Onward through the Nebelmeer

This week started off foggy. Monday looked more like our winter mornings, when cold nights are dialing up into sunny days, and the river finds its inner fog machine. Thick fog is a little creepier in spring, and clammier, but the river and woods soaked up the days of rain that preceded it, and by mid-week you could hear the amphibian life croaking its return all through the woods and right up to the house.

The weather witchers say this may be the last rain we see for a while, on account of a pattern they have decided to name La Nada. Picking up the paper on a foggy morning in time of pandemic and reading of a looming atmospheric phenomenon called The Nothing sort of suits the mood of the moment. Especially when you read further, and learn that they use that term because the absence of historical weather patterns means they don’t have a clue what’s coming.

“Onward through the fog” is the slogan of our oldest and most venerated head shop, the one that represents the spirit of 1970s Austin with a cartoon of a happy old hippie dude trucking along in oversized boxers. The wildlife on the river seems to follow that aphorism in its own more lucid way, like the osprey we found perched right there at the trailhead Monday morning, in a tree much lower and closer to the water than its usual vantage. A blue heron was in the nearby shallows, working his way through the big bivalves that cluster in the freshwater shoals. The ducks were were chilling like little brown specters, just far enough into the fog that they seemed to be dissolving in and out from some other realm.

Five years ago, an anonymous artist I later located and became Internet pals with built a work of land art in the woods near here, out of broken hackberry and loops of thick mustang vine. It was the gateway he made to represent his leaving, I learned, and he called it the Portal. That was exactly what it looked like, the first time I came upon it, and that’s exactly how these woods work. Especially when the fog rolls in.

Fog can’t shut down the human machine as effectively as it once did, now that we have electronic eyes to see through it. But it slows things, and brings a stillness. It’s a stillness that’s different than the quiet that follows a blizzard, or a big storm. More mysterious. And when it blankets the river, a place where reality already tends to bend, it alters your perception of time.

