How to canoe pole the information superhighway

(with whitetails and coral snakes)

Monday morning we came upon a couple of young whitetail crossing the river at Secret Beach, just after sunup as baby and I were walking the dogs. It’s a pretty common sight to see around here, but always uplifting.

The first time I set out solo in a canoe on this stretch of river, long before I ever had the idea of living over here, I had one of those sightings. I had put in under the bridge, on a foggy Saturday morning, and as I paddled upriver around the first bend there were three deer crossing in the mist. Whitetail deer have a grace in shallow water that is almost equal to the leggy herons and egrets who spend most of their time there. And if you see them before they see you, it’s momentarily transportive. Not just into the unexpected stillness in the heart of the city, with the noise of the jets and trucks in the background. They take you out of time, helping you see the trackways of migratory megafauna that were here before, moving through continental space with no borders other than the ones the land and floodwaters make.

When the river floods for a prolonged period, you get a sense of how limited the range is for urban deer. When the water is too deep and fast for them to cross, and the whole wide floodplain fills, they become constrained to a narrow band of land between the fencelines behind the factories and the high water mark at the base of the bluff. You wonder if their ancestors were more wide-ranging. The buffalo we exterminated certainly were.

Maybe it’s because they are smaller than the whitetail, and more able to permeate our enclosures, that so many other species seem so good at finding pathways through the labyrinthine partitions we impose on the city. All along the fencelines behind the factories are the spots where little trails from the cover of the woods pass through well-worn passages under the bent back chain link, into urban space. We often see foxes trotting down our street under the lamps, until they disappear through the gap in the gate that leads to the empty lot where the street ends. The raccoons and opossums are even better-adapted, sneaking out to display their ability at getting the bungee cords off trash bins. And the coyotes let you know how widely they range, as they call out to the police sirens at night, and leave their tracks through the construction zones.

Many of the animals one sees around here are relatively recent arrivals, species the field guides don’t recognize as being from this region. The osprey that are so common on the river are a coastal bird according to Alsop’s handbook, and a species that was devastated by DDT. We’ve had a golden-cheeked warbler fly right up to our pool, flocks of white pelicans, and wood ducks on the urban floodwaters.

A couple of years ago I came upon what appeared to be alligator tracks along the river, in one of the spots I regularly walk. Something that’s common in the bayous near the coast, but exceptionally rare here.

Sometimes they are lost, like the white wagtail the birders have been spotting nearby this season, a bird they speculate got lost on its way home to the stretch that connects Siberia with the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. More often, they are finding their way to fresh food. Some of them fighting over our leftovers, but most of them feeding off each other or wild plants in the stretches of habitat the city will afford them. We are meant to roam, too. But the systems we have developed to feed ourselves and accumulate surpluses work better when we stay in place and work for those systems, hustling as hard as we can on capital’s treadmill.

