Hallmark cards from dystopia

Tuesday afternoon I stepped out to stretch my legs after a long telephone conversation and heard the call of an osprey nearby. The osprey’s cry in the sky has qualities of whistle, squeal, and scream, usually expressed in a slow-motion staccato at an altitude that carries far. This one sounded different, and when I spotted the bird there circling over our house, backlit by the blazing afternoon sun in the way they say the Red Baron used to attack, I could see it had something in its talons. Not the silver flash of fish scale one normally sees in the clutches of an osprey, but something dark and furry. The river hawk would glide a little bit, then flap and clutch tighter at the same time as it squealed, in a way that made you think it wasn’t the bird making the noise, but the small mammal it was carrying home for a late lunch. And then the squeals stopped.

I’d had unlikely bird narratives in my head all week, after seeing seagulls scavenging food in the parking lot of a West Des Moines Walmart the Wednesday morning before Thanksgiving.

Turns out seagulls near cornfields are perfectly common—like the osprey, they have found freshwater habitat deep in the continent as or more hospitable as the coastal habitats where they likely originated, and seem to adapt well to human alteration of those landscapes. These gulls were near a major creek down the hill from where I grew up that is part of the Mississippi River watershed, and on the bus route I used to take to work on cold winter days in the 90s. I have a fond memory of the Black Friday when I went into the office to crank on an IPO and, when the bus stopped at that very same Walmart on my reverse commute home, a pair of the wackier regulars on that route boarded with plastic bags full of gifts and managed to get the rest of us to join them in singing seasonal songs. Hallmark cards from dystopia, coming your way.

When we got to grandma and grandpa’s, we spent long hours at the kitchen table as our free-range toddler rampaged through their rambling house, and I spent a healthy chunk of that time reading the bird books my folks keep there by the window out onto their pond, next to the binoculars. I read Pete Dunne’s Hawks in Flight, but wanted to find the more interesting-sounding book mentioned in his jacket bio, Tales of a Low Rent Birder. The most compelling of the guide books was an old one, Waterfowl in Iowa (1947), which despite (or maybe because of) its hyper-local emphasis proved the most surprisingly profound, providing a window into the ecological bounty that once existed in the American heartland, before it was replaced by plowed fields slowly evolving into sterile subdivisions.

The book was written right after World War Two by the director of the state history museum, Jack W. Musgrove, and his partner Mary R. Musgrove, and illustrated by museum staff artist Maynard Reece, who went on to become a well-known wildlife painter after he won his first duck stamp commission right around the time Waterfowl in Iowa came out. Reece lived down the street from us when I was a kid, and I caught a glimpse of his studio once, in a contemporary house tucked back in the woods, and tried to imagine a life painting pictures of ducks all day. Maybe I should have asked him if he was looking for apprentices.

Reece’s pen and ink drawings are integrated with the text in a way that lends it remarkable grace for a funny little guidebook, but the Musgroves’ writing is what makes it a deeper read. Field guide as Anthropocene natural history, without thinking of itself that way. It opens with a description of the abundant species of waterfowl that once enjoyed the land between the Mississippi and the Missouri as its nesting grounds, but notes that by the time of the war, right around a century after settlement and statehood, most of the marshland that once provided breeding habitat for ducks, geese and swans had been tiled and “disappeared under the corn planter.” But the ducks still passed through on their way to breeding grounds further north, stopping to feed and “grow fat on waste grain.”

Growing up in the Corn Belt a few decades after the writing of that book, I never saw many waterfowl. Maybe I wasn’t paying attention or going to the right spots, but what I remember is the paradox that all that vast green countryside was so completely devoid of wild nature. The rolling prairies and riverine woodlands that had covered that expanse had been almost entirely subjugated to the industrial production of grain, a rape of the land wrapped up in the bucolic myth of the family farm. If you saw pheasants, it was almost always in the liminal spaces—along the fencerows and rights of way.

Smallville really is populated by aliens. Or so I thought reading another regional book I found in my folks’ library, J.B. Newhall’s A Glimpse of Iowa in 1846, a text that reminds you that all real estate brochures are also histories of violence.

“Soon after the termination of the Indian War of 1832 (generally known as the Black Hawk War) many of those hardy and enterprising pioneers, ever to be found in a frontier country, began to perambulate the western shore of the Mississippi in search of choice ‘claims,’ eligible Town Sites, Mill Seats, &c.; and, for a season, it was quite difficult for the small garrison of U.S. troops, then stationed at Rock Island, to keep the white men from trespassing upon their Indian neighbors. The time at length arrived, agreeable to treaty stipulations, for the Indians to leave their ancient hunting grounds.”

