Night raptors and urban explorers

Monday morning when I stepped out of my trailer into the pre-dawn dark, a huge raptor flew past my head, maybe a few feet away, in the direction of the woods behind the door factory next door. This is the season for nocturnal avian hunters, and I’d been having similar such flybys all month long. The nighthawks are out in big numbers this year, often flying lower, and the bats are out, too, sonar-dodging my head sometimes as I shuffle up out of our buried house and onto the path, though their population seems to have been decimated by the big freeze.

All birds change into different creatures when they take flight. The night birds take it up a level, becoming part shadow. When the specter of what you assume must be a big barred owl flies by so close to your head that you can feel the wingbeats, your body reacts with animal instinct faster than your mind can assemble the inputs into a coherent picture. An India ink apparition, the wingtip blades and liquid pools of a creature that swims through the air the way a shark moves through water. When you remember it, you have some idea what those shadows must be like for the creatures of the field.

Austin has been getting its Houston on since May, with daily rains, especially at night. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen it this green in our feral yard, and I keep seeing plants I have never seen before, or maybe just never noticed before, some of them so intrinsically beautiful they reflexively convince you they must be of this place, others structurally odd things that look almost artificial. There’s a vine with a leaf like ragweed that has been growing along the chain link of our front gate, along the same spot where the delicate native snapdragon has somehow maintained a home, and it bloomed this week with an elaborately structured purple and white flower that looks like it was invented by the Star Trek art department for some backlot alien planet. In a few days the mind parasites will have taken control.

The rain and the crepuscular air hunters go together. The night storms begin to clear before the sun starts to telegraph its arrival, bringing out the flying bugs who have been breeding in the replenished waters of the urban woods, and the little birds and bats who have learned to fly in the zig-zag patterns of creatures much smaller than them fill the air for their balletic pig-out.

Sunday morning we witnessed just how quickly the cliff swallows are colonizing the underside of the four-decked, sixteen-lane new tollway overpass. You can almost reach them from the old 1930s bridge that is officially closed but unofficially converted into the coolest pedestrian walkway in town. And when they fill the early morning skies, as the post-pandemic traffic begins to fill the roads, you can’t help but marvel at how much life energy can be generated from the slivers of wild nature allowed to exist between factories and freeways.

At night, the tropical weather fills the woods above the urban river with amphibian song. When we first moved here more than a decade ago, living in a rental cottage next door while we tried to figure out how to get our crazy house built in the brownfield, we would sit outside on the porch and just soak up that chorus of frogsong that filled the dark, occasionally interrupted by the skronk of a horny heron. The only thing visible when you looked out there was the slow motion woodland sparkle of fireflies. It gave you a feeling of how many other beings were living in the space around you, singing in languages you could enjoy but not understand.

When I heard the frogs this week, a sound that had seemed scarcer in recent years, it brought joy. I remarked at how exactly their song was replicated by the beautiful toy our daughter-in-law had brought our toddler daughter from Korea—a little frog carved by monks from some light wood, with a little stick you can pull out from between its jaws and drag across the ridges of its back to make that beautiful slow roll of wetland life. It was like we had summoned them with this magic object that could speak their tongue. But then later in the week as I paid more attention, I realized how few of them their really were. Maybe even just two. And I wondered whether our own presence in this space might have helped displace their grandparents.

When my son was in grade school, we lived near a little urban creek that ran between the university intramural fields and the state police obstacle course, which is now an apartment complex. And one spring day exploring back in there, we found tadpoles in that skanky water. He had done a school science project where we went looking for the source of that creek, springs that used to run at what is now the intersection of two freeways, and we marveled that these little amphibians could thrive in the runoff of asphalt sweat and fertilizer.

As I stood there this week in the dark listening to the call and response of the frogs, I watched the slow motion semaphores of the fireflies at the edge of the woods. And got to remembering how many more fireflies summer would bring when I was a kid. Last weekend someone had shared with me an op-ed by the science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson reminding me of the horrific statistic that only 3% of the Earth’s animal biomass is wild—the other 97% is humans and our domesticated animals. The piece was evangelizing the idea of concentrating the human population in megacities complete with vertical farms while converting huge swaths of the countryside back into wilderness, but it had me wondering whether that trajectory of dominion could be corrected by rewilding the city itself.

