Megaphasma and the Geoengineers of the Stratosphere

No. 158

On the last Sunday of July, we headed out a little before 1 p.m. for our daughter’s friend’s 5th birthday party. As we loaded up, I noticed a beautiful spider: a Texas orb weaver that had spun its trademark zig-zag web in the weedy brush that grows there in the right of way outside our gate, anchored by the firmer structure of our beat-up old mailbox. A common bug, but still remarkable, especially to a child who has never seen one. When I showed it to her she was wary at first, but accepted my explanation that it would not harm her, and then was taken by the marvel of its size—as big as a tarantula, but with the shape and coloration of a little eight-legged banana. Especially once I blew on the strands of the web, and the orb weaver danced off to the opposite end.

The Godzilla-themed party was epic, with giant lizard gods everywhere you turned, and an old school slip-and-slide that eventually got extra drenched by a big summer thunderstorm. My kid took a momentary break to hand me a half-eaten chocolate cupcake, from which dangled a little paper topper featuring the war-faced torsos of Gojira and Kong. And when we got home, we found the aftermath of a fight between two tinier behemoths. At the bottom of the orb weaver’s web was a specimen of the biggest bug I have ever seen outside of a museum: a giant walkingstick.

The first time I encountered one of those was on our front door, trying to get into the house. So I guided it onto my hand, and was amazed at how much, with that massive yellow-orange-green exoskeleton stretching out the length of my forearm, it felt like a giant mechanical bot. It even had a Kaiju-worthy name: Megaphasma. But the one we encountered when we returned from the party had no more walk in it. We quickly realized it was dead, hanging on a damaged section of the web, its rigid body bent like the steel of a car after a wreck. And so, further inspection revealed, was the spider, the big egg of its white tiger-striped abdomen pierced and drained. I imagined the cinematic battle that must have occurred, the Marlin Perkins-grade narration writing itself in my head about the struggle that killed both predator and prey.

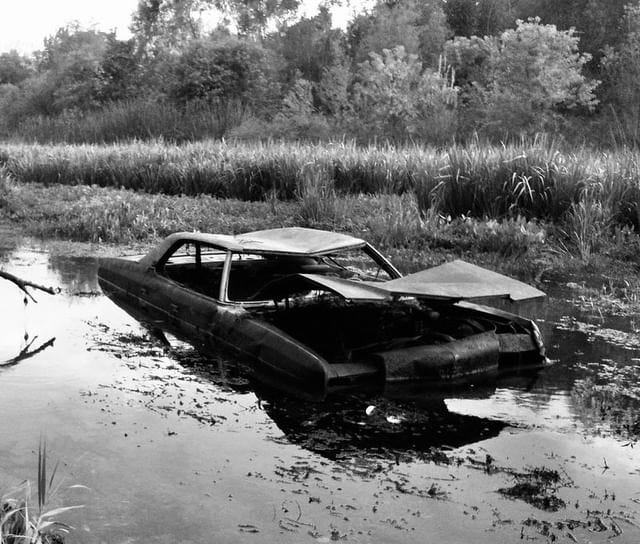

It was reassuring to see the aftermath of that battle of Lilliputian behemoths in such a seemingly blighted spot: a little corner of a mostly industrial neighborhood, where the summer vegetation hides a recently dumped tire, empty beer cans, and the marker of a buried petroleum pipeline. But that sliver of right of way is allowed to grow wild, as is our yard on the other side of the gate, and regularly demonstrates the habitat that a little bit of interstitial wild space can provide. Evidence that was affirmed by the even bigger exemplar of Megaphasma I found on our bedroom window Friday evening, one who looked to have survived her battles to a gargantuan green maturity.

I had been reading this week how July 22 was the hottest day on the planetary meteorological record, and it felt that way in Austin after Sunday’s storm cleared out and Texas summer returned with full August force. The town is half deserted, those who can having fled for the mountains and those who can’t mostly staying inside. When I turned off the air-conditioning in my trailer office for a few minutes Thursday afternoon to eliminate the background noise while I recorded a little book-related video, I started cooking within five minutes and realized I would have to defer the undertaking until morning.

But when I stepped outside, I was quickly reminded of how even our most brutal season can be lush with signs of life abounding, especially with a little bit of a rain to juice the plants and streams. The tangerine-colored Gulf fritillaries who flutter around the passion vine that crawls up the chain link, the goldfinches that eat the sunflower seeds straight from the flowers, and the exotic parakeets who come around to pig out on the fresh pods of the honey mesquites.

In the desert of summer, you get less picky about which of the species bringing diverse life energy to your immediate environment are native, and which could be called invasive. The monk parakeets have only ranged freely in this country since the late 1960s, but seem to have fully naturalized to our Anthropocene domain, finding our metal infrastructure towers excellent substitutes for the tall jungle trees they nest in back home in South America. We have native sunflowers, but most of the ones growing in the yard are also naturalized exotics. And one wonders whether even the mesquites, a Texas tree with a Nahuatl name, were as common in this particular zone before we brought the Blackland prairie under the plow.

