In search of the beached Impala

Wednesday morning I discovered my truck was being retaken by nature.

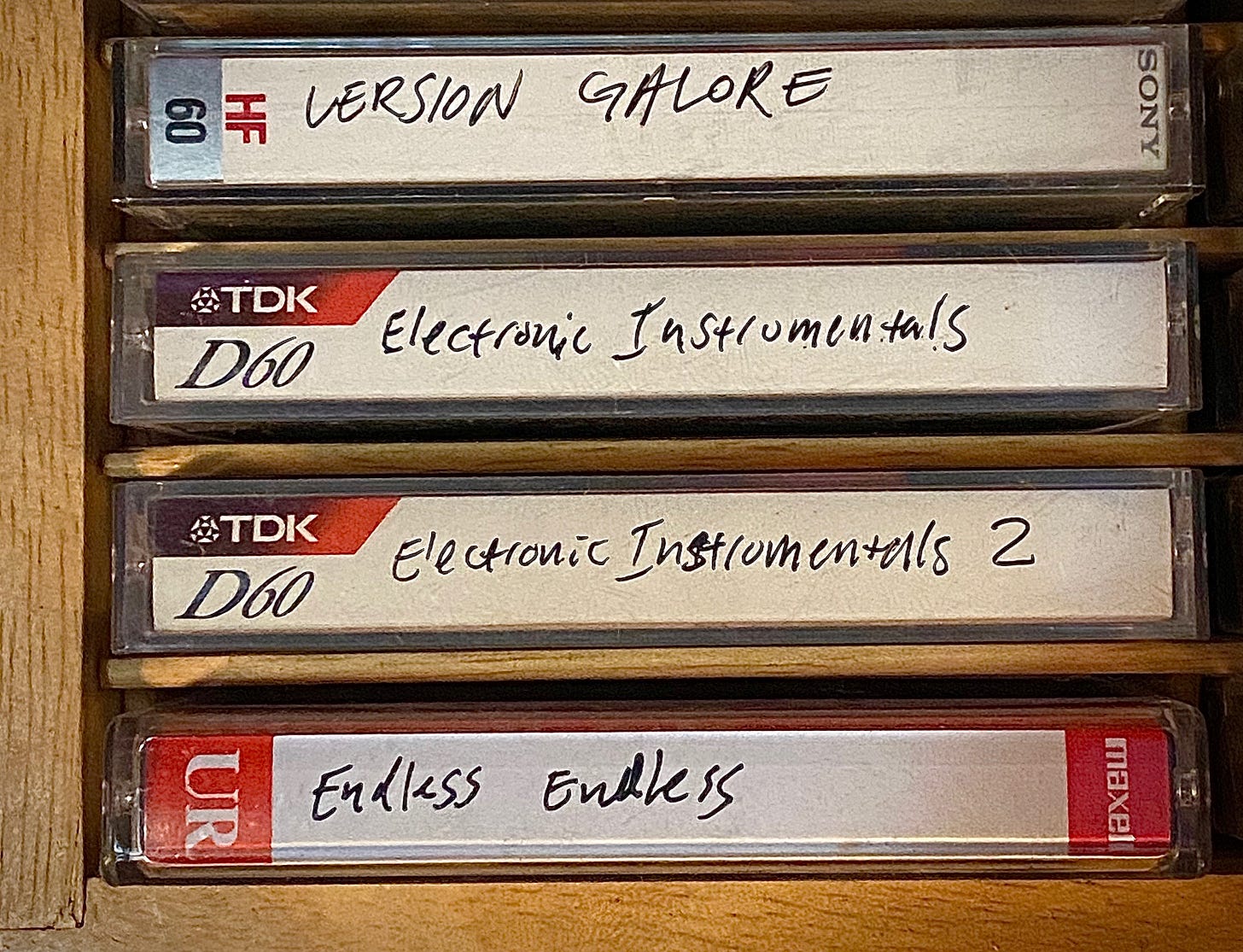

Like a lot of us, I haven’t driven much the past couple of months. When I do, it’s usually en famille, which means taking the newer and safer car. My ’87 Land Cruiser doesn’t even have proper seat belts in the back, and is not exactly suitable transportation for baby. Manual transmission, with a tape deck that still works, torn seats, analog radio, an engine that was also used in forklifts. To engage the four wheel drive, you have to get out and manually unlock the hubs—just the thing you want to do when you have found yourself bogged down in mud or snow.