As I sat down to write these notes, I dug out my copy of Charles M. Bogert’s 1958 record Sounds of North American Frogs to see if I could identify the critters singing love songs behind our house. When we first moved to Austin in the late 90s, one of the local public radio DJs would play outtakes from that album, which had just been re-released by Smithsonian Folkways. The thing the DJ loved about it was the heavy regional accent of the herpetologist drawling over the scientific and common names of the creatures, and he was right, but the field recordings are even better. I downloaded the CD onto my computer back when that was something one did, and it ended up on my phone, and the tracks always show up more than they should in my shuffles. But apparently I haven’t been paying them close enough attention all these years.

Turns out this week’s backyard chorales aren’t frog songs at all, but the mating calls of Gulf Coast Toads. Apparently one of the only species of toads native to this region to have thrived despite the invasion of fire ants, who swarm the same water sources where the toads breed, and devour the toadlets as they emerge. The Gulf Coast Toads breed later than their cousins, and are hardy adapters to urban environments, finding all they need habitat-wise in ditches and storm sewers. They may not be the evidence of wildlands restoration I had romantically presumed, and they may not be as beautiful to the eye, but I look forward to hearing them share our space all summer long.

Parable of the Skatepunk

I’ve written here before about my half-baked theory that the art directed aesthetic of post-apocalyptic cinema, with its ruined freeways, overgrown shopping malls, and drowned downtowns, is not, as conventional wisdom suggest, a warning of the nightmare hellscape our sins will consign us to, but a vision of the world we secretly yearn for. So it was with a head full of such ideas that I digested this sponsored post the Instabots served up to me Wednesday morning:

“The Carry-On Suit, featherweight peached cotton twill with a little stretch,” perfect for that post-pandemic business trip or post-apocalyptic skateboard forage.

It was hilarious how well the algorithm had me nailed, at the eccentric nexus of urban exploration, business casual, and dystopia. The image looked to me like some Abbot Kinney art director’s take on Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, as channeled through the minds of white dudes whose paradise is a landscape of empty swimming pools and open freeways. But as I dug further, I realized that wasn’t what they were going for at all. It was an accidental byproduct of their sidewalk surfer bro aesthetic and their shameless racial appropriation. The background location is not some imaginary end of the world, but the run-down world we live in. Maybe the post-apocalyptic aesthetic is now just a flavor of realism, as we find the Romantic in our own national decline.

The climbers

Elsewhere on urban exploration Instagram, Thursday’s New York Times carried a fascinating piece on Isaac “Drift” Wright, an Army Special Forces veteran who developed a unique method to deal with his PTSD—illegally climbing massive urban structures and making beautiful photographic art from his adventures, and becoming the target of police intelligence operations across a half-dozen cities, leading to his arrest and incarceration.

I’ve illegally climbed a few medium-sized buildings myself over the years, including a lot of churches, synagogues, and schools when I was younger, and as an adult I’ve jumped plenty of fences seeking urban nature as chronicled in this newsletter. In the oughts I became fascinated with the more extreme skyscraper and bridge climbs chronicled in places like Jinx Magazine. The Jinx guys even wrote a book about it, Invisible Frontier: Exploring the Tunnels, Ruins, and Rooftops of Hidden New York, which I still have (one of them later moved to Austin, where he now runs a creative studio). So while the Times piece was sympathetic, Wright’s situation seemed much more deeply unjust to me than the story conveyed—how this Black veteran was turned into a public enemy for doing something white hipsters have been doing for decades. Maybe his real crime was that he did it so much better. Another reminder that the outdoors is often more racist than the indoors, no matter how high you climb to get away from it.

From the urban frog stream

For more on the Gulf Coast Toad and its urban survival strategies, check out this great post at UT Austin’s Biodiversity Blog.

If you want to hear the songs of North American frogs while you roam the city or sit at your computer, Smithsonian Folkways has all the tracks from Charles Bogert’s 1958 disc available for listen on their site, and you can directly download the record for a reasonable price. Bogert rated a brief obit in the Times when he died in 1992, from which I learned there’s an endangered species of venomous Guatemalan lizard named after him, and now I wish I could hear him drawl the vowels of Heloderma charlesbogerti.

And over at Bloomberg Green, Kim Stanley Robinson on Cities as a Climate Survival Mechanism.

