Mixtape concrète

No. 178

Last Sunday morning my daughter woke up wanting to get out on the water. It was an exceptionally beautiful day, the kind of sunny but cool spring weather we rarely get in Central Texas. I put the canoe, snacks and water on my back, she lugged the paddles and PFDs, and we put in right after breakfast, working our way upriver with frequent stops for swimming and investigating. At one point Octavia got the idea to sit half-submerged on the limestone bottom and meditate, as one might expect from a kid who attended a preschool where they gave out prizes for yoga.

Despite being a short distance from downtown, and in a densely urbanized area, the stretch of the Lower Colorado between Longhorn Dam in East Austin remains a remarkably wild and natural corridor, thanks largely to the foresight of locals who worked beginning in the 1980s to protect it for future generations. The plan was simple—push gravel dredging further east, implement setbacks and height and density limits to keep the built environment at a modest distance, and let the river rewild itself. It worked, as you can see in the above photo our friend Michelle took when we saw her and her family out for their morning walk along the high south bank.

The water is clear and clean, or at least the cleanest stretch of urban river in Texas. The bird life is abundant, especially in the tail end of migration season. We saw our first green heron of the season, admired the baby great blues in their nests behind the old warehouses, and nearly got crapped on by cormorants while doing so. In the past two weeks we’ve had close encounters with painted buntings, summer tanagers, redstarts, multiple species of flycatchers and warblers, and an indigo bunting. The waterfowl evidences a healthy fishery, and the canoe is a great way to see the swimmers up close, including Octavia’s first alligator gar. But the feeling that you better enjoy it while you can is hard to suppress. Especially when you also find yourself wondering, as you keep the bow in the channel, whether you may need to relocate your family to another country entirely to provide your kids their best shot at a healthy and happy future. Assuming you could even find a safe sanctuary from what’s coming.

The week that followed affirmed that anxiety, as Monday’s full Moon brought an abrupt and freakish August heat wave in the middle of May. It started with three days of triple-digit temps and smartphone heat advisories from the emergency management authorities, the first of which came on Tuesday, annotated by my wife:

Of course we all know what’s going on. And feel largely powerless to do anything about it, and increasingly resigned to the failure of our major institutions to change our course. We try to make sense of our rapidly morphing local and planetary realities with what information we can glean from a fragmented and untrustworthy media environment, stitching together a patchwork of algorithm-driven news clips, headlines from friends, bills in the mail, freakish changes in the weather, faces on the street. And the signs the natural world gives us, if we can manage to break the trance and give it a moment of our attention.

I’ve been settling into a new office in the guest house my wife designed and we built together over the last three years. Like our main residence, it’s a concrete bunker, but cozier and above ground, with an aesthetic deeply connected to the 70s, the kind of place that’s eager for a big terrarium and some hanging plants. Maybe that’s why, after I got my books onto the new library shelves and my stereo set up, I found myself digging into my archive of cassettes, which do a similar kind of splicing together. The way a mixtape made for me by my dead brother encodes otherwise unarticulated sentiments, or how sampling one’s own collection of purchased recordings accretes into some semi-coherent summation—a late capitalist ecology of memory.