It always starts (okay, almost always), even if you don’t drive it for weeks. And the tape deck still works, even if the Texas sun is as brutal on aged cassettes as it is on thirty-year-old paint.

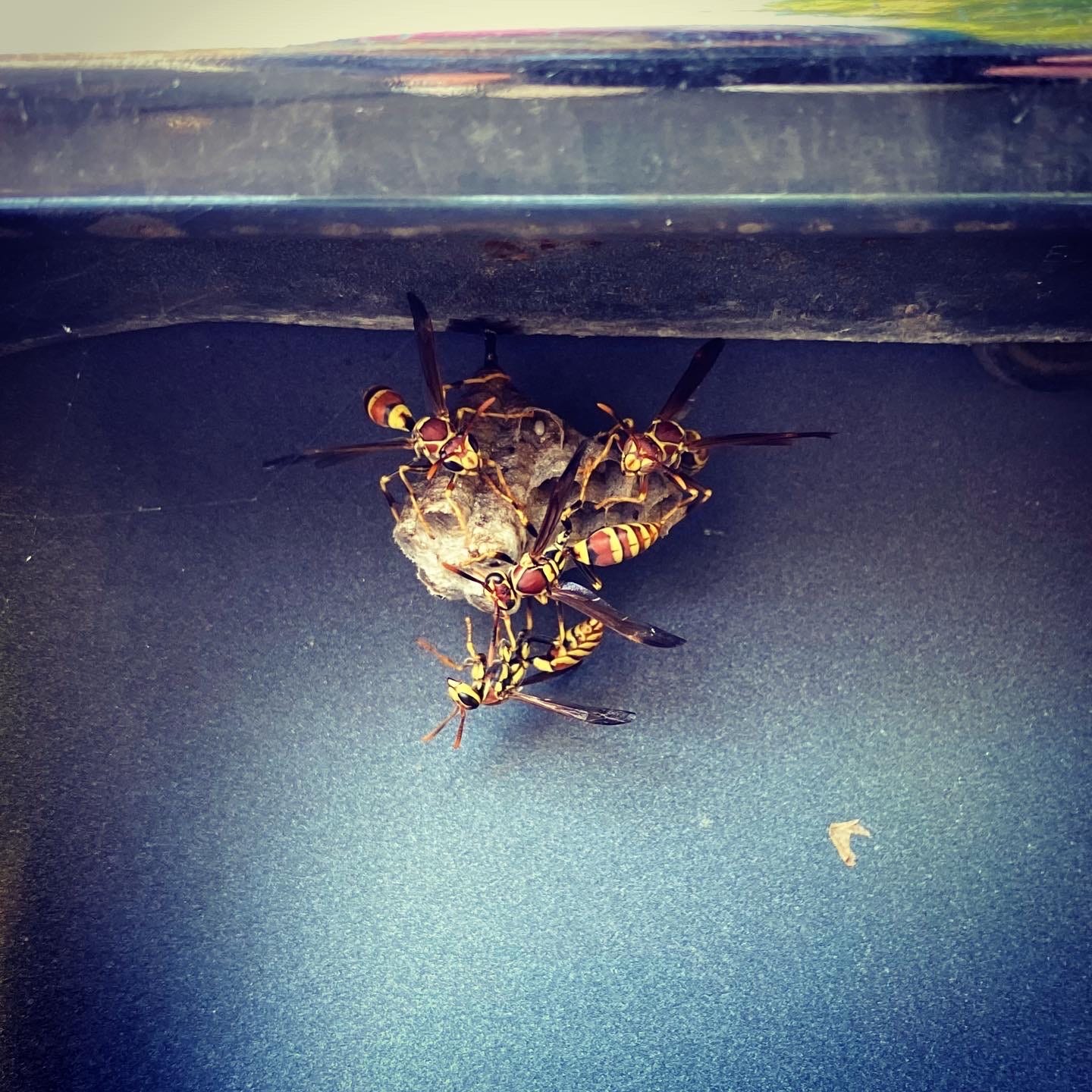

Wednesday I went out to look for something, and noticed a new spot on the rear lid, right by the handle. A little nest of yellowjackets, ready to go for a ride.