Phasmids in love

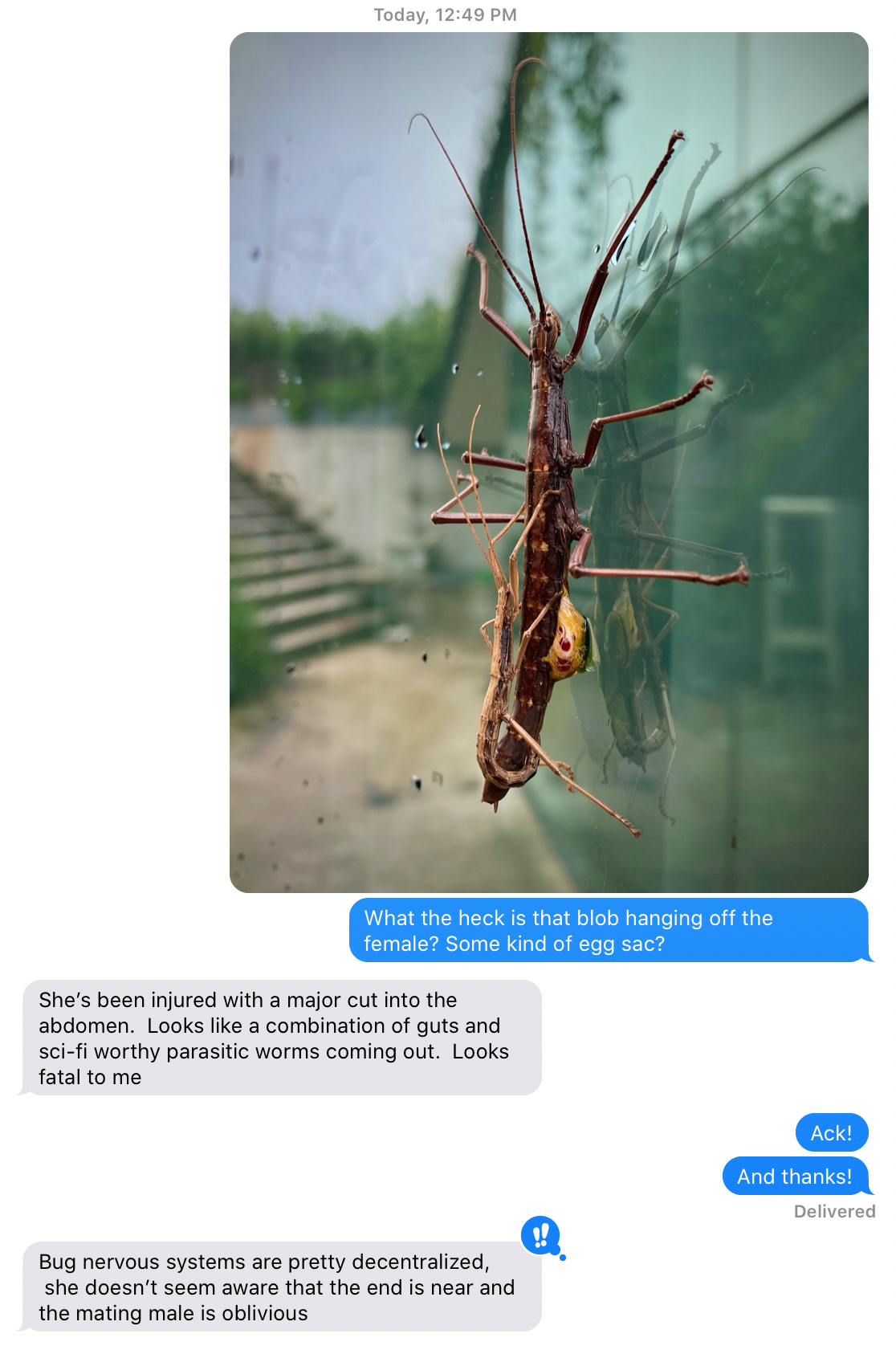

The amphibians aren’t the only ones in a family way as summer begins here, as evidenced by the Texas walking sticks I found copulating on our bedroom window Saturday morning after a break in the rain. We see these little monsters getting at it all the time, partly because they often remain in that position for days, for reasons of genetic competition among the diminutive males. There was something unique about Saturday’s sighting though, causing me to reach out to my entomologist neighbor, resulting in a text thread that made me think we need to get Tom to narrate his own album of field recordings:

Aren’t they always?

Have a great week, and keep it together.