Prepper dreams of edgeland wine

A spider bit me in the face Saturday morning, after I stepped right into its web. I could feel it there right above the orbit of my right eye, and pinched it in my fingers. A little one, not anywhere near as big as the orb weaver I found by our front steps Friday afternoon, and presumably one that’s officially harmless to humans. I couldn’t find any bite marks, but it was a bit achey all afternoon. A good reminder to be more alert in the woods.

It was the first time I’ve taken our new ridgeback puppy into the woods, which was the main cause of my distraction, trying to get him used to the long lead. We were doing a bit of foraging, seeing what might be growing in the secret forest behind the factories, as a surprisingly cool and wet August settles in.

One of the things that makes these urban woods so different from others I’ve known is the proliferation of mustang vine, a native grape that climbs the trees all summer long, and just gets thicker and thicker over the years, quickly barking up as it grows into thick woody tendons that pull taut, sometimes connecting tree to tree, or pulling high branches back toward the ground. Their silhouettes give the forest a gothic quality.

So do the bones.

February’s weeklong winter weather event took out a lot of flora, including some big trees, and fungal shelfs are appearing early on the rotting trunks of new deadfall. The patches of prickly pear behind the construction supply warehouse are coming back to life, with a few fresh green paddles sprouting from the melted gray mass spread across the edge of the old roadbed. The chile piquin is starting to fruit along the fencelines, and a few late blooming wildflowers are popping up in the shadows of the drainage ditch.

Back up top, the mustang vine has taken over all the dead retama in the right of way. Those spiky green natives live fast and die young even without the aid of sustained deep freezes, but this year’s is a more bountiful crop of bare brown structures ready to be refoliated by an equally fast-growing vine. It’s coming up especially thick on the dead tree whose branches still hang over our old shipping container, with some of the leaves starting to crawl over the hatch. Outside the fence, you can see how it has taken over the whole zone here at the end of the road, even beginning to grab onto the cables that carry the high-speed data of a half-dozen ISPs.

Those vines have fruited in thick bunches over the past few weeks, ripening to a deep purple. Like a lot of wild varietals, mustang grapes have a reputation for being gamey—“usually bitter, even irritating,” according to the Wildflower Center’s profile. They taste pretty great to me right off the vine, at least this summer’s crop. It makes a killer jam, and a couple of weeks ago some forager friends brought over their latest vintage of mustang wine made from around here, and it was pretty dang good.

As we drank the wine, we talked about our shared interest in trying to harvest the rugged legumes of the mesquite trees one often finds near the retama. Honey mesquites are gnarly trees, growing slowly in crazy contortions, with thorns that can pierce a car tire and a remarkable capacity to handle heat and drought. This time of year, they spawn what look like long yellow pea pods. The certain sign of their readiness to eat is when the feral parakeets arrive en masse, pigging out on the flush branches and tossing the husks like empty beer cans. You often hear them before you see them, the chattering of their high-pitched blurps audible from faraway, a noise that makes you wonder if it might be part of their adaptation to the cell phone towers where they build their giant multifamily nests.

The parakeets eat the seeds, discarding the husks, but it’s the husks that are most useful for us. The Indians of the Southwest used them to make cakes and meal, and online recipes abound for ways to grind them into a nutty flour. When you learn that the tree’s common name is a Hispanicization of the Aztec mizquitl, it gives you a deeper appreciation of how ancient are the natural sources of sustenance that persist in the urban landscape of the borderlands. Even if you’re the sort of person who finds the factoid makes you wonder if there’s an Aztec connection to that Smallville trickster Mister Mxyzptlk.

It’s felt a lot safer in the creepy woods this week than out in the human domain, as Austin’s intensive care units fill with unvaccinated Covid-19 patients who contracted the Delta variant. But life goes on, and I did make a quick grocery store run last week. In the checkout aisle, between Bob Ross and Simone Biles, I found this guy, and decided to shell out the $9.95 to take him home.

