Mr. Prolong versus the Swamp Thing

We got a good long rain Saturday, just when we were starting to think it might never rain again. That it would just get a little hotter every day, on a week that began with reports of fire tornadoes in the west. It’s only been a month since the last rain here, but it feels longer, and when I saw the flashes of distant lighting in the night, I dismissed the possibility, convincing myself it was man-made. The summers have gotten more humid in the two decades I have lived here, and when the triple-digit August sun shines on you in the afternoon you feel like it is steaming the last drops of moisture out of the ground. The trees look like they are barely hanging in there, the goldenrod wilts before it blooms, and the grasses give up and say see ya next year, suckers.

But it was real. At five a.m. it was raining enough that I needed to put on a hat to head out to the trailer where I work, and as soon as I sat down at my desk it was coming down hard. The sound of real rain on the aluminum hull of the Airstream was sweet, even if it meant I had to worry about the leaks between the panels and water seeping out onto my books. Straightening up my office the other day I found one paperback that had gotten thoroughly soaked earlier in the summer, before I could even read it—a nice old Penguin I picked up right before the pandemic of Sallust’s account of the war against Jugurtha, King of Numidia, whoever he was. At least it washed out most of the left-handed Bic pen annotations the prior owner scrawled on the preface before giving up.

The Maximilian sunflowers don’t seem to mind the summer heat, with plenty of late bloomers turning that solar energy into new life, some clearing twelve feet above the other plants of the prairie. And the native vines all seem to thrive in these conditions—the thick mustang vine that turns the floodplain into a gothic forest and the trumpet-flowered vines that grow from our roof and cover the fences of the old industrial lots nearby. I’ve been appreciating the Drummond’s Clematis in particular this month, the vine that grows these crazy feathery plumes that earn it the name “Old Man’s Beard.” Clematis drummondi is a plant that thrives in the spots we ignore, like one particularly unattended corner of our yard where it grows thick on the scrubby little trees, or the barbed wire perimeter of the truck repair shop around the corner where I took my Land Cruiser this week.

Our fuzzy Clematis was entered into the Western taxonomy by a Scottish naturalist named Thomas Drummond who explored these parts in 1830 and collected specimens for the enjoyment of fellow nature nerds across the Atlantic. It probably wasn’t as hot the summer he came through. There’s a line in the insane settler memoir Indian Depredations in Texas when the author John Wesley Wilbarger, writing about the long night his brother spent after being scalped and left for dead, naked in the swamp as the insects sampled the open wound on his head, remarks: “Those who have ever spent a summer in Austin know that in that climate the nights in summer are always cool, and before daybreak some covering is needed for comfort.” You read that now, and you wonder what changed.

At sunup the rain had slowed, and I took the dogs out for a walk in it. The cottonwoods were soaking in the runoff from the storm drains, and the river was already full. When we came up out of the woods onto the freshly mowed field behind the dairy plant, there were a dozen young deer there foraging in the opening, no doubt figuring the predators were all sheltered. As they scattered across the little plain for the safety of the treeline, for a brief instant you could imagine what it was like back when the Wilbargers brought the first real estate scouts out here, to make way for the eternal hum of the refrigerated trucks idling on the other side of the fence, stenciled with their cute trademarked cartoons of the mammals who live to feed us.

Even on the rainy days, you need to watch what you step on when you walk in the woods along the river in late summer. And the things you see under your feet give other clues as to why it’s so damn hot.

Anthropocene Easter eggs

Last weekend we took baby for a morning walk at Circle Acres. Circle Acres is a former landfill site on the other side of the river from us where Ecology Action of Texas, the state’s oldest environmental non-profit (it celebrated its 50th anniversary last year, and I serve on the board of directors), is managing a restoration. It’s a beautiful site, with a little prairie at the base of a bluff and a verdant wetland in a hole that used to be quarried. Water runs from recovered springs on land so profoundly abused that we are not allowed to do controlled burns because there is still so much methane and benzene in the ground.

Circle Acres may be the most extreme example, but this whole area of town is like that. Wherever you go along the urban river, you are likely to find chunks of old buildings and roads dumped from the backs of trucks, often in the same spots where they used to dredge the gravel to make the concrete. Ruins of the twentieth century, slowly returning to the earth. Our lot has so much that we were able to construct a grotto from it, an outdoor fireplace made from curb cuts and concrete stairs, with sewer pipes repurposed as planters and a brick chimney fragment put back to its original use. We finished it just in time for our wedding seven years ago, and the fire burned bright that night.

