Flight trackers and fungus garden futures

No. 172

Thursday morning, as the so-called Wolf Moon had begun to wane just a little, I saw Mars there in the western sky next to Castor and Pollux, the stars of my astrological sign that I could never figure out how to find when I was a boy. Just below them was a fourth pinpoint of light, this one machine blinking, moving slowly across the sky from north to south.

I looked it up on my phone, and saw it was Turkish Airlines Flight 181—a direct flight from Istanbul to Mexico City, flying 493 mph at an altitude of 37,975 feet above the western edge of metropolitan Austin. It felt like a sure sign that we are 25 years into the 21st century, and that all roads no longer lead to Rome. I wondered who the passengers are that fill the 787 Dreamliner, what commerce warrants making the run every other day, how much is business and how much tourism. The flight tracker app noted the itinerary includes a stop in Cancun before heading back to Istanbul, and I imagined the crew enjoying their rest day on the playa before the return flight, a set up ripe for a sun-drenched neo-noir, post-America style.

A couple of hours earlier that morning, Blue Origin successfully launched the SpaceX competitor’s first rocket big enough to put heavy payloads into space. The plan is to put a new model cargo lander on the surface of the Moon later this year. Who or what will be in the lander, they don’t say.

It’s strange feeling, to have arrived so definitively in the future the twentieth century imagined, complete with private spaceports, robots on call, and lightspeed global communications networks, and simultaneously witness how extreme the cultural and political regression is in response. Networks open, but borders closed, as the inheritors of liberty earned for us by our king-killing revolutionary forbears blow their franchise on another season of warlord cosplay. Saturday’s Wall Street Journal has an astonishingly uncritical think piece about the arrival of a “New Age of Empire” in which Russia, China and the U.S. remake the world map through aggressive dominance. A week earlier the FT led the coverage of the sobering news that, in the year just ended, the world breached 1.5C of warming for the first time. In my speculative fiction, I’ve imagined near-future investment bankers who specialize in buying and selling national territory as climate change alters the map, and now they’re here for real.

If the news gets you wondering who owns the Moon, the legal answer is nobody, according to the Outer Space Treaty of 1967. But the reality is more like the law of nature: whoever can take it and hold it. And in 2015, under the Obama administration, US law was amended to provide that, while extraterrestrial planetary bodies remain the cosmic commons (for now), private property rights will be recognized in minerals extracted from asteroids and space resources.

Last year I read The Saga of the Greenlanders and Eirik the Red’s Saga, not knowing they were previews of coming attractions, complete with the son taking on his father’s dreams of empire building and colonizing. And as I think about my 5-year-old daughter’s future in a moment when something like that Viking ethos seems anachronistically ascendant, I keep gravitating to the story embedded within the sagas of Aud the Deep-Minded, the matriarch who, after the slaughter of her husband and then her son, built her own ark of escape in a Scottish forest, freed the thralls, launched their boat into cold seas and took her motley tribe to found their own new colony on a deserted Icelandic coast.

As her Disney princess phase seems to finally be waning like the passing of a long season, our daughter, the girl I used to carry into the pandemic-era woods on my back, has a fresh interest in what’s outdoors. We got a lot of time for that over her winter break, sometimes on foot, down in the secret valley of the urban river, where the transition from cold clear nights into bright sunny days brings a fog that obfuscates time, and sometimes on the bike Santa brought, cruising with fresh freedom past the graffiti-covered walls of our neighborhood’s abandoned factories while I run alongside. I’ve seen her mom lately trying out different ways to start obliquely teaching her only daughter about how this world works, and what’s coming, to get her ready for the future. It’s not easy.

On one of our bike rides last week we noticed a mound of leaf cutter ants that has established itself in the strip of dirt at the base of the tollway offramp, behind the looming wall of the parking garage that just went up on what had been, until this time last year, an edgeland grove of tall pecans that had somehow held out on an otherwise deserted traffic island. I pointed the mound out to Octavia, and explained what it was, and what the ants were doing to serve their underground gardener queen.

The Texas leaf cutters seem to get most active at the beginning of winter, even before the deer, coyotes and foxes that live in the urban woods get frisky. When the weather finally cools at the end of our six-month summer, the ants suddenly appear along the sidewalks and trails, making their own myrmecological roadways across ours, dispatching busy convoys that cut fragments of the winter greens already growing in the land and haul them back to the colony. They seem even busier than the grain-hauling harvester ants, and the brightly-colored nature of their cargo calls more attention.

They do not, as you might reasonably assume, eat the leaves. They use them as compost: culture for the garden of fungus maintained by the queen in her subterranean chamber, which is their only known food. The reason they are most active at the beginning of winter is because they are relocating their fungal gardens to deeper caverns before the hard freezes of January and February. The first of which is blowing in as I write this.

While likely not meaning to do so, this profile of Atta texana by Texas A&M urban extension entomologist Mike Merchant properly tells the story in a way that reads like a condensed fantasy novel channeling Burroughs:

Mating flights of Texas leaf cutting ant reproductives take place on clear, moonless nights during April, May and June. Prior to her nuptial flight the virgin queen stores a small portion of the fungus garden in a small cavity inside her mouth. After mating the winged males die, while mated queens drop to the ground, lose their wings and attempt to establish small nests beneath the soil.

