Fahr'n Fahr'n Fahr'n

Field Notes from from a Memorial Day road trip, with time travel

The first service area on the Kansas Turnpike as you roll into the Wichita Vortex from the south is the one where they give out the free maps that tell you all the places you can visit. I have a hat I bought in the gift shop there a few years ago, a green ball cap embroidered with a picture of a buffalo and the name of the state. The buffalo images are everywhere when you cross the Great Plains, as mascots on the sides of municipal water towers and totems outside the run-down motels, but you never see any real ones.

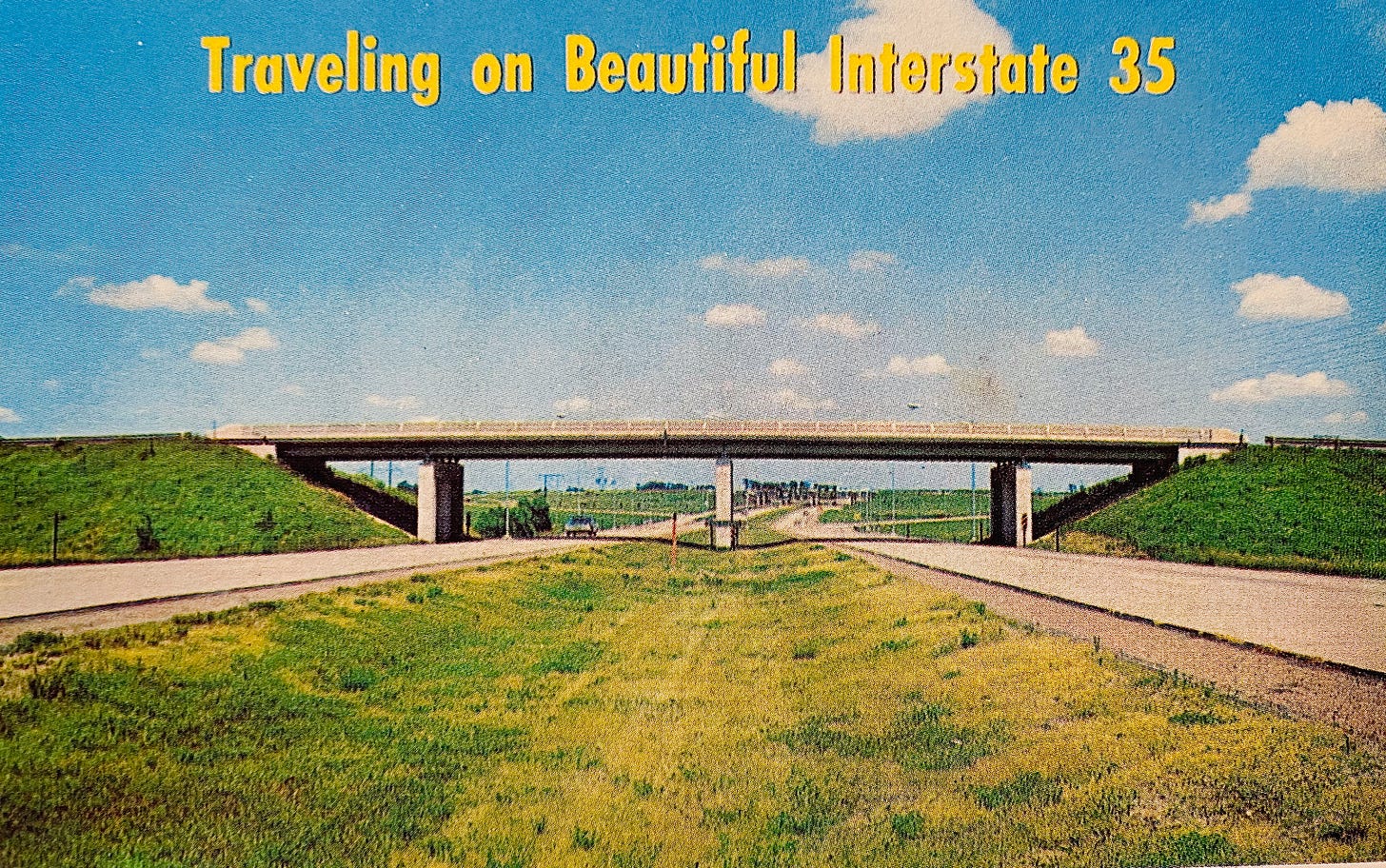

The interstate highway we drove up to Iowa and back this week follows a pathway that was made by big herds of those migratory megafauna. Sometimes you can sense their traces in the land, when you pass through a section that lets you see how they navigated the most efficient route through the landscape, and left the path for you to find your way after your ancestors exterminated theirs. A couple of years ago I made the detour to the Great Salt Plains in northern Oklahoma, an ancient inland oasis that has been made into a national wildlife refuge, and you could really feel it there, the way this whole continent was once an open range.

