Living in the Interzone

No. 126

“Alhena is an evolving star that is exhausting the supply of hydrogen at its core.”

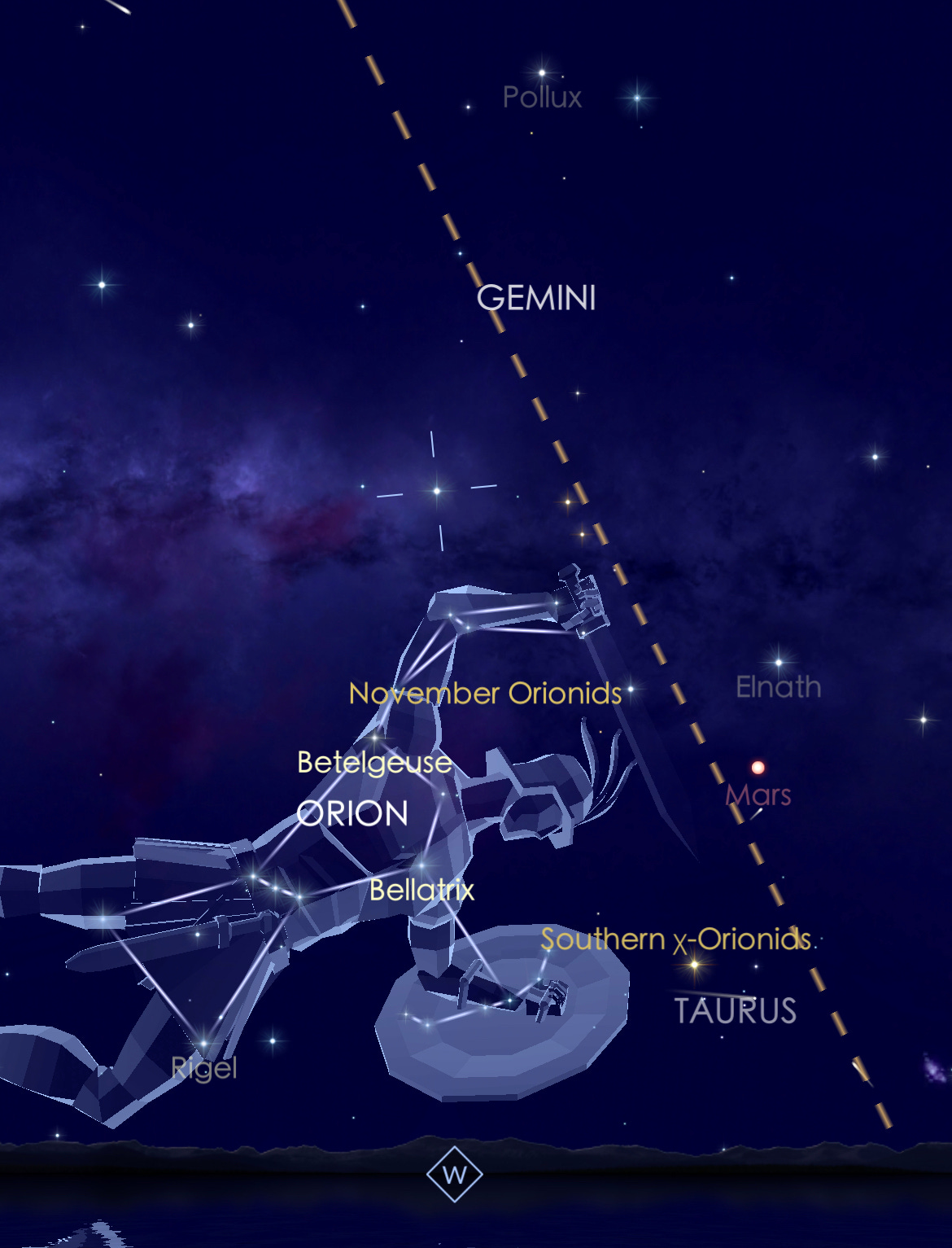

I saw it over downtown Thursday morning, a little before 5 a.m., shining so brightly that I wondered what planet it was. You could see Mars there in Taurus, surrounded by other stars that were similarly bright, on one of those cool and clear December nights when the moon sets some time after the bars close, and an early riser can see enough of the heavens to be reminded of the cosmic majesty we let our cities hide from us. But when I got to my trailer and looked up the objects I had just seen, I learned that Alhena, whose name comes from the Arabic word for the brand on the neck of a camel, is one of 85 stars in the constellation Gemini that the astronomical authorities say you can see with the naked eye. I saw three, even though it was as dark as it gets around here without a power outage. But I was still happy to learn that I had clearly seen the Zodiac twins of my astrological sign, which as a star-gazing boy I always had so much trouble finding that I gave up.

It’s hard to convey just how dark it feels here where we live, especially during the hours of the madrugada. The valley of the urban river is a streaming inkwell, thickly wooded on either side, and when you walk along its edges at a moonless hour, even though the nearby street lamps are still on, you can’t even see the ground beneath your feet, at least for the first few minutes until your eyes adjust. It’s a darkness that can scare you, even as you learn to cherish it—especially when you see the changes that are coming, as real estate capital imagines ways to transform the industrial edgeland into a new urbanist wonderland, one of those places the architects populate for the CGI pitch with a diverse cast of sims that want you to believe the life they are selling will make you happy. I wonder if their rendering programs have the means to show you the wild canids who will be displaced by the light and commotion.

Thursday night I encountered a free but perhaps not wild canid down along the train tracks at the west end of downtown, not far from the spot where I encountered my first urban coyote fifteen years ago. That area where the Missouri Pacific railroad crosses the river from South Austin and then winds around the urban center before turning north was still industrial back then, landmarked by municipal infrastructure that was obsolete but not yet replaced. The passenger rail station is still there, for those brave enough to endeavor the time travel that involves, but the power plant is now a mall with condos, and the