Parakeets of the Apocalypse

We had a consulting arborist out yesterday, which I decided after meeting him is high on my list of sweet jobs: walk around, look at trees and comment on their health and beauty, without ever having to climb them or cut them. He had just enough wizard about him to really bring out the art in it, dropping implications of immortality and conjuring visions of what this or that tree will look like in fifty or a hundred years.

The tree whose health we really needed an opinion on was the big old mesquite outside the trailer where I work. My wife is designing a small guest house and studio for our growing family, and the current plan is to site it near to and in conversation with this tree. Mesquites are tough trees with thorns that can puncture a car tire (this one punctured my fat bike tire last weekend) and the hardiness to endure the kind of intense climate conditions we have here. They are also gnarly, and a mature one like this, which the arborist estimated is about seventy years old, gets extra gnarly—especially when it’s survived years of illegal dumping, installation and removal of a petroleum pipeline, new home construction, and the loss of some big branches. To our delight, the prognosis was good.

I had inspected the tree earlier in the week, when a Zoom call I was on was interrupted multiple times by tapping on the door. When I finally got up to check, I realized it was just a group of parakeets up in the mesquite, pigging out on ripe seedpods and casting the remains onto the aluminum hull of the Airstream. Not unlike the guys from the door factory next door who have a curbside happy hour every Friday from five til sundown and toss their empties to the curb (unlike the parakeets, they come to collect them on Monday).

Pets gone wild

The monk parakeets are an invasive species, but they are a peculiarly charismatic one, and I love this season when the old mesquite brings them for a monthlong picnic above my head. Sometimes I find an empty peanut shell in the yard or on the street that has been left by one of them, and I wonder if they live at some circus where those come from. They announce themselves loudly whenever they are headed your way. They can get away with it, having found a place where none of their hometown predators exist.

The parakeets are one of the first birds I really started paying attention to after moving to Austin in the late 90s. For a while I lived in a rental next to the University of Texas intramural fields, and in the mornings my son and I would explore the zone around there. Waller Creek runs between the main playing fields and the archery range, and in the spring it would fill with tadpoles. But along the mowed and groomed perimeter were the tall lightposts on which the parakeets would build their nests—condominiums of mud and straw made by one of the only species of birds that lives in multifamily shelters. In their native Argentina, nests have been found with more than 200 familial chambers, weighing hundreds of pounds. The USDA says they “can be very annoying to homeowners living near a colony.” But for a nerd from Iowa, their tropical green colors and raucous jungle chatter were just the right kind of exotic, and the story of how they got here only added to the romance.

The lore is that a crate full of monk parakeets smuggled from their native habitat in northern Argentina broke open on the tarmac of JFK airport in 1967, releasing the birds into the edgelands of the outer boroughs. They proved adept adapters, and in the years since have colonized most of the American coast from Connecticut to the Gulf of Mexico. They love to use man-made structures as the base for their big nests, especially power poles and electrical substations. There’s a big colony on the cell phone tower behind the 7-Eleven down the street, next to a paved creek, and every time I run or walk by there they are out doing their thing (the picture above is from the 7-Eleven parking lot). Fully naturalized to this Anthropocene habitat, they remind us that we are an invasive species too.