When we first moved over here, we lived for a couple of years in the rental next door. It was a little one-bedroom, an old house that had been moved here from some nicer part of town that got redeveloped. The side porch and our bedroom window looked out onto this “empty” lot. One morning I looked out and saw a flock of wild turkeys strutting. Another morning I woke to see dudes in blue hazmat suits digging around in our yard. They were supposed to be there—we had commissioned Chevron to remove the old petroleum pipeline that bisected the lot—but I hadn’t remembered they were coming that day until I rubbed my eyes and saw that surreal sight out the window.

One day the power went out and I went to check the circuit breaker on the side of the house. When I reached to open the cover, it felt like my hand was being tasered. A big nest of yellowjackets on the breaker box, who didn’t like me messing with their babies and let me know it. I had gotten plenty of honeybee stings as a kid, but never a wasp. I won, in the end, after I called in the air strike. But I learned to always look before I reach, especially on the outside of the house.

The yellowjackets, mud daubers, and other hornets and wasps love our house. The steel beams are perfect structures on which to hang their nests. In the spots where the beams are covered by hanging vines, even better. A motor vehicle seems a less likely place. But a few years ago, I had not driven the truck in a couple of months and found several chrysalises hanging from the wheels. And one morning I walked out there and found a freshly emerged Gulf fritillary butterfly.

The fritillaries like our chainlink fence, too.

Bats under bridges, cardinals making nests along our roofline from discarded packing materials, and butterflies on trucks. The capacity of all these supposedly simpler creatures to adapt to opportunities our habitat provides for shelter and survival are remarkable. I talk about looking for ways to actively promote such sharing of our space, but the truth they improvise surprising adaptations just fine without our help.

