Primrose and pandemic

Spring arrived in earnest this week. We had some good rain, and the wildflowers started to pop. And by the end of the week, as the world started to feel uncomfortably similar to the dystopian novels I write, I found myself wondering which of the wild plants growing in and around our yard are edible.

The thought first hit me on Thursday. That was the day the sense of pandemic panic started to really sink in, but our neighborhood vegetarian taqueria named after an R. Crumb comix character was still open, and as I forked my baby spinach I realized how much it resembled the leaves of the evening primrose I had been weeding around on our green roof that morning. When I got home, I looked it up, and sure enough, the experts say it tastes just like spinach—especially if you eat it before it blooms.

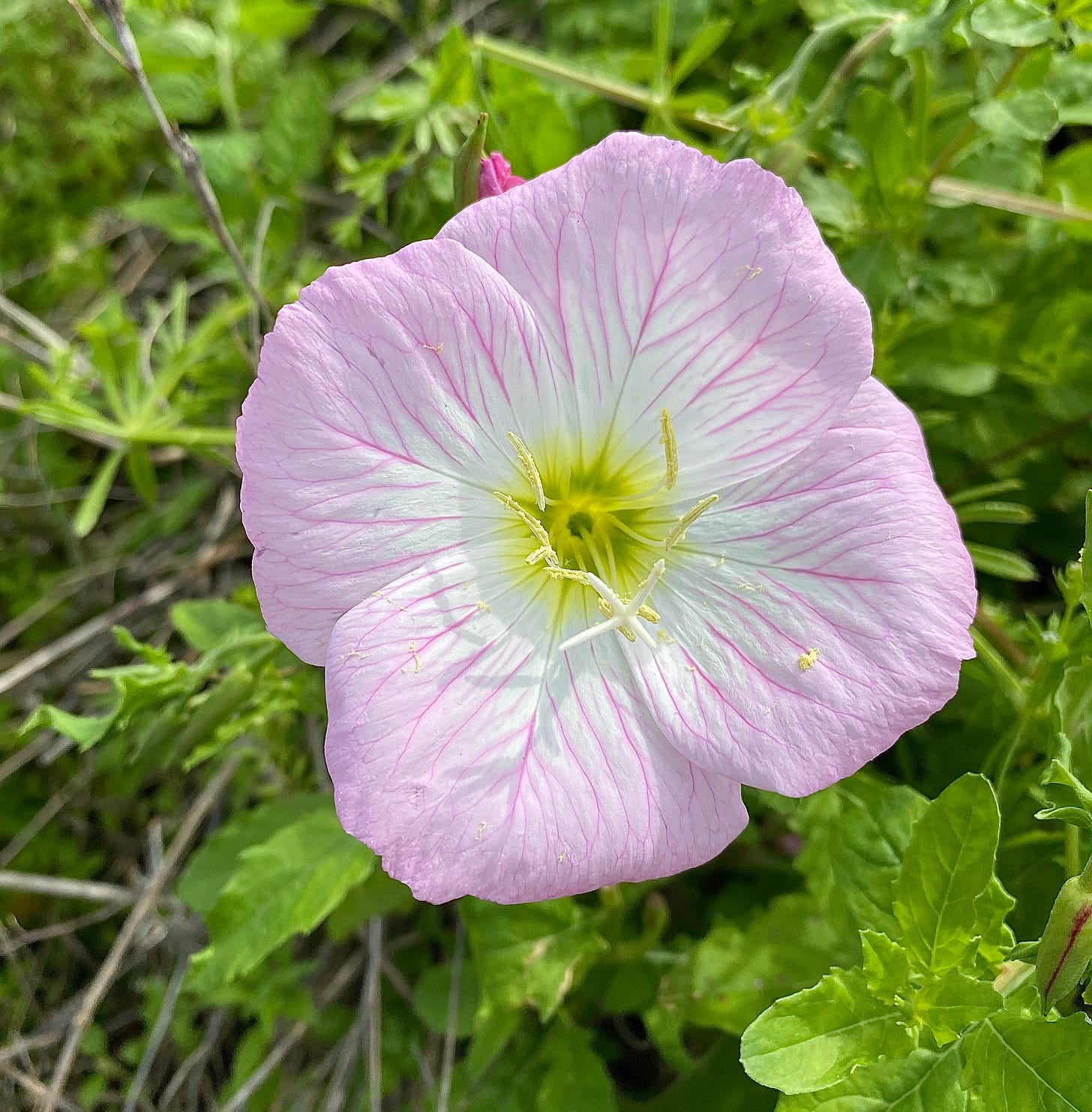

Its flower looks like a fragile pink buttercup, but the primrose is a crazy hardy plant. My neighbor the botanist says she has had little luck getting it to grow through deliberate cultivation, but it seems to thrive in wild fields no matter how many invasive grasses are around. It’s one of the first of the native Texas wildflowers to bloom every season, and you always see the pink blossoms in the roadside ditches before the first mow. I haven’t tried it yet, but after the apocalyptic scene I saw at the grocery store Friday night, a wild primrose and dandelion greens salad sounds pretty good.

