Reseeding the flyover

And some new edgeland country from The Tender Things

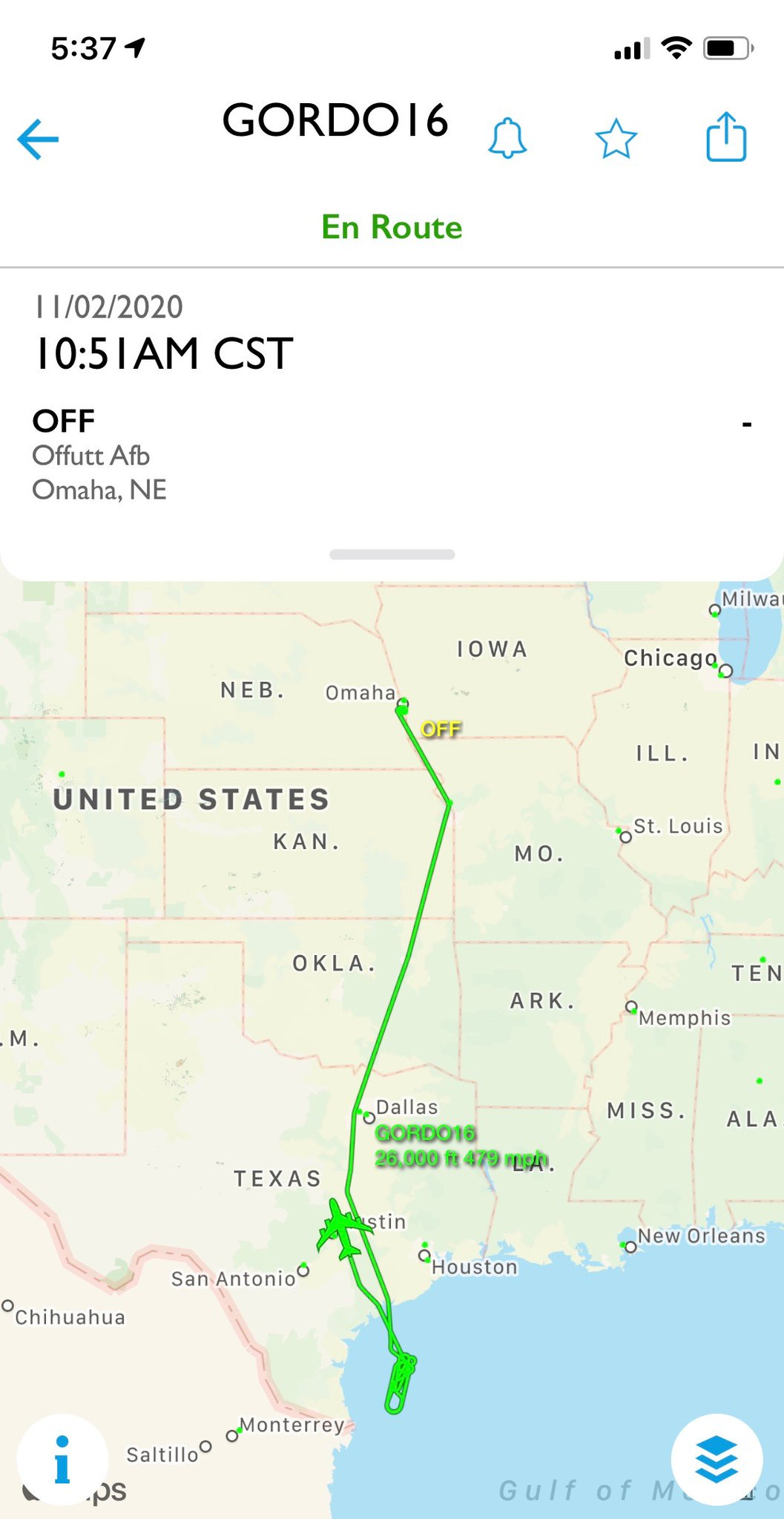

Monday night I stepped out of my trailer for a break around a quarter after five. It was a beautiful autumn day, clear and warm, and in the eastern sky the faraway planes glistened in the blast of light the sun releases just before it begins to disappear over the horizon. They were like shimmering little mirages, everyday aircraft that had the wonder of their overweight lumberings through the atmosphere dialed up by an ephemeral moment in nature, no bigger to the eye than the dragonflies zipping around closer by. And in that rare light, you could see one of the planes was one of the ones you are not supposed to see. And yet there it was, on the business traveler’s handy smartphone flight tracker app, tagged with the squawk box code name GORDO16, the name a science fiction writer might give a friendly Canadian robot.