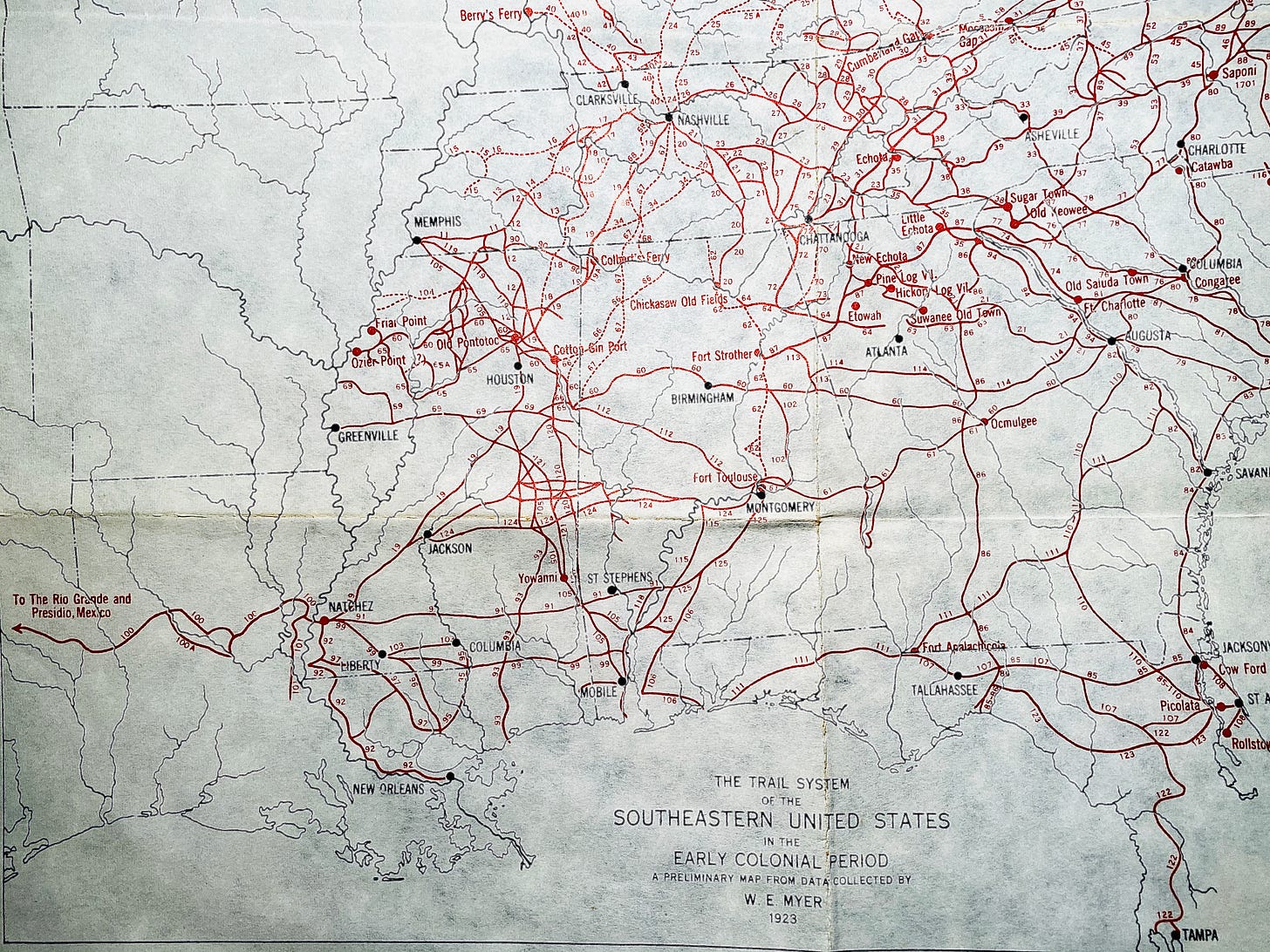

After the interstates were built, people wrote romantic histories of the earlier generations of American highways, like the Jefferson Highway I used for a rural route diaper run last week. Most of those books are Route 66-style nostalgia trips, but they often embed oblique elegies, suggesting the deeper histories of those roads as pioneer trails that began as Indian trails and animal trails before that. It was in one of those books that I first learned how far east the buffalo once roamed.

When I was working on Tropic of Kansas, I read Life in the Saddle by Frank Collinson, an Englishman who ran off to America after leaving boarding school in 1872. He became a cowboy, and then joined the great buffalo hunts that made room for the domestication of the West. Collinson tells how in the spring of 1877 he and two partners managed to slaughter enough buffalo among the three of them to sell eleven-thousand hides, six-thousand buffalo tongues, and forty-five thousand pounds of buffalo jerky. They would have made more but the salt was too expensive.

You remember those pictures of buffalo skulls piled so high they can’t fit them all in the frame, and then you wonder if that trading post was where the truck stop is now.

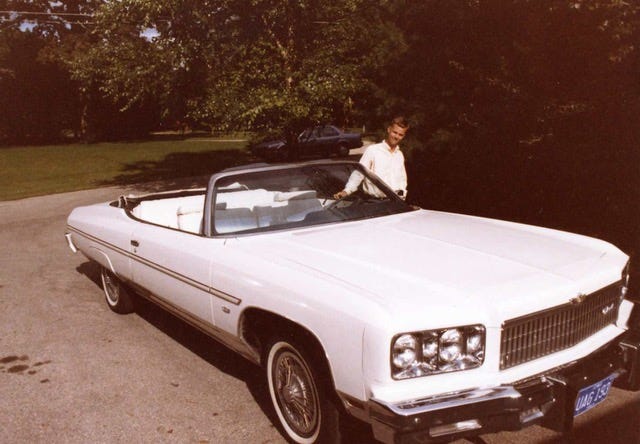

