Mammoth resurrections and river restorations

The nights are dark here at the edge of the woods at the edge of town, especially in summer on days when the moon sets early. The glare of the central city still dulls the sky, but you can see the near planets and the brighter stars, and when I walk from my trailer to the house I look out into the inky black of the empty lot to the east and wonder what’s making that noise. That darkness is as much a part of the urban wildlife habitat as the trees, and even more threatened.

On the hot nights of August as I sat in the living room reading, I would often hear a dog barking in the near distance, a bark that sounded just like our dog Katsu when he would monitor those night woods from his high perch, before he died in June. The barking sounded so much like him that I wondered if it was his cantankerous ghost. I heard it again Tuesday evening, but when I stepped outside to hear it better, there was nothing. Just the croak of a nearby toad, and the soft cacophony of the bugs.

The days have been bright and sunny since Labor Day, with refreshingly cool mornings and tolerably hot afternoons. Sunday afternoon as I ran over the dam, I spotted a dude walking across the river with a bassinet in one arm and a baby in the other, there in the spot where the big cattle drives used to cross on their long journey from South Texas to the railheads in Kansas. You can see the ruts in the limestone there. Along the edge of the spillway, adolescent eels have settled in after their long journey here from the Sargasso Sea, hiding in holes all day and coming out at night to feed. In time, they will develop differentiated genders and the urge to breed, and head back out to the salt water. For now they enjoy the life of androgynous, limbless teens, hiding in plain sight in their unlikely urban habitat in the aquatic aorta of the fastest growing city in America.

Sixty years ago that green river hidden behind the factories of East Austin was one of the most toxic sites in America. Rachel Carson wrote a whole chapter about it in Silent Spring. Five blocks from the dam, in metal sheds you can still find there along the train tracks, just up the street from the nonprofit hipster coffee roaster and the new private club for silicon millionaires, they used to manufacture and distribute a cocktail of DDT for the cotton growers that once were common around here. Powdered chlordane, toxaphene and lindane washed into the storm sewer and flowed straight into the river, and killed the fish for a hundred miles downriver.

Six decades isn’t long in ecological time, but it was enough for this corridor to recover to the point where the Lower Colorado from Longhorn Dam to Walnut Creek is the only urban river in Texas to qualify as a “pristine waterway” over a decade of testing. Not some anachronistic remnant of what once was, as I thought when I first found it, but an exemplar of nature’s capacity to clean itself if allowed a little time and space to do its thing. It has been preserved through a mix of intention and inattention, but mostly the latter, as a riparian edgeland inadvertently protected through the industrial zoning of the streets above it, and through the prohibition of the gravel mining that used to be allowed. As the old Quonset huts turn into beer halls and the Range Rovers prowl the backstreets looking for deals, you can’t help but wonder how soon it will be trampled by all the humans who just want to have fun.

For now, the neighborhood above the river maintains a curious balance between industry and entropy. Tuesday morning I came upon a huge flock of sparrows hanging out on the sectional sofas someone recently dumped by the loading dock of the abandoned lighting factory. They were dining on a huge bag of restaurant flour that somehow found its way there to that asphalt by the bus stop. The bag had burst open and spilled some of its contents onto the pavement, and the white powder was decorated with the tripod tracks of tiny dinosaurs.

Across the street from that spot stands an older industrial building from before World War Two, with busted glass bricks in the facade of its decorative flourishes and a palimpsest of peeling paint over the generations of graffiti its elegant walls attract. Inside they operate some kind of salvage business involving used medical equipment, and the proprietors seem pretty tolerant of the kids who use the building as a backdrop for their digital performances. Sometimes they like the street art enough to leave it up.

At the west end there’s a little alcove that was especially popular with the Instagrammers until this old-looking dude, who is probably not really that old, settled in there not long before Covid hit. He accumulated furniture and clothes and trash, and was almost always there, sleeping or shuffling around the intersection, a quiet sentinel with ethereal eyes. In the winter I tried to check in with, and gave him a good sleeping bag and some cash. When the storm was coming we gave him a heads up and he found shelter, then returned. The business didn’t seem to mind him, even as the quantity of trash became epic, until Thursday afternoon when I drove by and saw the spot had been suddenly cleaned up and roped off with plastic chains, its occupant abruptly banished.

As I headed back to the in-laws with our take-out dinner, I stopped at a light on the frontage road. Another dude living outside was sitting there on the concrete ledge above the excavated lower deck, in the shade of the elevated upper deck, checking his phone on that perch above the rush hour traffic. He had a big placard with drawings of wolves and people with lycanthrope eyes, and a handle you could use to find him online. When I visited his Instagram feed the next morning, I found the journal of a man roaming a more savage and dangerous city, fighting baseball bat-wielding Neanderthals and wrestling with the descent into knowing delusion, illustrated with drawings of fangs and fur and human eyes gone feral.