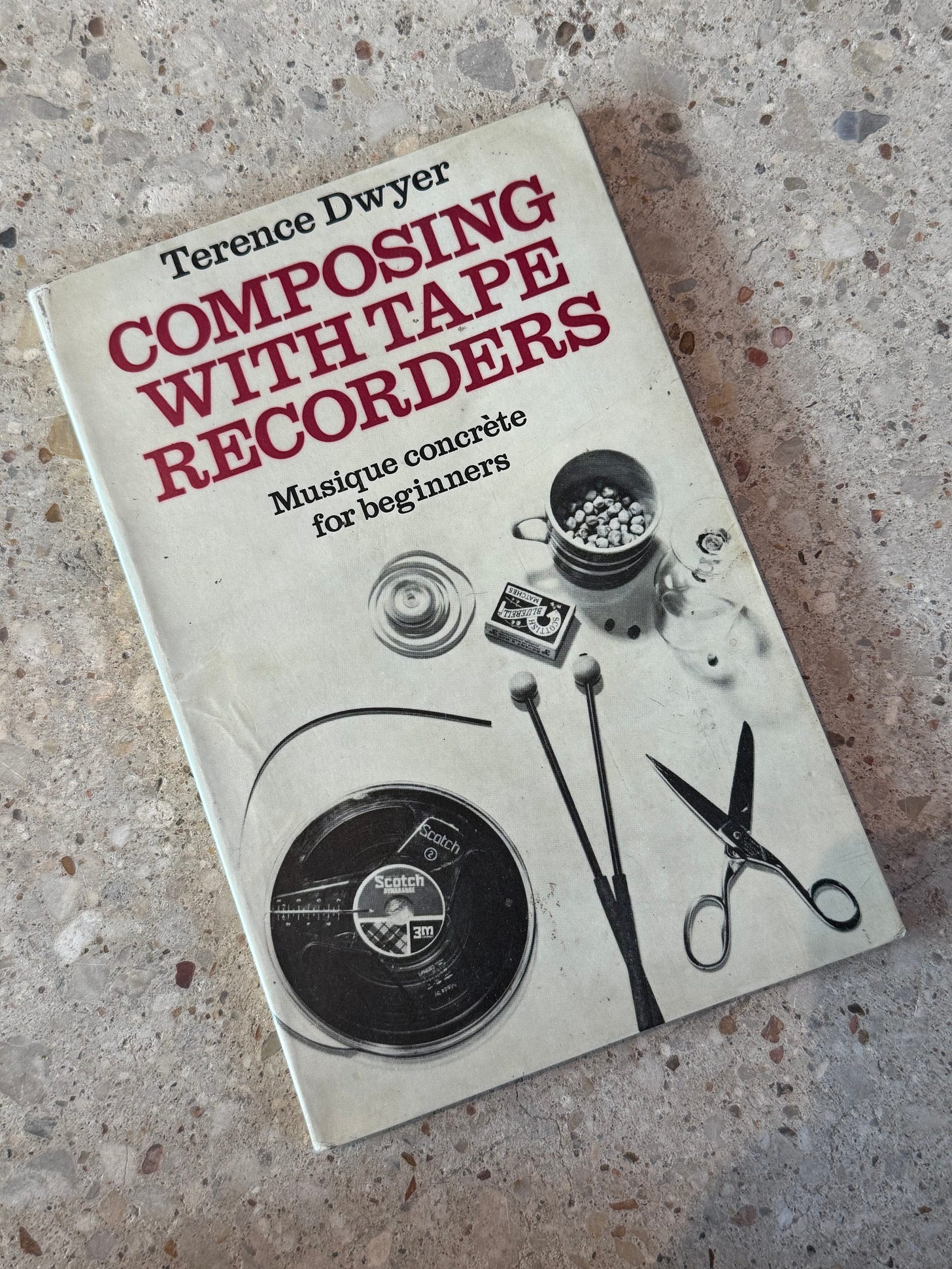

When I unpacked the above used bookstore find from a few years back, a very British 1970s DIY guide to “Musique concrète for beginners,” I got to wondering whether I might be able to conduct some similar experiments over the summer. Perhaps with field recordings from the simultaneously wild and brutal Anthropocene soundscape around our neighborhood. Idle dreaming, no doubt, as 2025’s doesn’t feel like the kind of summer likely to indulge time-consuming home hobby diversions.

After my event at First Light Books last Friday, I picked up the new issue of The Paris Review, curious to see what the cool kids are up to. When I cracked it open Saturday morning over coffee and read the first story, I was amazed to find myself suddenly dropping acid with Brett Kavanaugh and Clarence Thomas in the emergency bunker, while John Roberts weeps in the corner about the disaster that has occurred in the negative space of the story—“Crystal Palace” by Amie Barrodale. I was pleased to find such a potent Ballardian riff instead of the navel-gazing interiority I expected, and impressed by the characterizations, having worked around several actual members of the Supreme Court in my first law job as a Senate Judiciary Committee staffer. It was interesting to read such a clever narrative bend on the idea of states of emergency, as the real Supreme Court dithers over whether to call bullshit on the self-evidently specious ones currently being tested out.

The story got me thinking how we live in a moment of declared political emergencies that are nothing of the sort, while a very real planetary emergency unfolds in ways we all feel, but happens in such slow motion that it’s as if no one fully believes in it. We try to do our part, working to replenish biodiversity in our own home and garden, reduce our consumptive profile, and collaborate with our neighbors to cultivate and protect the health of our post-industrial corridor. But the political environment, with its angry silverback resurgence of insatiable extractive appetite powered by capital and paramilitary force, makes such efforts feel quixotic and quaint. As does the absence of a coherent alternative vision of how else we could live.