As we followed our own path to the piece of that land where my parents retired, we saw a bald eagle over the old highway, fighting with a murder of crows over some fresh roadkill. Then we turned onto the gravel road, saw some wild turkey in the bush by an abandoned house, passed a new concentration camp for chickens, and saw that the old red barn where they used to breed ponies for sale by mail order through the Sears Catalog has finally collapsed into a pile of lumber.

The natural history of American colonization is easy to see in the way the state has partitioned the land, as you drive to your destination on that grid of roads devoted to getting the grain to market, a grid that also marks the subdivision of the land into parcels allocated to those granted the right by the state to share in the profits it can produce in exchange for their labor. Many of the first settlers in Central Iowa got their parcels as rewards for service in the war with Mexico that conquered most of the land between Texas and the Pacific, but their twentieth century heirs secured their tenure with mortgages. A perpetuation of feudalism through a financial system that lets it look like freedom.

In the 80s, that system went through a crisis, bad enough that the newspapers filled with stories of farmers heading into town and shooting their bankers. Much of the land that had been owned by those family farmers went out of production, and started to go back to wild. Prairie restoration became a thing, as people like my parents starting burning the land to heal it.

When you go for a solitary trail run through those black fields so freshly burned you can still smell the smoke, you can’t help but be struck by how apocalyptic it is, even if you have witnessed the natural bounty it yields in spring. Restoration is a misleading term for that kind of undertaking, encoding as it does the fantasy that you can bring back what was there before. Rewilding is more like it, even if it’s a kind of wildness that is cultivated by human mastery of fire and control over the reproduction of other species. And the story is always more complicated, like when you learn many of the Indians used fire to manipulate the landscape in service of their own appetites, or when you learn that the pheasants you thought of as the leading symbols of endangered Midwestern wildness are actually an invasive species.

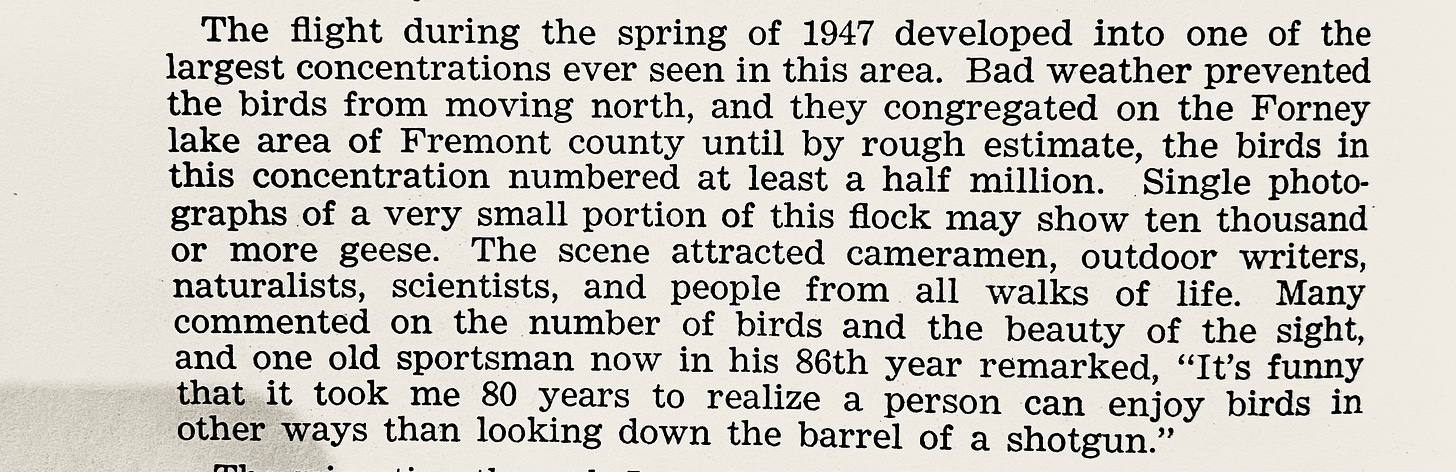

There’s a passage in Waterfowl of Iowa that gives a glimpse of the possibility of bringing back the experience of wild birds so abundant they darken the sky. It’s a recount of what happened one season when the book was being written, in the fertile floodplains of the Missouri River:

When I looked up the spot described in this passage, I saw it was near the town where my dad grew up. And since he was sitting right there, I asked him, and he said he remembered hearing the birds that year, a cacophony that would wake him up at night. It reminded me how recent the banishing of the American wild really is, and how quickly one could expect some of these species to return to the spaces where we make an effort to share our habitat. But then I read the news, and got to wondering whether our culture has finally discovered the possibility of rewilding too late, as the climate migrants start pushing through the border fortifications. Maybe the real rewilding will follow the crisis to come, on a less crowded planet.