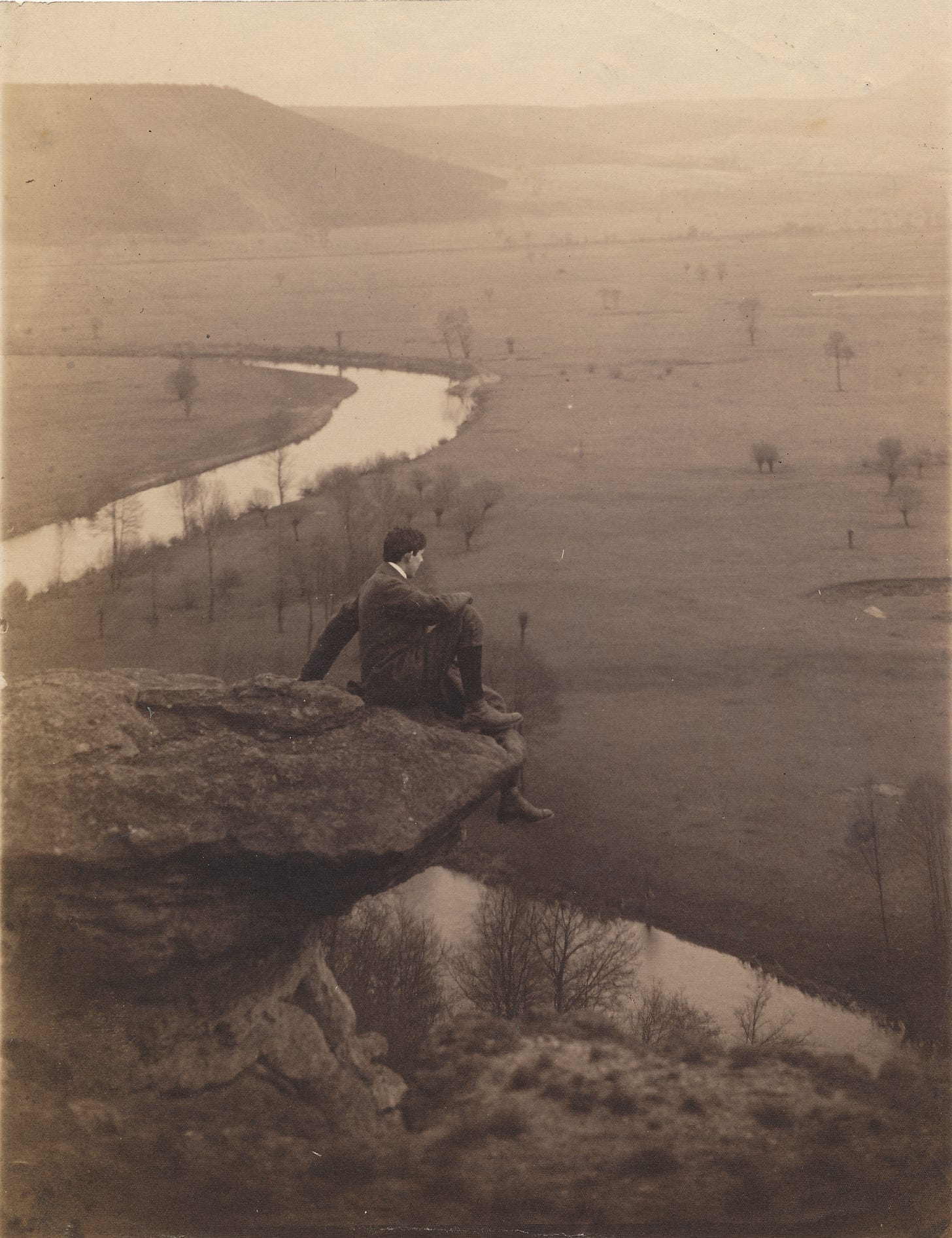

I have a natural proclivity for wandering off into the fog, when life will let me. At the same time, I am wary of its romantic allure. I come from a long line of landscape-loving Germans, and I can see where their mysticization of the land got them, when they sought out the mythic past they saw hidden in the mountain mist. There’s a picture I have on my office wall of my grandfather sometime right after World War One, getting his Caspar David Friedrich on in some riverine Prussian Landschaft. It’s a useful reminder to keep around, of both the wonders and moral hazards you can encounter through that portal.