During the week I reread another book that I had unboxed over the weekend: a beat-up paperback of In Bluebeard’s Castle by George Steiner I bought after hearing him speak at Tulane in 1984. The lecture and the book both made a lasting impact on me with their erudite, allusive riffing on the big question that loomed over the second half of the twentieth century: how did the European cultures that achieved a hundred years of peace and prosperity between Waterloo and the assassination of the Archduke also produce the mechanized barbarity that killed 70 million people and culminated in the Holocaust? Steiner never really answers it, and some things in the text age badly, but it’s still a tremendous essay, with more touches on environmental issues than I remembered. It also ends with a remarkably prescient glimpse into the future from the vantage of 1971. A reminder that we can usually see what’s coming if we pay closer attention to the early indicators hiding around us in plain sight, even if we can’t change the weather our grandparents bequeathed us.

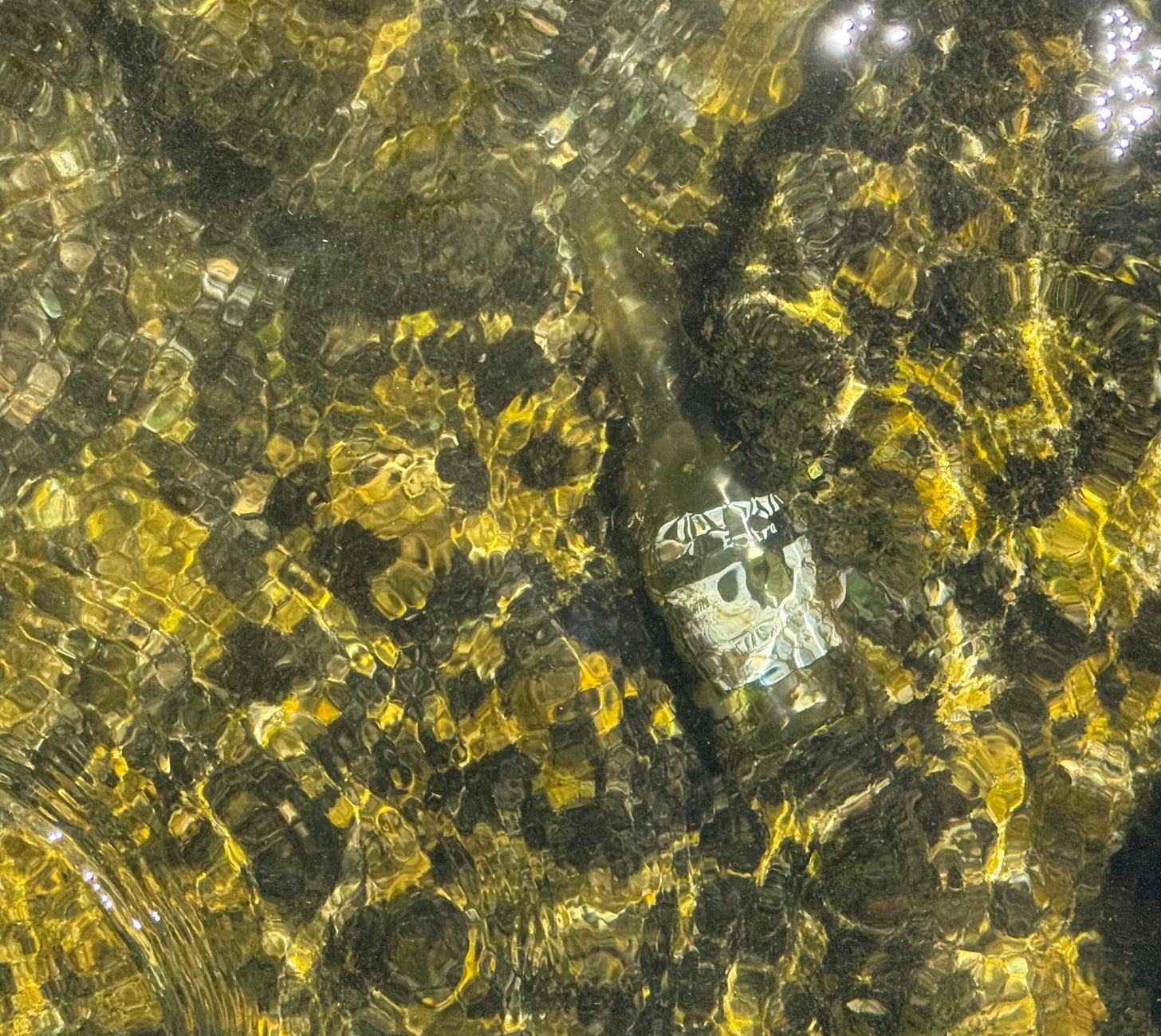

When Octavia and I got to the dam, we paddled over to visit some ducks loitering on a pile of rocks near the spillway, where the egrets and herons line up to catch the big fish that pour out from the floodgates. We stepped out of the boat to clamber around after the ducks finally flew off, and in the glistening water I noticed an old bottle of Corona, which triggered more 80s memories, including that awesome song of the same name by the Minutemen, which was not really about the beer. I could hear D. Boon’s plaintive opening line:

The people will survive

In their environment

The way he sings it, you can tell he believes it, but in the way of a conjurer trying to will a better future into being. I believe it, too, grounded in my witness of the resiliency of nature, of human beings, and diverse communities. The promise, and the problem, is that to get there we have to get through the summer that’s coming.

