Flycatchers and fighter jets

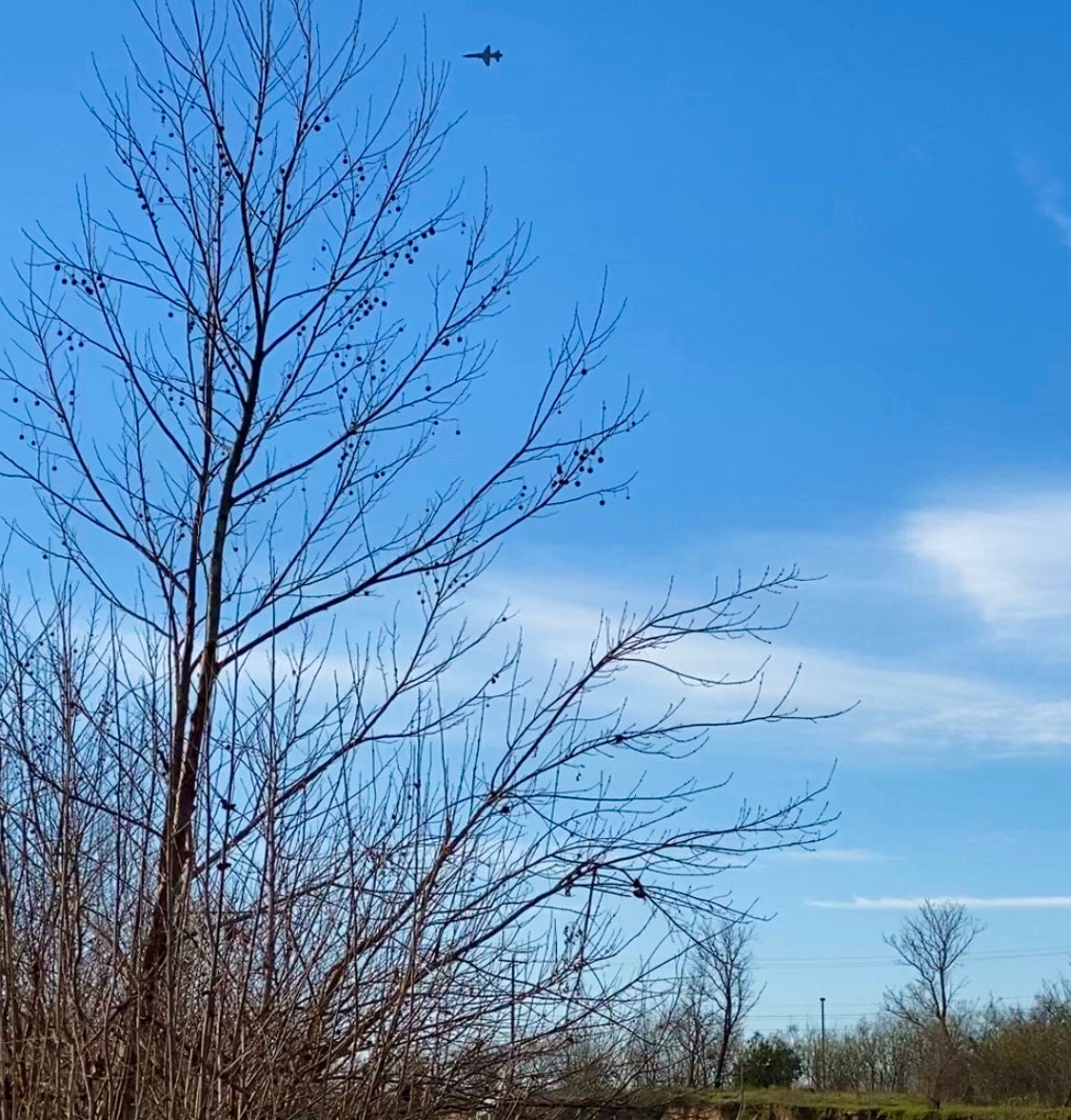

Thursday morning, not long after those jaw-dropping unemployment numbers came over the wires, we saw the first scissor-tailed flycatchers of the season. Just a pair of them flying over the onramps, backlit by an overcast sky, but with the unmistakeable silhouette of the Texas quetzal. They were headed in the direction of the airport, but maybe they weren’t going that far.

The first time I saw one of those birds was right around the last time the American economy cratered, more than a decade ago, picking my son up from school. We were pulling out when I saw it alight in a sad little developer tree, with those insane tailfeathers twice as long as the body. Hugo knew what they were, and told me the name.