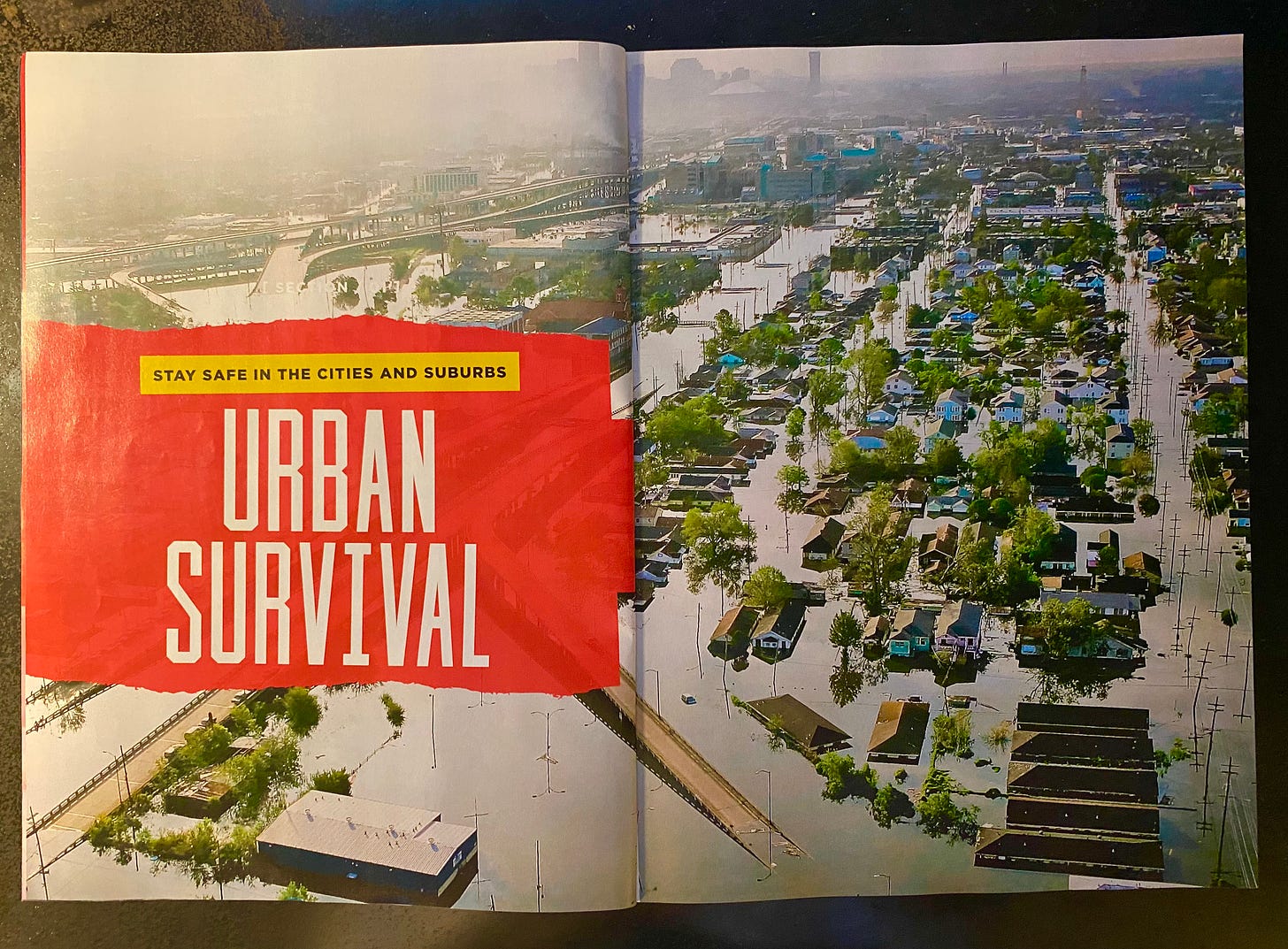

Prepper Survival Guide is a publication of the Outdoors division of Centennial Media, Inc., a Miami-based publisher that specializes in so-called “book-a-zines,” a format that has apparently flourished as Internet-era magazine circulations have plummeted. The editor and contributors all appear to be freelancers, and the voice is that of the paid posting, a generic infomercial prose that falls far short of the adventurous promise of the graphics (most of which, a review of the masthead reveals, come from Shutterstock). And while the impulse grocery store buyer might be lured by the daydream of raiding the aisles after the disaster, what’s behind the cover is more like an insider’s guide to getting by in contemporary Houston.

The stories cover the gamut of basic survival skills, with pieces on urban wild edibles, how to handle extremely hot weather, how to find useful things around town when the supply chain collapses, how to handle dehydrated foods, how to care for your feet and avoid trench foot in the drowned city, and, most importantly, how to start a fire—sometimes with suggestions that look like they might require some DIY burn care.

Like any outdoor magazine, half the content is gear reviews that make you wonder if the manufacturers are paying for placement. Prepper’s reviews are heavy on the survival tools, like the Adventure Medical Kits Trauma Pak III (“everything you need to secure a tourniquet”), 5.11 Tactical shorts (shorts are not what I would wear to the end of the world, but who’s asking), Spearo XO Sunglasses (“the durability to withstand the many faces of Mother Nature’s fury”), and the Ninja Wilderness Survival Guide. That, and all sorts of modern versions of primitive weapons, with a TSA surplus bin’s worth of carbon black multitools, a review of police riot shields that evaluates their adaptability to person-to-person combat over the last stores of food, and a totally insane collection of a dozen next-gen metal truncheons, including the Streetwise Barbarian Stun Baton Flashlight, which looks like a cross between a Mag-lite, a medieval mace, and a Taser ($45).

