Mastodon Chiclets and heavy metal bumblebees

We’ve stayed close to home this week, digging our way out of the work that piled up after nine days at the beach, and avoiding unnecessary excursions out into the coronavirus hot spot urban Austin has become. But there’s plenty of wildlife to take notice of, even in the 200 feet I walk from our house to the old Airstream trailer I use as my office. Lately I’ve started to pay more attention to the Halloween pennants that seem to be everywhere this summer, especially in our wild yard. We see a tremendous diversity of dragonflies and mayflies here above the urban river, but these are the ones we see most often in the pocket prairie we have growing around our house and on our roof. The Halloween pennants in our yard are not as orange as the name suggests, or as the photos in the guidebooks evidence, but they seem bigger (maybe it’s a Texas thing), and their tiger-striped wings make them easy to spot, even in motion.

I love when you can get close enough to make out the evidence of life lived on the body of an insect, like the chips in the wings on the one pictured above that I found alighted on a plant by our front steps. A week at the beach watching shorebirds cruise the currents makes you pay more attention to the way creatures fly, and the Halloween pennants are pretty cool—one of those insects that moves with a heavy metal lumber that seems to defy the laws of physics, like some dream machine off an old Roger Dean album cover. There are a lot of bugs in the air like that here in the peak of midsummer, when the cool-colored wildflowers of spring are gone and the hardier yellow flowers open to soak in the hot sun.

We have a patch of yard along the west side of our house that was overgrown with brome grass this spring, an insanely opportunistic winter invasive they say was introduced as a remedy for the Dust Bowl. The only good thing about brome grass here is that it is easy to pull from spring soil, but when I was done weeding it in March all that was left was dirt. So I reseeded that patch with Blackland Prairie Mix from our friends at Native American Seed, and thanks to good rains the first season recovery is surprisingly lush, thick with partridge pea, prairie tea, and some of the tallest Maximilian sunflower I’ve seen—lean green stems that grow up above the grass spreading milkweed-like leaves until they are ready to pop with multiple heads of bright yellow flowers. A native plant that’s adapted to regularly shoot ten feet into the sky before blooming gives you an idea of how thick the grassy carpet of the Texas prairies must have been.

The color-coordinated partridge pea stays closer to the ground, but is a good thing to find growing in soil that used to house a petroleum pipeline. The ecologists say it is one of the most phytoremediative plants of the prairie, with roots that host nitrogen-producing microorganisms that bring vitality back to the soil. It was one of the first flowering plants we saw the season we began our restoration eight years ago, slowly diminishing as some of the harder-to-grow native grasses began to take and mature. The partridge pea flower seems especially adapted to the big bumblebees that show up this time of summer, and the carpenter bees I have been seeing this week—maybe the most heavy metal of all the flying creatures we see in our yard, a muscle car-black hairless bee the size of your thumb that moves through the air in a way that reminds you of the military helicopters we often see flying over us toward the nearby airport.

This is also the season when the bois d’arc trees start to drop their brain-like green fruit onto the path. We have two of those trees growing just to the east of our front steps, planted by our botanist neighbor from whom we bought this lot. The bois d’arc trees were probably not as historically common this far south, but they are a cool plant and provide nice shade for our entry, even if their thorny branches are the bane of the pruner, more likely than mesquite or huisache to draw blood from gloved human hands.

Though the Texans call it “bodark,” with a long drawl on the “o,” the bois d’arc tree was so named by the French explorers who observed that it was the wood the Indians preferred to make their bows, an experiment I hope to someday try with our daughter and her archery-loving older brother. The bow-wood grows fast, and the early settlers of eastern parts of the Midwest like Illinois used it as naturally occurring barbed wire before the metal suppliers caught up with them, planting trees in rows and tying the branches to grow together. But it’s the fruit that first really gets your attention, green gnarly globes the size of softballs that weigh down the branches and then drop to clutter the path, heavy enough to stub a sandaled toe. The only critters in our yard that seem to eat these “Osage oranges” are the squirrels, who nibble off chunks, but the other popular name “horse apple” gives you an idea of the cowboy experience of the plant.

When you learn that the fruit is likely co-evolved to be eaten and spread by the mastodons, wooly mammoths, and giant sloths who once roamed the plains, you gain a fresh appreciation of the deep natural history it encodes, and a healthy sense of the fleeting impermanence of your own simian existence, pandemic or not. When you remember that all of those species of megafauna disappeared after the first wave of human settlers made their way to this continent, you get a healthy reminder of why big wild animals are now rare across the entire planet, and how ancient the Anthropocene really is.

