Midwinter in the Tropic of Kansas

When we set out from Wichita the morning after Boxing Day, the sky was full of drones and geese.

Just one drone that we saw, a little one taking off from the Air Force base next to the Boeing plant by the Kansas Turnpike, but like geese, if you see one you can be sure there are others close by. My son and I once saw a next-gen stealth bomber landing there as we drove through in the early morning light, a flying wing like the ones they brought Opa here to build for them after the the war. Machines that mimic nature to keep it under our control.

The geese were everywhere, in their flocks of 12 or 20, flying south with a sense of urgency. Maybe they knew about the winter storm that was coming where we were headed. I saw them on the water there in the man-made lake at El Dorado, an awesome name for a town where they pump gas from underground and trap it to burn. Further north I saw a flock on a frozen farm pond, looking wonderfully dorky standing around jabbering on the ice with fat bodies on skinny legs. Their ubiquity made me wonder how many species that used to follow similar migratory paths are gone, and whether the geese will disappear too as the climate up north changes.

Every mile or so one of the farmers would have a Trump flag flying at the edge of the interstate, all of them already gone ragged in the Midwestern wind, one draped in threads across the barbed wire, a pioneer innovation that mimics the sharp-thorned branches of the bois d’arc tree.

We saw just one state trooper, in his Indian-fighting campaign hat, out of his patrol car and standing behind the concrete pillar of an overpass with radar gun in hand, ready to ambush southbound speeders. But the hawks are who really rule the interstates from northern Oklahoma into the Corn Belt. You see one every quarter-mile or so, on bare trees and billboards, most of them red tails with their snow-colored chests and wings the dark brown of winter wood, sometimes in mated pairs, lording over the denuded killing zone we created for other purposes. The vultures don’t seem to hang around for winter. Not where it snows.

Interstate highways seem an unlikely place to experience nature. They are routed for almost exclusively utilitarian purposes, with extra wide rights of way that keep the world at a layer of remove, and are primary attractors of the kinds of land uses that obliterate beauty—office parks, malls, industrial facilities and the kinds of small businesses that thrive on frontage roads. They are machines for the killing of wildlife. But the roots of their design are tied to Romanticism and its celebration of landscape as folk identity. So when we drove through Eisenhower’s home state on the Kansas Turnpike, I was reminded how the road was copied from the Autobahns Ike used to conquer the Reich that invented them. A military technology meant to be so pretty the citizens forget the real reason we built it.

The other thing about interstate highways is that they often follow the routes of much older roads, often roads built on the paths of pioneer trails that were once Indian trails and probably animal trails before that—transcontinental trackways made by buffaloes, and in some cases by the mastodons that didn’t long survive the arrival of the first humans who walked over from Asia.

We started our trip following the path of the Chisholm Trail, tracked sections of the Santa Fe Trail south and west of Kansas City, and ended our journey following the route of the old Jefferson Highway. All of these pathways follow deep vectors in the landscape, tying together far-flung parts of the continent we don’t often think of as connected. And while the interstates express our total domination of that landscape, the way raptors have adapted to them reminds us that our concrete highways are still part of nature, one that not just hawks take advantage of.

Between Fort Worth and the Red River, big patches of bushy bluestem, the Wilford Brimley moustache of native grasses, grew along the side of I-35W, in the rights of way and the unmowed acres of abandoned resorts and empty lots north of the new robot cargo airport. Probably my favorite of the Texas grasses, and the hardest one to encourage in our pocket prairie.

The ecologists will tell you that our freeways are major corridors for the dispersal of invasive plants, carrying seeds by wind and wheel to far-flung parts of the country. They are also zones where, in my lifetime, through a mix of progressive management and oblivious inattention, vestiges of the landscapes that were here before have started to reappear. People have started building wildlife bridges to mitigate the impacts our highways have on wildlife—they just completed one in San Antonio, and there’s a major one underway in Los Angeles to preserve the mountain lion population—restorationist innovations that optimistically embrace the idea that freeways can more intentionally harmonize with wild nature. It will be interesting to see what else they bring.