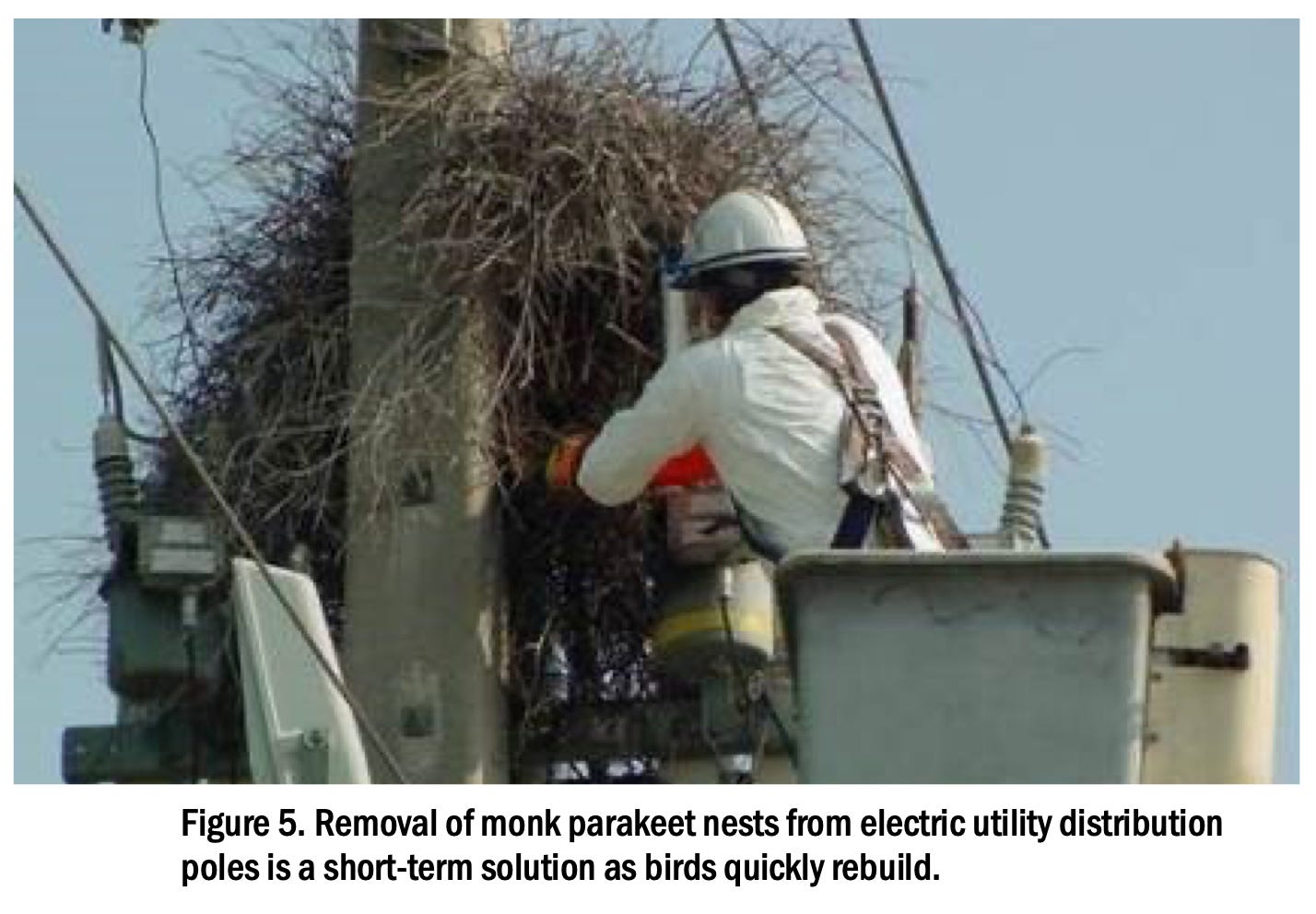

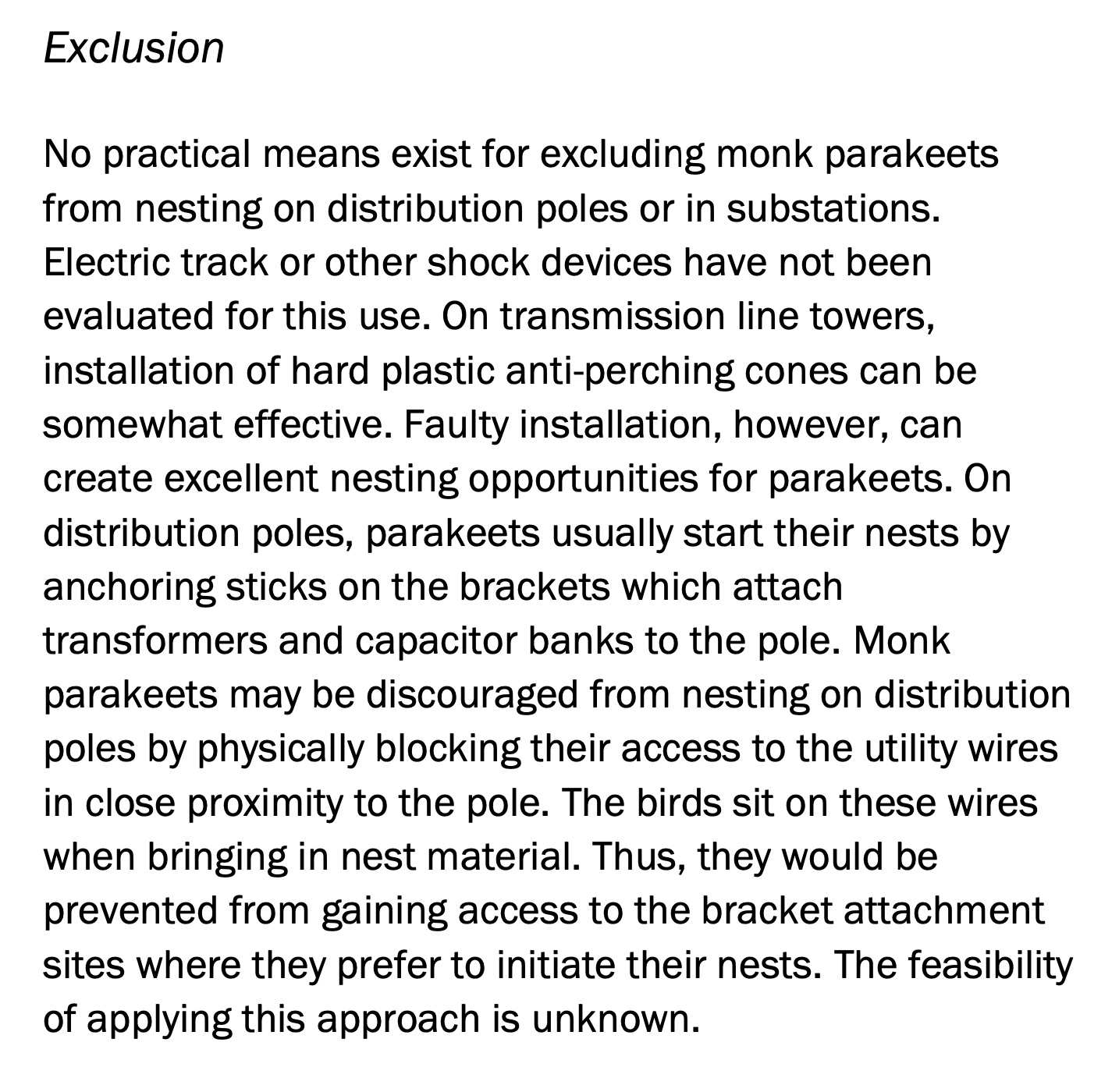

There is an entire literature out there on how to manage the parakeets’ colonization of our power and telecommunications infrastructure, and it’s kind of hilarious in its clinical documentation of Sisyphean futility. The parakeets are basically unstoppable, in part because they are so perfectly adapted to our own colonization of the landscape. The USDA’s white paper on the subject, part of its Wildlife Damage Management Technical Series, is an accidental masterpiece of invisible literature:

The paper is full of interesting details, like the birds’ “distinct preference for certain types of transmission tower designs” (H-Frame concrete towers more than H-frame tubular towers, because of the flat surfaces). Apparently the only effective way to control their population that the wildlife management types have come up with is by feeding them the oral contraceptive diazacon, but even that only cuts back the number of eggs they hatch. There is also a rather grim discussion of euthanasia, noting that the American Veterinary Medical Association approves the use of carbon dioxide gas and “cervical dislocation, if performed by ‘well-trained personnel who are regularly monitored to ensure proficiency.’” A disturbing training session to imagine.