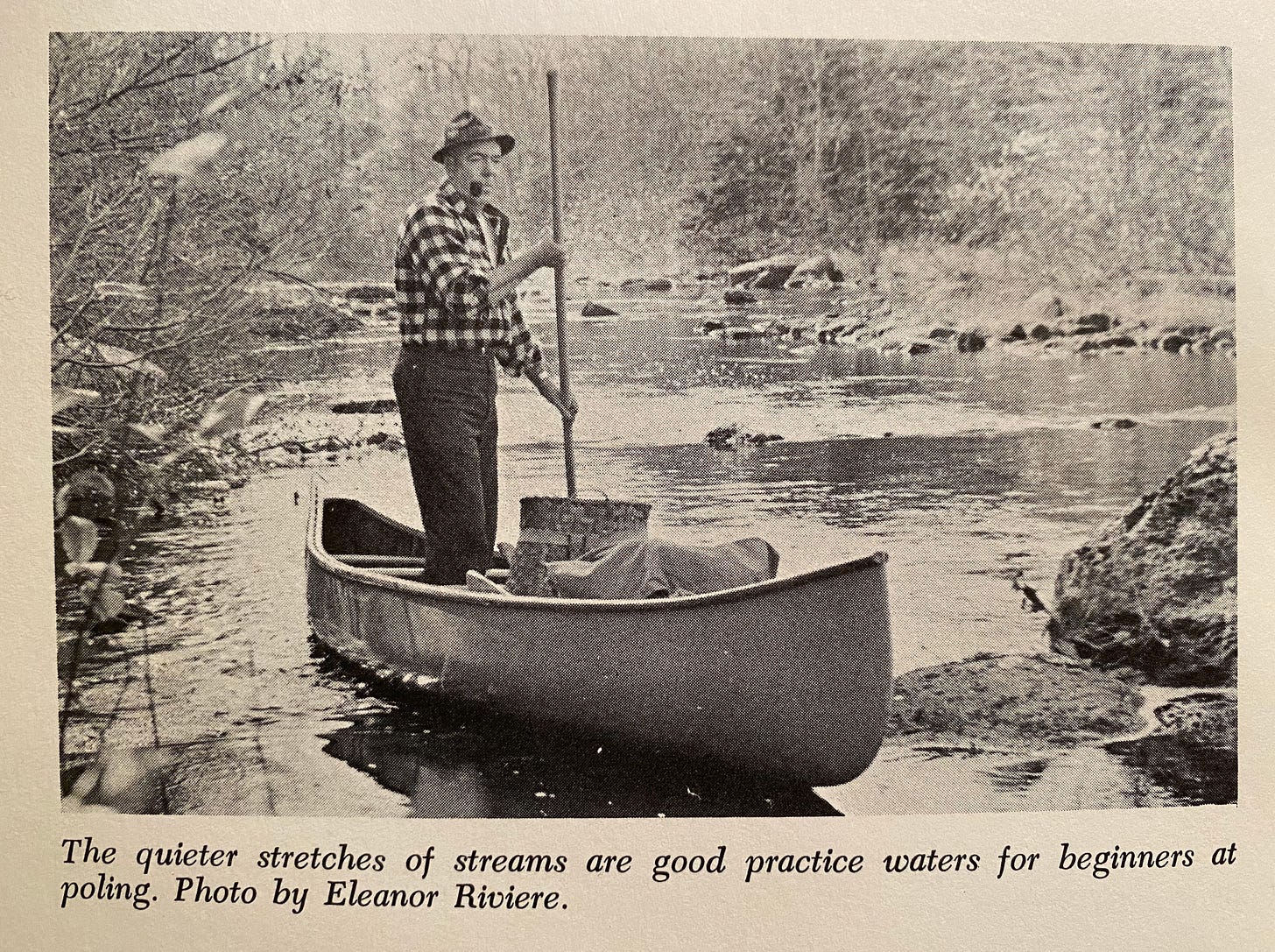

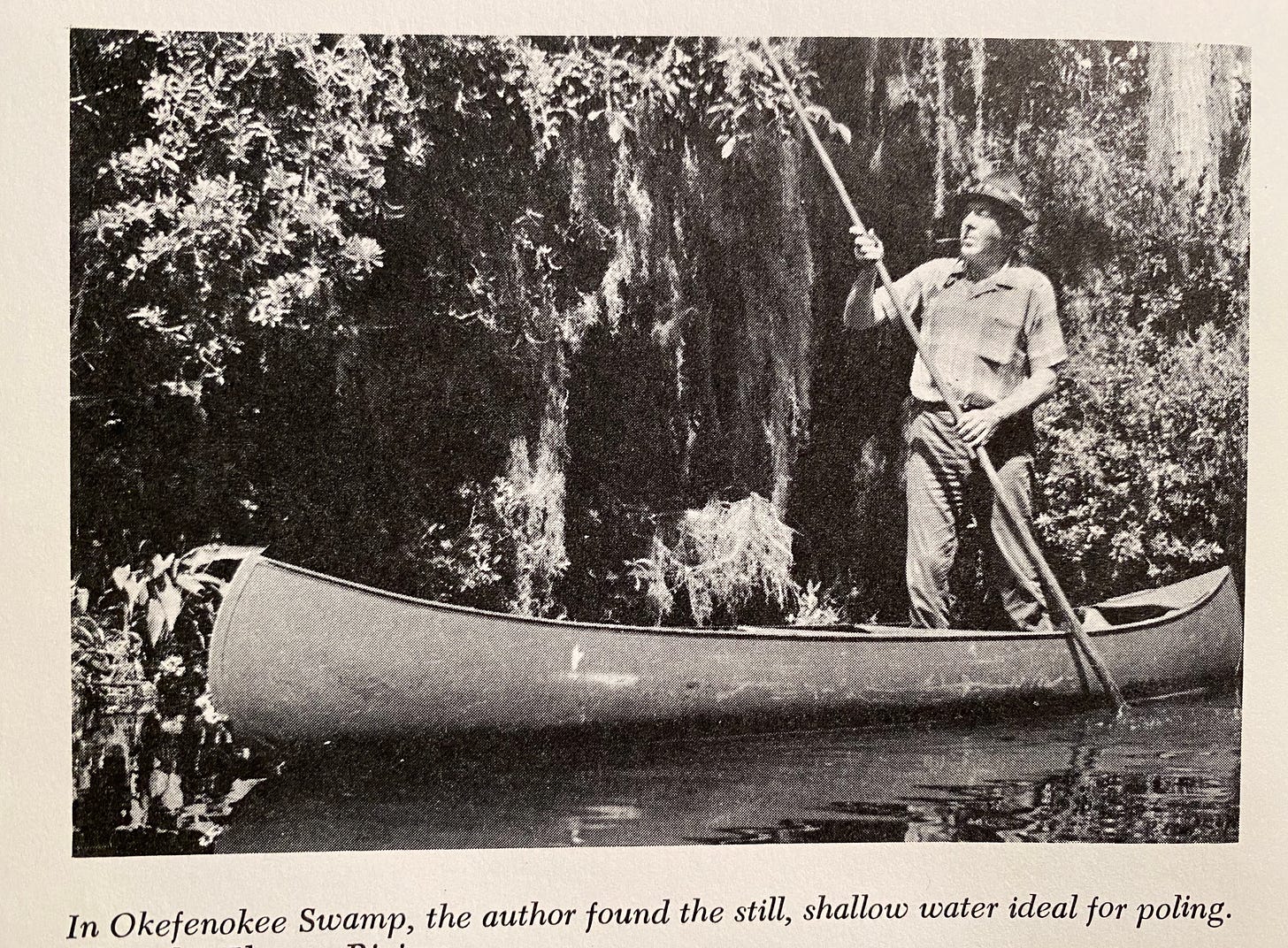

I am not as good as my neighbors at foraging for wild food, but I am pretty good at foraging for used books. And when my son’s passage through Cub Scouts helped me rediscover the joy of canoeing, as a way of exercising that urge to roam that is uniquely well-suited to the American landscape, I did a fair bit of trawling for vintage canoe books. Stories of big trips, and how-to guides. They usually feature action photos of the authors, like the above pic of Maine Border Patrol officer and Better Camping columnist Bill Riviere from his book Pole, Paddle and Portage, which first gave me the idea to try propelling my canoe like those punts I used to see in Oxford.

One of the first things you are taught when you get in the boat as a kid is don’t stand up in a canoe. But like most sensible rules, that is meant to be broken. Because if you stand up in a canoe, especially in fresh shallow water like we have on most of the rivers of Texas, you can suddenly see what’s going on under the water. You connect more closely with the river and the boat, as you balance your way through the flow. And you can go upriver, even through fast water.