A wintry mix

Over the river and through the woods, to Grandma’s house we went, taking our toddler for the second time since her birth, and her first visit in winter. My folks live in southern Iowa on an oak savanna they have been restoring since the 80s, an acreage that was never really any good for farming. When they bought it, it was scrubby brushland, full of weedy ironwoods and cedars in the understory. They have burned it every year since, and the transformation has been dramatic.

It’s especially evident in summer, when the full biodiversity is evident to eye and ear. But I prefer the stillness of winter, especially because it comes with an absence of ticks. We got lucky, and it snowed. The first day, with good powder followed by freezing rain that coated it in an icy crust, and then a drier couple of inches that filled the forest with easy tracks. I found an old Flexible Flyer in the garage, and took baby for her first ride.

The tracks in the morning after a big snow reveal the the usual suspects on the move: rabbit, fox, coyote, turkey, and deer. So many deer and turkey that that other similar woodlands up there are being bought by wealthy hunters, most of them southerners, as personal game preserves. One wonders how the natives feel about that.

We did some tracking on our own, and baby learned to gobble.

My favorite spot up there is a patch of bottom land next to my folks’ place that has been turned back into the wetland it probably was before it became a cornfield. It’s a primitive but successful experiment in terraforming, with two bulldozed levees at right angles holding in the rainwater and runoff to provide a few acres of swamp for the birds, beavers and frogs. It’s the first place I ever had a close encounter with a coyote, on a winter day like the one I walked it last week, and the only place I’ve ever seen an entire family of beaver.

Down in the creek to the west, I saw a couple of the bald eagles that like to winter there, in a region where one used to only see crows, the bird whose call I associate with plowed fields and decimated ecosystems. Iowa used to be full of pheasants, but they have mostly run out of habitat.

It’s a heartening thing, seeing a swath of country beginning to go back to wild after a century and a half of agricultural subjugation. It’s a sobering thing, when you consider the extent to which those changes to more leisurely uses of the land reflect the slow-motion failure of the family farm-based economic system on which the country was founded. And the cultural consequences, as the townships into which the land was carved by the surveyors in the 1840s for settlement by pioneers and veterans become the playgrounds of wealthy people from elsewhere. Good for the land, bad for the people.

It’s harder to feel sorry for the heartland’s good old boys and gals when you travel back through Oklahoma, past the exits and water towers named after the vanquished peoples who once inhabited the rest of the country. The first one you pass after you enter from Kansas is the relocated home of the Tonkawa, the previous inhabitants of the area around Austin. The Salt Fork of the Arkansas River passes through there, just downriver from the Great Salt Plains, an American oasis where the migratory megafauna once came from far and wide.

Right before you cross the Red River into Texas, there’s an abandoned rest area off the southbound lanes, with steel pipe teepees lurking back there in the winter brush. North of Denton, I saw two dead coyotes by the side of the road, and one lone pedestrian walking south on the shoulder. One of those guys who would not call himself a pedestrian, was probably walking from Oklahoma City to Dallas, and who makes you wonder if someday that might be the main way the people that are left use those ancient trackways we see through the windshield.

While we were gone, the local coyotes who live behind the factories beneath the overpass were up to their winter friskiness, enjoying the stillness at the end of the year.

Children of the Corn

When we finally arrived home, exhausted from the trek, the mail pile included a large DHL package from Moscow. My author’s copies of the Russian translation of my 2017 novel Tropic of Kansas. The cover illustration features a mirror version of the landscape we had just spent the week traveling through, with abandoned grain silos, an old dead truck, and a lone figure walking the apocalyptic road who looks a lot like that guy I saw north of Denton, except he’s carrying a rifle.

There are a lot of guns in Tropic of Kansas. It’s the story of an insurrection in an alternate United States. When I wrote it in 2013-14, that idea of an American version of the Arab spring, an #Occupy with AK-47s that rises up against a media personality turned authoritarian president, seemed almost too implausible, and by the time I sold the book this time in 2016 something very similar was already starting to happen in real life.