The section on the birds’ legal status reminds you that, as an invasive species, they are unprotected. And that while they can no longer be legally imported, they are frequently bred in captivity and remain “a popular cage bird.” But what really gives them such allure to me is as a symbol of ornery freedom, the pet that liberated itself and took over our habitat, only to somehow fit in.

Some notes towards a post-apocalyptic aesthetic

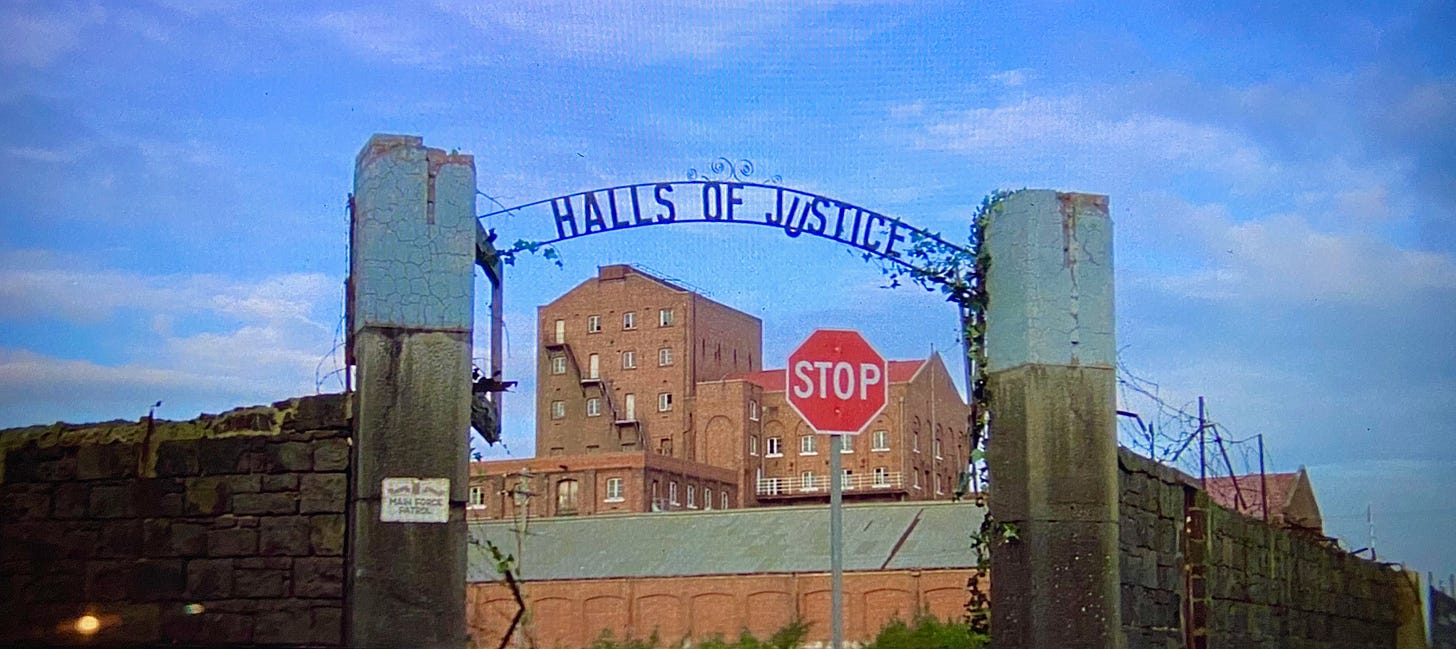

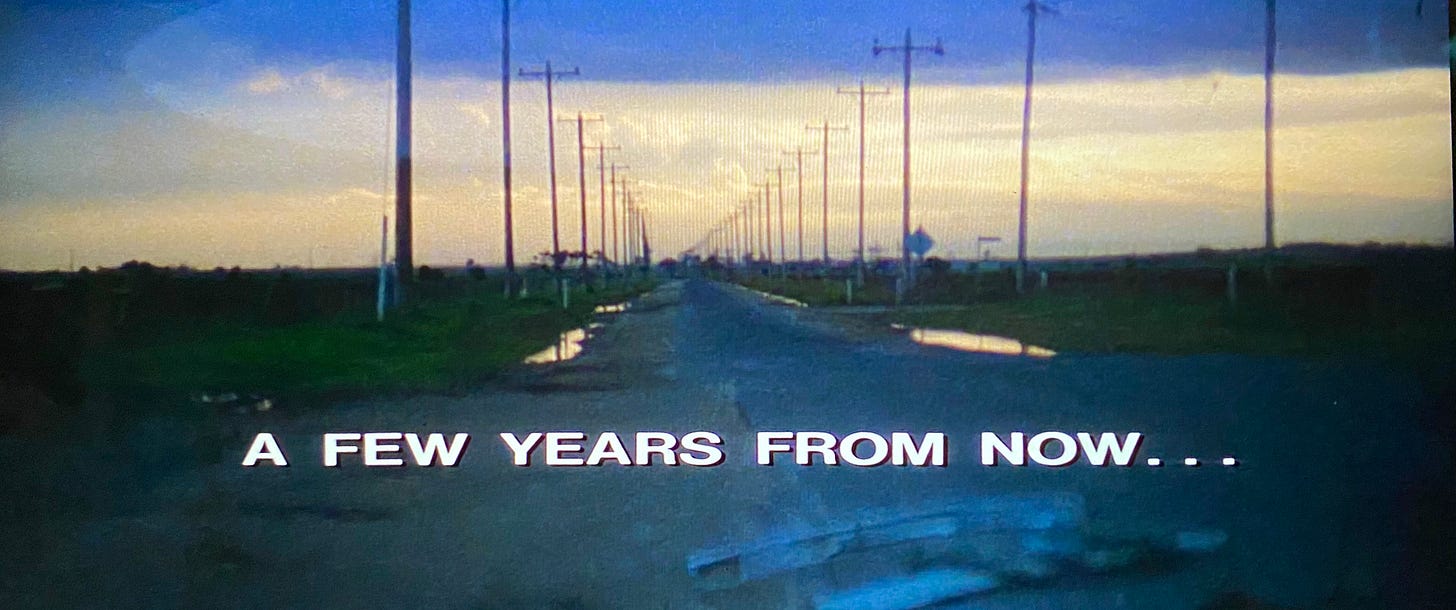

During quarantine I have been having a weekly Zoom call with some nerd buddies in which we discuss a film on the prior week’s call—usually something streaming on the Criterion Channel. This week’s selection was one I had already recently seen (Lizzie Borden’s revolutionary and freshly relevant Born in Flames), so I launched another newly added movie I had not seen since shortly after its release: Mad Max, the original from 1979, made by director George Miller when he was still working as an emergency room physician.

I expected it to suck as much as I remembered it. And when it grabbed me with how good it was, I realized the reason it had sucked was that the original U.S. distributor had the stupid idea to dub all the dialogue with American-accented voiceovers, giving it the weird feel of a Godzilla movie without the monsters. The other problem was that I had only ever seen it on VHS. With a clean digital print and the original Australian English restored, it’s an intense film, especially the opening—CGI-free high-octane Ozploitation that turns DIY pulp fiction into kinetic art.

I remember being disappointed upon my original viewing at its failure to live up to the “warriors of the wasteland” setting of its better-known sequels. But watching it now, its use of real-world locations from the outskirts of Melbourne feels weirdly grounded in our contemporary moment. The settings look a lot like the Austin edgelands where we live, or the outskirts of Houston—lots of industrial facilities and warehouses amid big tracts of undeveloped land, green but starting to dry out. Not post-apocalyptic, but a window into a society collapsing so slowly that its inhabitants don’t see what’s coming.