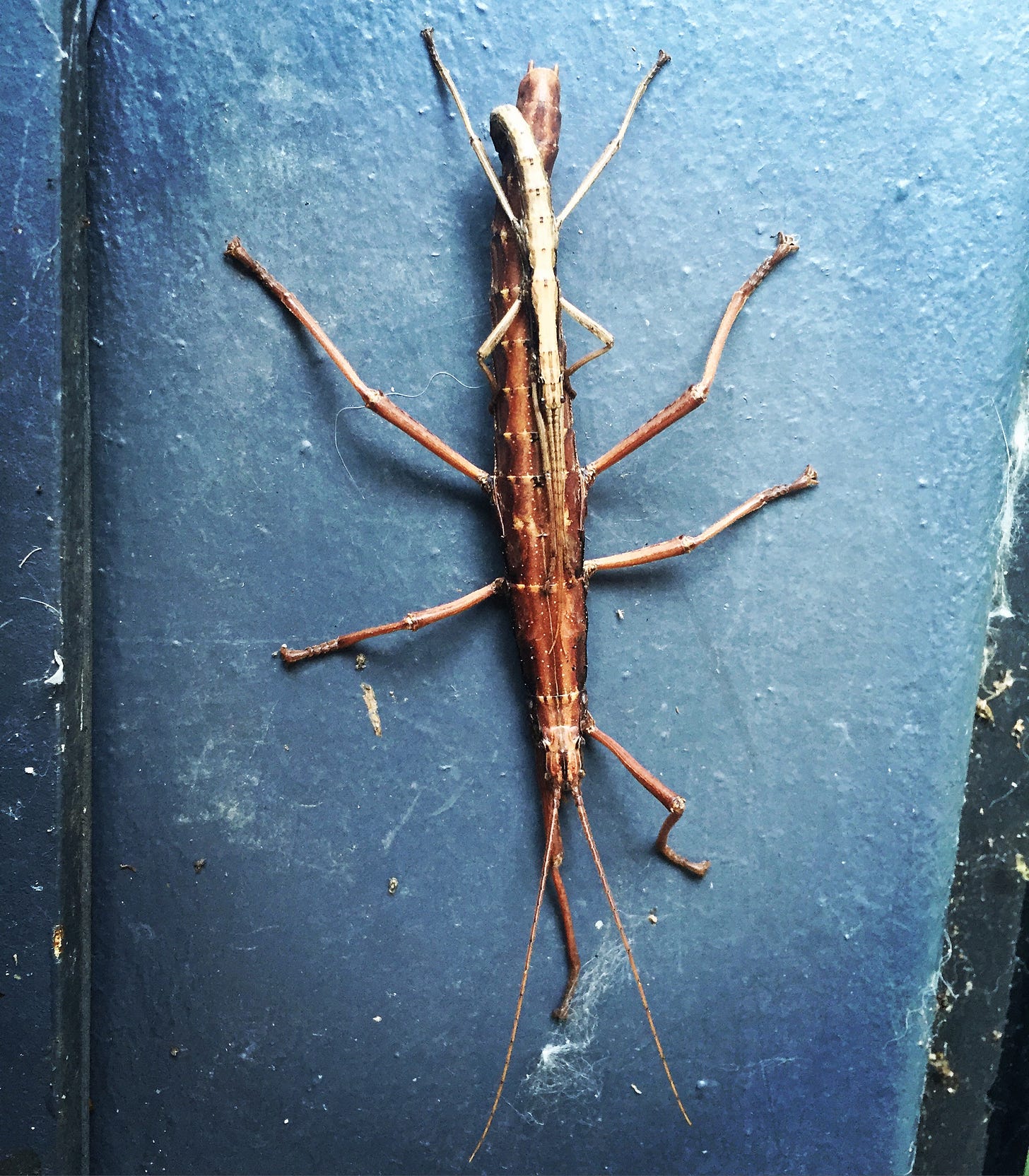

Our green roof brings the bugs, but what you wouldn’t expect is how the bugs love to hang out on those big sheets of window glazing. Especially after a rain. It’s an insect zoo, and a hall of mirrors. The grasshoppers are out there from spring to fall. Big mantises, chunky katydids, luminescent scarabs. The Texas walking sticks prefer the steel door frames, copulating for days and sometimes weeks, as the little males try to keep their competitors out until the babies are ready.

