Love in the Ruins

Plus: A Cover Reveal (No. 148)

The coyotes were a little quieter this winter. I saw them often enough as the season ended, like the pair I spotted at the end of February moving through the downy brome in the empty lot next door, seemingly oblivious to the noise of the door factory cranking up for the day. They were on the trail of a trio of young deer I saw when I walked a little further, and for a moment I had a vantage that let me see both hunters and hunted when they could not see each other. Then they all disappeared into the woods before the story played out.

Sometimes on cold dark nights you’ll hear the hyena sounds of their mating season, a cacophony that can make you think there are a hundred coyotes out there even though it’s likely just a couple. Even crazier are the sounds the foxes make when their season arrives—more like human screams, from a canid that’s usually as quiet as a cat. When we hear them, it’s usually in the inky dark of the woods just beyond our fence, behind the industrial park. The first time you hear it, it’s horror movie scary. In time, it becomes a reassurance: that fur-bearing wild predators are still able to eke out an existence in the margins of the fastest-growing city in America. Even as the hordes of SXSW festival-goers fill the surrounding streets in search of the latest corporate simulation of Dionysian revel.

This is our fifteenth spring here in the brownfield we cleaned up and made our home. Every year feels more like a gift than the one before, because you know how hard the city is working to erase the wildness and put it to work. The more time passes, the more certain it seems that the empty lots and old factories will soon be bulldozed to make room for glass towers designed by spreadsheets, the kinds of buildings that remind you Capital has finally acquired the means of self-expression. Contracts are signed, millions are exchanged by electronic wire, and ownership is transferred on the official registry of human dominion over the land. Survey tags appear on low-hanging branches, grand plans are drawn, rezoning cases are heard. And somehow, the edgelands hold out for another season, in some spots becoming even wilder as the former industrial uses are abandoned before their replacements are ready to break ground. But we all know how that story ends. Even if the earth scientists have finally and officially declined to deem this age of human dominion the Anthropocene.

The ephemerality of nature’s gifts is especially felt in what passes for springtime in Texas, a moment of beauty amid the brutality that never ceases to generate raw wonder, even as it seems to get shorter every year. It comes at the end of a winter that only gets truly cold for a few nights, through which new plants visibly grow, and before the temperatures creep up into a long hot summer that lasts almost half the year. Every year, the beginning of spring is marked by the bloom of the spiderwort, an explosion of color in the gnarliest edges of the world we marred.

Our lot spent seven decades before us as the site through which a petroleum pipeline ran, at what was then the edge of town, and like many empty lots around here it was a popular place to dump trash. Epic kinds of trash—huge chunks of concrete busted up when some street or building was demolished to make room for the new. By the time we got here, most of it had been pushed to the edge of the lot, and half-buried in the loam of the hill that leads down to the wooded floodplain of the river. You can see it all through the soil—big Ozymandian remnants, and tiny grains of broken-down blocks mixed in with the soil. There, in the shade of the hackberrys at the edge of the woods, is where the spiderwort comes in wild and lush every February, with blossoms of fuchsia, veronica, and other rare purples, each of which only lasts a day.

There are 85 species of Tradescantia in the Linnaean taxonomy, 50 of which the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center counts in their regional database. The common name spiderwort comes from the viscous secretions of the long stem when cut, which harden into a web-like filament. Other popular names include inch plant, dayflower, and “wandering dude” (a recent replacement for a more offensive sectarian epithet invented by Christian settlers). All of the species of Trad. apparently have the ability to genetically mix, which may partly explain their capacity to thrive in the aftermath of our ruin. You can even find it growing in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, where a clone of Tradescantia is used as a living monitor of mutagens.