One of my favorite books on urban nature is The Unofficial Countryside by Richard Mabey, a very English walking tour of the ecological bounty of the urban periphery of early 1970s London. But the book he wrote before that is the one I have been thinking about this week, the one I have never read—Food for Free, a hippie era directory of the wild food that can be harvested from the pockets of nature inside the city. There are other books like that, full of knowledge we mostly ignore about the edible plants of this hemisphere, but few of us learn what they have to teach. That’s knowledge we don’t need, as long as there’s food on the shelves at the neighborhood grocery.

On Monday, I was in meetings downtown. By Friday, I was thinking about whether my mediocre skills as a fisherman would serve my family and me in a pinch. Whether the prepper-grade water filter we have really would allow us to make water hauled from the nearby river drinkable.

A month ago, I was finishing a novel set in an America in which the agricultural system has failed. That’s just background for the main story, and it’s a worldbuilding element whose importance I didn’t appreciate until I was far along with the project—an effort at conjuring utopia. But if you grow up in the Midwest as a kid who likes to get outside, it’s an easy concept to dial into. When you’re young, it’s just the experience of going out into the country looking for wildlife and finding only crows and cows. As an adult, that observation matures into the revelation that our entire civilization is built on the enslavement of nature, and that at some point the Malthusian corrections are bound to happen.