The book’s penultimate scene features a mob ransacking The White House after the rebels retake Washington. The mob is trying to overthrow a dictator rather than keep one in power, and the intent of the book is to repurpose our revolutionary creation myths—the third rail of our political culture—toward more emancipatory ends. But I couldn’t help be sickened by the parallels as I watched the events unfold Wednesday in the building where I worked for five years before and after law school. Especially as I wondered whether any of those wannabe real-world insurrectionists might have been influenced by the book, which was read pretty widely, or by any other of the similarly-themed books that appeared that year and after—fantastic fictions of a Second American Civil War.

It may be a stretch to try to tie this week’s horror show to the usual themes of this newsletter, but I think the connection is there. I saw it in the way so many of the Capitol rioters were dressed like actual Vandals, like the guy in the horned helm and fur cape going all Conan the Barbarian at the President of the Senate’s dais, and in all the flags they were carrying that I had seen on the Texas beach last summer, and on Midwestern flagpoles last week, with Trump’s face pasted onto the body of Rambo. Those rednecks gone wild were channeling deep memes born in our conquest of the American wilderness.

Rambo is what you get when you send the archetypal backwoodsman of American folklore to Vietnam or Afghanistan—a weaponized version of the farmers and trappers our forebears used to scout new territory, put the prairies under the plow, turn Indian trails into highways. Figures who express the wild in order to raze it, and embody the barbarity we used to conquer the frontier. And when you drive cross country and see how economically and ecologically exhausted most of the agricultural heartland now is, it’s not that surprising to see post-apocalyptic Visigoths on the Capitol steps. You know many of them come from places like that. They’re as all-American as the marauding white scalpers of Blood Meridian, mutated through the insane mirrors of our postmodern media culture.

You can see the resilience of wild nature wherever you go in this young country, especially in the parts where the original business model has failed so badly that dystopian novelists driving through see the material for their next book. You can also see the Malthusian inflection point looming on the horizon, as people become the main migratory species on a planet growing ever more crowded, and the enforcement of territorial boundaries become the animating force of politics. No wonder all those rich guys are buying up remote estates, building bunkers, and trading in their Range Rovers for Cybertrucks. Imagine if they invested their money in helping to really fix those broken ecologies that are the real root of our problems.

That project is up to the rest of us, and spring is coming.

Further reading

For more on outdoor class conflict and the gentrification of the wilderness, check out this Ian Frazier piece at The New York Review of Books, “The Plushbottoms of Teton County,” reviewing Justin Farrell’s Billionaire Wilderness: The Ultra-Wealthy and the Remaking of the American West, a study of how the area around Jackson, Wyoming has become the most economically divided part of the USA.

For more on humans as migrants, check out this piece by Anna Badkhen, also at NYRB—“‘Bright Unbearable Reality’: Migration As Seen from Above.”

For more on the deep natural history of American highways, check out this piece on how US Route 12 between Detroit and Chicago follows a path first blazed by mastodons.

For more on the folkloric archetype of the American backwoodsman, as well as figures like the Yankee peddler who walks into town with a cart full of shiny things, sells the yokels things they already own, and then gets run out of town too late to remedy the damage he’s caused, check out Constance Rourke’s American Humor.

For more on how the contemporary white power movement traces back to the post-Vietnam grievance culture of the 1970s, check out Kathleen Belew’s excellent 2018 book Bring the War Home.

For a cultural history of postwar stories of American insurrection, check out Brendan Byrne’s 2017 piece for The Intercept, “The Speculative Civil War Novel Comes Home.”