Summer in the secret woods

Saturday morning baby and I went for a long walk at sunup. I take it as further evidence of the intrinsic pleasure children take in nature that one of her first words is “backpack,” for the awesome Deuter child carrier that lets her ride above my shoulders on crazy excursions into the urban wilderness. We went down to the river, and admired the thick foliage growing on the rocky bank that not too long ago was a place where they dredged gravel, but there was a lot of the dog-killing algae there in spots. so we decided to see what was going on in the riverine woods of the floodplain.

It’s hard to really convey in words or photographs the quantity of human trash that the river leaves behind after a flood. It’s been five years now since our last really big one, and enough dirt is there to support foliage growing up over even the pockets of floodplain that looked like involuntary landfill not too long ago. But you can feel it underfoot, especially when bushwhacking with a baby on your back and two amped-up hounds on long leads. And yet, as long as the people stay away, the woods are full of life. Like this coyote loping through our backyard last Friday before dawn, coming from the fenced-off empty lots behind the nearby factories.

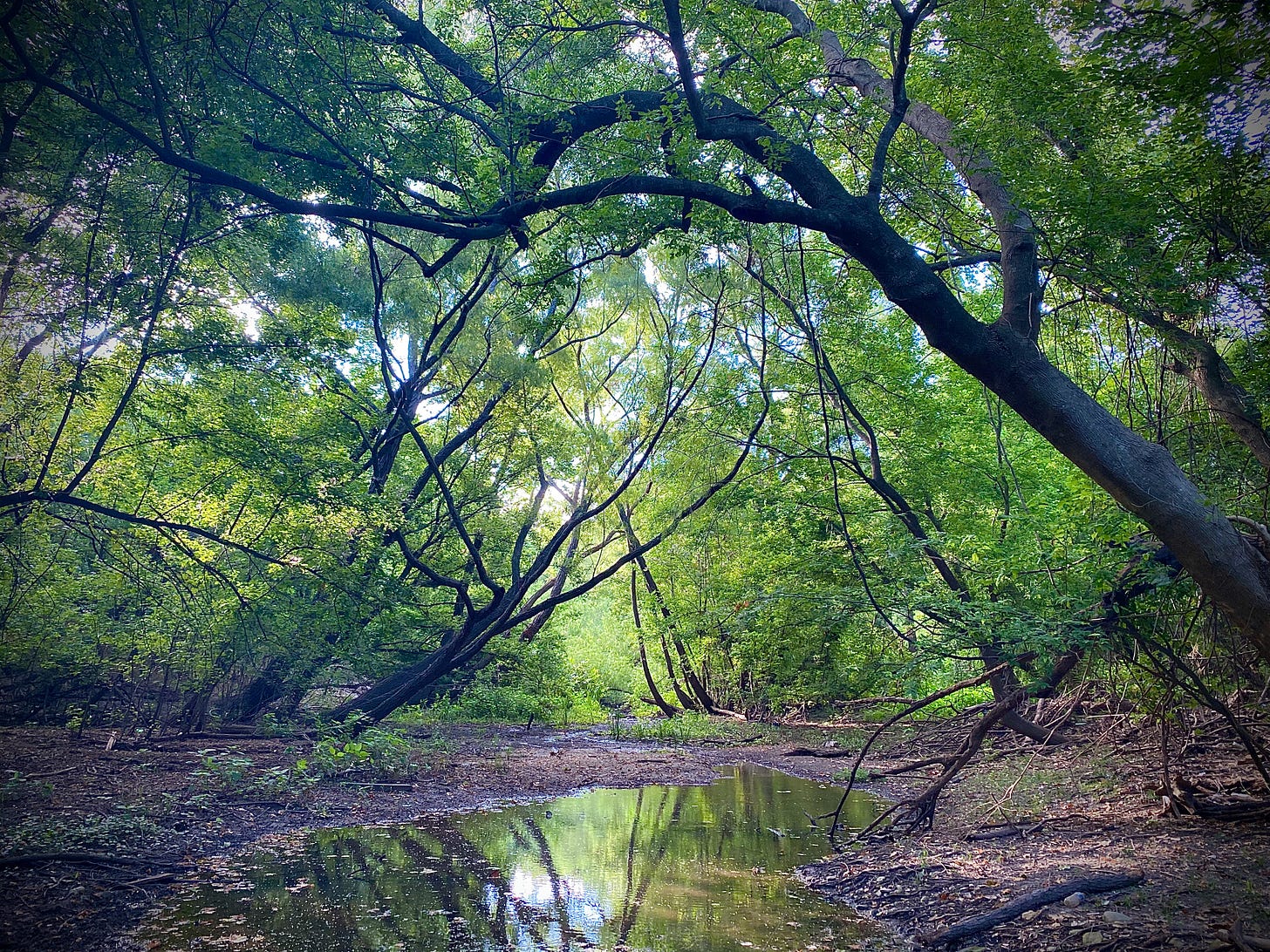

The coyote may have been headed to the spot where baby and I finished our walk—one of the first spots in the woods that our entomologist neighbor (married to the aforementioned botanist—the story is they met because the bugs he was studying were eating the plants she studied) showed me when he could tell he was in the company of a fellow weirdo of the urban woods. It’s a kind of grove, a spot down in the floodplain where the engineered municipal drainage ditches deliver storm water from the roads, roofs and parking lots of the industrial properties above the bluff. The water collects in a kind of stagnant lagoon before turning into a small creek, and over the water grows an archway of tall skinny cottonwoods and other fast-growing trees. It’s a spot with a vibrant stillness, a place where what’s left of the wild does its sun salutations when no human is looking.

In the winter when the warm morning dials up down there after a cold night, thick mist comes up off the water, and if it weren’t for all the trash and the sounds of guys cutting steel at the top of the hill you might forget where you really are. The first time I found my own way to that spot, there was a big barred owl sitting there watching me in one of those branches, and when you lock gazes with those enigmatic eyes you gain an immediate appreciation of the folkloric power of those birds. The first time I took baby out into these woods last fall, we heard one, and then saw it. It stayed there in its perch on the branch of a hackberry for what seemed like a long time, long enough for an infant to take notice of it.