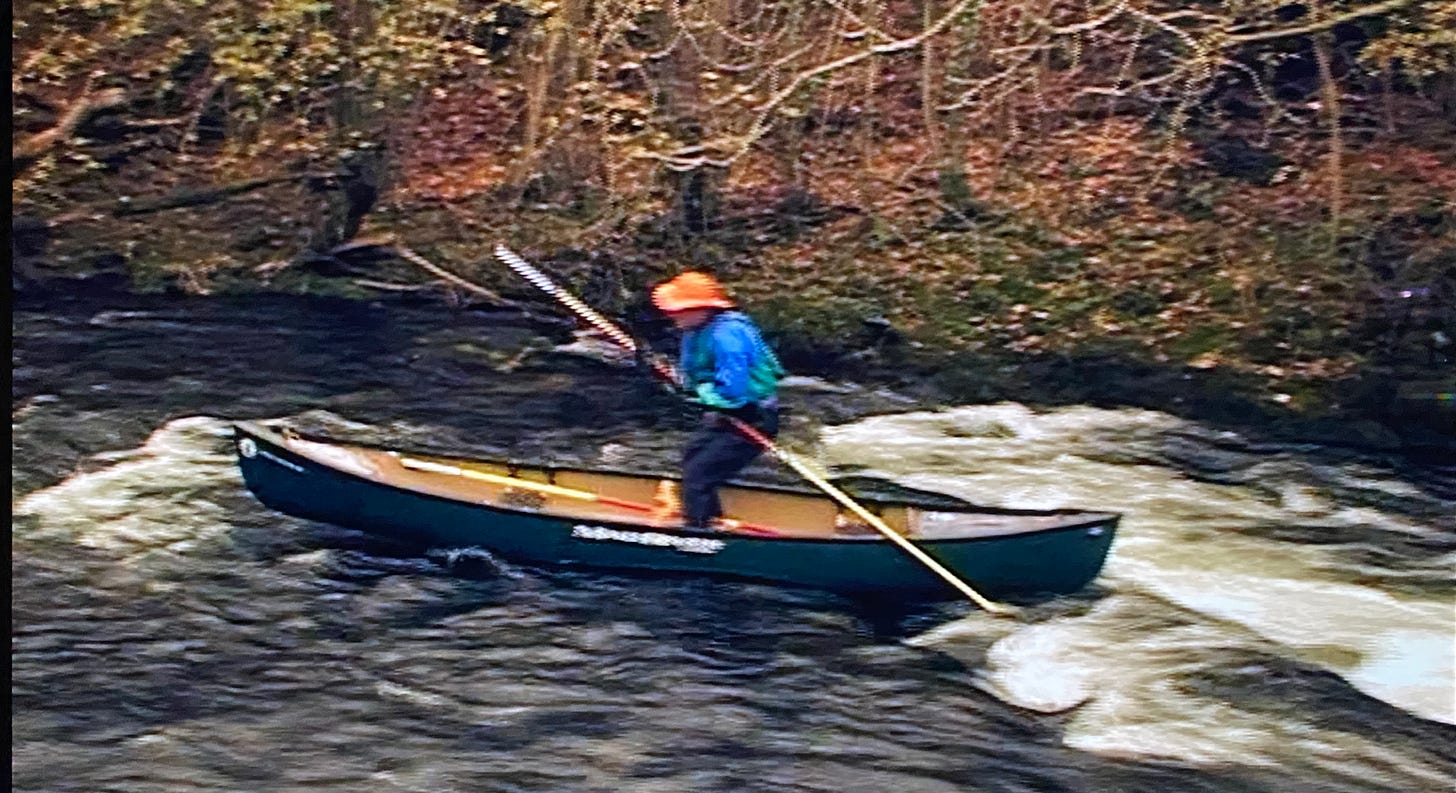

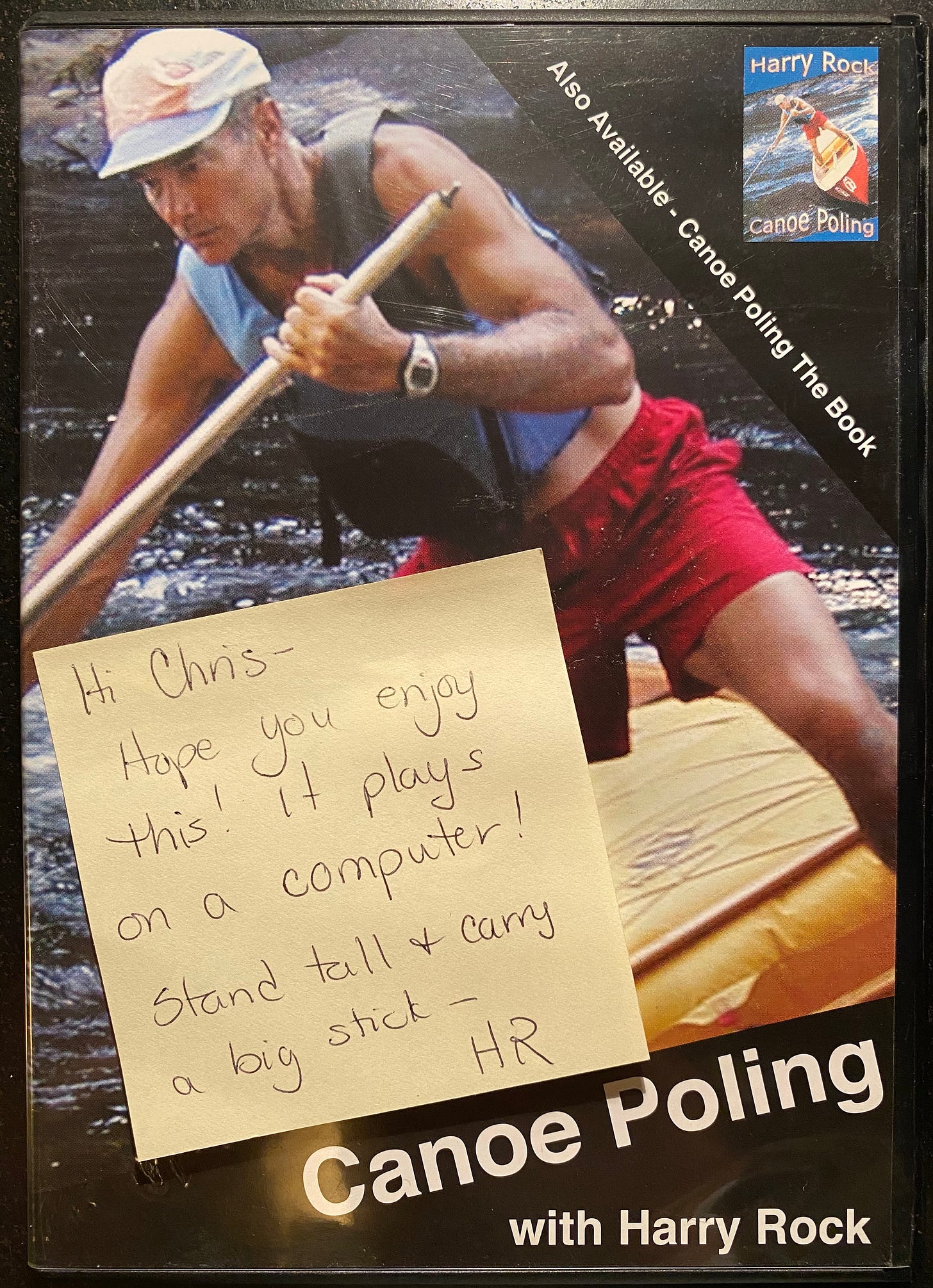

I made my first canoe pole from a busted young hackberry trunk. It was okay, but bent. Then I tried a twelve-foot wooden dowel from Home Depot, which worked great once you nailed some metal shoes on it, but was pretty heavy. So I did some research, and found an entire subculture of canoe poling nerds, and a few guys who make and sell poles from lighter and more durable materials. And I bought one, which included a bonus DVD on how to use it, personalized with one of the most simultaneously awesome and weird motivational messages I have ever received in the mail.