Rolling through Oklahoma City yesterday, we spotted a dude cruising I-35 in a ‘74 or ‘75 Impala. TYMMCHN, declared the vanity plates, and I remembered my own ‘74 Chevy, the one that got me through college and law school. It was a time machine, too, especially when you put the top down and took the blue highways instead of the interstates, conjuring some Pat Boone variation of the stählerne Romantik and getting deliberately lost like some malaise-fighting dork from a Walker Percy novel. I guess I’m still at it, even if the car isn’t as cool, and the company is definitely better.

We didn’t have time to take the scenic route this trip, especially on the way up, determined to minimize the chances we would expose baby’s Midwestern grandparents to deadly infection from one of those roadside motels we normally overnight in. We went straight from here to there in a day, fourteen hours on an interstate that runs almost directly from our home to theirs, through a landscape that was still depopulated by quarantine. The frontage road convenience stores seemed imminently apocalyptic, many of them cleared of all but the essentials, and the emerging sectarian divisions between the masked and the unmasked became more pronounced the deeper you got into the heart of the heart of the country. At the Belle Plaine service area south of Wichita, the families picnicking on the sidewalk outside the shuttered concessions gave a glimpse into a world of Midwestern refugees, under the tollway-funded frescoes of the settlers who came before them, and the people they displaced.

