In the Path of Totality

(No. 151)

Last Sunday morning the East Austin street retriever and I set out for a wander right at daybreak. It was still on the dark side, but I had a roll of low light tungsten film I was keen to try out, and the expectation based on two decades exploring these wild urban interzones that the crepuscular hour is when you are most likely to encounter the majesty of other species, and the wonders of the uncanny.

Our home is at the terminus of two little streets tucked behind a major throughway, in a neighborhood that was dominated by light industrial uses when we moved here fifteen years ago, and has showed a weird resistance to redevelopment, with many of the old properties evidencing a derelict inertia when the factory operators sell but the new owners can’t seem to turn the new urbanist utopias of their architectural renderings into glass and steel reality. Maybe it’s the dystopian novelist in me that likes the resulting sense of entropy. To be able to take a walk in a zone where the forward march of capital has run into some weirdly resistant force it cannot so easily break through, and wild nature finds room to express itself in the margins of our dominion.

If you walk straight south out of our back gate, you quickly enter a remarkable stretch of land no one owns. Accreted public land is the official designation—riparian bottoms exposed when the river shifted its course over the years, as it works its way from the last dam on the Colorado, at the eastern end of downtown Austin, toward Matagorda Bay. The idea that such ungoverned territory still exists, not in a remote Alaskan wilderness, but in the hidden margins of the fastest growing city in America, is a beautiful thing. If also an ephemeral one.

More typically, the empty lots behind the factories, warehouses and strip malls around here are owned but unmarked and untended, and bound up in a kind of developmental stasis by the things you would see if you looked at them through the eyes of a surveyor: unbuildable floodplains latticed with all manner of easements in favor of the legacy twentieth century infrastructure that followed either the course of the river or the paths of the old highways. Some of those old rights of way are little used these days, but remain public property, and through them you can trace a path of escape from the rules the city prescribes, if you know how to find the way.

Even when you have been exploring a zone like this for years, it changes so much week to week that the path is never the same. And the signs it leaves are often new and different. Last Sunday Lupe and I walked down the path of an abandoned old roadway, until we got to the spot where a gate was knocked down many years ago and has not been replaced. There’s a tiny grove right there in the trees by a drainage culvert where deer like to raise their young, and since winter the carcass of one adult female has been there in the grass. It’s just skeleton now, and after Lupe stopped to investigate it with her nose, she looked up at me, with “nope” in her eyes, and turned for home.

She’s 14 this year, so maybe she’s officially had enough with these walks into territories where her wild coyote cousins still hunt and kill their food. Or maybe the way the deer’s skull was now hanging on the fence post creeped her out. So I followed her home, let her in, and headed back out solo.

The zone behind the factories gets especially feral in spring, almost impassable in spots. You can see the traces of the paths made by deer and foxes, and you can follow them, if you accept the fact that you may need to crouch, or crawl, into foliage tunnels no biped has entered before. It’s a blessing that ticks are rare here, for reasons I have not yet divined. Chiggers are not, nor are snakes, but you learn to dress for both.

The red-shouldered hawks who nest in the riparian woods like to hunt from the tops of the telephone poles that mark one path through that zone, and sometimes when you break through the thickest patch of bramble and vine behind the construction supply warehouse, you will see one perched on the first pole at the corner of the wild field behind the dairy plant, or in one of the few trees that have been allowed to mature in that field in the four decades it served as a proprietary buffer between the factory and the adjacent wildlife sanctuary. But the plant was sold last year, and shuttered. The constant hum of the refrigerators is silenced, and you can hear things you didn’t hear before. Not just the cry of the hawk.

The invasive Johnson grass is coming up as always, but so are the native wildflowers, and the young mesquite trees that don’t know they are destined to be scraped from existence by the plow of the bulldozer. A bountiful crop of wild onions is in bloom, easily recognizable by their scallion stems. Wild edibles all. It made me wonder, if allowed to continue to naturally rewild like that, how long it would take for the native species to outcompete the invasives. But then I wonder whether any species that was here at the time of European settlement is really native to the climate that our factories and tollways have brought to our threshold.