The commercial flight monitoring apps used to never show the military aircraft. Now they do, but with alias call signs and no flight plans. GORDO16 had taken off that morning from Offutt Air Force Base south of Omaha, in the ancient floodplain of the Missouri River a few miles from the little town where my dad grew up. It had then spent the whole day in international waters over the Gulf of Mexico, circling, and was now headed home. It was a big plane, bigger than a typical airliner, and you had to wonder.

I shared the images in my feed, noting that strange aircraft feel extra strange on portentous days like the day before an intensely contested presidential election in which in feels like the future is on the line. A savvier person in my network identified GORDO16 as a Boeing E-4 “Nightwatch” aircraft: one of the four “doomsday planes” designed to serve as flying command centers in the event of a national emergency. A 747 reconfigured to be able to survive a nuclear war, with a distinctive avionics hump atop the fuselage that you can clearly see in my long lens capture above. The E-4 is one of the only military aircraft to still rely entirely on analog instruments, because they are better able to withstand an electromagnetic pulse.

As my mind spun out X-Files plotlines, the same guy who ID’d the aircraft pointed out that Election Day was one on which the national leadership would likely be distracted, creating an opportunity for hostile actors, and a good time to take the doomsday plane out for a ride just to make sure everything’s working.

On the night of the elections, I managed to not check the news, instead reading my friend Tom’s brilliant new comic Cartoon Dialectics 2, about how “Apocalypse is the suburb of Utopia,” and a couple of ghost stories in the M.R. James collection that had just arrived. I remembered the elections of 2000, back in the days when I had a TV, and for some reason anticipated another night when they wouldn’t know the winner.

The morning after Election Day I went for a walk with my friend Jesse Ebaugh, the guy whose mushroom foraging skills I reported on last week.

Jesse and I had been talking about getting out for a walk in the woods for months, since right before the lockdown came down in March. He and his wife Mishka (an amazing artist and designer) were our neighbors for many years, and we both got married on this street, and spend big chunks of our time exploring the hidden wilderness around this neighborhood at what used to be the edge of town. Wednesday morning we finally made our meetup happen, at the trailhead of a new secret path Jesse discovered over the summer.

To get there you have to navigate through a labyrinth of tollway construction to a very old road that follows the meandering path of one of the major creeks near here, the creek the earliest white settlers followed as one of their main routes to the Hill Country. That old path, which was probably an Indian trail, became right of way for a railroad that the city more recently turned into a bike trail and greenbelt. A section of it is still right of way for a transcontinental fiber optic cable, and as we set out on the first section of jeep road you could see the line markers there in the brush, carrying packets of news, but we were focused on all the deer, as was Jesse’s dog.

We talked while we walked, about our loved ones, about secret paths and the art of getting lost without getting busted for trespassing, and about our experiences of pandemic, comparing and contrasting the challenges of launching a record and launching a book when all the normal outlets for promoting such works are closed.

We crossed areas that had been cleared for the bigger rights of way of the power transmission pylons that line up across the landscape like giant robots, each of which were full of black vultures. Jesse pointed to a nearby hilltop where one of those big tree-eating machines had recently come through and cleared the area for new construction. Deeper in, we passed a small creek that Jesse surmised was discharge from the nearby industrial facilities tucked into the woods behind the highway.

We came upon a crossing where you could see the outbuildings of one of those fabs. The “Countermeasure & Electromagnetic Attack Solutions” division of a British defense contractor, which is getting ready to expand its Austin operations now that the Army has headquartered its new “Futures Command” here in offices it shares with the administrators of the University of Texas System. The clickbait bros who dominate life downtown now (or did before pandemic) probably don’t appreciate the extent to which Austin’s tech business evolved from defense applications spun out of the university, especially during the long war when the President was from here, after his boss got shot in Dallas. Seeing that place, and then researching its current activities after I got home, reminded me that the only American futures that really get the attention of the state are military futures.