After digging a small gallery in the soil, the queen takes the fungus wad from her mouth and begins to culture it as food for her first eggs. Initially the fungus is nourished by fecal material. Approximately 90 percent of this first brood will be eaten by the queen. The first worker ants will be quite small because of their limited food intake; however these first workers bring back leaf fragments to enlarge the fungus garden, thus providing more food for later broods. As the colony grows, worker ant size increases and becomes more variable. In mature colonies worker ants vary in size from 1/16 to 1/2 inch-long, with the larger ants serving as soldiers for nest defense.

Individual colonies can exist for years. Where adequate food is available, colonies may expand to contain over 2 million ants.

A friend this week called to tell me he just started reading Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler’s 1993 novel about a mixed-race community holding out in an imagined 2020s Los Angeles undergoing social and economic collapse as climate change settles in and national politics veer into Christian nationalist fascism. My friend wanted me to know how unsettlingly scary and close to home he’s finding it. I told him I didn’t need a trigger warning, having read it in 2015 for the first time, after I had written my own dystopian novel. Stories like that, you learn while writing one, are made from the material of the observed world, and real history. And what makes Butler’s story so powerful is the honesty with which she confronts the things we must endure to find our way through, to adapt, to survive, to make some semblance of the future we want to live in, to make some measure of justice in the world we find.

As I think about our friends and neighbors worried about deportation raids, wondering if we will experience another period in which the feds dispatch armed and armored vehicle patrols into residential neighborhoods to start another campaign of ethnic cleansing under due process of law, and the federalization of the kinds of regressive abolitions of liberty we have been experiencing here in Texas over the past two decades, I get hope from these alternative shoots that nature and history point us to. Stories of underground queens and other weirdos who make their own alternative colonies hidden in plain sight.

With Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler seemed to me to be trying to write her way to utopia by putting a dark mirror up to the dystopia of the now. She planned five books in the Parable series, but only finished two before she died too young. The third, Parable of the Trickster, was evidently to be the story of how the Aud-like woman of Sower seeds a new model community in the stars, as her grandchildren make their home on another world. Maybe, as she played out that scenario, she saw how hard it is to plausibly imagine the powers that dominate and mostly damage this planet not doing the same out there.

With luck, we may help our daughter develop the skills to deal with what’s coming, and even thrive and help others. Her big brother is already well on his way. Even if he, coincidentally, chose this weekend to leave the country.

Further Reading

A Natural History of Empty Lots is now available in the UK and Ireland. It should be officially available in Australia later in the year, and we’ll have some other news to share about the book soon.

Thanks to the amazing crowd that came out Friday night for my conversation with Moctezuma Seth Gonzalez at Austin’s new Livra Books. I’ll have some more Austin events coming up—watch this space.

For more on Texas leaf cutter ants and their co-evolved relationship with the fungus they grow, here’s a video look at an active colony from Chicagoan in South Texas Joey “Chonkosaurus” Santore of Crime Pays But Botany Doesn’t:

This 2014 L.A. Review of Books piece by Gerry Canavan went to the archives to take a closer look at Octavia Butler’s unwritten Parables.

Parable of the Sower was originally published by Four Walls Eight Windows, perhaps the coolest of the independent publishers of edgy SF in the 90s. Here’s an archive of their site and full catalog as it was when they were sold in 2004. Co-founder John Oakes is still doing amazing work with Colin Robinson at OR Books.

I wrote about Parable of the Sower and the idea of dystopia as realism in this 2017 piece for LitHub.

For a weekend matinee that has both human dystopia and the alien weirdness of ant colonies, check out Saul Bass’ insane, trippy 1974 feature Phase IV. This trailer from the Vinegar Syndrome Blu-Ray release gives a pretty good flavor:

My favorite reporting from the L.A. fires may be the work our friend Meghan McCarron is filing for The New York Times. A writer on the food beat, Meghan had an amazing piece last week about food service workers who lost their homes, including in a trailer park along the PCH, providing a powerful glimpse into how people get by at the nexus of wealth inequality and climate change. Meghan also shared her own experiences of the fires on her excellent newsletter, Second Breakfast.