As wild as the vegetation was, there were fewer signs of animal life than usual in that field. Maybe the change in the cover has changed their use. Or maybe they are as spooked by the sounds of human activity in the abandoned factory as I was. Metal banging somewhere on the other side of the fence. A car door slamming in the near distance. Murmuring voices. As I walked on, fresh tire tracks through the middle of the field, where the orange bracts of the castilleja were in bloom. Signs of urban scavengers seeing what things of value might be harvested from that old plant, out like I was when no one is around.

You might call them thieves, but I’m not sure how ethically distant they are from the private equity guys who bought the dairy company out of bankruptcy cheap so they could sell off the real estate. When the urban environmental justice groups I volunteer with held a press conference in front of the plant last year, trying to protect the preserve and the river from the proposed redevelopment, the workers came out to see what was going on. No one had told them the plant was for sale, and they would soon be out of work. The company had to call an emergency meeting. Maybe some of them are among the people sneaking through the hole in the back fence and salvaging what’s left before the demolition crews come.

I worked my way down toward the river, past the remnants of the camps that just got cleared out, and the new ones that just went up, walking through half-buried rubble illegally dumped there decades ago. The floodplain was verdant, but the bird life was more sparse. Some mornings it’s like that, and the pair of birders I saw on the high ridge of the opposite bank, binoculars aimed at the woods behind me, suggested there was more than I was seeing. But I found myself feeling that maybe the sense of anticipatory loss you develop as you see what the Chamber of Commerce has written for all undeveloped urban spaces has finally proven right.

The next morning, an armadillo met me on the path to our front door just before dawn, as I walked from the trailer I use as my home office to get ready for the official work week, and school for our daughter. It was foraging in the dirt, as they do, eaters of grubs. A big one, likely a male who keeps a burrow in our yard. They tend to keep several hideouts around the territory they feed from, so a safe escape from predation is always close by. They need to be able to escape from you fast, as armadillos rarely notice you until you are almost close enough to grab them. Then they lift their snouts up from the earth, visibly sniff and look, and turn and run with remarkable speed for carapace-armored little tanks.

You can see why the Aztecs called the animal the “turtle-rabbit,” Azotochtli.

It always pleases me to see a wild animal making home in our yard. We have worked to deliberately create habitat from this formerly polluted site, and it works, some seasons more vibrantly so than others. Armadillos may not be epic, but they have a trickster cool that entranced the local hippies enough to adopt them as their spirit animal back in the day. A familiar for Texas stoners, and, I thought in the moment, a modest indicator of ecological health. But then I found myself reminded of how even the dillos, who can do just fine in the zones we trashed, seem diminished by our domination of the landscape. An intuition unsupported by data that, while not “threatened,” they are not as common as they were even when I was a kid.