The Roundup

Thanks to the wonderful crowd who came out to First Light Books for my conversation with Abrianna Citta of Urban Austin Reads. That shop has quickly acquired an amazing energy as a vital community center, a kind of cultural oasis, and the way the design of the shop (by our friends at Thoughtbarn) can quickly morph from retail display to event spaces is remarkable. If you’re in Austin and haven’t checked it out yet, you should. And if you’re interested in getting a signed copy of A Natural History of Empty Lots, give them a call.

The other book I picked up there after my event was American Bulk by Emily Mester, a collection of essays about excess. I just started it, and the opening piece about the author’s Midwestern childhood going to Costco and the slowly revealed accumulative secrets of her sweet grandma from Iowa really grabbed me—a clever way to use memoir to more deeply interrogate our addiction to the accumulation of surplus.

The folks at Timber Press hooked me up with a copy of Wild NYC by Ryan Mandelbaum and Chelsea Beck, a wonderful guide to finding nature in the five boroughs. It’s really cool to experience the city through that prism, and the book does a great job of providing deep historical context for the rich field guide entries. I’m excited to get back and explore some of the places the authors describe.

If you’re looking for edgy futuristic fiction that’s not afraid to tell the truth, check out the new story collection Another World Isn’t Possible by Brendan Byrne, forthcoming later this month from Australia’s Wanton Sun.

Telling the truth about what’s going on right now in the real world, Michelle Nijhuis had a great op-ed in the NYT Friday about the battle lines developing around the idea of starting to sell off the U.S.’s public lands.

And over at 4Columns, a great review by Mark Dery of Robert Macfarlane’s new book on the idea of the rights of nature, Is a River Alive?