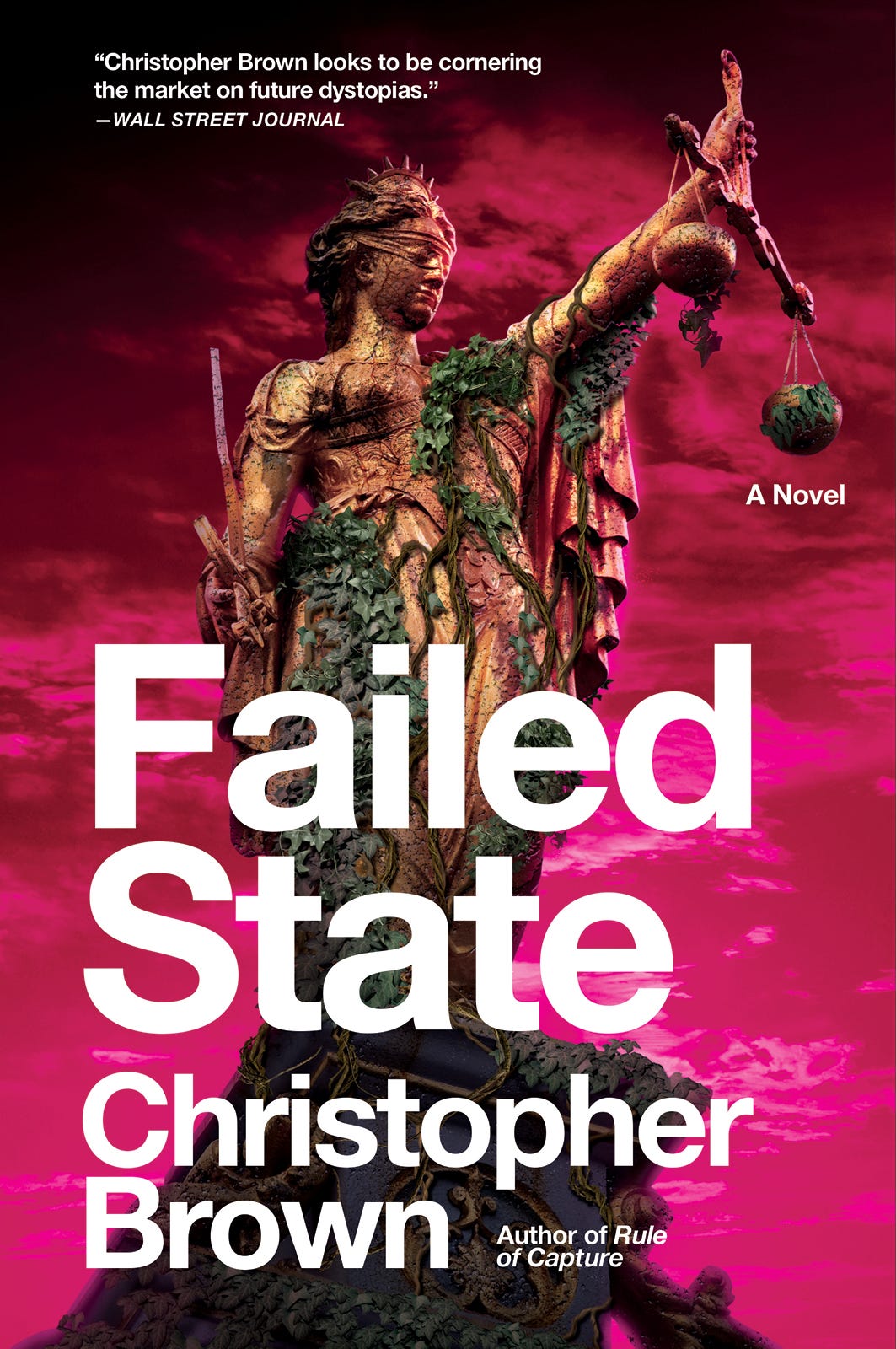

And if you’re interested in a more utopian story of people trying to build a better, greener future in the aftermath of ecological crisis and a second civil war, the ebook of my latest novel Failed State is currently available for a promotional price lower than a cup of good coffee.

Bonus Mothman footage

For those who made it to the end, here’s a remarkable trailcam shot taken while we were away—what must be a barred owl, fleeing the scene after a strike, too fast to be properly captured by even the one-second delay, but even then presenting an awesome monster. Imagine how the mouse feels when this thing appears in its peripheral vision, right before the end.

Have a safe week, hopefully free of any more violent coup attempts.

I love seeing all these things through your eyes--the things we've done, the people we've been and who we are now.

A book that I’d recommend is The Big Roads: The Untold Story of the Engineers, a visionaries, and Trailblazers Who Created the American Superhighways by Earl Swift, which is an interesting look at the history of how those highways came to be. I hadn’t heard that they’re highways for invasive plants, though.

My wife and I love spotting the hawks as we drive between here and PA to visit her family. They perch at a fixed distance between one another, which we’ve always found interesting.