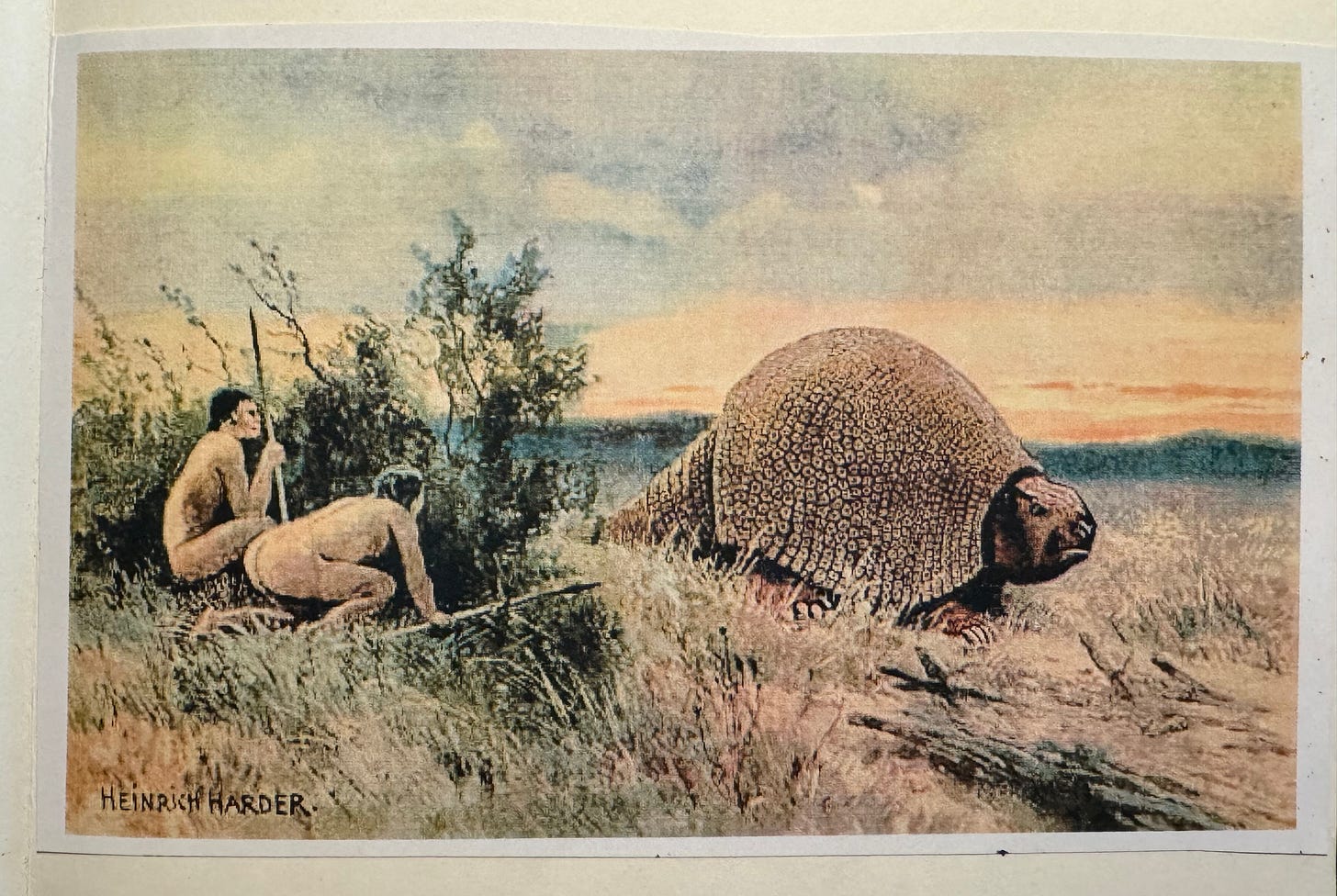

The natural historians surmise that prehistoric armadillos migrated into South America before the Isthmus of Panama submerged around 65 million years ago, and there diversified into an abundant variety of armored foragers. They were able to return to this continent in the late Pliocene, a few million years ago, and for a period they had that epic status—from Dasypus bellus, the “beautiful armadillo,” three times the size of of its contemporary cousins but otherwise largely identical, to the Glyptodons, who were the size of a car. We know how that turned out in the end.

By Friday, at the end of the work week, the town had filled with eclipse tourists. They all looked happy, enjoying the beautiful spring weather and Austin’s carefully constructed simulation of cool. I saw one blond young couple taking pictures of each other in front of a new condominium tower as if it were a cultural landmark, and three families getting a bicycle history tour of the zone of ahistorical colonial erasure through which they were riding. They all seemed to be looking up, as if waiting for the cosmic alignment we have all been told is coming. What meaning our collective subconscious expects to divine from the total eclipse of the sun is left mostly unexamined.

Many cultures, from the Incas to the ancient Greeks and modern era Transylvanians, have believed the eclipse to be a sign of the sun’s anger with humanity, or its sickness. Others, including pagan Germans, many West Africans and Native Americans, and the Tahitians, have told the story that the sun and moon were making love, in some cases more specifically that they turned the lights off while doing so.

I hoped there might be a similar variant among the Mayans. They had one deity whose name we do not know, called God L by the archaeologists, who was a Hades-like figure—a lecherous man with an armored cape and other features of an anthropomorphized armadillo, who dwells in the underworld and steals young women in horror stories paradoxically associated with the fertile gifts of spring. Those stories of the armadillo are connected by some in the codexes with stories of the sun making love to the moon, following a botched trick by the rain god. As for the portent to be divined from a solar eclipse, alas, the Mayans reportedly told us it means the moon is eating the sun.