I see them more often now, in the warm months. They seem to like it around this part of town. Once in a while I see them down by the river, often in the brushy area where the riparian plants grow tall in the gravel and the birds find mayflies and other bugs that congregate near the water. More often I see them in the flat fields and isolated trees around the dairy plant, where the refrigerated trucks idle all night long next to the nature preserve.

A couple of years ago I found a group of flycatchers dancing in the thermals coming off the frontage road on an early summer afternoon, zipping between the power lines and a big live oak behind the animal shelter. It was the first time I had ever really seen how functional those tailfeathers are, the way they use them to make these abrupt sharp turns, banking hard like little fighter jets, grabbing the agile flying insects from the air. And it is only when they are in that turboboosted mode that they reveal their full colors, and that apricot underwing explodes into orange.

Around the same time as I saw those first flycatchers, Hugo and I hiked into the alien landscape of White Sands at daybreak, and found ourselves buzzed by a pair of low-flying Luftwaffe trainers out of Alamogordo, painted bright orange, like apparitions out of some Gerry Anderson fever dream. You can always hear the fighter jets before you see them, which is pretty often here on the river near the airport, and by the time you look they are usually banking away. That is also true of flycatchers, sometimes, but the flycatchers are a lot quieter.

My friend Rudy Rucker remarked after reading last week’s Field Notes that he was loving the newsletter but having trouble visualizing where in the hell it is I am reporting from. Rudy, one of the world’s most mind-blowing science fiction writers as well as a mathematician and computer scientist, lives in Northern California, and his blog was an early inspiration for me in thinking about the connections between sf and nature writing. He used to often post these trippy little videos of coastal creeks and currents, accompanied by improvised odes to the gnarl. So this week I thought would answer his question with a clearer description of this place. Maybe more of a guide to how one finds places like this than a map to this particular one.