The floodplain also collects the material that the waters bring from upriver, most of it plastic, and every walk in these woods is an Easter egg hunt as you come upon unlikely artifacts. Sometimes they are fossils, or stone tools of the people we displaced. Pieces of settler pottery, and the garish paisleys of hippies who left behind their clothes. And all the plastic toys kids leave in the yard further upriver.

Earlier this summer my daughter and I found a little figure of the Black Widow that she likes to pull from the outdoor table and play with. There’s a princess chariot I found years before she was born, which she has also discovered, and now stripped of its wheels. And this baby’s arm, which I discovered yesterday finally fragmented into hand, elbow, and shoulder.

We have a big terrarium in our living room filled with a decade’s worth of such objects. A plastic zebra, the jaw of a opossum, a .45 jacket, a raccoon skull, a Camp David cufflink, Superman’s leg, the fossilized remains of a Cretaceous bivalve, the wing of a bird, a parakeet feather, Spiderman’s severed head. The funniest and nastiest one is the empty little spray bottle I dug up in the yard labeled “Mr. Prolong—a topical spray designed to prolong the act of love”—from the days when our quiet little side street at the edge of town was a lover’s lane. The juxtaposition of these objects accretes a beautiful surreality that encodes the essence of this place, even as the planetary accumulation of plastic trash it reflects can make you sad.

When you see how much trash is left after a big flood on the downriver side of a town as big as Austin, you wonder how much we must pollute the places we can’t see. Like the ocean this river pours out into at the coast, and all the other ones. And even as the pre-dawn skies of pandemic summer seem appreciably clearer, but nowhere close to the night skies of your childhood, you wonder about the things we pump into the air, the layers of particulates that trap that August sun and make you feel you’re the one living in a terrarium.

“Self-limiting genes,” indeed

I’ve been binging stories that explore ecological themes, as I begin to work on my own next fiction project. I’m working my way slowly through the original Spanish of Samanta Schweblin’s Distancia de rescate (which translates as “Rescue Distance” but was published in English as Fever Dream), a beautifully-written and cleverly structured novella that evokes horror through conversational allusion and the instinctive knowledge you bring to the text of the impact interventions like spraying crops with pesticides can have on human reproduction. I’m also beginning Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season, an intense and experimental new Mexican novel that ties human violence to a hostile landscape.

This week I watched two great Australian films in this vein, both available for streaming on The Criterion Channel, and both filmed in 1977. Chris Eggleston’s Long Weekend is one I found on a list of ecologically-themed scary movies, about a couple on the rocks who try to save their relationship with a camping trip to a secret beach, only to find their active cluelessness about the impact every little action they take has on the natural world around them will bring about their own ruin. It was much better than I expected, more psychological suspense than horror, beautifully shot, and with just enough restraint in its portrayal of animals. It’s especially remarkable for the way it makes you identify with unsympathetic protagonists. And its use of a mysterious wild bird egg as MacGuffin (pictured above in the hand of Briony Behet as Marcia) is brilliant.

I had seen Peter Weir’s The Last Wave on cable TV back in the day, but I had forgotten that it was a lawyer story, about a corporate tax expert who takes a legal aid case defending a group of aboriginals accused of murder. It’s a movie whose ending I have thought about surprisingly often over the years, but watching the rest of the story was more like first impression, and it’s a great use of a contemporary drama to deal with bigger issues rooted in deep time and our relationship with the planet. Its romanticization and appropriation of aboriginal culture is fair game for criticism, but gives the director license to let in just enough surreal wonder to let you find your own way into the real story, in a way that achieves genuine revelatory power.