The DVD is basically some Wes Anderson-worthy vintage video of our guide teaching a bunch of summer vacationers the surprising capabilities the pole endows any canoeist. Most of the things he teaches are things you can’t really learn on a video, like how to use the pole and balance the canoe to move upstream through rapids. A few are revelatory, like the fact that if you windmill a canoe pole like the world’s craziest kayak paddle it works to propel you at high speed through calm waters, even though there are no blades. And there are nuggets of existential empowerment, like the part where Harry tells his students he is endowing them with “the ability to do what we’re not supposed to do…go where we’re not supposed to go.”

I was thinking about the obscure art of canoe poling this week because I had the strange experience of watching myself doing exactly that, on a beautifully produced documentary television program that launched Friday. It’s such a crazy-looking thing the first time you see it, especially when what you are seeing is some cinematographer’s vision of you, from a drone, one little human going where he’s not supposed to go, surrounded by epic landscape and a rising sun.

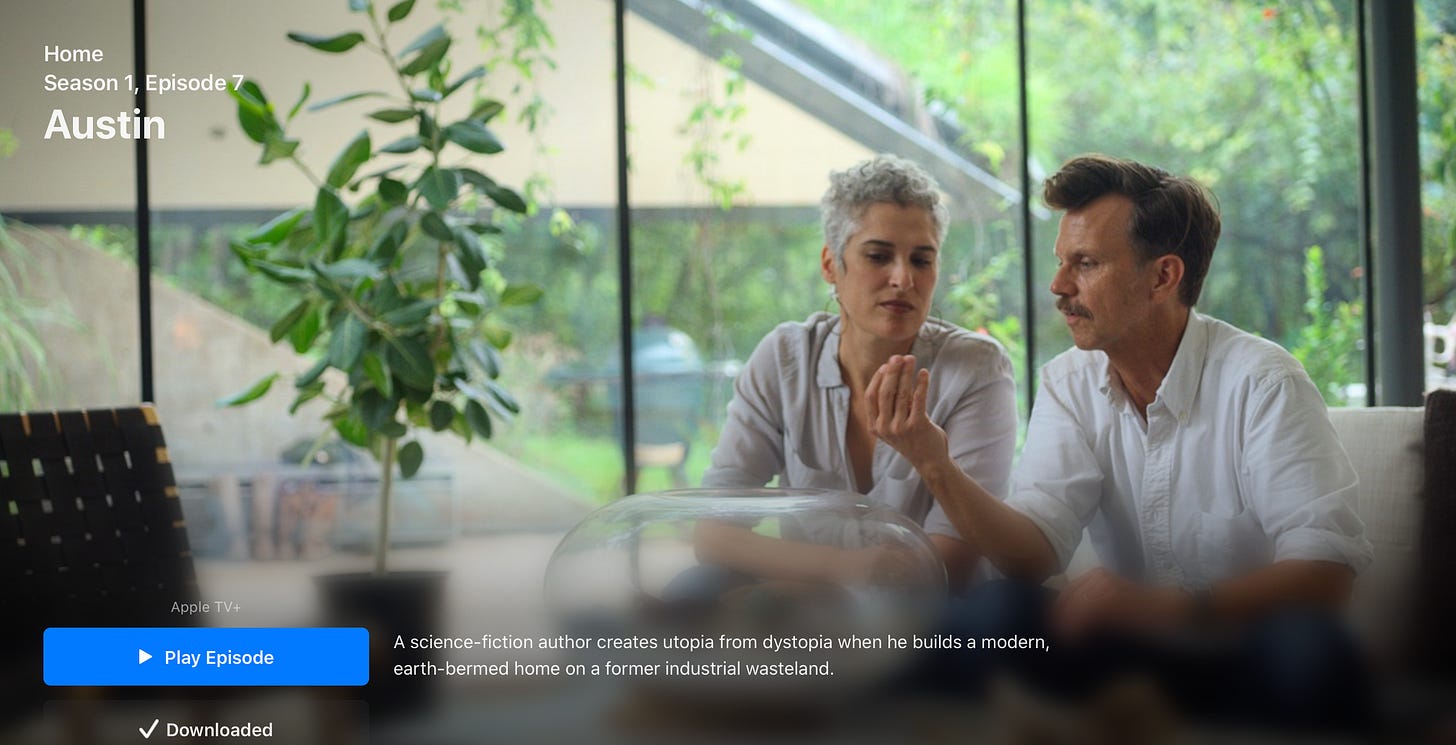

When we were first approached about the opportunity to participate in the Apple TV + series HOME, my wife and I were wary. We are pretty private people, at least with respect to our domestic life, and the idea of inviting the whole world into your home is a lot to get your head around. But in the end, we concluded it was too good an opportunity to share the ideas we believe in, about rewilding the city and hacking the way we think about the domus. And we were very lucky to get to work with an incredible team helmed by director Doug Pray, who understand the story we and our neighbors had to share about how our project fits into a wider movement and deeper history, and who had the gifts to draw out how our intersections with urban nature had impacted us in our personal lives.

The end result is beautifully done, and accurately captures the story of how we took on this project. In a short 30 minutes, it manages to tell some of the dark history of this land, and provide a window into the possibility of a more ecotopian future. We can’t invite our friends over during the pandemic, but this strange moment makes it feel like inviting the whole world over instead is the perfect thing to do. We are honored to have had the opportunity to be part of this, and hopeful that the story and message will inspire others to take on similar projects. The whole series is remarkable, with a diverse array of equally utopian projects, and perfect viewing on the eve of Earth Day.