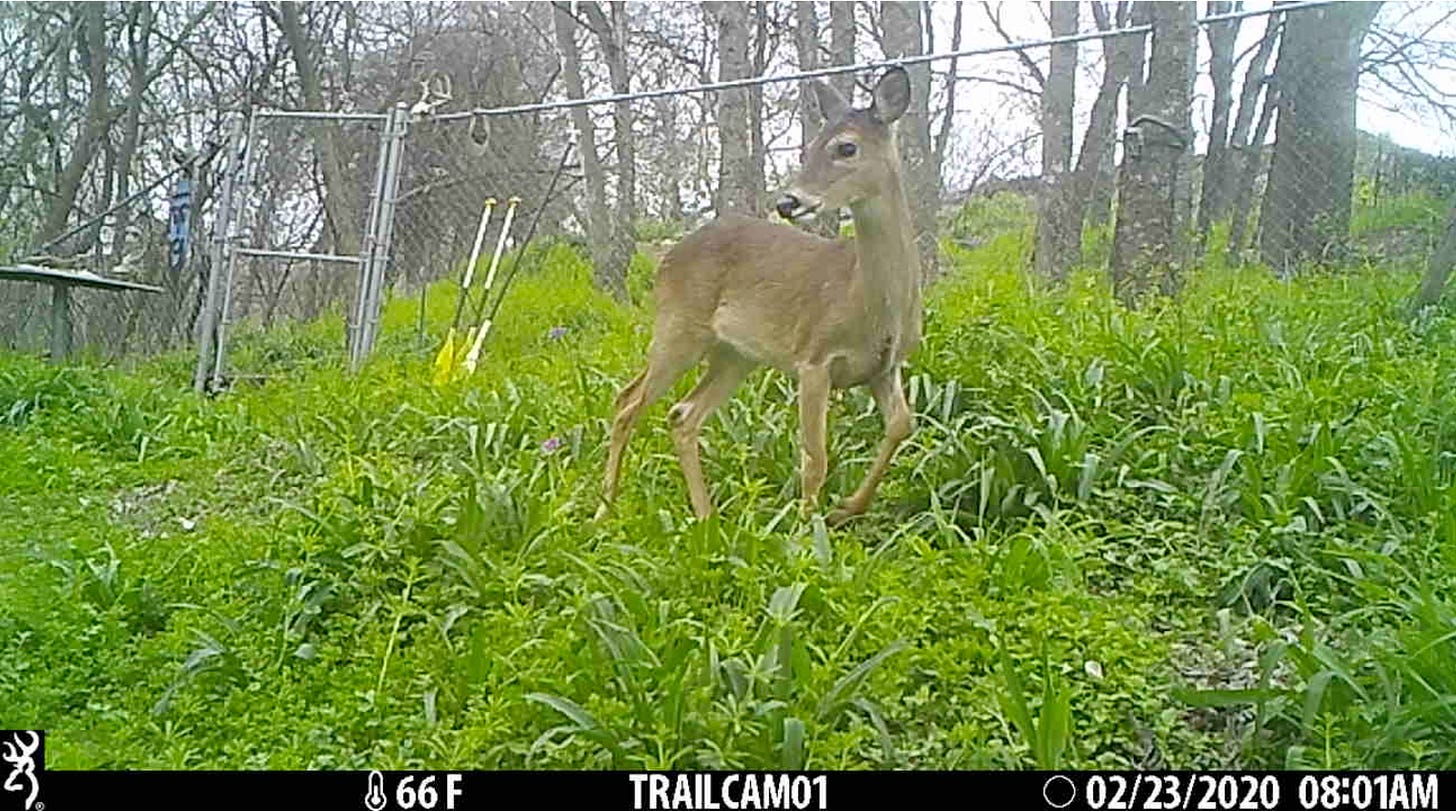

I saw the first baby snake of the season yesterday morning, wriggling around on our patio. Not long after that, I saw what might have been its six-foot-long mama slithering past our front steps. And I wondered how snakes learn to find their food. If they need their parents to feed them, like the cardinals that nest in the cross vine that hangs off our roof. If the baby snakes are like the baby deer I see this time of year, chomping away on the sticky weed that fills the empty lot behind the door factory, seemingly figuring out on their own that there is food for free.

The inevitability of springtime and new life is a reassuring thing, especially in times of extreme anxiety like the present moment. It has a deeper lesson, that the ecological systems that make it possible are the real foundation of our ability to survive and thrive. It’s almost scarier than the fear of the virus, the revelation of just how fragile the complex systems of political economy are that support our lives. Then I remember the weird news features from the nadir of the Great Recession, about the people who had learned to feed themselves in large part by foraging the gardens gone wild of suburban houses that had been abandoned after the real estate market collapsed.

To go from essentially normal 21st century life to the very real fear of imminent mass plague in the span of a week is not a fun experience. But it does remind me of the evidence that crises like these usually bring out people’s better natures. That as much as the media focuses on stories of hand sanitizer hoarders, when the state fails, people usually do a pretty good job of helping out each other. And that we are as resilient as the natural systems that persist all around us.

I am going to try to keep writing these field notes as we get through this, perhaps as one way to make connection in time of isolation. All the pictures will be from the week, as are these.

Take care of yourselves, and your neighbors. And remember that social distancing doesn’t mean you can’t go outside.

As a bonus, if you want something a little more utopian than what’s in your feed, but still germane to what’s going on, you might check out this Rebecca Solnit piece on how to find hope and community during crises like these.

And one last photo, of the huisache trees in bloom. These blossoms only appear for a couple of weeks, but when they do, you understand why the French use them for fine fragrances. The name comes from Nahuatl, for the spiny branches, but they can heal as well as hurt.