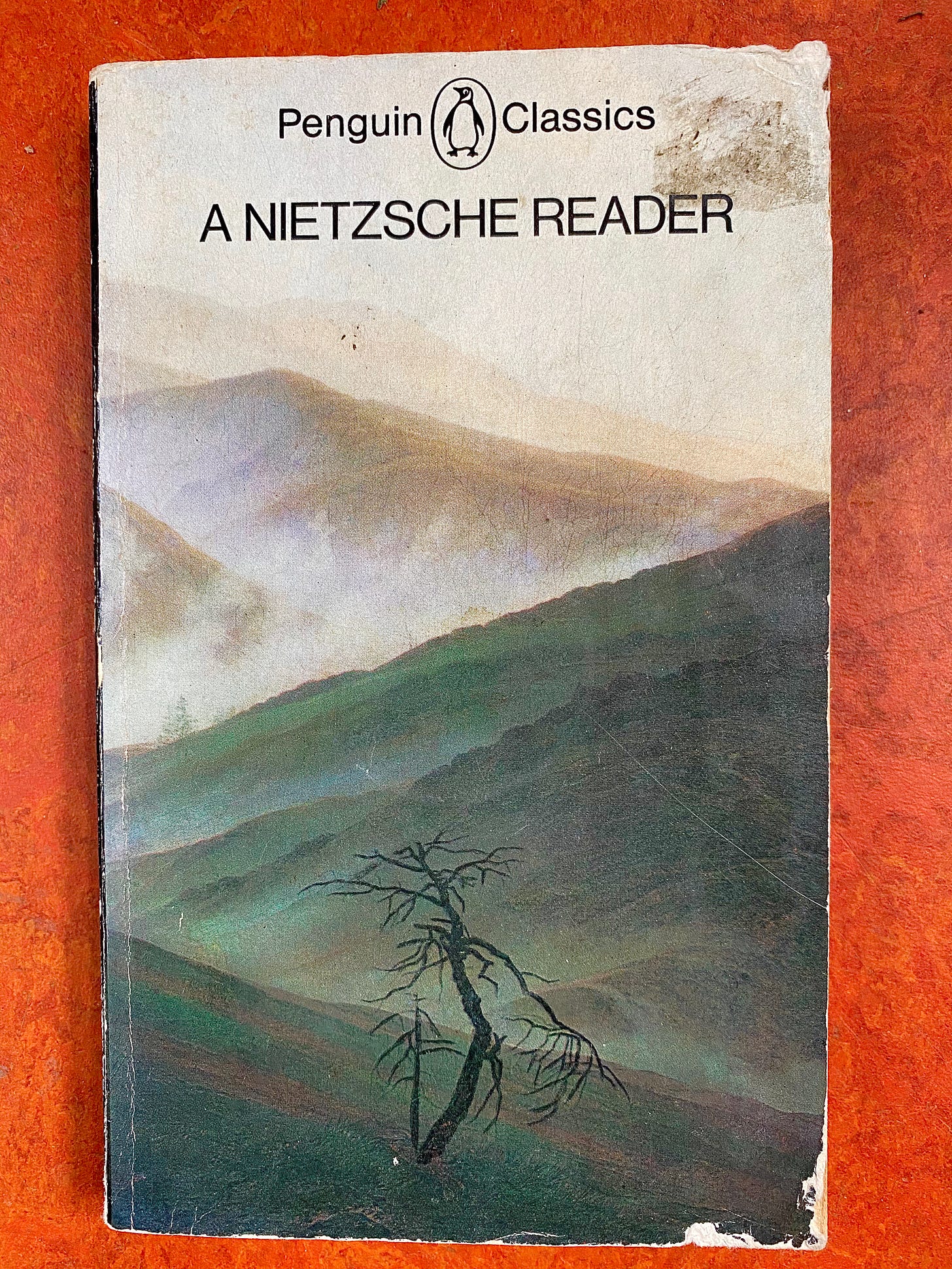

Opa’s ancestors were foresters, according to family lore, tending the wild preserves of the rich. People who worked alone in the woods, navigating its surprises. That paradigmatic image of the lone figure staring out into the great unknown persists in hundreds of movie posters and ten-thousand eco-Instagrams, and it’s one I can relate to. It touts a different sort of strength than the Texans who stencil stag skulls on their pickup windows. The pose of the wanderer is a kind of existential hunter, ready to navigate the uncertainty of what’s out there. That Nietzschian take on interdimensional self-reliance has its place, especially in times of fogged-up futures like this one. But I think it only works coupled with a strong sense of community, no matter what the philosopher said.

Wednesday morning the pre-dawn sky was dry and clear. The suspension of commerce had even darkened the heavens in a small but perceptible way, letting more stars in through the dome. And when I looked up in the east, I saw three unusually bright objects just above the woods behind the factories, radiating an energy that was almost tangible, each with a distinct color you could see with the naked eye. This celestial trio, I learned that afternoon from an astronomer friend, was Saturn, Mars, and Jupiter. Pluto was in there too, between Mars and Jupiter, too dim to see in town. And when I considered what those four gods embody, I couldn't help but wonder what their appearance portends. Not that I put much stock in astrology.