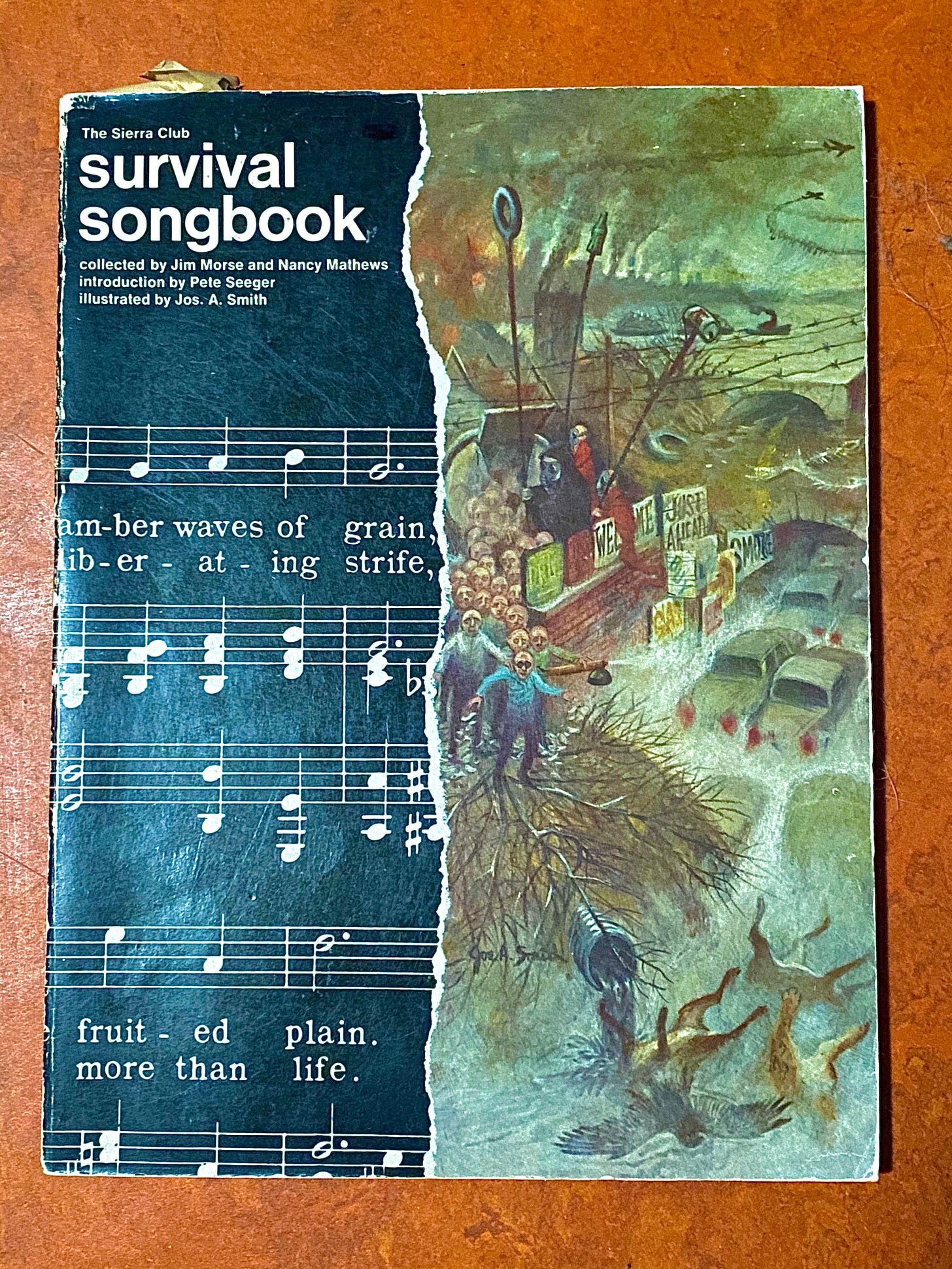

Those movies got me thinking about how much eco-drama there was in the 70s, from the PSAs I mentioned last week to the cheesy comics I used to read about the monsters created when you dump chemicals in the swamps and the 1971 songbook I recently acquired packed with 59 American ballads of ecological lament. The songbook has an introduction in verse by Pete Seeger, saying “songs won’t save our planet,” that that will only happen “when our heads are turned around.” The vintage of that message teaches you something different: that nature will save itself from us, at our expense.