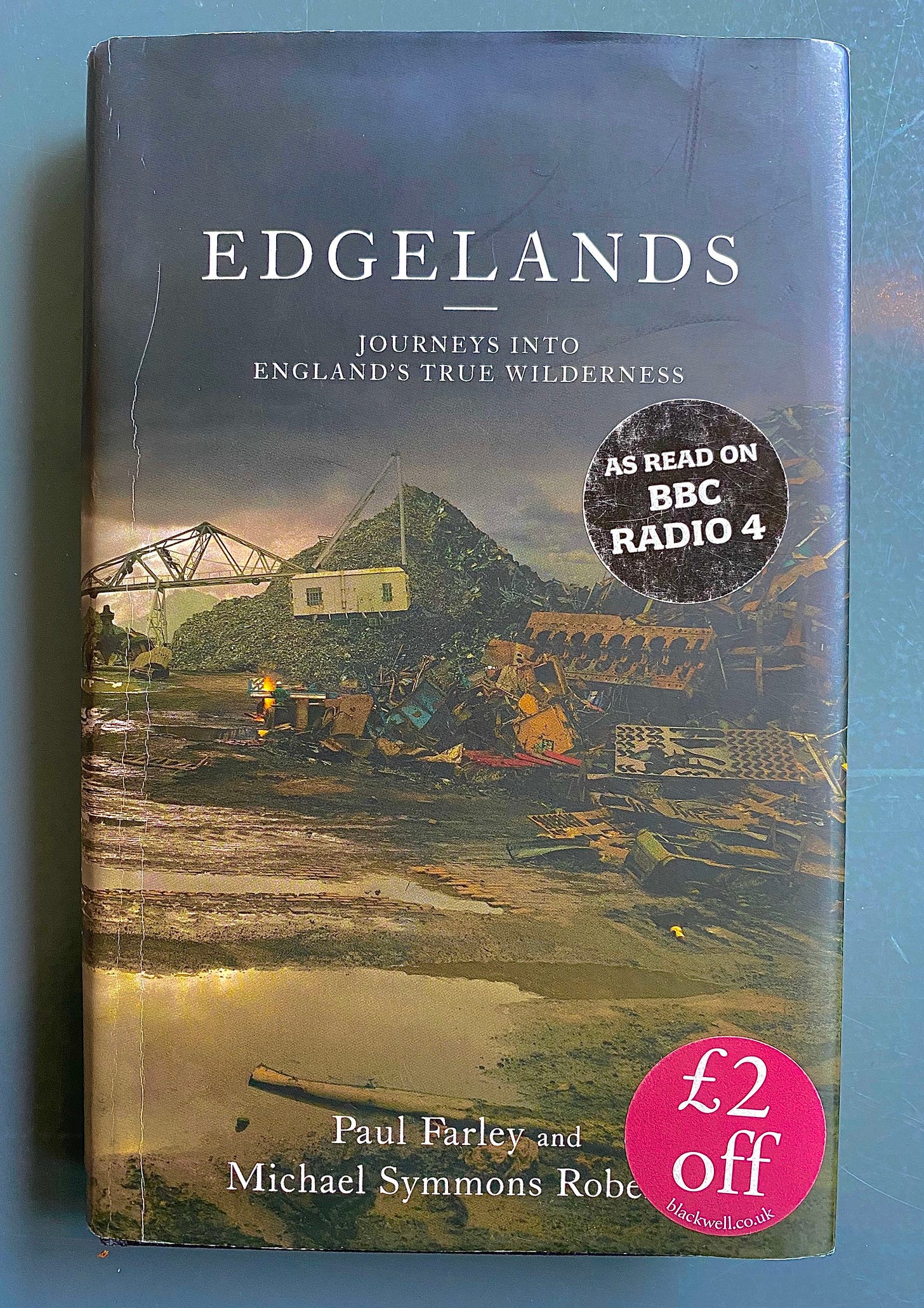

The English have an entire literature about places like this, and a name that perfectly describes them: edgelands. I had already spent a lifetime exploring these kinds of spaces before I learned that term, reading the Saturday Guardian on a train from London to Oxford on another trip with my son back in 2011. The review was of Edgelands, by two poets, Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, who had the genius idea to document their lifelong experiences of those zones at the edges of old cities where human development runs into wild nature.

The term they appropriated as their title was originally coined by the ecologist Marion Shoard. It’s the kind of word that by its very existence gives you the means to talk about a certain kind of place you have always known but could never name. A word loaded with just the right combination of descriptive accuracy and lyrical romance. Shoard opens the essay with a pretty great universal description:

Between urban and rural stands a kind of landscape quite different from either. Often vast in area, though hardly noticed, it is characterised by rubbish tips and warehouses, superstores and derelict industrial plant, office parks and gypsy encampments, golf courses, allotments and fragmented, frequently scruffy, farmland. All these heterogenous elements are arranged in an unruly and often apparently chaotic fashion against a background of unkempt wasteland frequently swathed in riotous growths of colourful plants, both native and exotic. This peculiar landscape is only the latest version of an interfacial rim that has always separated settlements from the countryside. In our own age, however, this zone has expanded vastly in area, complexity and singularity. Huge numbers of people now spend much of their time living, working or moving within or through it. Yet for most of us, most of the time, this mysterious no man's land passes unnoticed: in our imaginations, as opposed to our actual lives, it barely exists. When we deliberately visit it, this is often for mundane activities like taking the car to be serviced or household waste to the disposal plant, which we choose to discount as part of our lives. If we actually live or work there, we usually wish we did not.

For whatever reason, I have always sought places like this out, since I was a kid. Partly because these places are where you can experience wild nature inside the city. But also for the same reasons I am drawn to fantastic literature—places like these are where everyday wonder and the surreal naturally occur. And to find it, you basically just have to walk into space where people rarely go.

I have used the term “edgelands” heavily since then, even as I have grown wary of it. Partly because I think it doesn’t apply as perfectly outside of uniquely English places where aged industrial facilities loom over the Shire. And because I think places like this don’t even want to have a name, because naming them takes away some of their power and mystery. It’s the same reason I am reflexively wary (in addition to being insecurely envious) of those people who can walk in the woods and proudly display their knowledge of the names of all the things they see. Taxonomy is the enemy of wonder.

(The academic ecologists have a clumsy acronym for such places: the WUI, for wildlife-urban interface. Before I learned the term edgelands, I thought of these places as urban negative space.)

The area where we live is very American, more specifically very Texan, even though I have encountered zones just like this in Seoul, Barcelona, Tijuana, and Munich. It’s an area of urban wilderness that has been allowed to flourish pretty much by accident. Like many cities, Austin occupies land along a river. To generate energy and control the floods, in the 1960s the town erected a dam that turned the river into a lake where it flows through downtown and the affluent old residential neighborhoods. The dam was built at a natural low-water crossing at the eastern edge of town, path of an ancient trail, and below the dam the river flows in more or less its natural channel, all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.