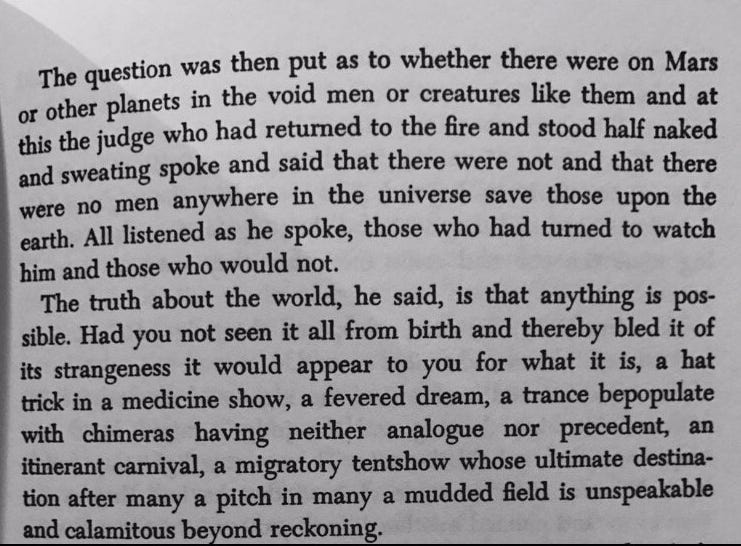

Later in the week, I found myself remembering the crazy passage late in Blood Meridian, when the Judge—another apocalyptic naturalist, one who keeps a nature journal during his gang’s murderous campaign through the borderlands—turns his own eye to the sky and reports the truths he divines.

Thursday afternoon I went on an urban trail run that traversed highway cloverleafs and wildlife preserves. The crews building the new tollway and bridge were sheltered in place, evidently, so I was able to run right up the little mountain of dirt they have built where the old onramp used to be, near the deserted traffic island I wrote about a couple of weeks ago. As I came down the other side, I noticed fresh animal tracks there, deep in the construction zone—a big deer and a small coyote, maybe the one tracking the other. I wondered if the sudden stillness of the city has given them license to venture further into our realm. Even as the path they were on will soon be an impassable concrete corridor. Assuming the building doesn’t stop.