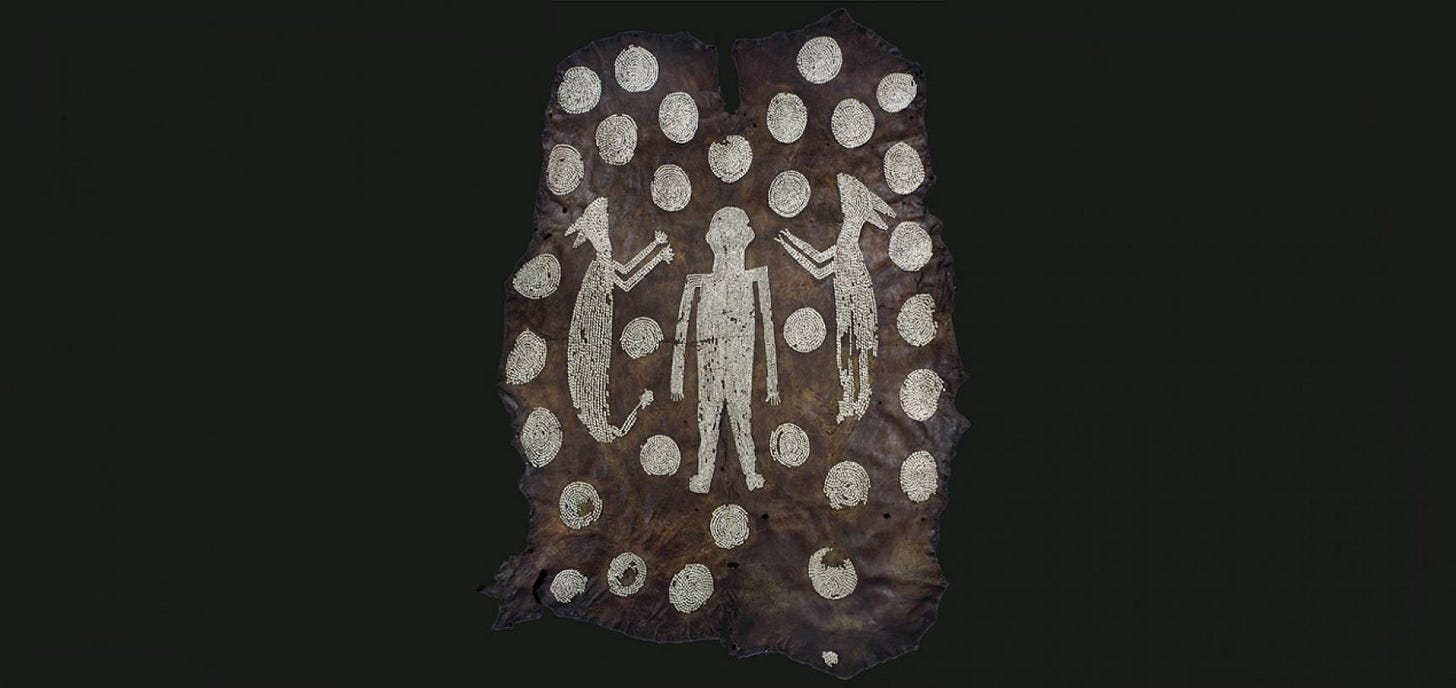

The scientific name of the plants is Linnaeus’ tribute to John Tradescant the Younger, the 17th century English botanist and royal gardener who, with his similarly employed father John Tradescant the Elder, brought many plants back to Britain from the colonies, including Tradescantia virginiana. The Younger also brought back other prizes from the New World, including the mantle of the Tsenacomoco chief Wahunsonacock, aka Powhatan, father of the woman known to the 17th Century English as Pocahontas.

Beginning in the 1630s, and continuing through the Civil War, Tradescant the Younger maintained what may have been the world’s first public museum at the family home in South Lambeth, in a building he called The Ark, a cabinet of curiosities comprised entirely of the natural history and anthropological wonders he and his father had collected. The entire catalog is available at the Internet Archive, and much of the collection can still be found at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, endowed by Elias Ashmole, who acquired the contents of the Musaeum Tradescantianum from Tradescant the Younger in, depending on which account you believe, a gift or a swindle.

I did not know that this magical object was there to be experienced during the year I spent studying down the street from the Ashmolean, reading Leszek Kolakowski and Max Weber in the P.P.E. reading room and switching to pints at the King’s Arms after the library closed. I have to settle for the image available online, but it still conveys some of the power and mystery of this relic of the peoples that lived here before us, and encodes some of the quantum of our erasure, and the closer connection those people had to the life around them.

I don’t know what name the Powhatan had for the plant we named after the dude who took his cape. But it’s safe to assume he had one, knew this plant, and probably knew more about its properties than we do, in the way of really knowing, different knowledge than the genetic science that lets us map its mutations in response to our environmental degradation. The Trad’s ability to endure what we have done to its native habitat and the linear connection it gives us to the past of the land is a rare gift, as is the window its technicolor morphings give us into the transecologically wild future that may yet be.

The ephemeral bloom at the edge of our yard will already be gone by the time you read this post, but it will never not come back, even if its colors may mutate into something weirder than we can imagine.