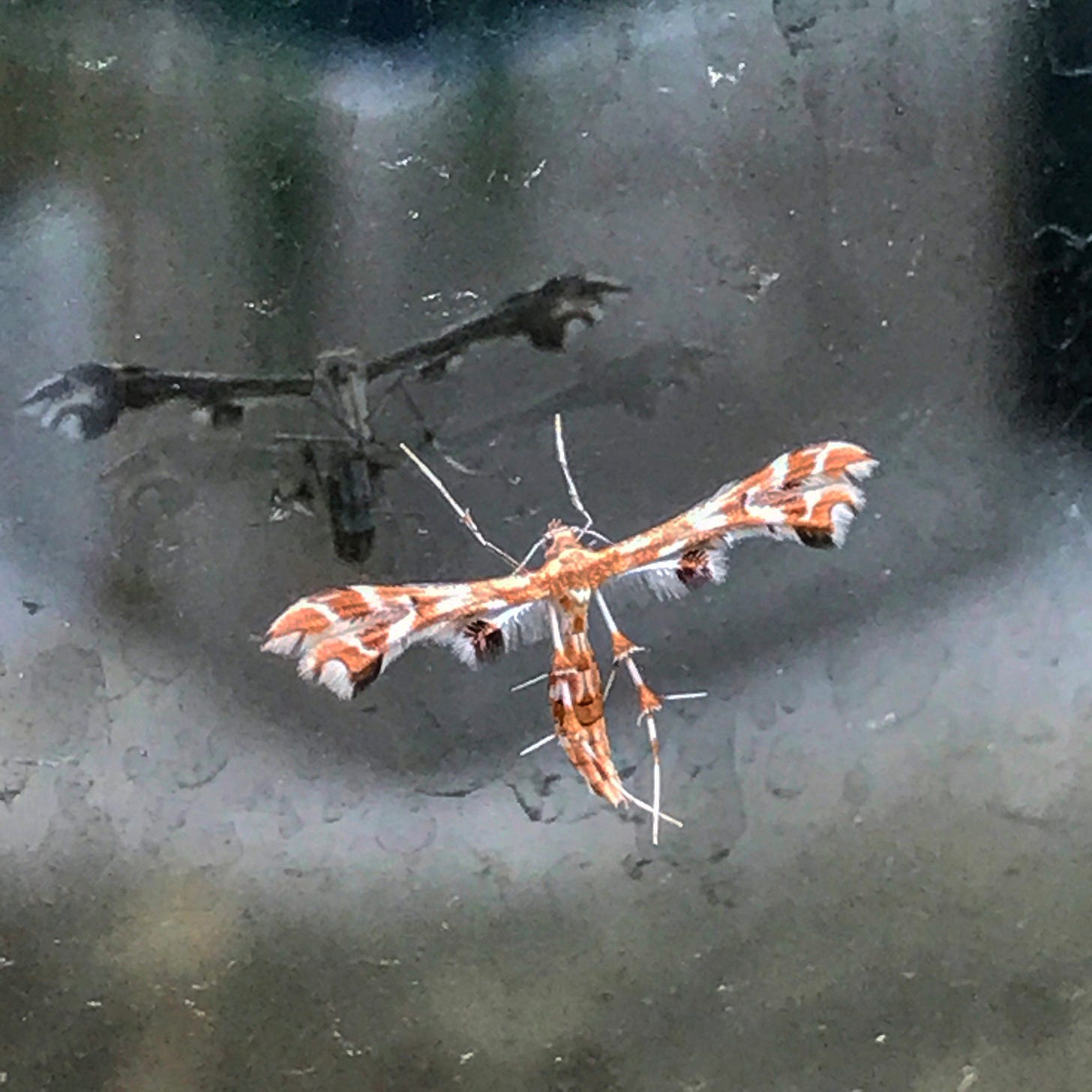

The coolest and weirdest bug I have seen in a decade here is the geranium plume moth I once found on the window. Pipe cleaners for wings, angular in weird ways, like the model for some tripped out Roger Dean flying machine on a 1970s prog album cover.

When the bugs are highlighted against such a clean surface, you can make out all sorts of details you wouldn’t otherwise notice. Often you see the imperfections. Battle scars of life lived. Evidence of the epic struggle and adaptation running through the trajectories of lives we consider short. I often see butterflies with big chunks missing from their rice paper wings, dusty colorings faded like the paint on my truck, and wonder what stories they harbor.

Often you’ll see a bug missing a limb, like this grasshopper I found on the door this week, limping its way through another Monday just like the rest of us.

They remind me of all the messed-up pigeons I used to see in the concrete jungles of my early adulthood, back in D.C. and New York. And then I think how most of us would look in middle age if we didn’t have access to things like cosmetic dentistry and orthopedic surgery. I, at least, would be half-toothless, bent, and limping.

We do see plenty of cars actually going back to nature. There’s an old Ford pickup that was here when we bought the lot, half buried in the bluff. Just the cab, with the front end ripped off, aimed at the sky like some dieselpunk space capsule. We kept it. It’s our edgeland gazebo, over by the grotto we made from the trash that had been dumped on the site over the years. It felt a little Cadillac Ranch at first, but now you don’t even notice it, the way the vegetation takes it over and hides it in plain sight. No wonder they can’t find all those lost cities of the Maya.

When you walk in the woods and along the river, you see lots of tires and car parts. There’s a big truck hood laying upside down in the shallow side pool I crossed with baby the other day. Sometimes you’ll be out on the river and you’ll see some strange thing creating its own weird current. You think it might be a dead animal until you stop and see it’s a big quarter panel.

Not long after we bought the lot, and I really started exploring this weird zone, I found the wreck that most epitomized the experience of the uncanny that this place conjures, an experience that was what started the first conversations between me and my wife back when we found ourselves neighbors on this odd little street. On the day we got married in 2013, I wrote an oblique ode to it on my old Tumblr, right after it had disappeared following a big flood:

Requiem for a Muscle Car

You could only find the Impala by accident. It was way off trail, in the back part of a wetland tucked between an urban river and the woods behind a bunch of light factories. They were the kind of woods and wetlands no one is really meant to explore, made from volunteer trees grown up between the chunks of concrete and demolition debris dumped in this downzoned stretch of interstitial wilderness at what once was the edge of town. The negative space of the metropolis, where nature fills in the gaps and wild animals feel free to roam in the absence of human gazes.

When you stumbled across it as you stepped out of the tall water grasses, it looked like it might have been there for thousands of years. But you also could remember when cars like that cruised the streets. Cars with Batmobile lines forged in a pre-apocalyptic Detroit. Cars whose profiles of postwar strength and Rust Belt wonder persist even as they weather into ruin. It was of that certain vintage, after the assassination of JFK and before the resignation of Nixon. Baked by the sun to primer working on gunmetal, with water plants growing up out of the seats and the engine block, guarded by the herons and egrets who filled the secret sanctuary of the wilderness hidden under the roar of the old highway.