Pictured above is another barred owl I saw back in March, in the early days of the quarantine. I came upon this one while trail running, and took this picture with my phone. With animals like owls, you feel lucky to have them watch you back long enough to capture the moment, and if they let you a pull out a shiny object and aim it at them with your opposable thumbs you feel like you have earned a wary tolerance (if not welcome) that comes from them watching you a lot more than you know.

Harriet Tubman, Master Naturalist

Speaking of barred owls, this week I read a fascinating story in Audubon about Harriet Tubman and how she used the bird’s short-short-long nighttime call as a signal when guiding people on the Underground Railroad. The whole profile is pretty revelatory, of how Tubman’s childhood experience as a slave gave her the knowledge of the woods she needed to help others escape to freedom across a dark and dangerous landscape:

Harriet Tubman spent much of her young life in close contact with the natural world. Likely born in 1822, she grew up in an area full of wetlands, swamps, and upland forests, giving her the skills she used expertly in her own quest for freedom in 1849. Her parents were enslaved, and Tubman’s owners rented her out to neighbors as a domestic servant as early as age five. At seven, she was hired out again, and her duties included walking into wet marshes to check muskrat traps. Tubman also worked as a field hand, in timber fields with her father and brothers on the north side of the Blackwater River, and at wharves in the area. All of this helped when, later, Tubman made 13 trips back to Maryland between 1850 and 1860 to guide people to freedom.

Audubon: Harriet Tubman, an Unsung Naturalist, Used Owl Calls as a Signal on the Underground Railroad

Life outside in the interstitial city

This week the bots inside my phone served up this picture I took five years ago, crossing an old bridge here in our neighborhood. A vignette from before public camping was decriminalized last year, and the safe places for homeless people in Austin were maybe not so safe. I volunteered for our local homeless count last year, trying to put my knowledge of these pockets of urban green to a more humanist use, and even as you see how many people are living out there under bridges and in unofficial parks, you can’t help but conclude that particular census misses a lot of people who are better at hiding than you are at finding.

Have a safe week. In the meantime, here’s one more trailcam coyote—likely the same one as showed up on the other video three days later.

And for those of you among the torrent of new subscribers this week, after my June post about the Flight of the fire ants made the front page of Hacker News (thanks for the tip, Andrew!), stick around until winter and you’ll find a lot more coyotes in these pages. In the meantime, you can check out this post from February: The coyotes of Soylent Green.