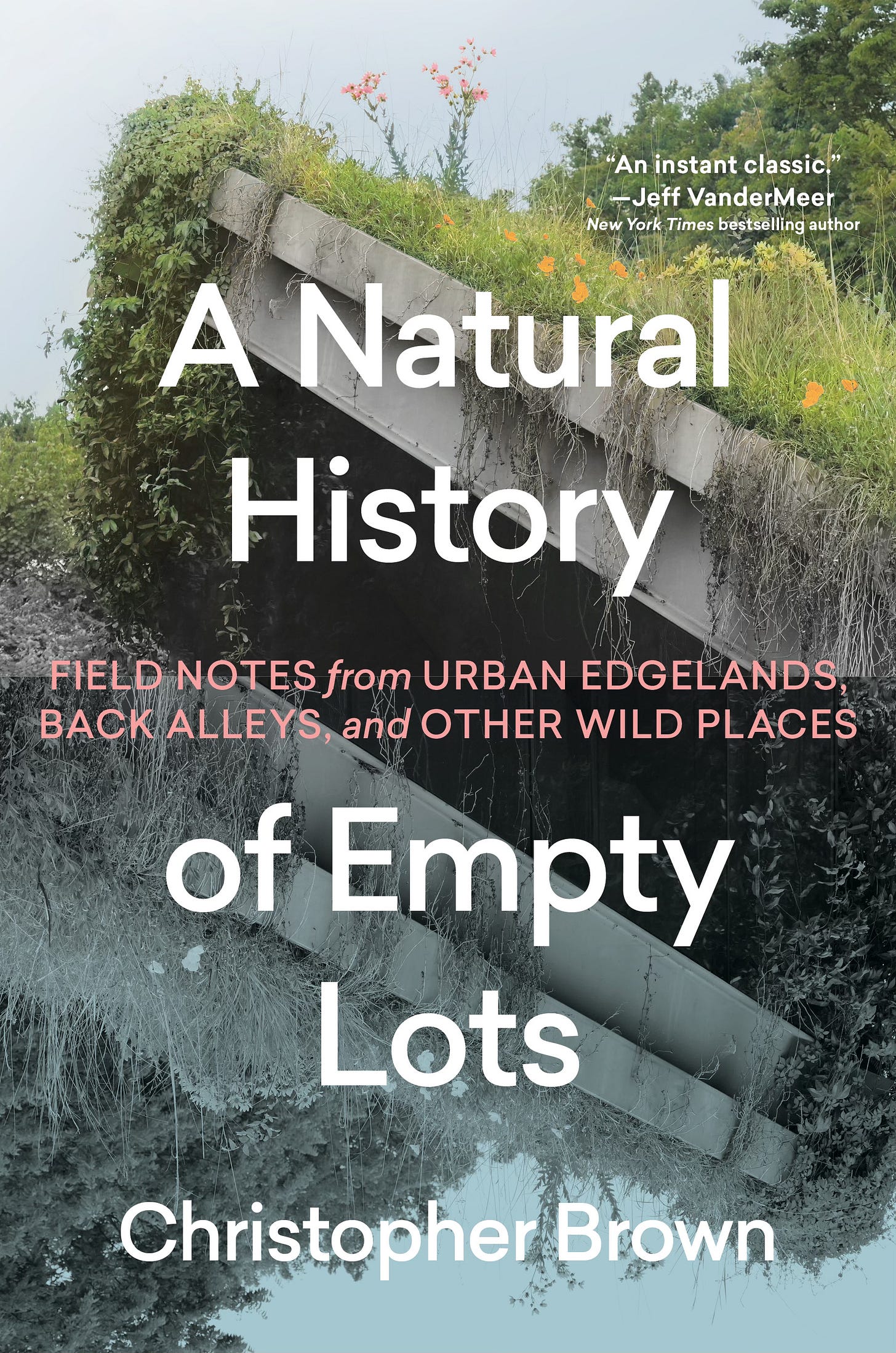

A Natural History of Empty Lots

Regular readers of this newsletter know that I have been working for the past couple of years on a book that draws from the same material as this newsletter—an exploration of how to find the wild city, and learn from it how to rewild everyday life. I’m pleased to finally be able to share the cover, which has gone live this week on the preorder pages:

The design is by Timber Press Creative Director Hillary Caudle, with input from my amazing editor Makenna Goodman, using a photo by me of the green roof of our feral little casa. Here’s their official description of the book:

A Natural History of Empty Lots is a genre-defying work of nature writing, literary nonfiction, and memoir that explores what happens when nature and the city intersect. To do this, we must challenge our assumptions of nature itself.

During the real estate crash of the late 2000s, Christopher Brown purchased an empty lot in an industrial section of Austin, Texas. The property—a brownfield site bisected with an abandoned petroleum pipeline and littered with concrete debris and landfill trash—was an unlikely site for a home. Along with his son, Brown had explored similar empty lots around Austin, so-called “ruined” spaces once used for agriculture and industry awaiting their redevelopment as Austin became a 21st century boom town. He discovered them to be teeming with natural activity, and embarked on a twenty-year project to live in and document such spaces. There, in our most damaged landscapes, he witnessed the remarkable resilience of wild nature, learned how easy it is to bring back the wild in our own backyards, and discovered that, by working to heal the wounds we have made on the Earth, we can also heal ourselves.