Earlier that afternoon I had read a news story about an Austin start-up founded by an already-rich entrepreneur and a famous geneticist. The mission of Colossal Biosciences is something I can relate to—“to jumpstart nature’s ancestral heartbeat” and rewild the planet. The means they propose to use is pure science fiction—to bring back the wooly mammoth, hybridizing its DNA with living elephants and releasing the reborn creatures to roam the arctic tundra. The pitch argues this will prove the capacity of revived species to serve as agents of active restoration of a doomed ecosystem. You can’t deny the romance, and as a place for rich guys to invest the money they don’t know what to do with it’s got some swat. But the altruism they cloak themselves in dresses up a more conventionally libertarian approach, and the notion that technological innovation—human remixing of the evolutionary genetics of megafauna—is a more worthy investment than, say, reducing the human imprint on the planet.

Saturday morning I strapped my canoe to my truck and headed out before dawn to meet a group of University of Texas marine biologists and their families and put in right at the spot where I had seen that dude carrying his baby across the river the Sunday before—the same spot where they have been monitoring our unlikely urban eels. It was a beautiful morning there in the wild spillway of the dam, where the egrets were gathered waiting for breakfast to fall out from the bottom of Town Lake. An osprey announced its presence just as we were putting in, the first of many we would see over the course of the morning, and you could see the enthusiasm of the kids in the group before we even got in the boats.

It’s hard to really convey how wondrous it is that a place like this river exists where it does, a place where the authentically wild flourishes in the shadows of skyscrapers. To put your paddle in the water behind a bank and an office building, with the traffic driving by and the planes flying over, and see the fish darting in the shallows and the herons of every color flitting around you in the tall trees that grow in the floodplain. It’s easy to dive into the romantic as you soak it all in—my nephew certainly did as he stood in the boat and had the best vantage of all of us. But when you know more of the story of that river, you understand it’s a story of resilience.

We paddled the full “pristine” stretch of the river, and then some. It’s not Eden. The dams upriver began their daily release just as we set out, using the river to keep the air conditioners and Bitcoin mines and mammoth resurrection labs running, and the current brought the stuff that washes off the surface of the city. But even with the water up and the trash here and there, you could see the ease with which places like the waterways around which we build our cities can be allowed to find their way back to wild, making space for other species to share our habitat with us. It was especially evident in the spots where major creeks enter the river, intersections where biodiversity thrives and you can find the big fish and the big birds and the ripe-smelling dens of aquatic mammals.

At the mouth of Boggy Creek, a creek that is paved for much of its course through East Austin, we found a nice example of one of the fossils they used to call the devil’s toenail—a Cretaceous bivalve of the sort that’s pretty common in the local waterways. We got to talking with one of the more knowledgeable members of our group about where you can go to find fossilized shark teeth, including one spot where it’s not hard to find the remains of the Megaladon, which we also decided would make a great band name.

It reminded me of the public lecture I took my now-adult son to when he was my nephew’s age, the first of an ongoing series in which the natural sciences faculty of the University of Texas at Austin tries to share their work with the general public. The lecturer was Tim Rowe, a paleontologist who had the genius idea to use magnetic resonance imaging to take a fresh look at the bones of dinosaurs and better see their connections to living creatures. He explained the path of revelation that study took him on, as it showed the connection of dinosaurs to modern birds—especially the flightless birds of Pacific Oceania, birds that had evolved without predators until humans showed up in boats a lot like the ones we paddled downriver yesterday. Dinosaurs, in other words, didn’t really go extinct. They evolved. But they now were likely to really go extinct, as their habitat was destroyed by human sprawl and predation.

Maybe sending the millionaires into space isn’t a bad idea after all.

Further reading

For more on Austin’s wooly mammoth start-up, check out this piece at Culture Map Austin.