Not far from there we crossed the bike trail, and dodged a couple of Spandex-clad men cruising by on their expensive bikes, here in the town where Lance Armstrong can still be seen in the wild if you know the right parts of the Greenbelt to ride. Jesse showed me the next trailhead, and our trail got more rugged, basically a deer trail along the edge of the creek.

The woods got a lot thicker, and older. The creek was dry, but full of life signs, and the trees that grow up out of its vessel were huge, providing us a high, shady canopy. We kept talking, and one of the hawks talked back as it left its perch above the creek bed. We came into one really beautiful grove of tall old oaks and inland sea oats, on a secondary terrace of the floodplain, one of those sacred spots that seems like an intact remnant of what was here before those white settlers started riding through.

As the understory opened up, the deer got bigger. We saw one especially big stag, right before we came to a crossing where Jesse indicated the side trail led to a mysterious camp, the real thing he had wanted to show me back in there. It was more than a camp. It was a little house someone had built deep in the secret heart of the urban commons, using bought materials, with chicken wire windows to keep the animals out and a high fence reinforced with cut bamboo, reed screens and a padlocked gate to keep the humans out. And a little stand with fresh snacks and beverages to tempt edgeland Hansels & Gretels.

Not long after that, I had to ruin the woods with the capitalist karma of a ten-minute conference call, and by the time I was done, we were back out in the open. You could see the expansive patches of goldenrod that have just burned out their autumn blooms under the power pylons, fertilized by the excrement of all those vultures up there grooming each other in the bright morning sun. The smell of it punctuated the end of our stroll, and brought the revelation of how highway roadkill helps generate the new life of the year to come. Life that, as early as November in this unfrozen corner of the continent, is already starting to grow.

On Thursday morning I took our dogs out for a walk in the field behind the dairy plant, a high terrace above the floodplain of the Colorado River that was subdivided and leveled as an industrial park many decades ago, but has somehow managed to survive as something more like a real park. The land is owned by the dairy company, but it’s next to a wildlife preserve, fenced in from the street but open to the woods. They mow it twice a year at most, and the wildlife use that cover to provide a safe transition between the forest and the urbanized zone beyond the fence.

I spotted something shiny there in the Johnson grass, and wandered in after the thing, dragging my dogs who were more interested in tracking the scents on the ground. I thought it was some kind of bag as I got closer, and then I realized it was a balloon. I see a lot of helium balloons floating by around here, maybe something about the way the air currents follow the river. But this wasn’t the aerial flotsam of a kid’s birthday party. It was something different. A melancholy message in Mylar, snagged on its way to heaven:

Friday morning as the election results began to settle, we took baby and dogs for a walk on the street, and I saw another strangely heavy windowless plane moving in our periphery, with markings I did not recognize. I looked it up, and learned it was part of the new Amazon Air fleet—a 767 cargo plane delivering a load of consumer goods from San Antonio, a place so close it would be almost as fast to drive. It was the most dystopian auspice of an intensely dystopian week, a reminder of who really owns the future, no matter who wins the political horse race.

That night, as we waited for the victory speech deferred, I stepped outside and heard the coyotes in the woods howling at the siren of a police car working its way down the nearby highway. On Saturday morning, the news reminded me to order some fresh Native American Seed to help germinate a better 2021.