On our way back yesterday through northern Oklahoma, I had another atemporal glimpse. Off to the right, where the interstate crossed over a big creek, I saw a dude fishing off the ruins of a much older bridge, standing there with rod and reel on a collapsed concrete platform. A hallucinatory vignette that looked like both past and future. At the next exit, I saw we were passing through the reservation of the Tonkawa, one of the main tribes that used to occupy the area where we live in Central Texas.

The town of Wichita gets its name from another one of the tribes that used to live in these parts. My friend Todd (who, back when he was a grad student and I was an undergrad, gave me pro tips on how to use old highways as temporal vectors) is an expert on the Wichita Indians, and I have been reading his book about them, learning how they thrived for centuries ranging across the long transitional zone where the Eastern forests meet the Great Plains. When I was walking the dogs through downtown Wichita Saturday night, a sign reminded me how the main street there follows the route of the Chisholm Trail—the same trail that used to cross the Colorado River near our house in Austin. I had long known I-35 follows the approximate course of the Chisholm Trail from South Texas to where it picks up the Santa Fe Trail southwest of Kansas City. It was only this weekend that I realized that line I-35 follows is the one charted by the Wichitas, a trackway through liminal space.

I have driven past those signs for El Dorado dozens of times over the past two decades. It’s the hometown of my friend and fellow Austin fabulist Brad Denton, a town of flareoffs and drowned forest. On the way back yesterday I learned Coronado actually came through here on these same routes, in 1541, looking for lost cities of gold.

But on the way up, headed down the Kansas Turnpike toward its terminus in Eisenhower’s hometown of Topeka, that song from 1974 came up in the mix, and I got to thinking how the interstate highways are the most successfully imported of the Nazi technologies we captured at the end of World War Two. A way to use the natural contours and beauty of the land as the means to control it.

Vor uns liegt ein weites Tal

Die Sonne scheint mit Glitzerstrahl

Heimat

Our destination was a house full of German landscape paintings, some by my great grandfather, some by my great aunt (who later became known for her portraits of Stalin), and some by my late brother. My parents bought their piece of American landscape when they were the age I am now, and have spent the decades since then slowly restoring it, using little more than time and fire to bring an oak savannah back to something very close to the ecosystem that must have been here before the American farmers arrived.

As someone who spends much of his time exploring urban woods, it is always good to get a reminder of what a genuinely healthy forest feels like. I will confess that it is not as exciting for me to explore woods that harbor neither venomous reptiles nor abandoned muscle cars. But especially when in the company of an expert guide like my mother, whose personal vision has driven this unusual project, making a landscape of real wonder out of run-down ranch land too crummy to farm, you get a sense of the incredible bounty that can be brought back to the ecologies we have mostly destroyed. We could certainly see the wonder in our daughter’s face, as she soaked it all in from her perch atop our shoulders.

There is no entertainment up there beyond what nature and the company of family and friends provides (and, full disclosure, Wheel of Fortune—nothing like seeing a one-year-old who rarely sees TV suddenly mesmerized by the ageless cathode ray charisma of Pat Sajak). We ate from the land—venison taken from those woods, wild leeks and stinging nettles my mother foraged the same morning, fresh asparagus from the perennial plants in the garden. The cell networks finally seem to be reaching that little hole in reality, just in time for me to stop giving a shit what is coming in through my feed.

Thursday night I took the dogs out before bed. The sky was overcast, with a new moon, producing the blackest night I think I have ever experienced. Off to the west you could hear the cacophony of spring life in the wetland down by the creek, frogs and geese and bugs louder than when we can hear the music festivals upriver here in Austin. In the morning, the leftovers of successful predators could be found right at the perimeter of the house—the severed foot of a faun, little bits of bloodied bone, the fur from a ravaged warren. Farther down the woodland trail that once was a road, and maybe an Indian trail before that, I found the skull of a stag buried in the tall grass, relic of winter.

Growing up in the “Heartland,” you are surrounded by green, but rarely experience the authentically wild. I remember the trips we would take on Memorial Day when I was little, driving west out of Des Moines on the old highways to Guthrie County, where my father’s ancestors had settled in the 1840s, publishing small town newspapers. We would visit the graves of dead relatives who had fought for the Union, in cemeteries surrounded by newly planted fields that looked just like those Grant Wood paintings.