water treatment plant whose empty pools my son and I used to explore has been replaced with gleaming towers of glass and steel. For those who measure the worth of land with spreadsheets, you can see it is an unqualified success, even though the only sign of nature along the pedestrian walkways is the distinct smell of animal urine one finds in those sorts of affluent and densely populated zones that have more dogs than children.

Dogs and droids. Thursday when I went to lunch I found myself being trailed by a little robot on wheels, who was learning to bring you the dinner you ordered from the app-connected ghost kitchen. The dog was trailed by a young field engineer on a scooter, wearing a yellow safety jersey and whispering training instructions to the bot. I watched as they navigated an unexpected obstacle—a car parked in the bike lane they were using. When I walked back, there they were again, headed the other direction.

There are still a few slivers of feral space in that zone. You can see the old man’s beard in bloom along the chain link that protects the freight trains from your trespass, and on the other side there is a stand of young retama that has grown up out of the ballast. Between the train tracks and the YMCA the woods are thicker, especially where the freeway onramp wraps it on the other side. I remember a December late in the dark years of the War on Terror when I came upon an encampment back in there that had been magically secured by its absent occupant with a criss-cross of fluorescent plastic string, the dangling hilt of a toy light saber, and a small picture of Santa Claus. The camps are cleared out now, but you can still find the trails.

If you look down, you might see the creek, where it widens out before feeding into the river. But the gleaming new buildings that tower over it work hard to keep your attention on them. From the outside, you can’t see how many of the office suites are empty.

Sunday afternoon my son and I put our canoe in a few miles down from the mouth of that creek. The rain clouds had finally cleared out, and the sun was full but the air still cool. The river was extra shallow, not just because the dam releases are mostly suspended during the winter. The sand from building all those new high-rises has accumulated in the riverbed, enough that not too long ago the owner of one of the local head shops, who has land on the river, won a Clean Water Act case against the city for its contribution to that. It wasn’t until I pulled my pictures off the card that I realized the mound this little blue heron was standing on was made from the plastic netting used to prevent erosion at construction sites.