I’ve also been reading the galley this week for a new post-apocalyptic novel, Strange Labor by Rob Penner, one of the most beautiful and smartest books I have encountered in the sub-genre. It’s the story of a woman traversing an America in which huge portions of the population have left the cities to construct gigantic labyrinthine earthworks of enigmatic purpose and meaning. So when baby and I were out for a jog Friday morning on a trail that paralleled a tollway construction site busy with big digger machines moving dirt, and then saw a man pedal out from his camp in the woods behind the dairy plant wearing a full face covering, dressed in sun-protectant outdoor gear and pulling a rugged DIY bike trailer, I felt a little bit like the lines between science fiction and reality were slipping.

I’ve been attracted to the post-apocalyptic aesthetic since I was a kid. I used to play a role playing game called Gamma World, in which I would map the future ruins of Des Moines on big sheets of hex paper. But as the fear of nuclear annihilation that informed the stories of my youth waned, I began to see those scenes of cities in ruin through a different prism: as maybe not the end of the world, but the beginning of something better, maybe even a return to Eden. Consider the final reel of 1977’s Logan’s Run, in which Michael York and Jenny Agutter escape from their domed utopia—shot in a Dallas mall—and discover the vine-covered remains of Washington. The characters realize they have discovered real life. And as the wonder subsides, the viewer (at least this one) realizes that the green swamp that’s depicted is much more beautiful and healthy than the real D.C. (where I lived for many years).

This half-baked idea of celebrating the post-apocalyptic aesthetic informed the design of our home: a house meant to look like a bunker being retaken by nature. And every year, we dial that factor up, as the cross vine reaches further down our windows, the tall grasses get taller, and the house gets harder to see even when you are standing right in front of it. An architecture in which building bows to landscape.

The restoration of wild nature inside the city has an intrinsic romance to it. The idea of living like some forager of the post-apocalyptic wasteland not so much, especially when you are reminded there are people already living like that in the margins of your own neighborhood. But I think the persistent allure of those kinds of stories has something to do with our sense that they tell truths about our nature, about a life without the security of accumulated surpluses of grain and water (and the mediums of exchange they engender), imagining a liberation from the kinds of lives we must lead to keep the machines that generate those surpluses running. Post-apocalyptic stories are climate fables, even when they don’t claim to be—stories that express our understanding that our dominance of the planetary environment is out of balance, but we are incapable of correcting our trajectory. We’ll still be fighting over the last drops of oil in the ground when there’s no place left to go.