The Midwest is a landscape almost entirely subjugated to agricultural production, endless fields of genetically-modified corn and beans planted in chemically altered fields, a realm in which crows are the only birds that seem to really thrive. That landscape can't even sustain small-scale family farmers anymore, certainly not the way it did when my great-great-grandparents emigrated from Ohio, and in pockets like the stretch of South Central Iowa where we were, where the farming was never that good, you can see the intense poverty everywhere you look, as the once-proud small towns morph into ruined settlements that evidence the ecological and economic exhaustion that’s left after capital finds no more value left to take.

Now many unproductive old acreages up there are being turned into nature preserves, sometimes by hunters, sometimes by amateur naturalists. When they bought it in the ‘80s, my parents’ place was super scruffy, thick with species that didn’t really belong and yet devoid of real diversity. One of the first summers, I helped my dad try to clear bad brush with saws, a sweaty and Sisyphean undertaking. Controlled burns were what did the trick, making room over successive seasons for a majestic canopy of tall white oak and a thick carpet of plants underneath, many of them, and many of the insects that came with them, species long thought extinct in the state. And in the dirt below, recovered mycorrhizal networks. The ease with which the wild species come back reminds you how recent the damage to the land really was in this country, and how quickly it can be undone with just a bit of minimalist stewardship.

The Emerald City

Allen Ginsberg came to Wichita for a season in 1966, spending his Guggenheim money exploring the exotic mystery of how it was that so many Beat poets could come from a place that also produced so many John Birchers. I drove through Wichita many times before I ever got off the bypass to properly check it out. I think it was the trip some years ago when my son and I had a close encounter with a next-generation stealth aircraft landing just over our heads that I got sufficiently curious to explore on the other side of the toll plaza, past the motels.

Like the land around it, downtown Wichita is a weirdly atemporal place. Very few of the buildings appear to have been constructed after 1979, and something about the climate makes them all look new. The Arkansas River cuts through the middle of town, with a utopian little greenbelt, bringing waters flowing down out of the eastern side of the Rockies then in slow meanders across the plains. It’s a river I saw once closer to its source, stopping for lunch in a Colorado hippie town that seemed to be from a song John Denver would have written if he were cooler. But the light is different in Wichita, the way it’s different in Marfa, the kind of light that alters reality just enough.

The term Wichita Vortex may have been invented by Ginsberg, or he may have stolen it from a meteorologist, but when you visit that town in the crepuscular hour you know it describes something real. Something the Indians after whom the place is named must have known, about this crossroads at the heart of their expansive range. The way the land and the rivers and the weather let you hack your experience of time. You can feel it in the morning wind, a wind that has been building up across half a continent, reminding you of the ease with which the environment can erase our illusory permanence. And as you load the car to head back home, you can almost imagine a future in which those wild trajectories across the continent are liberated from our dominion.

For more on Ginsberg’s sojourn in the Wichita Vortex, check out this documentary from local PBS affiliate KTPS:

For more on oak savanna restoration, check out the Southern Iowa Oak Savanna Alliance and the blog of Timberhill Oak Savanna.

And for more on the Indians of the Southern Plains, check out the books on the subject by my friend F. Todd Smith, Professor of History at the University of North Texas—The Wichita Indians: Traders of Texas and the Southern Plains, 1540-1845, and From Dominance to Disappearance: The Indians of Texas and the Near Southwest, 1786-1859.

Did you know one of the popular names for the Baltimore Oriole is “hangnest”? The things you learn when you show your kid your own childhood books at Grandma’s house.

Have a great week.

I really enjoyed this "ecological and economic exhaustion that’s left after capital finds no more value left to take." Well said.

I am a dental friend of your father's. I grew up traveling the country you wrote about when I traveled from my home in Independence, MO to college in Tulsa, OK. Brought back pleasant memories of looking out car windows at the scenes you describe.