While we were away, I had the trailcam up at the back gate, curious to see what critters were out and about in the woods behind the factories as winter sets in. On the reel I found a whole lot of big fat raccoons, far more than I’ve ever seen around here, a bunch of plump armadillos digging around in the dirt, a few opossums, two lost fishermen, and just one loping midnight coyote. But there were more wild canids out there. Tuesday night I heard the first Joker laughs of the season down in the dark woods. That sound is crazy creepy, but also reassuring in its reminder that truly wild predators can still survive in the edges of the city.

The next day I encountered a more novel creature in the process of its domestication—a robot being trained by one of its human handlers to navigate the corner of Sixth & Congress in the heart of downtown Austin. It was a food delivery bot, an innovation whose market opportunity the venture capitalists no doubt see as especially promising post-quarantine. It’s crazy how unremarkable this sort of science fictional 21st century scene now is, to find a young robot and its trainer out practicing on the downtown sidewalks, preparing to liberate another category of workers from their drudgery and/or displace them from their work. That the trainer had to lift his bot’s back tire at every turn suggested the machines are not yet as smart as their developers want us to believe. That he had to wear a helmet made me wonder whether that electric mule ever throws its rider.

It was only when I looked at the photo later that I was reminded how the spot the robot and handler were hogging was where Leslie Cochran, the poster boy of Keeping Austin Weird, used to spend most of his time. You knew the aspiration embodied in that slogan was doomed as soon as they started selling it at the airport, but Wednesday’s vignette—on the same day that I read Tesla has bought more land downriver, across the Colorado from its factory site, and SpaceX has jobs posted for a new manufacturing facility nearby—confirmed how completely the Chamber of Commerce version of Austin has turned the birthplace of cyberpunk into a cute little corner of the Sprawl. At least it’s one where the bots can bring you breakfast tacos.

The roundup

Elsewhere in cyberspace, this week’s Wall Street Journal brought the news about real-world investment funds investing millions of dollars in real estate in virtual worlds. And the NYT ran an excellent story by Edgar Sandoval about the gentrification and displacement in Austin, with a focus on Montopolis, the neighborhood across the river from where we live, and interviews with people we know or have worked with.

In my parents’ library I also found several volumes of The Best American Essays and The Best American Short Stories from most of the years 1985 through 1993, selections of which I worked my way through during our visit. The tables of contents in those books remind you what a different editorial world that was, but the editors of Fiction did a better job at showcasing diverse voices than Essays—even Raymond Carver, whose introduction about how he picked the short stores of 1986 had a much more glib voice than his minimalist fiction. The best gem I found for readers of this newsletter was Barry Lopez’s essay “The Stone Horse,” originally published in Antaeus, about a journey Lopez took to find an ancient intaglio made from rocks in a Mojave arroyo. I found an online version here, and it’s a great riff on what encounters with antiquities in the American landscape feel like and make you think about, as well as a wonderful story of how one went about finding a special spot in the middle of nowhere in a world before digital maps and smartphones.

And on the subject of rewilding, this week the smartphone bot reminded me of the time six years ago when I found a snake crawling out of our bathroom wall as I was using it:

Not exactly what we had in mind when we set out to make our home one that celebrates biodiversity in its very bones, but still a sign of success.

Saturday, December 11, I’ll be participating in a group reading to help launch the Carceral Edgelands project of the Bureau of Experimental Ethnography, which aims to use landscape-focused writing to explore the aesthetics and politics of immigrant detention sites. More to come on that next week.

My parents also broke out the photo albums while we visited, including one album of snapshots curated by my maternal grandmother that made me realize they immigrated here carrying memories of a world that really did look like a Caspar David Friedrich painting. Here’s one from the Rhon Mountains in Weimar Germany, probably early 1920s.

More from this album at my Twitter feed.

Have a safe week. Schedule permitting, next Sunday I’ll have a report from a walk around the exurban climate refugee detention center. In the meantime, here’s a video that shows what you might see if you look when you hear the osprey’s cry, even in the flightpath of the airport.

It's rare that I don't get to absorb Field Notes hot off the presses, but my Covid booster won out yesterday. Barely.

Great post. You’re such a wonderful writer. Thanks and keep them coming.

A collection of your observations would make a terrific book!