You couldn’t tell how it had gotten there. It might have washed downriver in a big flood, or been driven down here at some time when the river channel was different. You would go back and look for it once in a while, and it was always there, but every time you went you needed to intuit a different path through the impassable wild vegetation and knee-sucking muck. It manifested different forms with the changes in the river, sometimes almost completely submerged, at other times almost ready to fly off with its steel hood extended like a gull wing. A mystical motorhead Ozymandias that transported you in ways its designers never intended.

It’s gone now, pulled out of the muck by newer machines dispatched by the stewards slowly working on cleaning up the edgeland and turning it into a park. Maybe they are right that it didn’t belong there with the birds and the fish and the native plants, so close to the “scenic overlook” that there was a real possibility some Audubon Society folks might see it. But it sure seemed like an indigenous expression to you, an artifact that perfectly expressed the essence of this place. You can still find its digital ghosts, if you know the right place to look on the omniscient maps, but that won’t last long.

Curiously, I found love tracking metal Impalas in these uncanny wetlands, another wanderer tuned into the strange vortex of surreal power of the Zona. She was making the wind dance in the windows of an old concrete fire tower while I was paddling against the current in a river out of time. That was five years ago. Yesterday we got married, and today we’ll celebrate with family and friends in this place we ended up making our home. The relics will come and go, but the wonder is always there if you can open up your third eye to it. The power is inside us, and especially poderoso now that we have a pair of magic rings to knock together. Our love is about a lot more than place, but the way we met is what set us on course into the uncharted territories ahead. It’s pretty awesome.

Today is Mother’s Day. The first one she gets to celebrate, and be celebrated, as an actual mother. Right after we celebrate baby’s first birthday. I don’t know how many beautiful ruins baby will get to see here, or how long we will even stay in this place. But the immediacy of urban nature here has reacquainted me with the ways new life and springtime go together, even when you have to build your nest on a piece of old steel. And taught me that even the steel machines we make to rule the plains will sink back into the swamp sooner than you think, like the fossils they burn in their engines. And like us.

When I see how those things go together, how the remaindered hulks of our civilization can shelter the creatures we share our domain with, especially as we learn that maybe we don’t need to drive our machines every day to get through life, it makes me a little more hopeful that the future for baby and her big brother and sister-in-law and sweet cousins and all her future friends may be a little healthier than I thought when we found she was on her way here.

For further reading on more hopeful futures, check out this piece by the science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson in The New Yorker, exploring how the pandemic has broken open the parameters of the possible in a way that creates new opportunities to imagine better tomorrows.

And if you want more like that, check out Robinson’s novels. My favorite may be one of his earliest, the plausibly ecotopian Pacific Edge, about a small California community trying to build a good life in the ruins of the world we left them. I re-read the book year before last, and it holds up remarkably well.

“The Coronavirus and Our Future” — Kim Stanley Robinson, The New Yorker, May 1, 2020

I was sorry to read of the death of Kraftwerk co-founder Florian Schneider this week. Techno music and nature walks may seem incongruous, but I have been thinking a lot lately about how you can feel the long echoes of German Romanticism in their work and many other “Krautrock” combos of that era. I hear it especially in Kraftwerk’s early albums Autobahn and Radioactivity, a harmonizing of the analog beauties of nature with the much darker “Romanticism made of steel” whose horrific legacies the German youth of the 70s were trying to come to terms with.