In addition to epic canoe poling shots, it has what I am confident is the most extreme weeding footage ever committed to film.

To make it, we had to help the filmmakers go where they are not supposed to go. They gamely tagged along with me bushwhacking the river and woods, captured some Tarkovsky-worthy vignettes of the ruins of the twentieth century being overtaken by wild green, and adventured out with my wife and me for an evening encounter with a gigantic colony of bats. They got more great stuff than could make the final cut, but succeeded in telling what I think is a wonderfully inclusive and affirming story of urban ecology, community action, and the possibility of green futures—a remarkable achievement for what is at its essence a home & garden show.

I always have mixed feelings about bringing eyeballs on this weird little zone where we live. This is a place that exists because it is invisible to most people. Attention to a place, especially through the enhanced romantic lens of gifted cinematographers and storytellers, draws people, and people displace the wild. Even us—I think about it every time I walk through the woods, how my very presence is a disturbance of the habitat, of marginalized urban animals who are a lot more wary of us. But if we can help people see their own similar connections and complex relationships with the wild nature around them, I like to think, we might even be able to find our way to a future we would all want to live in.

You can’t build a connection with nature by watching a TV show. But maybe a TV show can be a trailhead for more self-directed paths of personal exploration, by helping people to find their own way outside, and into unexpected encounters with the wildness that exists all around us but we rarely see through our screens. To remember that our real home is the land on which we live.

Here’s the trailer, if you’re curious:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="

frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

And here’s the link to the episode featuring our project—HOME, Episode 7, Austin.

And in case the coral snake video in the show isn’t enough for you, here’s an even bigger one two years ago yesterday, slithering around my snake boots, something I prefer they do when I am wearing said boots.

Have a safe week.

Also, the show is so charming and inspiring!

Another great post! Have you ever watched the Bill Mason canoeing videos? They are some of my favorites, I think you'd enjoy them. I believe this episode has him poling https://www.nfb.ca/film/path_of_the_paddle_solo_whitewater/