Druids would make of the trees that grow through our trash.

It’s not about the animal

The dog so emancipated it looked like a cryptid got me thinking about the legal doctrines that allow us to make another living being our property. I hadn’t known that Boxers were essentially bred precisely to perpetuate our exercise of the rule of capture, dogs whose weird brachycephalic heads are designed for the express purpose of holding our prey until the hunter arrives.

The rule of capture has been a particular preoccupation of mine in recent years, as I have tried to crack the code of our dominion, and understand if there’s even a way you could unwind the structures of how our entire civilization is based on legally sanctioned control over the reproduction of others—plants, animals, and people. I wrote an essay that riffs on it, only to see the essay morph into a horror story. And then I wrote a whole book that took the doctrine as its title, and riffed on it in different ways.

The rule of capture is one of the first things they teach you in law school, in the class they call Property, which is mostly about rights in the land, but starts out with a short little case about who gets to take the living things that are on the land. The case is about a fight between two rich guys over a who became owner of a fox that they separately chased on to the commons of the town in Long Island where they lived—land that the court described as “waste and uninhabited land,” revealing much about the way American law thinks of the wilderness.

When I went back two decades and change after law school to reexamine this seminal fundament of our jurisprudential brainwashing program, I came across an outstanding work of legal history in the Duke Law Journal by Bethany Berger, Wallace Stevens Professor of Law at the University of Connecticut—“It’s Not About the Fox: The Untold History of Pierson v. Post”

Pierson is a canonical case because it replicates a central myth of American property law: that we start with a world in which no one has rights to anything, and the fundamental problem is how best to convert it to absolute individual ownership. The history behind the dispute, however, suggests that the heart of the conflict was a contest over which community would control the shared resources of the town and how those resources would be used.

It’s a fascinating social and economic history as well as a legal one, digging deep into the American struggle with the idea of the commons, and a rare example of a law review article I would recommend as worthy reading for non-lawyers. Not just because her professorship is named after our greatest lawyer-poet. Here’s a direct link to the full PDF at Duke.

It does not solve the question I have been pondering this weekend, of who owns the Bowie knife-sized great blue heron feather baby and I found at our doorstep Friday morning.

Further reading

Related to the kinds of cultural conditions that produced female Druids, my colleague the SF writer and science journalist Annalee Newitz has an excellent roundup at the NYT of all the recent learning on how common it was in human history for women to be hunters and warriors, a topic I talked about here a while back. Annalee also has an excellent new science-focused newsletter on this platform, The Hypothesis, this week’s installment of which is a fascinating visit to Çatalhöyük, the 9,000-year-old site in central Turkey considered the world’s oldest city.