Reading list

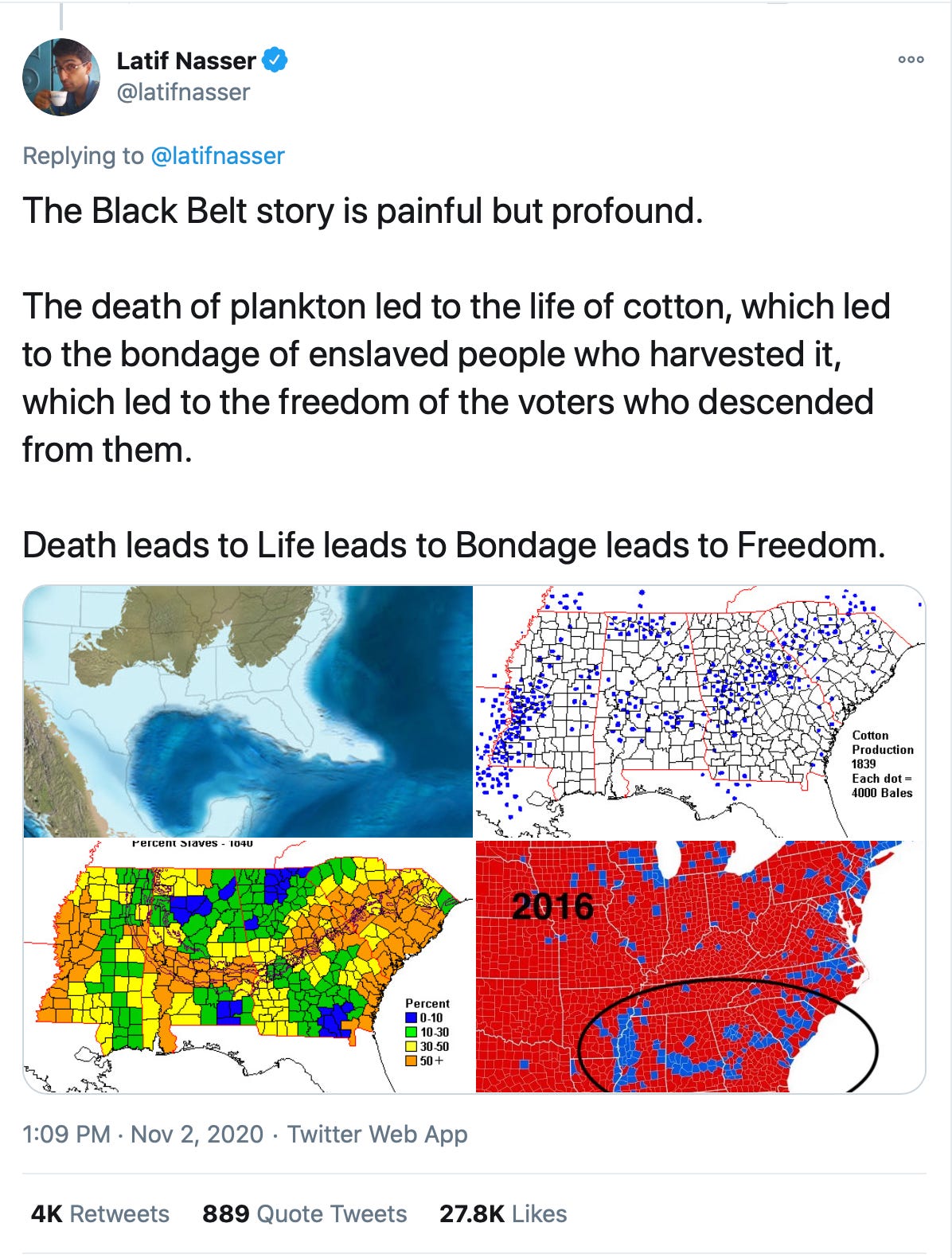

For a natural history perspective on the election, grounded in deep time, I highly recommend this remarkable Twitter thread by the writer Latif Nasser, showing how one particular swath of the blue-red electoral map is tied to the prehistoric geology of the South, and the things that were done to exploit the remains of ancient life in service of plantation profit:

Artemis of the Andes? Amid all the political noise as we waited to hear if a woman would become Vice President, Thursday’s news had the story of a 9,000-year-old teenage girl in the high country of Peru the discovery of whose remains is shaking long-held assumptions about gender roles in early human bands of hunter-gatherers. “Ancient Remains in Peru Reveal Young, Female Big-Game Hunter,” NYT, Nov. 4—for the full story, read the research paper “Female hunters of the early Americas” in ScienceAdvances, by the scholars involved in the discovery. This follows research published earlier this year on discoveries suggesting that women in similar societies in ancient California and Mongolia served as warriors.

If you’ve had enough of the USA this week, CrimeReads has a new piece from me on how to escape it in style—“No Badges: Running for the Border in American Noir.”