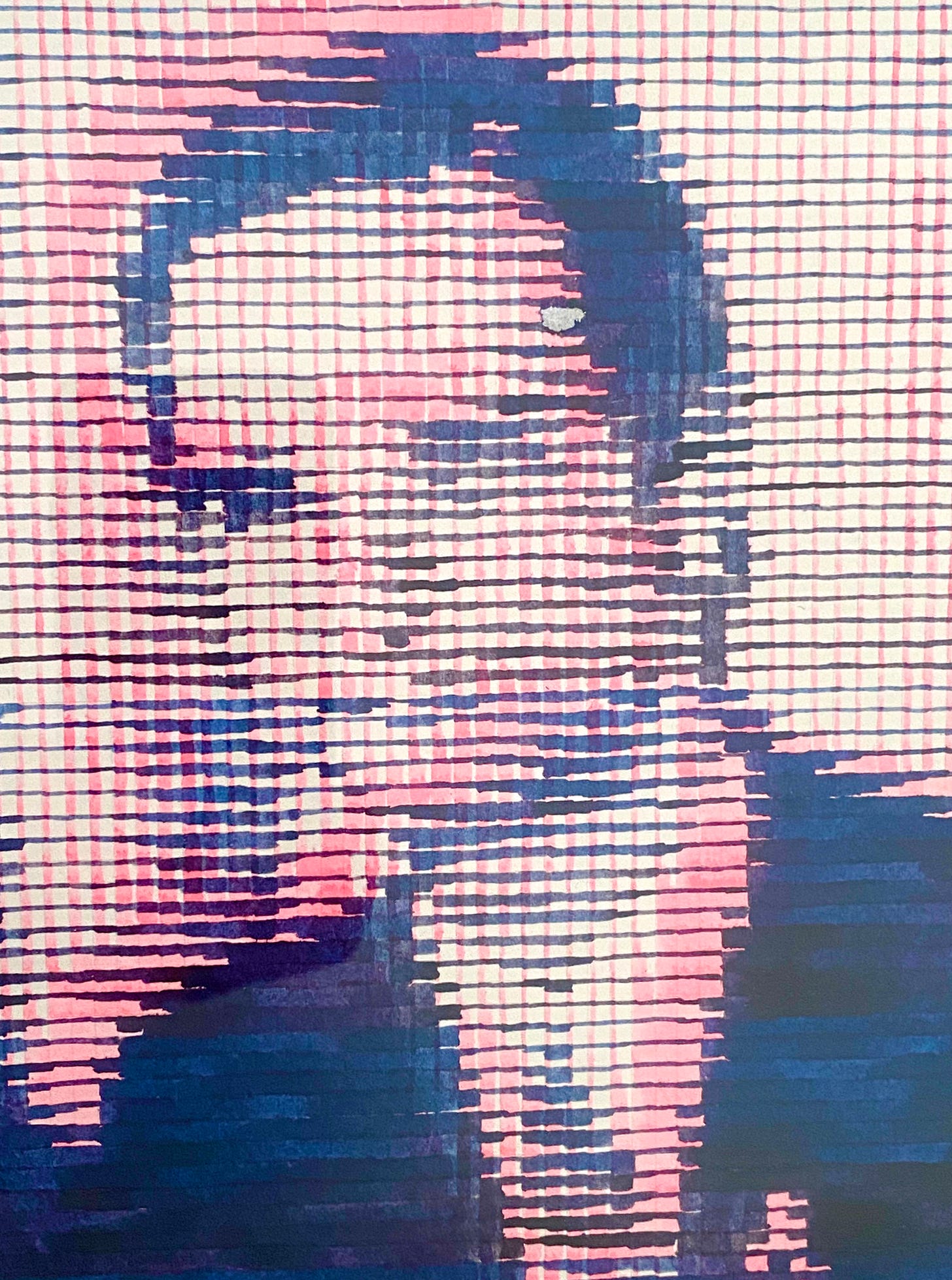

When we were kids, the title track from Autobahn was a big radio hit, back in an era when FM DJs could get away with playing 23-minute tracks with German lyrics. Our dad even had the 8-track in his car. Their music stuck with us, maybe because of the way it engages with the ambiguity of memory and experience without fighting to resolve it. Some of the last mixtapes my brother sent me to play in my truck before he died are full of early Kraftwerk, in a few cases remixed by him. The photo above shows Schneider’s portrait in a detail from an untitled work on paper Alex gave us a year or two before he died.

The coolest and maybe most under-appreciated thing about Florian Schneider is that he played the flute, and then threw it away. That’s him at the beginning of what in my mind is their first song, Morgenspaziergang, tuning in the sound of the birds you hear on a morning walk, which is what “Morgenspaziergang” means. When I finally get back in my truck, I will probably play that tape for the wasps and see if they like it. Though I think they are probably a little more metal.

Last bit: Searching the photo files for today’s Field Notes, I came across this mysterious thing I found in the yard around this time in 2016. It reminded me of a line from my favorite Houston surrealist, Donald Barthelme:

“The aim of literature…is the creation of a strange object covered with fur which breaks your heart.”

Have a safe week, and keep an eye out for strange objects.

Great pictures and descriptions. I love this sentence, "The relics will come and go, but the wonder is always there if you can open up your third eye to it." Very well said.