There have been reports of bald eagles around here this season. A good friend reported seeing one Tuesday morning at a brownfield restoration site right across the river from us, and another friend said he’s heard of multiple sightings further down, in the direction of the Tesla plant. I haven’t seen one yet, but the knowledge that they are here is powerful affirmation of the habitat afforded by the stretch of the Lower Colorado that passes through the edgelands of East Austin. Eagles seem much warier of humans than other raptors. I wonder how long it will be before we crowd them back out.

We didn’t see any bald eagles Sunday, but we saw caracara, which look kind of like eagles with toupees, plus sky-dancing osprey, huge flocks of overwintering ducks, a ton of herons and egrets, and a steady flow of 737s coming and going from the nearby airport. The most curious bird was a presumably juvenile great blue flashing this strange pose in a tall tree behind an old aggregate mine just east of the tollway. Like some avian version of the gawky teenager you see trying to peacock at the mall.

When it got tired of voguing and took to the wing, erupting with that astonishingly loud squawk of the blue cranky, it was almost like it was molting back into the dinosaur form from which it descended. There are pterosaurs below the overpass, hiding in plain sight.

American scientists don’t call areas of urban wildlife like this edgelands. That’s an English term, coined by an ecologist with a sense of the romantic, and popularized by lyric poets looking for a way to explain the strange beauty of the industrial peripheries they spent their childhoods exploring. In the U.S., we don’t even really acknowledge these pockets of interstitial wilderness, even though they increasingly dominate our landscape, at least in terms of where the ecologically diverse activity is concentrated. We think of our nation as being divided between cities, agriculture, and major parks, the best of which we like to fool ourselves are perfectly preserved expanses of the wilderness we otherwise erased.

But when you dig into the contemporary literature of ecology, land use planning and disaster prevention, you learn that our patterns of continental occupation are dominated by a liminal wilderness dubbed the Wildland-Urban Interface (“WUI”). A term so bureaucratically stripped of any evocation of the character and feeling of such places, that you could reasonably (and probably rightly) believe it is designed to acknowledge the thing on the way to eradicating it. When it really encodes an acknowledgement that a large portion of the American population is living in close proximity to wild nature. And reveals the possibility that we could do so deliberately and harmoniously, instead of accidentally and in a constant state of conflict.

The WUI is mostly discussed from the perspective of fire policy and management, because in the western states it is where the fires happen, where settlement has pushed up against wild space. One in three American houses—44 million, occupied by almost 100 million people—are in the WUI (or were, as of the last big mapping exercise in 2010). I live there, and maybe you do, too. The largest concentrations are in states with lots of big urban areas that run up against and overlap with wild areas— Texas, North Carolina, Georgia and Pennsylvania, with California in the running. The lowest are in states that have a lot of mountain and desert and only a couple of big cities, like Wyoming and Utah, and zones of agricultural hegemony like Iowa, where I grew up, and Nebraska. The eastern states generally have more WUI than the west, being more densely settled without large chunks of public land.

The WUI is divided by the scientists who define it into two zones: (1) the Intermix communities, zones of more than 6.18 houses per square kilometer where more than 50% of the area is covered in woodland vegetation, and (2) the Interface, zones of more than 6.18 houses per square kilometer that have less than 50% vegetation cover but are within 2.4 kilometers of an area over 5 square km that is more than 75% vegetation. The kind of definition that is best expressed as a flowchart, but if you think about it, you know just the places they mean. (And you should know that the professionals who talk about the WUI tend to phonetically speak the acronym as “Wooeey”.)