Beautifully written and philosophically hard-hitting, A Natural History of Empty Lots offers a new lens on human disruption and nature, offering a sense of hope among the edgelands.

And here’s what some of the early readers—generous colleagues who took the time out of busy schedules to read the final manuscript before galleys were even ready—had to say:

“A loving, deeply pleasurable, and sprawling investigation of place, community, personal history, and larger contexts. A Natural History of Empty Lots has the shape and liveliness of something organic, as if it has grown out of the neglected, teeming hidden places of the landscape Brown knows so well. An incredible book.”

— Kelly Link, Pulitzer finalist, MacArthur Fellow, and award-winning author of The Book of Love

“A Natural History of Empty Lots is the best and most interesting book I’ve ever read about the spaces we often overlook. Christopher Brown comes to these places with a deep curiosity and understanding of both human and nonhuman history. An instant classic.”

— Jeff VanderMeer, New York Times bestselling author of Annihilation

“Too often, what we call ‘nature writing’ is nostalgic for what never was. Thank goodness for Christopher Brown, who sees the wonder in what is and what might be. A Natural History of Empty Lots is the nature writing we need now.”

—Michelle Nijhuis, author of Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction

The book is structured in three parts. The first and longest section explores how to find the wild city—the interstitial wildernesses each city hides, and the animal and plant life that makes its home through—all through a lifetime of personal experiences of such discoveries. The second part talks about rewilding domestic life, through the prism of our own experiments in making a feral house. The final section distills some lessons from the first two to explore paths to rewild the self and society, and build a greener future.

If you enjoy this newsletter, I think you will dig this book. It took a lot of work to shape this material into a narrative form that does all the things I wanted it to (or at least, I hope, comes close), and I was lucky to find a partner in a publisher that got what I was trying to do and was willing to invest in it. It should be a beautiful book when that team is done producing it, with a hardcover print edition and twenty-some black and white interior photos (along with ebook and audio editions). If it sounds of interest, please consider pre-ordering a copy—doing so can have a big impact on how well the book launches when it is released on October 15 of this year.

You can preorder Empty Lots directly from Hachette, or from Bookshop, Austin’s BookPeople, IndieBound, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or your favorite local bookstore.

And just for fun, as an additional bonus incentive, if you preorder the book and let me know about it, I will send you a print version of this newsletter that I plan to make in connection with the publication—a newsletter like the ones that used to come in the mail, with photos, new material, and perhaps some material that didn’t make it into the final book. Maybe even a map to the places whose locations I deliberately obfuscate. If that sounds like your kind of thing, you can email me at chris@alexbrownfoundation.org—or just reply to this newsletter if you read it by email. Please include your mailing address unless you prefer a PDF, along with your preorder confirmation.

(Thanks to Field Notes friends Robin Sloan (Moonbound) and Ed Park (Same Bed Different Dreams) for the book-related zine inspiration, and for tolerating my appropriation of an idea worth stealing.)

Lastly, if you think it’s of interest, please consider sharing the info about the book with your friends.

In other news

I was moved by the obituary in last week’s NYT of Nancy Wallace, whose work beginning in the 1980s saved and helped rewild the Bronx River in New York City. If you can do it there, surely you can do it anywhere?

I was also sad to read earlier this year about the death of author Terry Bisson, who I had the good fortune to spend an evening with in 2019. Terry’s story “Bears Discover Fire” is a short-form masterpiece of ecology-focused fiction. And his work as an editor produced the remarkable Outspoken Authors series for PM Press, which I have promoted here before, featuring a mix of old and new material and a fresh interview with writers of innovative (and usually speculative) fiction.

I was happy to get my copy this week of one of Terry’s last books in the series, The Collapsing Frontier, which features the work of genre-buster Jonathan Lethem, including an especially engaging transcript of his conversation with Terry about his work and career.

Speaking of the Wildflower Center, Athena the Great Horned Owl is back at her roost above the entrance, and you can now invade her privacy right from your phone via this webcam:

Lastly, if you’re in Austin and care about the future of our city—including our non-human neighbors—I hope you will join me in supporting Carmen Llanes in her campaign for Mayor.

Have a great week, and don’t be afraid to practice a little Thoreauian civil disobedience over the beginning of Daylight Savings Time if, like us, you are one of its victims.

Always so encouraging to read about wild species ability to thrive alongside us if we give them half a chance. No coyotes in South London but we do have lots of foxes and I remember the shock of first hearing their very human sounding mating screams.

I'm interested to read your book, Christopher, as I'm collecting a specialist library of place writing.