There are articles about how to drive like a real-world road warrior, how to prioritize your needs in an emergency, and how to stay alert when roaming the disaster area. But the most notable stories are the ones about how to scan the people around you for potential threats, and how to spot signs of human trafficking among your neighbors. I wonder if, in any of the other eleven issues, there is a single article about getting to know your neighbors, and building the structures of community and mutual support that are the true path to successfully managing through a real crisis, aggregating a diversity of individual skills.

As a lifelong consumer of end of the world fantasies, I can appreciate the allure of the narrative this slick zine is selling. As a teen dungeon master, I had tremendous fun mapping out the post-apocalyptic ruins of my otherwise boring Midwestern hometown on huge sheets of hex paper. I couldn't find many who wanted to visit them with me. Which makes sense, because these narratives are really the ultimate expressions of our alienation from each other, fantasies of solitary dominion and personal rewilding that reveal far more about the social structure of life under contemporary capitalism than they do about what its collapse would really be like.

I was thinking about the all-American ideology Prepper embodies Thursday afternoon, when I saw the foreman from the door factory painting over the fresh revolutionary utopian slogan that had been painted on the outside of their shop floor, and it got me wondering what better possibilities could actually be lurking on the other side of the zero day events the magazine wants to keep just outside the limits of the real.

Sous les pavés, le fôret

With the dog days of August settling in, I am going to give this newsletter a few weeks off, and return in September. I have a big overdue fiction project to work on, some family vacation to take, and projects like this benefit from occasional intermissions. While I’m away, I encourage you to check out other sites like the urban foraging and fishing feed of my friend Matthew Bey, the avian behavior feed of Hillary Hankey, and Gentle Decline, the climate newsletter of Drew Shiel, which is the closest thing I have found thus far to the Bob Ross version of Prepper.

Enjoy your summer holidays, and see you on the other side of Labor Day.

I really look forward to your intelligent and thoughtful posts.

Thank you. They are terrific.

I keep remembering how I used to remind my anthro students that no civilization in the history of humankind has lasted forever. Is it weird that knowing the end is normal makes me feel better? All the best with the book work...and enjoy your holiday.