Around the same time, the town zoned the area along the north bank below the dam for industrial land uses, many of which are still in operation, others of which have slowly phased out as their business moved on when the Air Force base across the river was closed and redeveloped as an airport. The Quonset hut machine shops are turning into micro-breweries.

They are building condos now on the empty lot where the petroleum tank farm used to be. A network of transmission conduits ran from there to the Air Force base and other users. One segment of buried pipeline bisected this lot I bought at the nadir of the financial crisis, around the time I saw that first flycatcher.

Our house is a little eco-bunker we built into the trench where the pipeline used to be, on a side street that is a remnant of the old route to the ferry landing. It’s a street with houses on one side and small industrial operations on the other. Our immediate neighbors include a door factory and the place where they make wind chimes.

The big industrial facilities around here are barricaded with high security to keep human thieves and saboteurs out. As a consequence, they have also mostly kept humans out of the woods behind them, allowing a thick pocket of interstitial wilderness to grow up along the river. Down there is a zone of owls and raptors, coyotes and wild dogs, cactus and cottonwoods, and diverse waterfowl. The thick mustang vine that hangs from the hackberrys lends the woods a gothic quality. So does the trash.

If your cleared it with a bulldozer, it probably wouldn’t seem particularly big. But the woods are thick, and there are no real trails, and so they seem almost endless when you are down there in them. I usually go out at daybreak, which is the best time to see wildlife. Rarely do you encounter other people at that hour, and the ones you do see are usually other weirdos. I used to see this dude who carried a big wooden staff walking his pack of six German shepherds, even in the driving rain. There’s a guy who lives in an abandoned building by the highway, not far from that flycatcher tree, who I see pretty often and have gotten to know pretty well. Often I see fishermen on the river, and once I came upon a pair of duck hunters walking in the shallows, shotguns and all. I also find the things the people who go there at night leave behind.

Two Christmases ago I was walking along the river and a voice called out from the opposite side. I looked and saw a guy working his way along the eroded bank, looking for fossils. We talked for a while about stegosaurus plates and broken pottery. Before I moved on, he told me, for the second time: “Look into fossil feces. It will change your game.”

There are plenty of fossils in the river, maybe not where he was looking. Cretaceous shells, mostly, often bigger than your fist. The river delivers all sorts of messages from across time. Fragments of old settler pottery, rusting hunks of metal from past industrial uses, abandoned cars and refrigerators, and tools of the people who lived here before. One of my neighbors found an item that the archaeologists at the university identified as a 10,000-year-old toolmaking gouge. The river also fills the woods with flotsam from boats and backyards, and every walk turns into an Anthropocene Easter egg hunt.

It was still raining when I took the dogs out yesterday after the lightning stopped just before sunup. I saw some uncommon bird on the opposite side of the river, as often happens when there’s a storm, not even close enough to identify—looked like it might even have been a bald eagle but that would be a first. The river was flooded, so we cut back in through the woods. We meandered into a thick patch of tasajillo, but found a path through, past a pretty elaborate camp covered in big tarps and complete with a hammock. Until we came up behind the dairy plant, and followed the old right of way from the ferry landing back toward the house.

The dairy plant was busy as always, but the nearby construction sites and all the small factories and warehouses that supply them were quiet for the first time all week. The builders flipped when the shelter in place order mandated most of them suspend operations, and made such a ruckus that their friends in City Hall caved and gave them one. It was a reminder of what really matters here in the fastest growing city in America, and how much of the prosperity Texas enjoys is derived from the labor of people who may not even have the legal status to be able to equitably bargain for their safety on the job.

Sometimes the sound of those construction sites, just as much as the sound of the low-flying fighter jets, reminds me that even though the Air Force base is gone, this is still colonized space. These woods are a pocket of uncolonized or decolonized space in the margins of that dominion. And no matter how much you might fancy yourself its advocate and conservationist, you have to acknowledge that you are one of the colonizers. The animals let you know, when they return your gaze. Understanding that is a helpful thing, even when commerce has been suspended to such an extent that you can almost imagine the whole city working its way back to wild.

Last week I was riffing about Caspar David Friedrich’s “Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog.” This week, while looking for photos that would help situate this neighborhood, I was reminded of the house a few blocks away that has that painting on the garage door.

Have a safe week, and try to get lost if you have time.

Keep them coming.