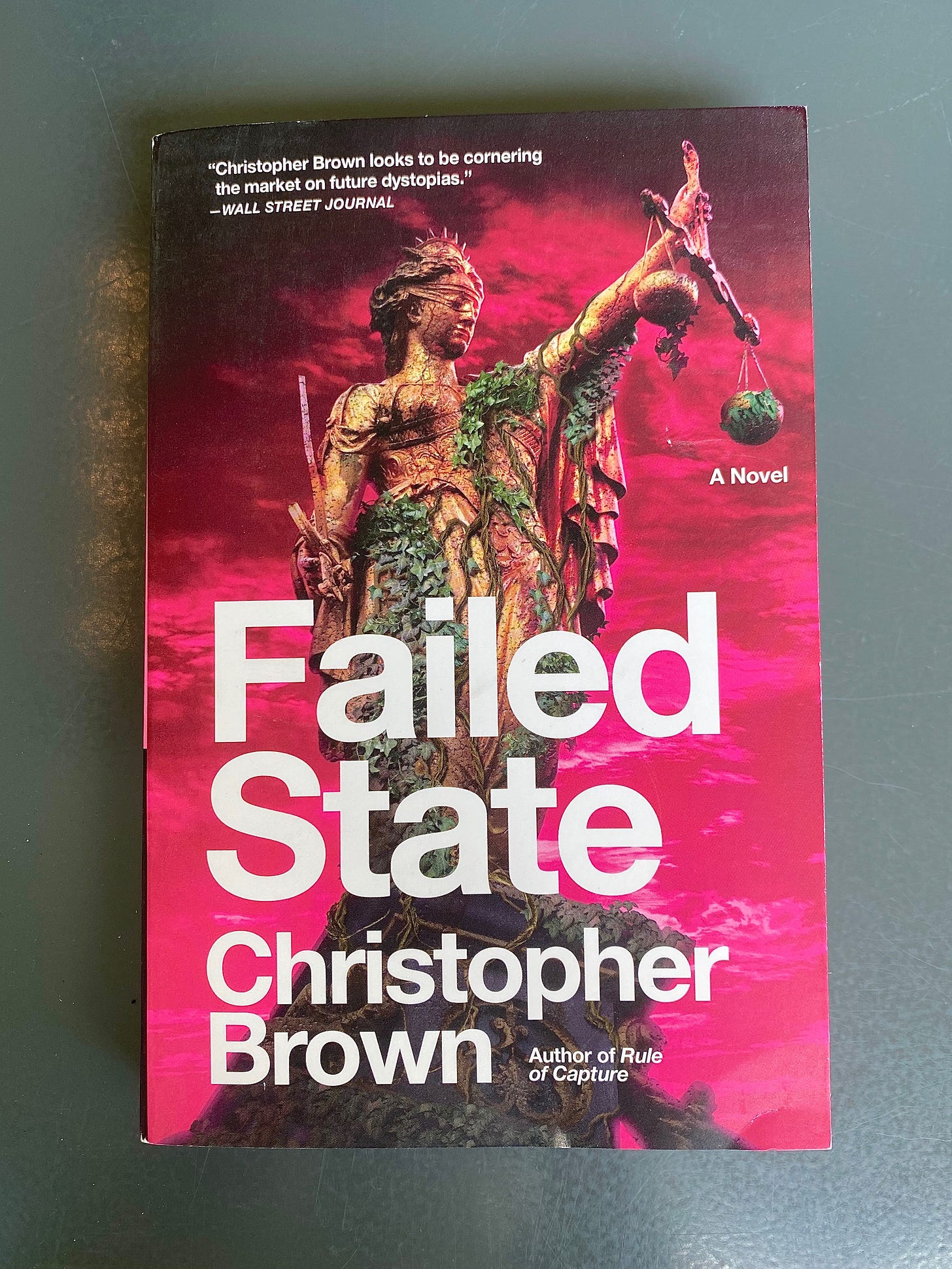

In my new book out Tuesday, I try to play with this idea of the post-apocalypse as being not so much dystopia as the counterintuitive path to utopia. It’s set largely in a hurricane-ravaged New Orleans whose inhabitants have declared an autonomous zone and begun to beta-test a greener future, radically rewilding the city. It’s also a lawyer story, which gave cover designer Owen Corrigan of HarperCollins quite a challenge—convey this idea of the collapse of civilization being a new dawn, while at the same time cueing that it’s a legal thriller. I finally got my hands on my first print copy Friday, in this year of digital galleys and bookstore closures, and his amazing design looks even better in person:

Wednesday night August 12 at 7 pm CDT, Austin’s BookPeople will be hosting a virtual launch event at which I will be in conversation with my friend and colleague the author and activist Cory Doctorow, so please join us if you are interested in talking about how to build more optimistic futures in fiction and in real life. BookPeople is also taking preorders for the book, which travels through territory very similar to this newsletter. If you prefer the electronic or audio version, details and links for those are available at my main site.

Have a wonderful week.

Further reading (and viewing)

Audubon: “The Monk Parakeet: A Jailbird Who Made Good,” by Nicholas Lund

USDA: Monk Parakeets — Wildlife Damage Management Technical Series (PDF)

Mad Max (1979) — streaming now at the Criterion Channel (also on Netflix)

Strange Labor, by Robert G. Penner, forthcoming from Radiant Press (available for preorder)

Born in Flames (1983) — Lizzie Borden’s documentary-style vision of feminist revolution, streaming now on the Criterion Channel