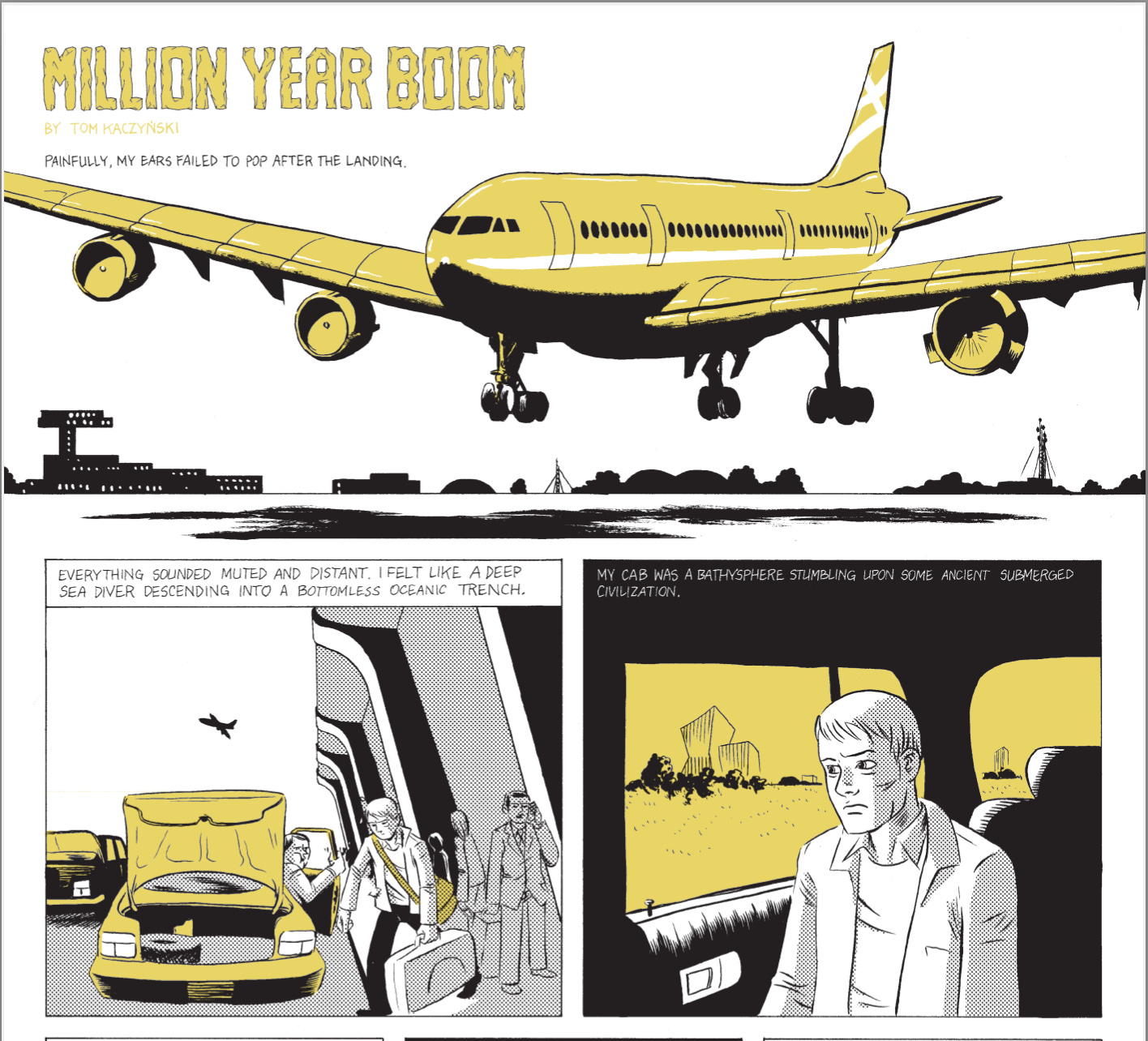

When I read the story of the start-up bros trying to bring back the wooly mammoth, I couldn't help but think I had read a prescient fictional variation of that story in one of the brilliant comics of Tom Kaczynski. His Eisner Award-nominated collection, Beta-Testing the Apocalypse, is coming out this fall in a new edition from Fantagraphics, which includes a foreword by me. It’s now available for preorder. Here’s the opening of “Million-Year Boom,” originally published way back in 2008 in Mome, about a guy who goes to work for a start-up that wants to use cutting-edge technology to rewild the human self:

For more on Austin’s place in Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, check out Michael Barnes’ 2019 reconsideration at the Austin American-Statesman.

For more about UT’s Ichthyology laboratory, check out their site, and this excellent profile of curator Dean Hendrickson, who organized yesterday’s paddle.

For a steady stream of urban eels, edgeland archaeology and other cool stuff, follow the Instagram feed of the amazing Holland Austin, aka @swampdogger, one of those guys who knows how to find the natural wonders hiding in plain sight.

More about paleontologist Tim Rowe here at the UT website, or check out his book on The Mistaken Extinction—Dinosaur Evolution and the Origin of Birds. Here’s an excerpt. See also Michael Novacek’s excellent Dinosaurs of the Flaming Cliffs, a compelling narrative of some of the related field work charged with a spirit of curious adventure.

The family-friendly public lectures program at which my son and I hard Professor Rowe continues as the Hot Science — Cool Talks program, and many of their lectures are now available online.

If you’re in Austin and want to paddle the urban river, you might talk to the folks at the Texas River School. And if you’re interested in river protection, please sign up to join our newsletter at the Colorado River Conservancy.

And if you want to hear me tell the story of how I ended up owing twenty bucks to Hunter S. Thompson, Lancer Kind managed to get it on tape in the latest installment of his four-part interview with me at his Sci-Fi Thoughts podcast.

Have a great week.

So rich as always, Chris. And I’ll definitely pop over to FantaGraphics and check out “Beta Testing…”

One of the co-founders of Colossal Biosciences is George Church. He’s been working in the wooly mammoth genome in his Harvard lab for years.

Unrelated to that, in the mid-2000s his research was funded by Jeffrey Epstein.