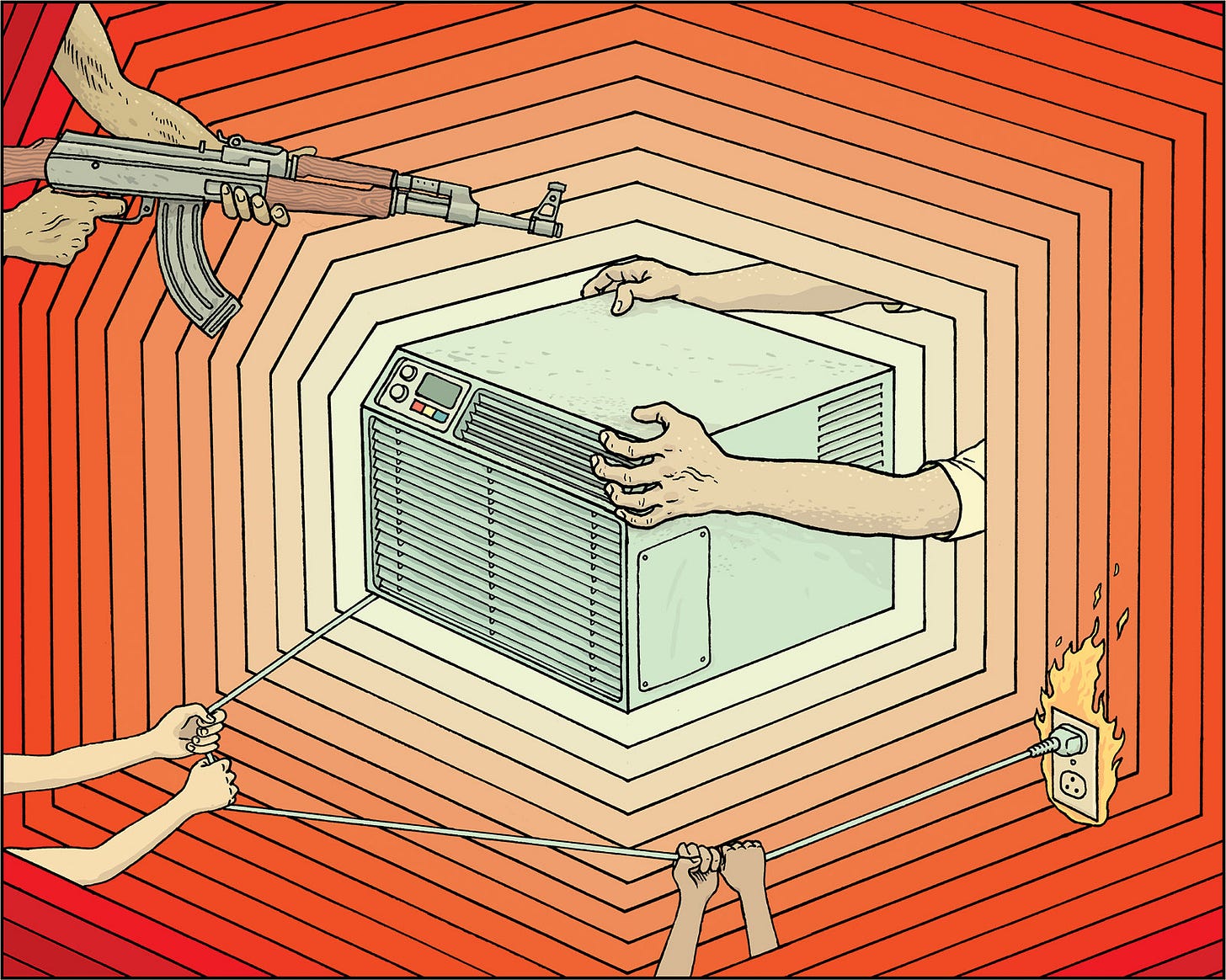

The December 17, 2020 issue of The New York Review of Books that was waiting for us when we returned from the winter holidays has an excellent piece by Bill McKibben about Kim Stanley Robinson’s latest novel, The Ministry for the Future. The piece is both a book review and a consideration of our climate future, with some provocative but incisive commentary on things like the current obsession with space colonization. Plus, it is illustrated with the above graphic by Anders Nilsen, one of my very favorite graphic novelists and comic artists, whose work often explores urban and suburban nature.

This week I got to talk with the writer Nick Kocz about my own latest novel, Failed State, and about what it was like seeing dystopian scenes so similar to the ones I explored in my last three books play out live on TV news: “Christopher Brown: A Utopia Grounded in Realism Is A Tragedy,” at Ridiculous Words.

In a similar vein, Andrew Liptak has an interesting piece this week on those same sorts of parallels: “When dystopian fiction comes to life: What science fiction tells us about our current moment in 2021.”

Bonus baby walking stick

For those who made it to the end, here’s a very tiny female creature I found in our kitchen yesterday, which will grow into one of the biggest insects in North America, the Texas walking stick. For scale, that’s a paper towel she’s on, which I used to transfer her to the outdoors. At maturity she will be the size of a skinny human finger.

Have a safe week.

I keep thinking that someday I'd love to chat with you about Brehon Law (the law of the non-Roman, anti-Norman Irish), which I delved into when I was doing research in the Republic. I'm sure you'd raise some intriguing questions...

I don't know if this helps, but Melville's commentary on British law regarding whales as property, makes me wonder if anything has changed in the intervening years:

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/2701/2701-h/2701-h.htm#link2HCH0090