The rain god appears likely to play another trick tomorrow, with thunderstorms in the forecast during the eclipse. My nephew, a seventh-grade nature lover with a wry sense of humor, has been following the forecast for three weeks and laughing as it gets ever cloudier.

We’ve had a generously rainy first quarter in this dry climate, and the signs of spring were especially bountiful in the weekend leading up to Monday’s long celestial minute. The butterflies were everywhere you looked Saturday—Nabokov’s beloved red admirals, all manner of skippers, and the first tangerine-colored Gulf fritillary of the year. It made me think their simple lessons might be more worthy of our attention than oracular events in the sky. Especially when I saw a red admiral wedged in the grill of my neighbor’s pickup the other day, and noted how rare it is to see such a thing these days. When I was a kid in the 70s, you couldn’t go for a road trip without your car being splattered with dozens of butterflies. A sign from the gods that should have all of our attention. Especially since we also have the power to remedy it, or at least ameliorate it, through the simple restorative act of making room for the wild.

Dillo Burrow Reading

Welcome and thanks to all the new subscribers to this newsletter. I started this in February of 2020, right after turning in the final edits to my last novel, and right before the pandemic overtook our world. A climate-focused science fiction writer and occasional essayist who also practices law, I wanted to experiment with a different sort of nature writing, one focused on urban wilderness and breaking through the illusory conceptions we often have that nature is a thing we must travel to find. I also wanted to show the ways I think we each have the power to help counter the horrific biodiversity crisis underway. The response has been great, and if you’re interested in checking out what’s come before, there’s a sampling of the most popular installments here. As a diary of wanders, the text sometimes does the same, so it may not be for everyone, but I hope you enjoy it and appreciate you checking it out.

I have been fortunate enough to now have a book coming out this fall, A Natural History of Empty Lots, that draws from the same material. “A genre-bending blend of naturalism, memoir, and social manifesto for rewilding the city, the self, and society,” as the publisher, Timber Press, describes it.

As previously mentioned here, as a preorder promotion I plan to do a print version of this newsletter with content not available elsewhere—outtakes from the book, both text and photos, entirely new material, and maybe even a map and some drawings. If you’re interested, just email me your preorder confirmation at chris@christopherbrown.com along with your preferred mailing address. Based on the response this far, I may do more than one print issue.

This week’s most sobering reading for me was the World Resource Institute’s latest Forest Pulse—the deeply researched inventory of the state of the world’s forests, with a particular emphasis on the loss of primary forest in tropical regions. While there’s evidence of progress, the rate of loss remains high.

For those who prefer to party through the end times, Austin Monthly has a great piece by Bryan Parker about the way locals are adapting to gentrification’s obliteration of cheap spaces to play by turning neighborhood convenience stores and even municipal drainage tunnels into venues for musical self-expression and communal celebration. One has to imagine similar underground scenes taking off in other cities overtaken by real estate capital. Thanks for the tip to Field Notes reader and friend Ed Cavazos, such a cool postcyberpunk dad that he brags about his son DJ’ing in the tunnel and on our nearby bridge on Saturday nights.

If you prefer your encounters with the wild to be by cathode ray, Criterion Channel has an awesome new collection up of Surreal Nature Films (including some creature features mixed in with the documentaries).

And for the Mayan variants on Isaiah Berlin’s business book-ready parable about the fox and the hedgehog, as well as the mysteries of God L, check out Sarah Newman and Franco Rossi’s “The Fox and the Armadillo: An Inquiry Into Classic Maya ‘Animal Categories,” from the May 2022 issue of Ancient Mesoamerica.

And if you’re in Austin and want a more progressive future for the city, drop by mayoral candidate Carmen Llanes’ rally this afternoon from 2-4 at Patterson Park, where she will be joined by Julie Oliver. Bonus: free eclipse glasses. Because who knows, the clouds might break.

Have a beautiful week.

.

I say ramble away … I for one will read about your rambles till the cows come home! Such an enjoyable start to the day. :)

outrageous green...