Tuesday morning on my run I spotted three black vultures perched on a lamppost above the tollway bridge, waiting for the next bit of roadkill to become available, or perhaps chilling after picking one clean. That’s a good spot because they also get the things the river leaves behind after the overnight dam releases, including the occasional big fat carp that gets beached. At lunch later that day I would read about how the demise of vultures in India due to a drug for cattle resulted in half a million human deaths that would have been prevented by the scavenging of cow carcasses and the diseases they otherwise spread. “Ecosystem services” is the bland term the economists and ecologists use to describe the economic benefits wild nature provides the human machine, as if the only path to a greener future is the one that travels through the blackboard dream of Pareto optimality.

The next day’s paper brought a different report about the economics of slow-motion environmental catastrophe, with a long feature (also on the front page of today’s Sunday Times) about the serious consideration being given to one scientist-turned-entrepreneur’s proposal for “stratospheric solar geoengineering”—pumping millions of tons of sulfur dioxide into the upper atmosphere to cool it by blocking the sun, on the theory that humans cannot realistically reduce our emissions soon enough to otherwise avoid catastrophic warming and we have nothing to lose mimicking the aerial cover that follows a massive volcanic eruption. Scary stuff to ponder in either scenario.

My other lunchtime eco-reading this week was via Bruce Sterling, who shared this remarkable Ars Technica piece about “hybrid swarms”—the circumstances in which the 25% of plants and 10% of animals capable of interbreeding do so, including as the result of human interventions in the environment. It’s especially common among plants and marine animals that don’t rely on one-on-one sexual coupling to reproduce, and examples abound of hybrid fish resulting from two species being trapped in a small area for an extended period of time, such as when a dam is erected. Africanized “killer” bees are a well-known hybrid created through human intention. It turns out most species of what we consider wild rice show genetic heritage from domesticated rice, carried across the planet by migrating members of Homo sapiens who hybridized with the Neanderthals and Denisovans they encountered when they walked out of Africa fifty or sixty millennia ago. Humans as Promethean coywolves, creating the conditions for other hybrids to flourish.

We live near the last of the series of dams that control the wild waters of the Lower Colorado River. It’s a profound ecological dividing line—when my son was in fifth grade I helped him do a science report comparing the diversity of birds observed above and below the dam, and the contrast was astonishing. The herons and egrets prefer the shallows of the natural channel below the dam. But they especially love the weird opportunity created by the spillway, lining up all year round on its concrete ledge to catch the big fish spilling out through the gates from the bottom of the lake. Human fisherman like it there too, and in high summer you might catch some of the young guys who cast nets to see what’s trapped in the pool.

It was only a couple of years ago that I learned eels also shelter near that spillway. In their case, they do so because they are blocked. They swim all the way here from the Sargasso Sea, amazingly, up the mouth of the river at Matagorda, during the juvenile phase of their lives, and hang out here through their hermaphroditic adolescence, until they differentiate and then swim back to their saline home waters north of the Bermuda Triangle. I’ve talked with some of the folks that study them, and scientists only seem to know a little about the lives of these creatures, who are especially elusive in the period when they are stuck in East Austin. I wonder what strange evolutionary adaptations they may develop, as they loiter in the recesses of the dam’s limestone shelf.

Living in a zone like this urban edgeland where we made our home, you start to see for yourself little everyday examples of how resiliently nature adapts to the challenges and opportunities we create, and of how permeable the boundaries between species can be—sometimes as illusory as the boundary between human space and wild. Or between native and invasive. You also realize how irreparable the change we have caused is, even when you personally witness the wonders of a native plant-based restoration, as we have on our blighted urban acre. The natural history of the future seems likely to be weirder than we can imagine, full of Anthropocene chimeras occupying rapidly changing zones of dynamic transecology.

I suppose that means we will evolve along with the world we have overheated, and I hope we can better learn how to let nature’s “ecosystem services” do the engineering for us.

Extra credit

On the subject of hybrids, the new issue of Texas Monthly has a great piece by Forrest Wilder on the ghost wolves of Galveston Island—coyotes that evidence interbreeding with the otherwise extinct (in this state) red wolf—and how their habitat is threatened by the new “Margaritaville” development about to break ground.

The early morning sky has provided a nice counterpoint to the heat of the day this week, with Jupiter and Mars sharply visible in the east around today’s new moon. By the end of the month, the astronomers advise, six of the planets of our solar system will be visible in the early morning across the arc of the sky. Keep your binoculars handy, and get up early enough to check it out. Day-by-day details here.

Over at Instagram, the folks at Timber Press have begun harvesting some of my black-and-white photos that didn’t make the final cut of those that accompany the text of A Natural History of Empty Lots, and I’m excited to see what they pick as they ramp up the campaign leading to the book’s September 17 launch date. Click through the embedded post below for more:

On the Timber Press website, they have made available a preview, in the form of a “missing introduction” to a book that does not have one.

And for those of you who have already preordered the book and asked to get in on the print version of the newsletter I’m starting, I’m hoping to get the first installment to the printer this week and out to you in the mail by mid-month. (Email me at chris@christopherbrown.com if you’d like to get in on that.)

Stay cool and have a safe week. Field Notes will like be off next weekend, as we plan to be in the field—looking for hybrids.

Two recs for you (both of which you may already be familiar with, however...): for the Indian vultures, episode 579 of the podcast 99 Percent Invisible is called "Towers of Silence" and is well worth listening to, and the book Eels by James Prosek is excellent, although recently overshadowed by another book on eels I have yet to read, by Patrik Svensson.

Your latest post inspires me to finally procure some mesquite bean flour and start working on some recipes, Christopher ✨