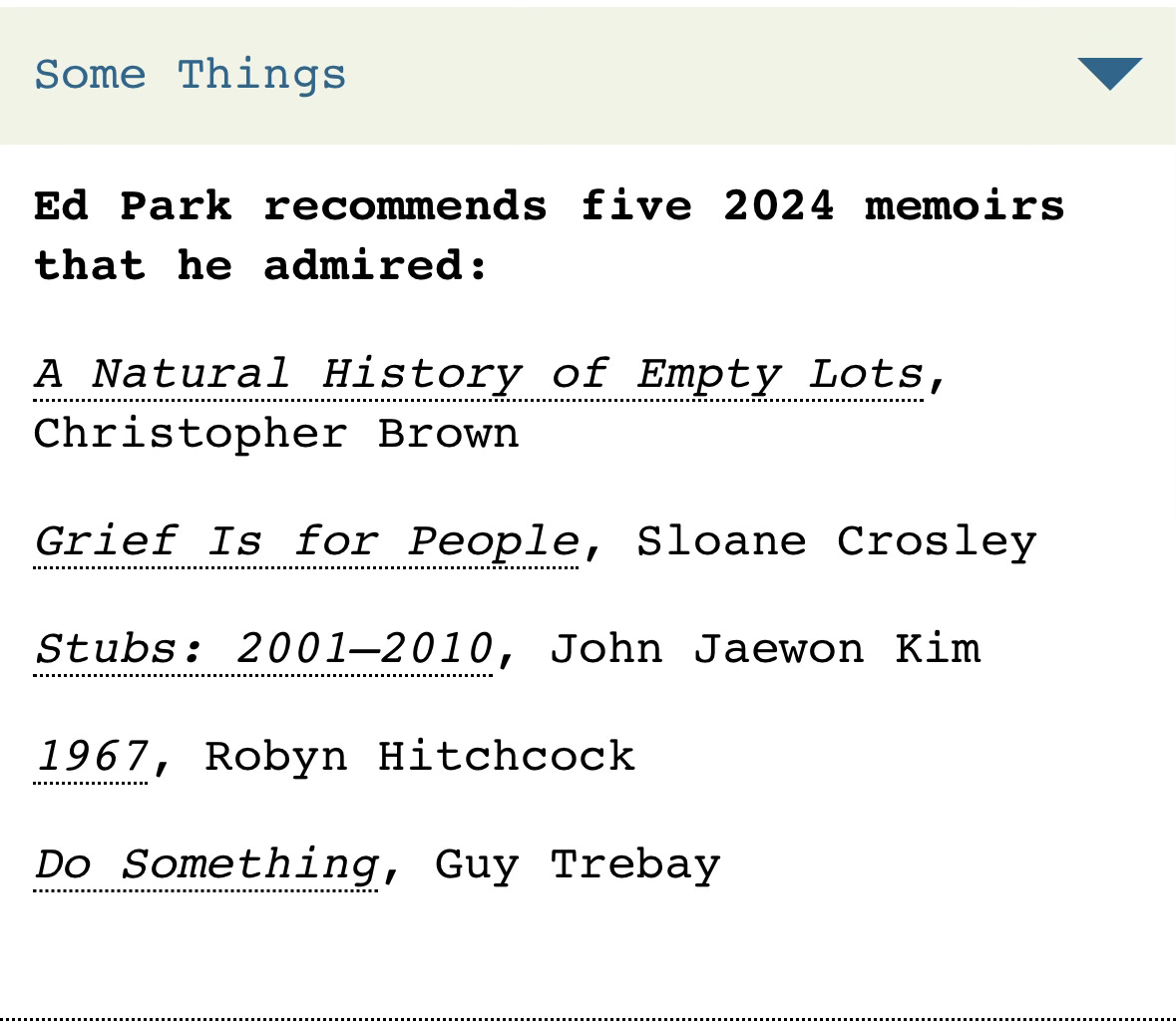

The Creative Independent has a wonderful interview up this week with Field Notes friend and 2024 Pulitzer finalist Ed Park. The interviewer Brandon Stosuy and Ed worked together early in their careers, which allows for an unusually honest and unguarded conversation. I especially loved Ed’s discussion about banging out his novel at outdoor tables in winter while his son was at hockey practice, an approach to getting shit done that may be easier for someone like Ed who grew up in Buffalo.

As a bonus, Ed includes Empty Lots at the end in a list of 5 memoirs he enjoyed in 2024:

I saw David Lynch’s Eraserhead not long after its initial release, at the Wakonda Theater in Des Moines, a strip mall two-screen cinema around the corner from my dad’s dental office that started showing weird stuff when I was in middle school. It implanted something in my teen brain that never left, as did Blue Velvet, which came out when I was in college in New Orleans. But maybe the best gift I ever got from David Lynch was his book on the creative process, Catching the Big Fish, which I picked up as a sale rack CD audio edition at Austin’s BookPeople—narrated by the author.

Catching the Big Fish is one of the only books on making art that’s ever really resonated me, somehow delivering distilled truth between lengthy asides about transcendental meditation. The core premise embedded in the title is that the best artistic visions are conjured by figuring out how to lure the “big fish” of the subconscious up from the fathoms behind your forehead and closer to the surface of your mind. For him, that was mainly through TM, but we each have our own ways to momentarily get to that state. There’s a nice long sample of him reading the book available here. Thinking about the gifts of David Lynch this week has been a nice antidote to the rest of the news, and I’m looking forward to rewatching his work as we come to terms with America 2025 and its strange mutations.

Lastly, the best thing I’ve read as we prepare for tomorrow’s inauguration is this T.J. Clark piece in the new issue of the LRB.

Stay safe and warm.

Great one, as always—have been thinking a lot about "the skills to deal with what’s coming" with my newborn. Have you seen First Reformed?

Maybe obliquely related, a new study shows that some ants remember the scent of their enemies.

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(24)01595-1?

This is packed with good stuff today. Plus leaf cutter ants.