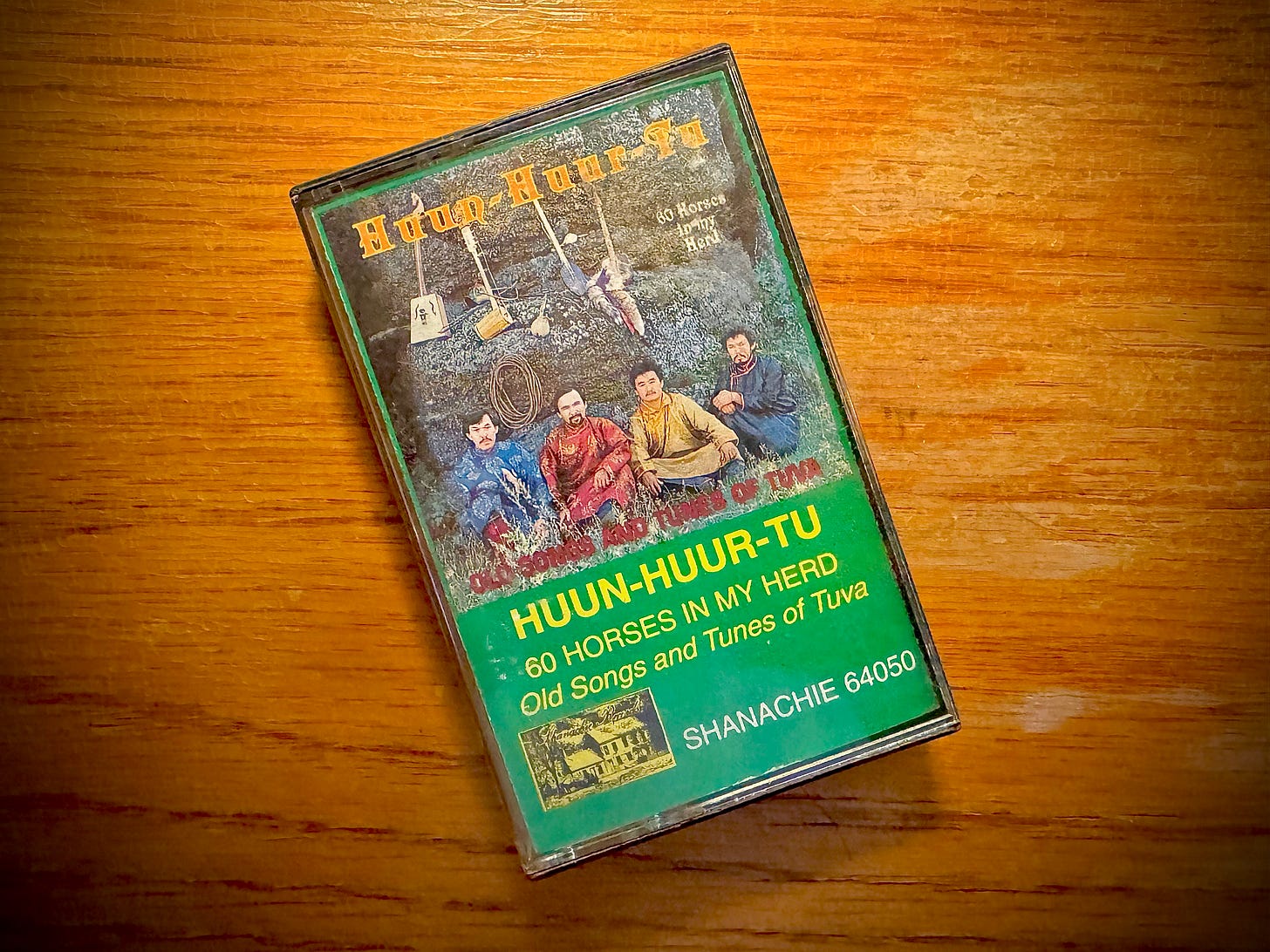

One of the old cassettes I listened to this week was 60 Horses in My Herd by the Tuvan band Huun-Huur-Tu. That got me thinking about Genghis Blues, an exceptional documentary I saw at a SXSW screening around its release in 1999. It tells the story of how blind bluesman Paul Pena, listening to Russian short wave radio in his apartment in 1980s San Francisco, taught himself the art of throat singing, and eventually managed to travel to Tuva and meet some of the voices he had heard over the airwaves.

I was delighted to read the news from across the Bay that Les Blank Films and the Arhoolie Foundation succeeded on acquiring their building, which also houses the amazing Down Home Records, on San Pablo Avenue in El Cerrito. I got to check out the building and the shop in February while visiting friends who live down the street, and look forward to going back and getting this T-shirt I left behind.

That also reminded me of a recent lunch conversation with a friend in which we found ourselves imagining the Werner Herzog adaptation of the Relación of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca. In the meantime, I’m going to check out Juan Diego’s 1990 Spanish-language version, which is now available free for streaming (with subtitles):

Sorry for the later than usual installment this week—some weekends it’s hard to carve out the time. Field Notes will be off the next two weeks, returning in June with a report from farther and greener fields.

Have a safe week.

If you ever want/need to move at one time I might have suggested up here, but instead of the stupid heat you're dealing with smoke from constant forest fires and more and more drought-like conditions every year.

It all reminds me of a t-shirt I saw the other day: Welcome to the coldest summer of the rest of your life.

late to read your latest, but oh! look at that clear river you paddle. too late for any of us to move, i've decided, even if we had the resources to do so. trying to be our best where we are closest to the land and to people.