A Public Service Announcement from The Tender Things

My walking buddy Jesse Ebaugh is a Field Notes reader and booster, and after this week’s excursion he generously offered to use this newsletter as the platform to share his band’s latest video, a project whose original release was interrupted by pandemic. Jesse also shared some of the things we talked about on our walk, in his own words, about life outside, writing music, reading poetry, and enduring pandemic as a working musician. The rest of this newsletter is his:

I was born to the woods, a baby in a backpack living out of a tent at tree line through two Colorado summers, an adolescent roaming the eastern woodland forests of Pennsylvania, fishing for trout and trekking. Music drew me out of the wild and into the city as a young man, but always with an eye to the horizon, regularly cutting out to the Rockies or the lakes of Ontario to recharge a thing that could be touched no place else. It’s a difficult lifestyle to reconcile, music and the outdoors, they seem to occupy mutually exclusive space, save a few wild west tourist town bars or summer festivals. My daily need for a dose of the outdoors, my most ritual of habits, demands that I find nature quickly in my urban routine. In every new town (I’ve moved many times) my explorations begin in the manicured parks and green spaces, but those spaces always lead to the edge lands, the strips along river levees or along bottom lands earmarked for storm water catchment. I’m drawn into these spaces by curiosity, but more importantly, I am promised measures of solitude and discovery that are not available in the public space. It’s here that I forage for ideas daily, notebook wet with sweat in my breast pocket on hot Texas mornings.

Much of my career I’ve been a sideman. A sideman is a player in the band, backing a songwriter or a singer, joyfully slogging out the craft of the working musician, recording, performing and living the traveling life. I’ve been fortunate in my labors to be involved in projects that have been both fulfilling artistically and allowed me to eke out a living as an artist. It’s an uncertain arc of career for sure, fraught with anxiety and thrills. A few years ago I began to feel a bit like a charlatan, for not giving voice to my own ideas and perspectives, so as a matter of soul care I struck out on my own for the first time. Kinda crazy to change tack so far along in the game, but I had begun to lose sleep wondering why days seemed like they were just blowing away as from a day calendar in a windy movie.

Slowly, a body of songs began to emerge. I started recording in the homes of friends, recording vocals in my own dressing closet. A band began to gel, The Tender Things, comprised of friends I had longed to play with but couldn’t due to my busy schedule touring with Heartless Bastards, a band I had served for a decade.

Soon the new band was running the circuit, trying to attract the attention of label execs, and beginning to establish a name at a national level. I threw a Kickstarter campaign, and was able to finance the recording of How You Make a Fool (my most recent effort) at a world class studio, run by a friend I had longed to work with. I released that record straight into the beginning of the pandemic.

I raged at my misfortune in the early weeks, struggling to come to grips with the reality that the world’s situation was more dire than my own aspirations for maintaining the trajectory of my project. As weeks turned into months, the project slipped away, and I found inspiration coming ever more slowly. The struggle became finding the inspiration to even be creative at all, when encountering the daily tsunami of horror of pandemic and politic. In defense I turned toward books, devouring things long populating my shelves, and discovering poetry anew. I found myself particularly sensitive to things I found in Louise Gluck, John Berryman, Dylan Thomas, Stevie Smith, and Arthur Rimbaud.

I held back the video for Sister Elizabeth, the lively lead track from the new album, expecting to encounter an opportunity to celebrate the video release with a performance of some kind, but it’s not looking like many opportunities are on the way. The role that this song plays in the context of the band is as a “thesis” song, one which, for many reasons, expresses the aesthetics of my songwriting and the mission of the album. I’ve long thought that first tracks on albums should exhibit this characteristic, and I love how it sets the tone for the album, How You Make a Fool.

((While we were walking Wednesday, Jesse mentioned that his mom was counting votes back home in State College. Turns out it’s a better day to crank some upbeat Pennsylvania “hippie country” than I expected:))

“Sister Elizabeth,” from the album How You Make A Fool by The Tender Things, available on Spaceflight Records.

Jesse Ebaugh

Sweet Gary Newcomb

Barbara Frigiere

Matt Strmiska

Ricky Ray Jackson

Blake Whitmire

Follow The Tender Things on Instagram

Video:

Director — Sam Wainwright Douglas

Cinematographer —Andrew Alden Miller

Visual Effects — Robert Mustachio

Have a great week.