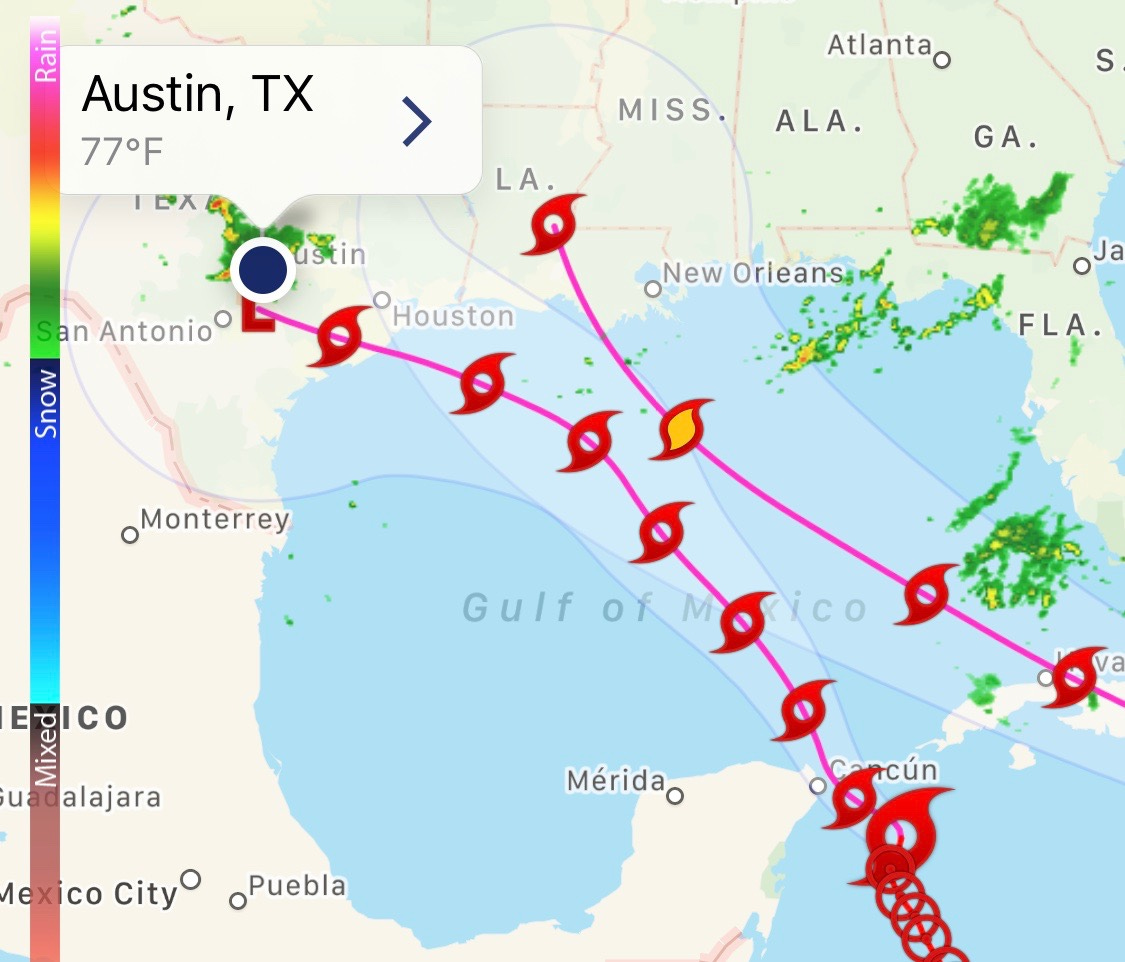

It was with all this on my mind that I read the news Wednesday that 750 million genetically-modified mosquitoes are to be released into the Florida Keys. A UK-based company called Oxitec has developed a patented strain of Aedes aegypti modified with a self-limiting gene that prevents the offspring from growing to adulthood. Males bearing the gene will be released into the population to interbreed with the locals, an idea that was approved Tuesday night by the Florida Keys Mosquito Control District Board of Commissioners. What could possibly go wrong?

The eco-disaster movie plot practically writes itself, even before you read that the company markets its Frankenstein bugs under the trademark “Friendly™ Technology.”

Sounds like a job for Man-Thing, the avenging spirit of the polluted Florida swamps.

Have a safe week.

Further reading and viewing

“Want a Vine That Will Climb? Try a Clematis”—lovely short article by Delmar Cain, at the Native Plant Society of Texas site.

The Last Wave, directed by Peter Weir (1977).

Long Weekend, directed by Chris Eggleston (1978).

Fever Dream, by Samanta Schweblin, published in Spanish as Distancia de rescate in 2014, and in English in 2017. Profile/review at The New Yorker.

Hurricane Season, by Fernanda Melchor, published in Spanish as Temporada des huracanas in 2016, and in English in 2020. NYT review here.

Indian Depredations in Texas, by John Wesley Wilbarger (1889), available in the public domain at various sites.

Circle Acres, a project of Ecology Action of Texas

“How the World’s Largest Garbage Dump Evolved Into a Green Oasis”—Pretty interesting NY Times article by Robert Sullivan from this week’s feed about the minimalist restoration of the Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island.

Oxitec corporate website, on the company’s Florida Keys project.