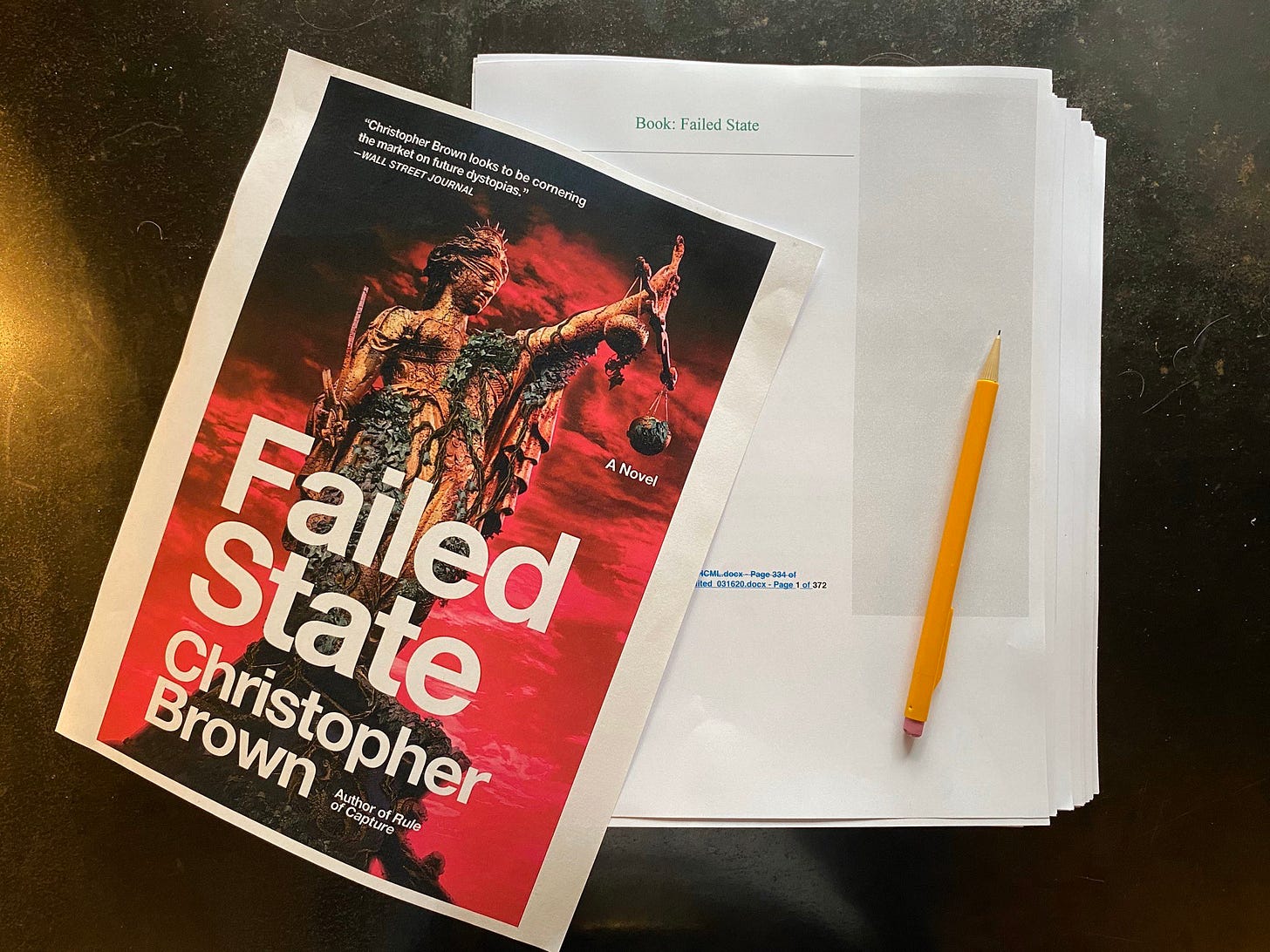

I spent most of my week inside, busy with work. I got to read the city government’s shelter in place order for my clients, and see how much ambiguity it creates around what constitutes an “Essential Business.” I also worked my way through the copy editor’s mark-up of the book I have scheduled for publication this summer. Writing dystopian fiction feels like a frivolous undertaking when true dystopia takes over real life with disaster movie immediacy. That the book has utopian aspirations helps, telling the story of people trying to cobble together a better tomorrow in the aftermath of a nation-breaking crisis that leads to mass joblessness and food insecurity. But writing science fiction gets tricky when the idea of the future makes the kinds of evasive maneuvers it has been making lately—even in the six short weeks between turning the manuscript in and moving to production.

A main purpose of narrative exercises like that, at least for me, is to create liberated territory for the imagination of how else life could be. It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than a real change in the political system, or what comes after capitalism, as many smarter people have said in various permutations. But when those kinds of changes happen IRL, as the human anthill is frozen by a virus some say crossed the species barrier through the habitat destruction of urban sprawl, and the strengths and weaknesses of our existing system are exposed in high relief, the opportunities for applied science fiction are manifest. Maybe the way we have been living isn’t the only way we could.

The immediate task is to take care of our neighbors, and to remedy the damage the last two weeks have unleashed here, and that are only just unfolding. But as we experience what life feels like unleashed from the cubicle treadmill, and from the illusory addictions of consumerism, it’s hard to imagine going right back to the way it was before. And as you witness the stillness of which the metropolis is capable, it’s a lot easier to imagine a world in which the animals hiding just outside of our view are able to share the city with us more openly. Not unlike these black-bellied whistling ducks I have been seeing all week, chattering in the trees and power poles around the industrial lots of East Austin, moving into territory far from the sanctuary of the river where we used to see them exclusively during the nadir of the Great Recession. Maybe they can see the future more clearly than we can.

For more land art of the amazing Cameron Krow, now back in his native New Mexico, check out his Instagram.

Several of you expressed appreciation from my recommendation last week of The Great Leveler by Walter Scheidel, a study of how pandemics and other violent disruptions of human societies impact wealth and inequality. For the deep origins of that inequality, and most of our other problems, another excellent read is James Scott’s Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, which postulates a very different take on the agricultural revolution and the ways in which humanity made nature its servant.

And if you are looking for more page-turning quarantine reading, I was pleasantly surprised to see this recommendation last weekend from the author of the brilliant Networks of New York: An Illustrated Field Guide to Urban Internet Infrastructure and The Training Commission, fwiw:

Have a safe week, and get outside in the fog if you can.