The WUI has a higher likelihood of fire, more introduced invasive plants, more pets that disturb or prey on birds and other wild animals, and worse water quality due to runoff from pavement & lawns. It also has a higher potential for the experience of uncanny wonder. And while most of the scholarship of the WUI is focused on fire prevention, there is a rich emerging body of zoologically focused study, including of the ways animals interact with vehicular traffic, how our artificial light impacts their behavior, and how they develop networks for migration and habitation from the interstitial vegetated space we leave in the margins of our dominion. You can even find a Borgesian library of the things that can be learned from close observation of roadkill. In California, they have a crowdsourced Wikipedia version: the California Roadkill Observation System.

These morbid inventories of dead animals by the side of the road are the only real measure we seem to have of the wildlife that lives among us. It is much easier to count the canids that live in a national park than to conduct a census of the coyotes and foxes that live in empty lots, rights of way, railroad tracks, creek beds and pockets of woods between properties inside the urban fold. But buried within this strange bureaucratic compilation is the recognition that the real American wilderness is the compromised one we live in, or right next to. And if we could build a language that really acknowledged its existence, and maybe even evoked some of its dirty but indisputable beauty, we might be able to help it survive, and thrive. Maybe even in a way that more of us would get to experience its wonders in the fabric of our everyday lives.

Further Reading

The above notes on the Wildland-Urban Interface come from some of the research I’ve been doing for my forthcoming book The Secret History of Empty Lots, which has no pre-order page yet, but watch this space.

The first place Google will try to send you to if you look for the WUI is FEMA. The amazing 2010 map is available at the U.S. Forest Service, and there’s a more recent but harder to navigate online map at USGS. Many cities have adopted local versions of the 2015 Wildland-Urban Interface Code, and in Austin (and probably many other cities) they have mapped it.

Finding materials on the WUI that don’t relate to fire prevention is tougher, but if you have the patience to trawl through Google Scholar, you can find a lot of interesting stuff. Like Samantha Kreling, Kaitlyn Gaynor, and Courtney Coon’s 2019 study of “Roadkill distribution at the wildland-urban interface,” which focused on the ecology of an eight-lane stretch of I-280 in the Bay Area that runs between Los Altos and San Bruno, with heavily vegetated hills on one side and dense urban development on the other.

If you have the stomach for a deep dive into roadside ecology, the California Roadkill Observation System is a remarkable tool, and there is also a Maine Audubon Wildlife Road Watch. If you know of other such material, please let me know.

Last weekend we took my visiting mother to walk the wonders of McKinney Falls State Park in southeast Austin, a natural area which is very much in the WUI, and when one of the rangers read out my email address as I checked in, one of his colleagues announced she is a reader of this newsletter, and it was really wonderful to hear her explain it to him. Thanks to her, and to all of you who have shared this project with others who you think might like it.

Field Notes will be off next Sunday, in the field. Have a safe week.

I always enjoy reading your Field Notes and think your acknowledgment of the life in the edgelands lets us see our human selves in a different light. There is a sense of loss, but also of perseverance, of nature not giving in to our indifference. I live in a much different place; semi wild northern Texas Hill Country, where nature is still very close at hand. Even so, in the 40 years we've lived 20 miles from the closest town, development is happening everywhere. Land is being scraped, ranches are being subdivided and new subdivisions put in that use up our precious water resource, removing all the plant life but oaks. I try to focus on the beauty that's still here. Taking your example to guide me. Thank you.

First: thank you for “blue cranky,” the most accurate description of a blue heron I’ve seen. Cranky is likewise a good name for sandhill cranes. We’ve a lot of them here in south-central Michigan (even through winter, a sure sign of changing climate), and they have an inordinate amount of aggro for a bird their size.

Second: I live in the outer circle of residences surrounding a lake. Beyond me are farm fields and islands of woods. The diversity of wildlife around us is amazing, from prey to predator, from mice and moles and deer to coyotes, foxes, and owls (and sandhill cranes.) Your discussion about WIU made me consider what our local system looks like. There is a rumor that the field out back will be developed, adding another level to the residential ring around the lake. I wonder what the results will be.